Chapter Twelve

Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee

Learning Objectives

After completing this chapter, the reader will be able to

• Describe the pharmacy and therapeutics (P&T) committee.

• Define the functions of the P&T committee.

• Describe attributes and structure of a P&T committee likely to promote its ability to function successfully.

• Describe where and how the P&T committee fits into the organizational structure of a health care institution or other groups.

• Describe how the pharmacy department participates in P&T committee activities.

• Describe and explain the concepts of drug formularies and drug formulary systems, and how pharmacy participates in their establishment and maintenance.

• Describe how P&T committee activities contribute to the quality improvement of medication use.

• Describe how to develop policies and procedures for the process of medication use.

![]()

Key Concept

Introduction

When considering how a pharmacist can have an impact on a patient’s drug therapy, it is common to consider the individual practitioner dealing with a specific patient or, perhaps, a small group of patients. Certainly the clinician can have a deep impact this way, but it does have the disadvantage of dealing with a very limited number of patients. In order for pharmacists to efficiently impact a population of patients, a different approach is necessary. Fortunately, pharmacists have the opportunity to participate in the activities of ![]() a P&T committee or its equivalent, which generally oversees all aspects of medication use in an institution. Physicians and pharmacists have collaborated to implement cost-effective prescribing practices and assess clinical outcomes through educational initiatives, administrative programs to restrict ordering practices, use of formularies and prescribing guidelines, and financial incentives.1 There are data to show that P&T committee actions are useful.2,3

a P&T committee or its equivalent, which generally oversees all aspects of medication use in an institution. Physicians and pharmacists have collaborated to implement cost-effective prescribing practices and assess clinical outcomes through educational initiatives, administrative programs to restrict ordering practices, use of formularies and prescribing guidelines, and financial incentives.1 There are data to show that P&T committee actions are useful.2,3

Before proceeding, it must be stated that while this chapter deals with the P&T committee, which is usually the group responsible for overseeing all aspects of drug therapy in an institution, there is sometimes a similar body referred to as the formulary committee. This latter group deals strictly with determining which drugs are carried within an institution or organization, whereas the P&T committee has numerous other tasks, covering all aspects of drug therapy (e.g., adverse drug reaction [ADR]/medication error monitoring, quality assurance, policy and procedure approval), although the exact group of functions may vary from place to place.4 Some institutions use a formulary committee, since other bodies may perform the additional P&T committee tasks described later in this chapter. Also, some health care groups may use both committees, with one body addressing the issues for the group as a whole, while the other is located separately at various institutions to address issues specific to that location (e.g., only one institution in the group has an oncology unit, therefore, the committee for that individual institution will consider specific antineoplastic agents that are not of much use for the rest of the group). In this chapter, anything discussed regarding which drugs are available within an institution or group applies to both bodies, whereas all other items are for the P&T committee only.

It should be noted that while P&T committees have normally been associated with institutional pharmacy, other organizations have increasingly used P&T-type committees in an attempt to improve drug therapy while lowering costs. Some places where such committees are seen include managed care organizations (MCOs),5 insurance companies, pharmacy benefit management (PBM) companies, unions, employers,6 state Medicaid boards, state departments of public institutions,7 Medicare,8 long-term care facilities,9 ambulatory clinics,10 and even community pharmacies.11 Much of this chapter will use examples from institutional pharmacy and managed care, simply because much of the published literature deals with those areas of practice and it is the most likely setting in which a pharmacist will be directly involved in P&T committee activities. However, the concepts covered are applicable to any P&T-type committee and comply with recommendations of the American Medical Association (AMA),12,13 the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP),14 The Joint Commission (formerly the Joint Commission for the Accreditation of Health Care Organizations) (TJC),15 and the Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy (AMCP).16

The role of the P&T committee has been continuously expanded over the years and now encompasses a great number of functions and activities that cover all aspects of overseeing drug therapy. As some of these are of sufficient size and importance, they are covered separately in other chapters (e.g., drug monographs and quality assurance). In addition, there are a number of areas (e.g., investigational drugs) in which P&T committees play a secondary role, and these too are covered in other chapters. This chapter will serve to provide a base to tie together discussion of all of these areas and a number of smaller functions or activities that will be covered as a portion of this chapter. The information is appropriate both for those just learning about the concepts and also for those individuals who are involved with P&T committee activities.

Organizational Background

The concept of a P&T committee represents a unique niche within the structure of a hospital or hospital system. The current role of a hospital in Western countries17 began about 200 years ago, at a time when very few efficacious medications were available, although drug formularies had been developed during the Revolutionary War to list the drugs available.18 It has also been noted that a drug formulary was developed for all municipal hospitals in New York City at Bellevue Hospital in 1868.19 Drug formularies were required for participation in the Medicare program in 1965.20 The original hospital was a place to receive basic health care when a person had no extended family to provide the basic needs of good health. After infection control became a recognized concept and anesthesia for surgery evolved around 1900, the value of the modern hospital progressively became a recognized need for all segments of society. The origins for standards of how a hospital functioned subsequently developed during the first half of the twentieth century. This began with the early efforts of the American College of Surgeons in the United States (U.S.) to develop the first accreditation standards for hospitals. Later, the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Hospitals (JCAH), now known as TJC, evolved to centralize the basic requirements for the functional character of a U.S. hospital. The concept of the P&T committee originated and evolved to help hospitals meet various standards regarding drug therapy. The first P&T committee was formed at Bellevue Hospital in New York City in the mid-1930s.18,21 While it dealt with true compounding formulas, it was originally founded to ensure quality and efficacy of those products, which is still a portion of the functions of P&T committees.

In keeping with the social origins of the hospital, the legally sanctioned or licensed privilege of being a professional health care provider evolved.17 Both the physician and pharmacist were considered unique for the needs of society. Minimum standards evolved, including the accreditation of their training as a basis for being licensed. Originally, physicians and pharmacists functioned primarily as independent professionals. The nature of a physician’s independence was legally defined to further support their obligations to a patient. Many states in the United States legally prohibited a physician from being employed by a corporation. Eventually, these laws were all repealed, but they had the effect of creating the basis for a medical staff as being a separate legal entity within a hospital. The medical staff reflected the legally evolving traditions of a physician, and indirectly the pharmacist, as being independent professionals committed only to the care of a patient without unnecessary outside influences. This evolution has had a major impact on the organizational structure of hospitals.

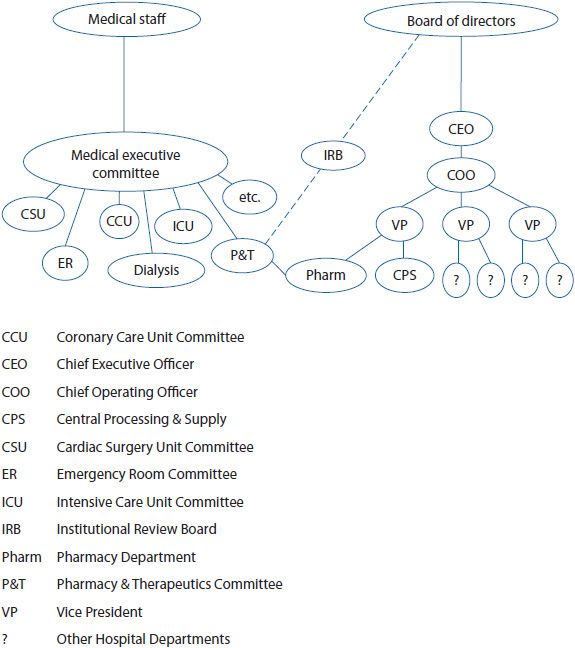

A typical hospital organization is shown in Figure 12–1. The board of directors divides the functions of its organization into two entities. First, the administration of the hospital operates as a typical business with a chief executive officer, chief operating officer, and so forth. Second, the board of directors authorizes that a medical staff be formed that reports separately to the board of directors. While the medical staff as a whole is ultimately in charge of all clinical aspects of care in the hospital, in most institutions this is unworkable without an administrative structure of some kind. Therefore, the medical staff may elect officers and either elect or appoint somebody to oversee all aspects of patient care. In this example, the term medical executive committee is used for that body, although the name and exact function may vary. The medical staff functions to certify the credentials of its members, establish their scope of practice where appropriate, monitor the quality of health care provided by its members, and maintain the means to collaborate with the administration of the hospital.

Figure 12–1. Hospital organization.

In modern medicine, there are so many clinical areas to consider that it is unrealistic for one committee to adequately oversee all aspects of patient care, except in very small institutions. For this reason, various subcommittees of the medical executive committee are usually necessary, as can be seen in Figure 12–1. As a means to coordinate the needs of the medical staff and the operation of the hospital pharmacy, the modern P&T committee developed. From the traditions established by TJC and ASHP, the P&T committee developed as a function of the medical staff’s responsibilities. This committee or related committees may have other names, such as the drug and therapeutics committee in other countries,22,23 but the functions are the same. While the P&T committee has been referred to in TJC accreditation standards in the past, it is no longer specifically required and may be replaced by some other committee or body,15,24,25 although the P&T committee concept is supported by many national and professional organizations.26 Given the continuing growth in the number, complexity, and expense of medications, both the importance and number of functions of the P&T committee have continued to increase. Policy and procedures to set up a P&T committee are described in Appendix 12–1, but the following will serve as a general description of P&T committees and their actions.

In some cases, the P&T committee may be part of a corporation of hospitals and medical centers, rather than just being for a specific institution. While the philosophy of operating one P&T committee within this corporate structure seems reasonable, this is not often accomplished without problems and decentralization of these efforts may be better.27 Different patient populations, medication needs, cross hospital physician participation, meeting time, length and location of meetings, and differing clinical cultures within a specific institution are examples of barriers that may be present. The P&T model may need to be revised to work with these challenges.28–33

Although it is easy to assume from its name that the P&T committee is organizationally a part of the pharmacy department, such is not the case, as was mentioned above. Instead, it is usually a medical staff entity and, perhaps, only one or two pharmacists may actually be members of the committee (possibly ex officio members without voting privileges). Commonly, the pharmacy director or clinical coordinator, serving as the committee’s secretary (e.g., taking minutes, collating, and arranging the agenda), may be the sole official pharmacy representative. Other pharmacists may also attend to act as consultants to the committee, often having great impact on the committee’s decisions, even if they cannot officially vote. Fortunately, in larger hospitals, it appears that more pharmacists are now becoming full members of the P&T committee.34

Typically, the voting members of an institutional P&T committee are limited to members of the medical staff, although there may be a few voting or nonvoting members from other groups, including pharmacy. Membership is mostly physicians (preferably a wide variety of physicians from various areas of practice), but usually includes at least one pharmacist and often members from other areas of the hospital (e.g., nursing, administration, radiology, respiratory therapy, dietary, quality assurance, medical records, laboratory, and risk management).35 A pharmacoeconomist also can be extremely helpful. There have also been recommendations to include other individuals, such as a medical ethicist or community pharmacist.36 It may be best to try to keep down the number of physician members to encourage a smaller group to participate more fully, while taking care of addressing the wide variety of issues by calling in physicians to consult with the committee on an as needed basis.37 In some cases, the pharmacy department is asked to recommend physicians for the committee. If possible, pharmacy should suggest physicians who are noted for their commitment to rational drug therapy.38 As an example, the U.S. Department of Defense has procedures for appointment of members, including nonphysician members, of the P&T committee. The procedures are available on the Internet.39 Also, efforts should be made to ensure that the physician chosen to be chairman of the committee is an advocate of the pharmacy department. It is possible for the medical executive committee of the medical staff to pass a resolution to approve a policy broadening the voting members of the P&T committee (e.g., director of pharmacy or hospital vice president) or delegating the functions of the P&T committee to the hospital. In this latter arrangement, the medical staff would reserve the right to terminate the policy if the P&T committee fails to support the needs of the medical staff. If the P&T committee is a hospital committee, rather than medical staff committee, a pharmacist or nurse might more easily obtain voting privileges, given appropriate physician quorum requirements in the authorizing policy.

The P&T committee of MCOs and government bodies often have similar membership to that in institutional committees; however, there may need to be a requirement for at least some of the members to be independent practitioners and retail pharmacists (i.e., having no financial ties to the organization or group that sponsors the P&T committee).35,40,41 In accordance with the 2003 Medication Modernization Act, the use of formularies is an essential component to the PBM.35

Once the general organizational setting of the P&T committee has been determined, the operating policy of the P&T committee requires careful attention to two key issues. The first key issue is obvious—to whom does the P&T committee report and to what degree can the decisions of the P&T committee be overturned by another segment of the organization? It is important to point out that the P&T committee may act only as an advisory body to the medical executive committee. Decisions of the P&T committee may not be considered final (and, therefore, not be implemented) until they are reviewed and approved by the medical executive committee. In this situation, a report is forwarded from the P&T committee after each meeting to the medical executive committee. In addition, an annual report of the P&T committee may be prepared for both internal review and review by the medical executive committee. This annual report is time consuming in preparation, but is a very important means of tracking P&T activities and action over time.

The second issue is that the P&T committee will likely be successful based on the leadership qualities of its members and the chairperson. The role of the chairperson includes developing the respect and involvement of all members of the committee.

PHARMACY BENEFIT MANAGEMENT (PBM) P&T COMMITTEE ORIGIN

The origin of the PBM organizations dates back to the late 1960s. Their primary focus was on claims administration for insurance companies. Later, it became a challenge for the insurance companies to efficiently manage the increase in drug coverage in the private sector when the prescription volume was high and the cost per claim was low.42 The plastic drug benefit card began in the 1970s and changed the way many prescriptions were bought and paid for by the insurance company and employee. From then on, any employee with an ID card, using a pharmacy network, only had a small copayment.42 In addition, administrative costs for the third-party payer, whether it is the insurance company, health plan, or employer, were reduced, with the PBM creating pharmacy networks and mail service benefits. Pharmacy networks are a group of pharmacies that are under contract with the insurance company, health plan, and/or their contracted PBM partner to promote prescription services at a negotiated discounted fee.43 Mail service is a program offered by the PBM, whereby pharmaceutical agents, both prescription and nonprescription, are offered through the mail.43

In the late 1980s, the introduction of real-time electronic claims processing began. Not only was there two-way communication between the pharmacy and the PBM for claim processing, but also for clinical information. In the 1990s, the PBMs moved toward a greater emphasis on patient health by offering a variety of new services in addition to the claims processing. Since 2000, there has been an emphasis on consumer behavior modification, enhanced patient interventions, physician connectivity, clinical consulting, disease management, and retrospective drug utilization review (DUR; see Chapter 14 for further information) to name a few.42

One of the key functions of a PBM is to design, implement, and administer outpatient drug benefit programs for employers, MCOs, and other third-party payers. PBMs manage prescription drug benefits separate from other health care services (i.e., physician and hospital services).43 Determining which medications are most cost-effective, without compromising patient care, is one of the key elements for controlling the cost of a prescription drug benefit.6,44 PBMs accomplish this by developing drug formularies.6 Formularies define what medications are covered (i.e., paid for) and provide the main component of the pharmacy benefit. Specific PBM drug payment and management activities occur within this formulary structure, such as therapeutic interchange and disease management programs. Eighty to one hundred percent of PBM-covered lives receive some type of formulary management service.6,43 The use of drug formularies is in flux due to the advantages and disadvantages identified over the last decade or so; however, they are likely to be continued for at least the foreseeable future, particularly due to the Medicare drug formulary requirements.45

Development and maintenance of drug formularies for third-party payers is an ongoing process. The formulary must be continuously updated to keep pace with new drugs, therapies, prices, recent clinical research, changes in medical practice, evidence-based treatment guidelines, and updated Food and Drug Administration (FDA) information.46 PBMs use a panel of experts called the P&T committee to develop and manage their drug formularies. Many times individuals with special clinical expertise are consulted when considering medications within a specific therapeutic class.46 Meetings are usually held on a quarterly basis, and not only are drug formulary recommendations made, but this group also provides input into other clinical areas, such as development of disease management programs.6,42,43,45,46

Many PBMs establish their own P&T committee to evaluate the efficacy, safety, uniqueness, cost of therapeutic equivalent drugs, and other appropriate criteria. In addition, PBMs work with the health plan, employer, or insurance company P&T committee to develop drug formularies using the same evaluation process. In either case, if the P&T committee determines that one drug provides a clear medical benefit over the other, therapeutically equivalent drugs in that same therapeutic category, the drug is usually added to the formulary.6 However, if there are drugs in the same therapeutic category that have very similar efficacy and safety profiles and no unique properties that would make it a better drug, then the net cost becomes a deciding factor as to which drug should be added to the formulary.6 There has been some discussion as to whether drug costs are weighted too heavily, while drug efficacy and other clinical information is weighted too lightly when it comes to drug formulary decisions.42,43 The committee leadership needs to recognize the potential for conflicts of interest between efficacy and economic interests of the PBM and to establish collaboration as the basis for resolving conflicts that arise.

Me-too drugs are drugs that are structurally very similar to an already known drug that has only minor differences. Many drugs come in two versions: an L-isomer (left) and an R-isomer (right). An example of a me-too drug is esomeprazole (Nexium®), the L-isomer of omeprazole (Prilosec®, the R- and L-isomers). Both drugs are used to treat gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). When a comparative analysis was conducted looking at drugs approved for marketing between January 2007 and July 2008, those that had a different chemical entity and a separate mechanism of action accounted for 69%; however, they offered no clinical improvement over those already on the market. Forty-four percent offered some type of new convenience, but only 13% offered greater efficacy.47

In the case of a health plan, employer, or insurance company’s own P&T committee, the drug formulary recommendations made by the PBM P&T committee are presented and reviewed by the organization’s P&T committee. The PBM recommendations regarding drug formulary recommendations can be either accepted or denied by the organization’s P&T committee and the organization’s own decision made regarding formulary inclusion.

Pharmacy Support of the P&T Committee

![]() Although it is not uncommon for pharmacists to downplay or misunderstand the importance of P&T committee support in comparison to other clinical activities, such support is vital for pharmacy to impact patient care. P&T committee support and participation can have far-reaching effects on the overall quality of drug therapy in an institution and must be given a great deal of attention, since the benefits of its function serves to build collaboration, transparency, and trust among the institutional divisions of authority for drug therapy within health care. While such attention is time consuming,48 it can be of value to the pharmacy since this is an opportunity to present recommendations to a decision- making body and P&T committees often accept pharmacy recommendations49,50; therefore, pharmacy departments can have a great and far-reaching impact on drug therapy through this mechanism.

Although it is not uncommon for pharmacists to downplay or misunderstand the importance of P&T committee support in comparison to other clinical activities, such support is vital for pharmacy to impact patient care. P&T committee support and participation can have far-reaching effects on the overall quality of drug therapy in an institution and must be given a great deal of attention, since the benefits of its function serves to build collaboration, transparency, and trust among the institutional divisions of authority for drug therapy within health care. While such attention is time consuming,48 it can be of value to the pharmacy since this is an opportunity to present recommendations to a decision- making body and P&T committees often accept pharmacy recommendations49,50; therefore, pharmacy departments can have a great and far-reaching impact on drug therapy through this mechanism.

Some pharmacists who participate in P&T committee activities feel they are serving their function by just providing information requested by physicians and considering drugs for formulary approval only following physician requests. This can rapidly deteriorate into crisis management, where the pharmacy department reacts to problems, fighting each fire as it occurs. It is much better for a pharmacy to be proactive,51,52 seeking to address issues (e.g., changes in drugs carried on the formulary, new policies and procedures, quality assurance activities, and so forth) before they become problems. TJC accreditation requirements include annual evaluation of all drugs and/or drug classes.15 Through prospective actions with the P&T committee it is possible for the pharmacy to get physician support for their clinical activities.

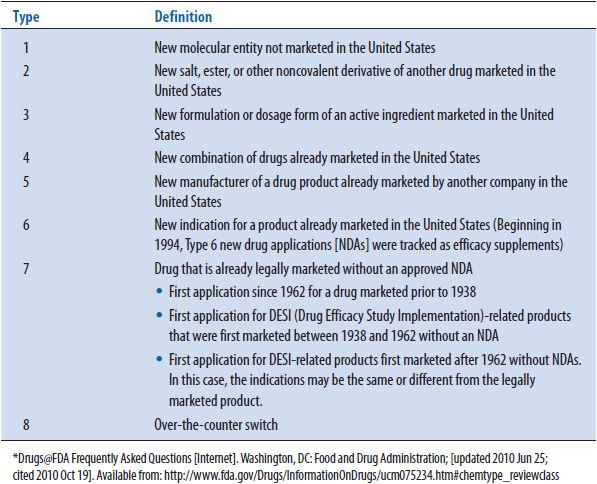

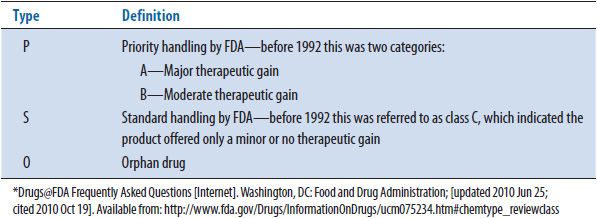

In the specific instance of P&T committee support, one or more pharmacists must be identified to conduct the necessary planning. This may consist of a pharmacy-based steering committee and might include administrators, purchasing agents, or clinicians, and, particularly, drug information specialists. These people must develop and regularly evaluate data sources to anticipate physicians’ needs53 (see Table 12–1). For example, it is necessary to assess what drugs have been recently FDA approved in order to identify drugs for possible formulary inclusion. FDA approval often occurs about 3 months before commercial availability and is published on the FDA Web site (http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/drugsatfda/index.cfm). Therefore, there is time for the drug to be considered for formulary addition before the first orders arrive from the nursing units, which necessitates a review of some sort under TJC standards.15 In a case where it is not possible to consider a drug before it is commercially available, it has been suggested by some that drugs rated P (priority) by the FDA be made available to physicians until the drug can be fully considered (the FDA classification codes are found in Tables 12–2 and 12–3, with the priority versus standard explanation found in Table 12–3).54 This latter procedure may be effective, but considering the drug before commercial availability is preferable, because if the ultimate P&T committee decision is to leave the drug off the drug formulary, there may be difficulties in helping physicians stop the use of the product. It is also a good idea to track older drugs. For example, the use of nonformulary drugs may be tracked within the hospital (Note: a nonformulary drug may be a product that has not been approved for use within an institution, but may also be a drug that has been approved for use, but has been prescribed in a particular situation for a use other than what was approved by the P&T committee when it was added to the drug formulary).55–57 If patterns of increased use are noted, it is best to identify a reason for that use. If the use is inappropriate, the physician(s) should be contacted and given information about alternative formulary agents. In some cases, new information may be available showing a new advantage or use for an old agent, which can lead to its reconsideration for formulary adoption. Related to this is the necessity to regularly consider the material being promoted by the drug company representatives. It is worth mentioning that some hospitals will restrict drug representative access to the institution or restrict the drugs that may be promoted by those representatives to only items approved for use in the hospital in order to prevent this problem (see Chapter 24 for further information). There may also be new indications or other information that will increase demand for nonformulary items. If there are sufficient changes noted in the use(s) of a particular class of drugs, it is useful to review the class as a whole to decide which drug(s) are to be retained on the formulary. TJC now requires annual review of all medications,10–15 which is useful because there may be new information (e.g., labeling changes or safety in terms of postmarketing surveillance) not otherwise noted that necessitates changes in formulary items in a particular class, both additions and deletions. However, these situations that have been noted above may necessitate moving up the review. Other items, such as trends in reported ADRs in the institution or published data for new products with little information in the literature on first approval may also be useful in determining products for P&T committee consideration or reconsideration.58 Although there must be a mechanism by which physicians can request that drugs be added to the formulary, all of the above methods and others can help the pharmacy anticipate physician needs, allowing time for information gathering, evaluation of products, and P&T committee consideration before the need becomes too urgent to permit proper consideration.

TABLE 12–1. AREAS WHERE PHARMACISTS SHOULD BE SUPPORTING A PHARMACY AND THERAPEUTICS COMMITTEE

TABLE 12–2. FDA CLASSIFICATION BY CHEMICAL TYPE*

TABLE 12–3. FDA CLASSIFICATIONS BY THERAPEUTIC POTENTIAL*

To guide the clinician into considering the logic of requesting the addition of items to the drug formulary, a specific request form may be useful. Items that a physician may be required to fill out or attach to the form can be seen listed in Table 12–4.59 An example form is seen in Appendix 12–2.

TABLE 12–4. ITEMS THAT MAY BE ON A REQUEST FOR FORMULARY CONSIDERATION FORM

The P&T committee should be kept advised by the above-mentioned pharmacy-based steering committee of future plans, so that it can be aware that a rational planning process is governing its agenda. Also, it is a good idea for one or more representative(s) of this steering committee to meet with the pharmacy director, chairman of the P&T committee, and a representative of the hospital administration on a regular basis to assist with planning and ensure their concerns are addressed. This meeting could be held shortly before the P&T committee actually meets to present preliminary formulary evaluations, DUE material, and policy and procedure documents for an initial review, allowing modifications addressing physician and administration concerns to be made before formal committee review and action. During this meeting, plans for future months can be made or adjusted as the circumstances dictate. Other appropriate physicians or groups should also be consulted in order to ensure that their concerns are addressed. For example, if changes to the cephalosporins carried on the drug formulary or their permitted uses (e.g., restrictions to particular uses or prescribing groups) are considered, the infectious disease specialists should be contacted to provide input. (Note: This does not necessarily mean that recommendations are changed to account for physician preferences, but that their preferences and concerns are specifically addressed in the evaluation.)

Regarding quality assurance activities, the pharmacy department should obtain data to guide the selection of upcoming quality assurance programs. This will be covered in greater detail in Chapter 14.

The pharmacy should also investigate which medications need specific policies and procedures developed to guide their use and monitoring. This may be done when the drug is first being evaluated for formulary addition or later if problems (e.g., increased ADR reports, medication errors, and overuse) are noted. For example, concerns about a new thrombolytic agent leading to increased morbidity and mortality through improper use might prompt the P&T committee to approve specific protocols for the use of the agent. Policy and procedure documents are covered later in the chapter. Information on preparing policies and procedures can be found in Chapter 18.

Finally, it is extremely important for the P&T committee to make sure that physicians are informed about the actions taken. Often the pharmacy is heavily involved in providing this information to physicians. While a great deal of effort is placed on communication within the committee itself, it is also necessary to keep the entire medical staff informed. This may be accomplished through medical department meeting presentations, newsletters and Web sites (refer to Chapter 9), or other mechanisms.

AD HOC COMMITTEES

![]() A P&T committee may find it necessary to create ad hoc committees to address various issues, depending on their complexity and size. Some of the common committees are discussed below. Institutions may or may not use these committees (sometimes referred to as subcommittees) and their exact use varies from place to place, depending on their needs or desires.4

A P&T committee may find it necessary to create ad hoc committees to address various issues, depending on their complexity and size. Some of the common committees are discussed below. Institutions may or may not use these committees (sometimes referred to as subcommittees) and their exact use varies from place to place, depending on their needs or desires.4

Adverse Reactions

A comprehensive ADR monitoring and reporting program is an essential component of the P&T committee (see Chapter 15 for further information about ADRs and how they are handled). A subcommittee may be helpful to review the entire ADR data for trends and any necessary actions that need to be taken. The P&T committee will usually report the ADR data on a monthly or quarterly basis. Following approval of this report, the P&T committee is responsible for the dissemination of information to the medical staff and other health professionals in the institution. This includes recommending processes to cut the rate of preventable ADRs. This subcommittee may be combined with the medication errors subcommittee.15,60

Anticoagulation

The anticoagulation subcommittee is responsible for policies and procedures to maintain compliance with TJC Goal 3E, now called the TJC National Patient Safety Goal 03.05.01.15 This goal is to reduce the likelihood of patient harm associated with anticoagulation therapy. The subcommittee can also participate in improvement processes to maintain standards with quality organizations such as the National Quality Forum (NQF), and the Surgical Care Improvement Project (SCIP). Standard orders and policies to follow evidence-based guidelines of the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) are also developed by this subcommittee. Pharmacists have an important role on this committee. Most hospitals have pharmacists dedicated to anticoagulation monitoring and education.

Antimicrobials/Infectious Disease

Antibiotics can represent the largest category of formulary medications.61 Frequent category review and revision is necessary and complex.62 Cunha has defined five factors to consider when reviewing antimicrobial agents for formulary inclusion: microbiologic activity,63 pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics profiles,64 resistance patterns,65,66 adverse effects,67 and cost to the institution.68 The P&T committee or a subcommittee of the P&T may be responsible for developing appropriate antibiotic selection and use in both inpatient and outpatient settings.69,70 Some institutions may rely on input from the infection control committee regarding antibiotic formulary management and appropriate utilization. Multidisciplinary antibiotic use committees have limited inappropriate prescribing of antimicrobials and increased the medical staff’s knowledge on appropriate antibiotic use.68,71,72

The main purpose of the antimicrobial/infectious disease subcommittee is to promote antimicrobial stewardship to ensure cost-effective therapy and improve patient outcomes. Antimicrobial stewardship promotes and optimizes antimicrobial therapy consistent with the hospital’s/health system’s antibiograms. Guideline development and education is provided to the medical staff as well as to other health care professionals. The subcommittee is also involved in the enforcement of formulary agent use, substitution policies, and restrictions for antibiotics. In addition, review and feedback on prescribing patterns is provided to the medical staff regarding antibiotic therapy.73–75 Use of P&T formulary and policy decisions has been shown to be successful in controlling antimicrobial use in hospitals.76,77

Medication Safety

A medication safety committee (sometimes called safety committee or medication misadventure subcommittee) should be multidisciplinary in nature. This subcommittee will review medication misadventures and medication errors that occur within the institution or health care system. They may also review adverse drug reactions (instead of an adverse reaction committee), drug–drug interactions, drug dispensing processes, medication errors (see Chapter 16 for more information), look-alike/sound-alike medications, and communication errors. It may also be appropriate for them to review protocols to improve medication safety, such as the settings for intravenous fluid pumps. A report will commonly be presented to the P&T committee on a quarterly or semiannual basis. Following approval of this report, the P&T committee is responsible for the dissemination of information to the medical staff and other health professionals in the institution. This includes recommending processes to cut the rate of preventable medication safety issues. In some places, a medication error reduction plan (MERP) is prepared to identify process improvements that have been made and those that are planned. When evaluating drug cost strategies, patient safety should always be a priority.78 The 2013 Joint Commission Accreditation Process Guide for Hospitals addresses the potential for adverse drug events.15 Also, as will be explained in the next chapter, patient safety will be evaluated whenever a product is considered for formulary addition.

Medical Devices

The P&T committee or a subcommittee may be responsible for the approval of some medical devices within an institution. This subcommittee is often multidisciplinary and is given the opportunity to review medical devices before purchases are made or contracts are signed. The committee is also responsible for reviewing the safety information associated with these devices because adverse medical device events are an important patient safety issue. Devices that contain medications, such as topical hemostats that contain thrombin, may also be reviewed by the committee or by the transfusion service committee described below.

Nutrition

As nutrition of the hospitalized patient evolved and became more complex, the role of the pharmacist on a nutrition support team became more justified. Their role started out improving the ordering process for parenteral nutrition, and communicating these changes to the pharmacy staff for proper preparation. Today, pharmacists on the nutritional team assist in the clinical management of parenteral nutrition patients, parenteral nutrition research, and continual involvement with improving the safety of parenteral nutrition use.79 TJC, in their National Patient Safety Goals (NPSG), once addressed the safe use of parenteral nutrition feeding solutions,80 but even though that has been removed, one of the responsibilities of the P&T committee is to oversee and approve the components of the parenteral nutrition solutions.

Quality Assurance of Medication Use

A subcommittee of the P&T committee may be placed in charge of planning and overseeing the plan for quality assurance regarding drug therapy. Details about this activity are found in Chapter 14. This committee may develop criteria for a drug use evaluation, collect the data, interpret the data, and recommend acting when necessary regarding the appropriate use of medication.

Tranfusion Service Committee

Hospitals often have a transfusion service committee charged with reviewing the use of blood and blood derivative products. Many of these products overlap with medications and may also be classified as medications. Therefore, it is necessary for this type of committee to work with or, possibly, be combined with the P&T committee in order to oversee the proper use of such products.81

Many times departments or service lines (e.g., oncology, cardiology, psychiatry/mental health, radiology, anesthesiology, women’s health) are asked for input regarding the formulary management within their specialty area of practice.

P&T COMMITTEE MEETING

Before beginning the description of a typical P&T committee meeting, it is important to note that a smoothly functioning P&T committee has certain needs. The committee will need the support of its parent organization. A room for the meetings should be carefully selected (see Appendix 12–3). The agenda for the meeting should be prepared in advance by the committee’s secretary and sent to the members. Most often, as mentioned previously, an informal meeting of the supporting pharmacists and others is required between P&T committee meetings to plan the activities necessary to support the agenda. The chair of the committee may also attend such planning meetings to ensure that priority issues are addressed before the meeting. Formulary reviews represent a special concern when sending out an agenda, since they may trigger the outside influences of dedicated pharmaceutical marketing efforts if companies learn from committee members that their products or their competitor’s products are being evaluated. Efforts must be made to make sure the committee is not distracted by outside influences, such as the pharmaceutical industry and advertisements. This consideration should be reflected in the selection of members and it may be necessary to avoid sending out some materials ahead of time, to lessen the chance of them being obtained by pharmaceutical company representatives. Also, if it is possible to prevent pharmaceutical representatives from knowing the membership of the committee, many of these problems may be avoided. If materials are sent out, it may be found that sending minutes from the previous P&T committee meeting is not always appropriate, since it may be difficult to adequately describe the full basis of a decision in a set of minutes. As a result, the minutes might be open to inappropriate projection regarding the basis for the P&T committee decision process. Some institutions simply make the minutes a pure recording of the decisions, eliminating any information about the discussion to avoid this problem. A sample set of minutes is seen in Appendix 12–4. Along with sending an agenda to members, a reminder phone call, fax, and/or e-mail may be useful to facilitate attendance. Each P&T committee meeting will require extensive preparation by the pharmacists involved in its affairs. Specifically, management of the formulary requires extensive background research and the preparation of written reports for any addition or deletion. Similarly, quality-related functions require time-consuming review of patient records. Finally, the P&T committee functions will be peripherally related to other affairs of the parent organization, for example, the standard order set preparation by other segments of a hospital. This requires special attention in order to prevent the use of nonformulary products. These items will be discussed in greater detail in the next section. Finally, the chairperson should be skilled at guiding an efficient meeting (see Appendix 12–5). In respect of the time commitment for members, meetings should always start and end at the scheduled times.

P&T COMMITTEE FUNCTIONS

![]() Typically, P&T committee functions include determining what drugs are available, who can prescribe specific drugs, policies, and procedures regarding drug use (including pharmacy policies and procedures, clinical protocols, standard order sets, and clinical guidelines—see Chapter 7 for the latter), performance improvement as well as quality assurance activities (e.g., drug utilization review/drug usage evaluation/medication usage evaluation, as well as compliance surveillance—see Chapter 14), adverse drug reactions/medication errors (see Chapters 15 and 16), dealing with product shortages, and education in drug use.15,82,83 Many of those functions are related to quality assurance activities, because they are designed to improve the quality of drug therapy. Because the functions may improve drug therapy quality, they may actually provide some legal protection for an institution, as long as the reason for decisions is not strictly based on financial considerations.84 P&T committee functions can also include investigational drug studies; however, that is often delegated to the Institutional Review Board (IRB) that oversees all investigational activities in the hospital (see Chapter 17). In addition, some P&T committee functions may be delegated to subcommittees (e.g., quality assurance, antibiotic, and medication errors subcommittees)85; however, this can be cumbersome and is often avoided, except in larger institutions. P&T committees should recognize principles of epidemiology and pharmacoeconomics in the decision making whenever possible.86–88 A standardized safety assessment tool has been developed to evaluate potential formulary agents.89

Typically, P&T committee functions include determining what drugs are available, who can prescribe specific drugs, policies, and procedures regarding drug use (including pharmacy policies and procedures, clinical protocols, standard order sets, and clinical guidelines—see Chapter 7 for the latter), performance improvement as well as quality assurance activities (e.g., drug utilization review/drug usage evaluation/medication usage evaluation, as well as compliance surveillance—see Chapter 14), adverse drug reactions/medication errors (see Chapters 15 and 16), dealing with product shortages, and education in drug use.15,82,83 Many of those functions are related to quality assurance activities, because they are designed to improve the quality of drug therapy. Because the functions may improve drug therapy quality, they may actually provide some legal protection for an institution, as long as the reason for decisions is not strictly based on financial considerations.84 P&T committee functions can also include investigational drug studies; however, that is often delegated to the Institutional Review Board (IRB) that oversees all investigational activities in the hospital (see Chapter 17). In addition, some P&T committee functions may be delegated to subcommittees (e.g., quality assurance, antibiotic, and medication errors subcommittees)85; however, this can be cumbersome and is often avoided, except in larger institutions. P&T committees should recognize principles of epidemiology and pharmacoeconomics in the decision making whenever possible.86–88 A standardized safety assessment tool has been developed to evaluate potential formulary agents.89

According to TJC, the medical staff, pharmacy, nursing, administration, and others are to cooperate with each other in carrying out the previously mentioned functions.15 Although the medical staff normally takes overseeing drug therapy very seriously and expects to approve all activities of the P&T committee, it is common for the pharmacy department to do much of the preparation work for the committee. Although it is tempting to say the reason pharmacies are charged with all of the work is that they are the drug experts, which is usually true, it is probably more realistic that the reason is that pharmacists are paid to do this as part of their salary. Physicians usually do not obtain any direct monetary compensation for this committee’s work, although such compensation may be considered by an institution to encourage more physician participation.

Case Study 12–1

You are the clinical pharmacist assigned to be the Secretary of the pharmacy and therapeutics committee (P&T). You are asked to develop an agenda for each monthly meeting, prepare each agenda topic, present each agenda item in a presentation, take notes, and provide follow-up to the meeting.

• What steps do you need to take to prepare an agenda?

• What steps are needed to prepare a medication monograph, including the summary page?

• What methods are used to disseminate the information once approved by the committee?

![]()

FORMULARY MANAGEMENT

Drug Formulary

Wherever a drug formulary system is in place, there is usually a drug formulary published, as a hardcopy book and/or more commonly in electronic format (e.g., Web site, intranet, or other software). In its simplest form, the drug formulary contains a list of drugs that are available under that formulary system, which reflects the clinical judgment of the medical staff.90,91 This list will be arranged alphabetically and/or by therapeutic class (American Hospital Formulary Service [AHFS] classification usually), and usually contains information on the dosage forms, strengths, names (e.g., generic, trade, and chemical), and ingredients of combination products. Many drug formulary publications contain a great deal more material related to the drugs, including a summary of indications, side effects, dosing, use restrictions, and other clinical information.92 Formularies may also be referred to as preferred medication lists or preferred drug lists.18

A related term, the formulary system, can be thought of as a method for developing the list, and sometimes even as a philosophy.93 In theory, a well-designed drug formulary can guide clinicians to prescribe the safest and most effective agents for treating a particular medical problem, at the most reasonable cost.94–99 Some people argue that the formulary system itself does not work because it is not properly implemented and recommend replacing it with counterdetailing by pharmacists or computers at the time a prescription order is written (see Chapter 23 for further information).100 However, whether or not that is true has yet to be determined. The most well-known article indicating that formularies may ultimately result in higher patient costs was written by Horn and associates.101 While this may be one of the best articles on the topic and the author has defended criticism of the article,102 there are nevertheless various deficiencies in the study that make it uncertain whether it was truly the drug formulary or other factors that lead to increased costs.103–106 Horn and associates107 also published a similar study conducted in the ambulatory environment, which appears to have similar results and deficiencies. In the case of national drug formularies, there has been a positive108 effect on prescribing habits shown in Canada. A study of formulary use in the western Pacific region found that they are commonly used in hospital, but questioned their effectiveness, since in that area the products on the formulary are often not connected to treatment guidelines or the best evidence for treating disease.109 Further research is needed before a definite conclusion may be reached on the effectiveness of formulary management.110 For now, a well-constructed formulary is still believed to improve patient care while decreasing costs. It serves as a focus for building comprehensive drug therapy options.

The goal of the formulary system is to provide a decision-making process leading to the selection of medications necessary for the treatment of any disease states likely to be seen in that institution.95 In some cases, decisions for formulary addition can be made for entire groups of institutions, for example, the U.S. Veteran’s Administration has combined the formularies of all of its component parts.111 These formulary medications should be the most efficacious and cost-effective agents with the fewest side effects or drug interactions.15 Other factors should also be taken into consideration, such as the variety of dosage forms available for the medication, estimated use, convenience, dosing schedule, compliance, abuse potential, physician demand, ease of preparation, storage requirements, and risks.112 Economic factors should not be the sole basis for this evidence-based process.95 Typically, only two or, perhaps, three drugs from any drug class are added to the formulary. Some people would argue that only one agent is necessary from any class; however, some individuals will not respond and/or tolerate certain agents, so at least one secondary agent is usually desirable. Therapeutic redundancy must be minimized, however, by excluding superfluous or inferior preparations. This should improve the quality of prescribing and also lead to improved cost-effectiveness, both by eliminating less cost-effective agents that do not improve patient care and by assisting patients to become well faster. To analyze potentially conflicting literature and strength of recommendation, a grading system has been developed for review of potential formulary additions.113

Whether an institution has a very strict formulary with a minimum number of items or a less-restricted formulary that excludes items that are significantly inferior is sometimes a matter of philosophy. The former will cut down the pharmacy department’s inventory and often save money through avoidance of highly priced products, but may only be practical in closed health maintenance organizations (HMOs) where the same formulary is used in both the inpatient and ambulatory environments. In cases where physicians are free to prescribe whatever products they prefer in the ambulatory environment, they have been shown to have difficulty in remembering what products are contained on the formularies of third-party payers.114 Therefore, the increased time necessary for pharmacists to contact physicians for order changes may lead to the disruption of patient care. As a result, a less-restricted formulary may be more practical. As an example, a patient is admitted to the hospital on a nonformulary medication. While there would be other satisfactory medications in the same therapeutic category on the formulary, it may be best to simply allow use of the nonformulary product, rather than adding another complicating factor to the patient’s hospital treatment by attempting to change therapy. Pharmacist and physician time would also be saved.

Even in cases where an institution has a strict and enforced drug formulary, it should be noted that there are occasions when it is necessary to prescribe a drug that is not on the drug formulary. This might be due to a patient with a rare illness, a patient who does not respond or has intolerable side effects to the formulary drugs, a patient stabilized on a nonformulary medication where it would be difficult or dangerous to change, a conflict between the institutional formulary and the patient’s insurance company formulary,115 or some other valid reason. A mechanism must be in place to promptly obtain the particular drug when it is shown to be necessary (the National Committee for Quality Assurance [NCQA] requires such a mechanism for HMOs,116 as does TJC for other hospitals,15 but it must try to prevent physicians from ordering nonformulary drugs “because I said so!”). Some institutions require specific request forms to be filled out (see example in Appendix 12–2), sometimes with a cosignature from the physician’s department head, or at least require a consultation between a pharmacist and the physician before the drug is obtained. Also, patients may be charged more for the nonformulary medications. In some HMOs and insurance company plans, the physicians or pharmacies may be financially penalized for use or overuse of nonformulary medications.117 Whatever mechanism is used, it is important to make it easy to obtain necessary nonformulary medications, but difficult to obtain unnecessary medications, otherwise the benefits of the formulary system may be negated.56 Also, it is necessary to track which nonformulary drugs are being used regularly and why that is happening because it may be worthwhile to add an agent to the drug formulary.118

Some physicians feel that a drug formulary serves only to keep costs down, at the expense of good patient care.119 These physicians must be reassured that there is evidence to support that a good formulary does keep expenses down120 without negatively affecting care,121 although in some cases the costs are merely transferred to other hospital expenses.122,123 One study demonstrated that a well-controlled formulary or therapeutic substitution (substituting a different medication that is effective for the disease being treated for the one ordered by the physician) results in 10.7% lower drug costs per patient day, and both a well-controlled formulary and therapeutic substitution together could cause 13.4% lower drug costs per day.124 Some physicians do not like formularies because they consider them to be a limitation to their authority.119 It is necessary to keep in mind that when physicians become a part of a medical staff or sign up to participate in some managed care group they are given privileges not rights. The privileges generally do include limitations on what medications they can prescribe, and when and how they can prescribe them. If a drug formulary system is run well, there is little reason to feel there are inadequate drugs available; however, it does take some effort for the physician to learn to use the drugs available rather than the drugs they normally prescribe. An effort must be made to collaborate with physicians in this regard and to reassure them that every effort is being made to ensure the best drugs are available for the patients. Additionally, all changes to the drug formulary must be quickly and effectively communicated to the physicians to avoid confusion. A lack of such communication can negate some of the benefits of the formulary and lead to poor physician/pharmacist relations.122 Also, it is important for physicians to be aware that it is the medical staff that makes these decisions, in order to avoid pharmacy being perceived as the policeman who is waiting to jump on the unsuspecting physician.125 Increasingly, physicians will enter prescription orders into the computer, which can quickly inform the physician of formulary drug choices and guide therapeutic decisions. Currently, however, pharmacists often have to tactfully contact the physician about nonformulary drugs in order to make a formulary system work.

Similarly, pharmacies filling prescriptions for an HMO must be kept informed of the formulary status of drugs. One suggestion is to have a help desk to answer pharmacist questions and to provide information.126

Oftentimes, the drug formularies will have a number of other sections that may include information about the P&T committee and pharmacy department, policy and procedure information (e.g., how to obtain nonformulary drugs, how to request a drug be placed on the formulary), laboratory test information, dietary supplement charts, pharmacokinetics information, approved abbreviations, sodium content, nomograms, dosage equivalency charts, apothecary/metric equivalents, drug–food interactions, skin test directions, cost data, antimicrobial therapy charts, and any other brief clinical information tables felt to be necessary. Use of linking in Web sites can make such information much more readily available and usable, since users can navigate back and forth between these tables and the drug list. MCOs may need to include the procedure they use to limit choice of drugs by physicians, pharmacists, and patients.16,127

In institutional pharmacies, a hardcopy book was normally published once a year in the past. Often it was published in a pocket-size format that could be carried in lab coats by physicians, pharmacists, and nurses. There may also have been a larger loose-leaf binder published that could be updated regularly throughout the year. Such a book is no longer justified.128

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree