Chapter Thirteen

Drug Evaluation Monographs

Learning Objectives

After completing this chapter, the reader will be able to

• Describe and perform an evaluation of a drug product for a drug formulary.

• List the sections included in a drug evaluation monograph.

• Describe the overall highlights included in a monograph summary.

• Describe the recommendations and restrictions that are made in a monograph.

• Describe the purpose and format of a drug class review.

![]()

Key Concepts

Introduction

![]() The establishment and maintenance of a drug formularyrequires that drugs or drug classes be objectively assessed based on scientific information (e.g., efficacy, safety,1 uniqueness, cost, and other appropriate items), not anecdotal prescriber experience. The way to decide which drug is best for formulary addition is to rationally evaluate all aspects of the drug in relation to similar agents. In particular, it is necessary to consider need, effectiveness, risk, and cost (overall, including monitoring costs, discounts, rebates, and so forth)—often in that order. Some other issues that are evaluated include dosage forms, packaging, requirements of accrediting or quality assurance bodies, evidence-based treatment guidelines, prescriber preferences, regulatory issues, patient/nursing convenience, advertising, and consumer expectations.2 There is increasingly more emphasis on evaluating clinical outcomes from high-quality trials, continuous quality assurance information, comparative efficacies,3 pharmacogenomics, and quality of life.4 Even such a factor as the public image of the institution may have an impact on the decision to add a drug to the formulary. An in-depth drug evaluation monograph can be prepared to assist in this process as described below.

The establishment and maintenance of a drug formularyrequires that drugs or drug classes be objectively assessed based on scientific information (e.g., efficacy, safety,1 uniqueness, cost, and other appropriate items), not anecdotal prescriber experience. The way to decide which drug is best for formulary addition is to rationally evaluate all aspects of the drug in relation to similar agents. In particular, it is necessary to consider need, effectiveness, risk, and cost (overall, including monitoring costs, discounts, rebates, and so forth)—often in that order. Some other issues that are evaluated include dosage forms, packaging, requirements of accrediting or quality assurance bodies, evidence-based treatment guidelines, prescriber preferences, regulatory issues, patient/nursing convenience, advertising, and consumer expectations.2 There is increasingly more emphasis on evaluating clinical outcomes from high-quality trials, continuous quality assurance information, comparative efficacies,3 pharmacogenomics, and quality of life.4 Even such a factor as the public image of the institution may have an impact on the decision to add a drug to the formulary. An in-depth drug evaluation monograph can be prepared to assist in this process as described below.

![]() The drug evaluation monograph provides a structured method to review the major features of a drug product. Once a monograph is prepared, it can easily be used as a structured template or overview of a drug product. That allows for easy comparison or contrast to other products that may be used for the same indication or that are in the same product class. Commercially prepared monographs can also be obtained from several sources that can be used as is or with modifications to suit the needs of the institution. If this latter method is used, be aware that the quality of the commercial monographs may vary, even from the same publisher, and they may need extensive updating. Often, writing a new drug evaluation monograph may be easier than improving a commercial monograph. When a pharmacy and therapeutics (P&T) committee desires to review an entire class of drugs, the drug category review is often another method used. Drug class reviews are often more lengthy than a single product drug evaluation monograph; however, they can also use a similar structure and format. Hospitals, health systems, and managed care organizations review an entire class of drugs on a scheduled basis, which must be at least annually, according to accreditation standards.5 This allows an organization the opportunity to reevaluate the formulary status of products in light of new publications or trials, new products that have entered the market, or oftentimes reevaluate a drug class for possible deletion of particular products from the class. Samples of drug class reviews prepared by the Veterans Administration are available on the Internet at http://www.pbm.va.gov/clinicalguidance/drugclassreviews.asp.

The drug evaluation monograph provides a structured method to review the major features of a drug product. Once a monograph is prepared, it can easily be used as a structured template or overview of a drug product. That allows for easy comparison or contrast to other products that may be used for the same indication or that are in the same product class. Commercially prepared monographs can also be obtained from several sources that can be used as is or with modifications to suit the needs of the institution. If this latter method is used, be aware that the quality of the commercial monographs may vary, even from the same publisher, and they may need extensive updating. Often, writing a new drug evaluation monograph may be easier than improving a commercial monograph. When a pharmacy and therapeutics (P&T) committee desires to review an entire class of drugs, the drug category review is often another method used. Drug class reviews are often more lengthy than a single product drug evaluation monograph; however, they can also use a similar structure and format. Hospitals, health systems, and managed care organizations review an entire class of drugs on a scheduled basis, which must be at least annually, according to accreditation standards.5 This allows an organization the opportunity to reevaluate the formulary status of products in light of new publications or trials, new products that have entered the market, or oftentimes reevaluate a drug class for possible deletion of particular products from the class. Samples of drug class reviews prepared by the Veterans Administration are available on the Internet at http://www.pbm.va.gov/clinicalguidance/drugclassreviews.asp.

Whether or not the monograph is commercial or prepared by a member from within the organization, the material should reflect the local conditions or current prescribing practices and may be sent to P&T committee members at a reasonable time before the meeting in order to allow full consideration of the information. In order to prevent drug company representatives or others from obtaining the material, however, some institutions only distribute this material for review during the meeting and then require the materials to be returned at the end of the meeting. Some institutions even number each monograph with a unique numbering system to assist in tracking the return of P&T committee documents.

Although there are recommendations concerning monograph contents,2,6 information that may be valuable and specific to an institution, and necessary for an objective review of the product, is commonly missing.7 An outline of a sample monograph is found in Appendix 13–1. Each of the sections of this monograph will be discussed below. An example of some of the information found in the various parts of a monograph is seen in Appendix 13–2. This sample monograph meets or exceeds the recommendations of the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP),6 and should serve as a good example for most circumstances. Guidelines published by the Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy (AMCP)2,8 and The Joint Commission (TJC)5 are also noted and discussed for situational applicability. The AMCP format is actually the standard recommended by an organization for manufacturers to submit data to managed care organizations. It is designed to restrict the marketing impact of the company in providing information and, while it has applicability as to how an institution may evaluate a drug, it also has restrictions as to the amount of information that it can cover in some areas that may make it undesirable in some cases. However, it may be very worthwhile for institutions or other organizations to request this information from the drug company, preferably, well in advance of the time it is needed. Please note, in some cases this request may require signing a nondisclosure agreement, since it may contain proprietary information.2

Overall, the precise monograph should be tailored to the institution, organization, patient population, clinic, and so forth. Several sections not recommended by ASHP have been added to increase the utility of the monograph for other sites of practice, including ambulatory clinics, pediatric institutions, long-term care facilities, managed care or pharmacy benefit managers, or even Medicare or Medicaid formularies. Also, in some cases, the information has been divided into multiple sections or subsections to increase clarity. This format can also be used to evaluate whole classes of drugs. In most cases, a specific drug is compared to others in the same class. The only difference in a class review is that one drug is not receiving the greatest attention; all drugs are being compared with equal attention. Comparative charts and tables are often more prevalent in drug class reviews, as they can serve as a concise method to provide an overview of comparative features for the products in a particular drug class.

Specific formats, differing somewhat from the one presented here, may be required by organizations or governments. For example, Australia (http://www.tga.gov.au/industry/pm-argpm.htm),9 Ontario, Canada (http://www.health.gov.on.ca/english/providers/pub/drugs/dsguide/dsguide_mn.html),10 and the United Kingdom (http://www.nice.org.uk/aboutnice/howwework/devnicetech/technologyappraisalprocessguides/technology_appraisal_process_guides.jsp)11 have very specific published guidelines that need to be followed for a drug product to be considered for their formularies. The process recommended in this chapter appears to be common in both Canada and the United States, and has been recommended in Australia.12 Where appropriate, features of these formats have been incorporated into the description presented in this chapter. While the format described in this chapter does provide much of the information in those government standards, with the exception of details about product manufacturing and specific pricing for the particular country, the order and amount of information is often different and the reader is referred to those standards for details.

Before discussing details about monograph preparation, it should be emphasized that the drug monograph is a powerful tool for the pharmacy to guide the rational development of a drug formulary. Although the pharmacy department or an individual pharmacist may have few, if any, votes in the ultimate adoption of a formulary agent, the monograph guides the evaluation process and is likely to be a major factor in the final decision. While monograph preparation can be very time consuming, it is extremely important and should be given proper attention. The structured evaluation process of a drug monograph, in many cases, is the only time a full, fair, and balanced review of a drug may be presented to a practitioner. Pharmacists have a unique role in the preparation of a monograph in that they view the drug product from a whole and macroeconomic view—all aspects of the drug product are objectively reviewed in a monograph, whereas, oftentimes when a prescriber is presented information about a new drug product, they may be basing their use or nonuse of the product on a single study, package insert data, pharmaceutical representative information, or some other microeconomic view of a drug product that may or may not represent the full utility of the drug product.13,14

In addition to FDA-regulated drug products, pharmacists need to be aware of complementary/alternative medicine use, along with the responsibilities and implications that it has for pharmacy services. These products can only be marketed as dietary substances, since the FDA does not regulate herbal products, so manufacturers and distributors cannot make specific health claims. Although there may be minimal scientific evidence regarding efficacy and safety of these products, pharmacists must provide information relating to all therapeutic agents patients are receiving, preparing a drug monograph for the P&T committee, much the same as for any FDA-approved product. This can also follow the format described in this chapter.15

The following sections describe the parts of the drug monograph, as shown in the appendices. Please note that skills in information retrieval (see Chapter 3), drug literature evaluation (see Chapters 4 and 5), professional writing (see Chapter 9), and areas covered in various other chapters must be employed when preparing a drug evaluation monograph.

Drug Evaluation Monograph Sections

SUMMARY PAGE

The first page of the monograph is essentially a summary of the most important information concerning the drug, and includes a specific recommendation of the action to be taken on the product. Some P&T committees only review this first sheet; however, the remainder of the document should be prepared in order to completely evaluate a drug product and provide a record of all that was taken into consideration. The summary and recommendation could be placed at the end of the monograph, but it is probably best to keep it on the front to make it easier to refer to during the meeting.

The format of the summary page usually begins with general institutional information. Following the name header, specific introductory information about the product is included. The generic name, trade name, and manufacturer are self-explanatory, but the classification may require some explanation. This is meant to give the readers a very quick way of classifying the agent in their head. It includes the prescription/controlled substance status, American Hospital Formulary Service (AHFS) classification, and FDA classification. It may also contain other classification schemes used by particular organizations, such as the Veteran’s Administration. Managed care organizations may use more detail drug product identification schemes, such as those established by First DataBank (http://www.fdbhealth.com).

The AHFS classification can be found in the AHFS Drug Information reference book, published by the ASHP. This classification can help the reader determine where this new agent falls in therapy. Most of the time new drugs will be evaluated for possible formulary addition before they are actually placed in that book, so it will be necessary to consult the therapeutic classification table in the front of the AHFS Drug Information reference book or online at http://www.ahfsdruginformation.com/class/index.aspx to decide where the product fits. The classification of similar products listed in AHFS Drug Information can also be checked before deciding where to categorize the new product.

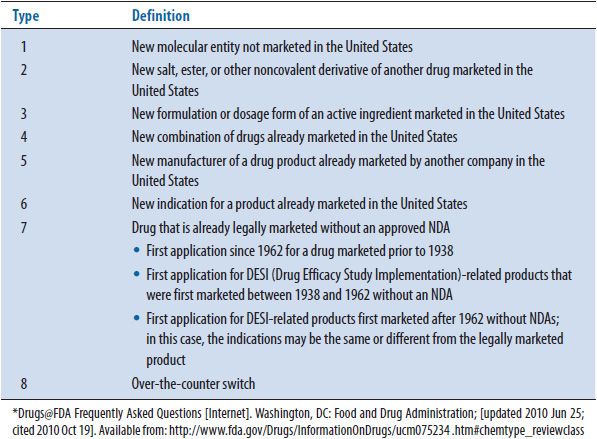

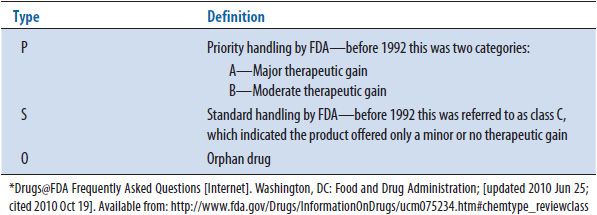

The FDA classification is given to nonbiologic products during the review process and is finalized when the new drug application (NDA) is approved. This classification gives some idea of the importance of the product. The classification consists of Chemical Type classification (see Table 13–1) and Therapeutic Rating classification (see Table 13–2). An FDA classification of 1P (or 1A prior to 1992) would indicate a drug that was given a priority review status by the FDA. This means that the product offered a therapeutic advance over existing products in the market, may be for a new disease state, or may represent a new drug class. The FDA generally reviews these products in an expedited manner, often not requiring as many clinical trials or a lower number of patients enrolled in the trials before the drug is approved to be on the market. In contrast, a classification of 3S (or 3C prior to 1992) is probably a me-too product, meaning that it is an additional product in a class of medications that is already on the market and is similar in many ways to the other products already marketed. These products are generally reviewed by the FDA in a standard review manner and do not receive an expedited review process. Knowing and understanding the FDA classification status of a product can assist a reviewer in preparing the drug evaluation monograph in several ways. First, if the reviewer knows that the product they are reviewing has an FDA classification status of 1P, the reviewer will often have to compare the product to a drug outside of the class of the product they are reviewing. For example, if a new class of antibiotics was developed called ketolides, the reviewer will not have any other drugs in the class to compare the product to, and, therefore, he or she may need to search for studies or review articles of products that fall in other classes of antibiotics, such as the macrolides. Oftentimes in cases in which cancer chemotherapy medications are approved for a treatment that was previously treated by nondrug therapy, a surgical procedure or radiation therapy may be the best comparator for the product. In the case of products that are given an FDA classification status of 3S, the reviewer generally will be able to prepare a head-to-head comparison of the product to another product that is in the same drug class. For example, if a new hydroxymethylglutaryl-coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase inhibitor was approved by the FDA, the reviewer would normally want to the compare the product to other HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors. Usually, when 3S or standard review products enter the market, if there are already a number of similar products available in the market, the manufacturer will conduct trials with the product compared to others in the same class. This product is generally then referred to as the comparator or gold standard product. The reviewer will want to discuss the comparator product and any other similar agents in the class. This can assist the decision makers in the P&T committee in reviewing the new product if they are already familiar with other products in the class.

TABLE 13–1. FDA CLASSIFICATION BY CHEMICAL TYPE*

TABLE 13–2. FDA CLASSIFICATIONS BY THERAPEUTIC POTENTIAL*

Additional product introductory information may include the product’s patent exclusivity date and/or the product’s patent expiration date. This information can generally be located on the FDA’s Web site at http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/drugsatfda/index.cfm. A particular institution may request additional or specific information that may be relevant to include in the introductory information. It is also common to provide a list of similar agents.

The summary itself is a brief overview of the important aspects of the drug product. If there are similar products or different drugs used for the same indication, it is important to state how the drug being reviewed compares to those products. If a comparison between the agent in question and some other treatment is possible, that comparison must make up the bulk of the section, just as the comparison must be a prominent feature in every other section of the document. The summary will include information on the efficacy, safety (e.g., adverse effects and drug interactions16), uniqueness, cost, treatment need in the institution, inpatient versus outpatient needs, potential for inappropriate use,17 and other factors, such as the likelihood patients would be more compliant with one agent or another18,19 or how the therapy fits into published clinical guidelines. Information should be limited in this section to those items where a drug has a definite advantage/disadvantage or, if products are similar, where there would be concern about the possibility of a clinically significant difference. Items that are not clinically significant and not likely to be of concern should be left out of the summary to avoid distractions. In cases where the new drug under evaluation is indicated for a disease that has normally received nondrug treatment (e.g., surgery, radiation, and physical therapy), the drug should be compared to that standard treatment. It is worth pointing out that the summary should be just that—a summary of the material presented in the body of the document. Similar to the conclusion of a journal article, this is not the place to put new material or, for that matter, to provide citations; both of those items belong in the body.

![]() Finally, a definite recommendation must be made based on need, therapeutics (including outcome data and the use of evidence-based clinical guidelines), adverse effects, cost (full pharmacoeconomic analysis, if possible), and other items specific to the particular agent (e.g., evidence-based treatment guidelines, dosage forms, convenience, dosage interval, inclusion on the formulary of third-party payers, hospital antibiotic resistance patterns, and potential for causing medication errors20), usually in that order.21,22 In hospitals, a new accreditation requirement makes it necessary to list the indications for use that the drug the P&T committee is approving; this must be a specific list, although it is okay to give a blanket authorization to FDA-approved indications in general.23 (Note: The requirement that drugs be approved for specific indications is likely to only be practical in hospitals where there is computerized order entry and the physician has to state the indication). When making formulary recommendation as it pertains to third-party payers, consideration should also be given to the placement of the formulary agent into a multitiered copayment system where the copayment varies according to the cost of the drug and/or formulary status. The member is required to pay these varying amounts of copayment out of pocket at the time the prescription is filled. In general if the drug is a generic, the placement is at the first tier that has the lowest copayment. If the drug is a brand name drug preferred by the health plan, it is usually placed in the second tier with a higher copayment. All other brand name, nonpreferred drugs are usually placed in the third tier with the highest copayment. Drugs in the third tier, the nonpreferred agents, usually have therapeutic alternatives in either the first or second tier. Members are encouraged to talk to their prescribers about switching to the more cost-effective, therapeutic alternative drugs in the lower tiers.24,25 Tier designation or formulary status may change, based on the discretion of the health plan and/or pharmacy benefits management (PBM), in the absence of significant new clinical evidence.26 Quality-of-life information and patient preferences should be considered, if possible. Recommendations for third-party payers may also include a step therapy approach, quantity limits on the prescription, prior authorization, and coverage rule criteria in order for the drug to be covered. Third-party payers may require some drugs to have a prior authorization before being dispensed. Prior authorization is usually required for those drugs that are high cost and/or are likely to be used inappropriately. Examples include appetite suppressants and growth hormones. Prior authorization requires that predetermined guidelines must be met by the member before the drug can be covered by the third-party payer. As an example, the member may be required to try an established, less expensive drug therapy first. If this drug therapy proves to be ineffective or the patient is unable to tolerate the therapy, then the third-party payer may cover a newer, more expensive therapeutically equivalent drug.27

Finally, a definite recommendation must be made based on need, therapeutics (including outcome data and the use of evidence-based clinical guidelines), adverse effects, cost (full pharmacoeconomic analysis, if possible), and other items specific to the particular agent (e.g., evidence-based treatment guidelines, dosage forms, convenience, dosage interval, inclusion on the formulary of third-party payers, hospital antibiotic resistance patterns, and potential for causing medication errors20), usually in that order.21,22 In hospitals, a new accreditation requirement makes it necessary to list the indications for use that the drug the P&T committee is approving; this must be a specific list, although it is okay to give a blanket authorization to FDA-approved indications in general.23 (Note: The requirement that drugs be approved for specific indications is likely to only be practical in hospitals where there is computerized order entry and the physician has to state the indication). When making formulary recommendation as it pertains to third-party payers, consideration should also be given to the placement of the formulary agent into a multitiered copayment system where the copayment varies according to the cost of the drug and/or formulary status. The member is required to pay these varying amounts of copayment out of pocket at the time the prescription is filled. In general if the drug is a generic, the placement is at the first tier that has the lowest copayment. If the drug is a brand name drug preferred by the health plan, it is usually placed in the second tier with a higher copayment. All other brand name, nonpreferred drugs are usually placed in the third tier with the highest copayment. Drugs in the third tier, the nonpreferred agents, usually have therapeutic alternatives in either the first or second tier. Members are encouraged to talk to their prescribers about switching to the more cost-effective, therapeutic alternative drugs in the lower tiers.24,25 Tier designation or formulary status may change, based on the discretion of the health plan and/or pharmacy benefits management (PBM), in the absence of significant new clinical evidence.26 Quality-of-life information and patient preferences should be considered, if possible. Recommendations for third-party payers may also include a step therapy approach, quantity limits on the prescription, prior authorization, and coverage rule criteria in order for the drug to be covered. Third-party payers may require some drugs to have a prior authorization before being dispensed. Prior authorization is usually required for those drugs that are high cost and/or are likely to be used inappropriately. Examples include appetite suppressants and growth hormones. Prior authorization requires that predetermined guidelines must be met by the member before the drug can be covered by the third-party payer. As an example, the member may be required to try an established, less expensive drug therapy first. If this drug therapy proves to be ineffective or the patient is unable to tolerate the therapy, then the third-party payer may cover a newer, more expensive therapeutically equivalent drug.27

Recommendations should be specific to the circumstances in the institution, hospital system, third-party payer plan, and/or other organization in which it is being considered. In some cases, an institution may have a subformulary that is available for only a specific group of patients (e.g., Medicaid).28 Recommendations to conduct drug use evaluation on the drug (see Chapter 14), clinical guidelines to be followed (see Chapter 7), how physicians are to be educated about the new drug, and other items may also be necessary. Education may range from a simple newsletter or Web page, to a specific educational program and certification required before a physician can prescribe a drug product.29

Some people strongly object to the presence of specific recommendations being placed in the document. This may be because they do not feel it is appropriate for them to make these decisions; however, this should not be a concern if adequate research was done in preparing the evaluation. Sometimes, they have a philosophy that an unbiased decision should be reached only through a group consensus after discussing the matter in the P&T committee meeting; however, that too should not be a concern. For one thing, the person preparing the document, who also obtains input from other appropriate individuals, is in the best situation to advance a logical recommendation. Second, without a recommendation, the discussion does not have a foundation to begin with—allowing the discussion to wander aimlessly to some conclusion that may not make optimal sense. Third, the lack of a specific recommendation allows emotion and conjecture to overcome evidence and science. The provision of a specific recommendation is one of the best opportunities for pharmacists to have a deep and wide-ranging impact on patient care, and should not be neglected.

![]() The recommendation must be supported by objective evidence (presented in the summary). Subjective factors that are likely to be significant from the point of view of all involved parties (i.e., physicians, pharmacists, nurses, and patients) should also be considered. Decision analysis can be used to show the best drug at the least cost (effectively this is pharmacoeconomic analysis—see Chapter 6 for details).27,30–33 Other factors may also be considered and given weight to indicate importance (e.g., multiattribute utility theory34). These methods may be commonly seen in managed care.35 They look at the possible decisions and their likely outcome, allowing a decision to be made that is likely to lead to the most desirable outcome. Meta-analysis may also find a place in the decision-making process36; however, it seems unlikely that most individuals evaluating products for formulary addition would have the skill or time to use that method. Tentative recommendations should be discussed with appropriate physicians and any clinical pharmacists specializing in that area of therapy before the recommendation is finalized. For example, if a cardiac medication is being evaluated, one or more cardiologists should be consulted to identify their concerns and desires. That does not mean the recommendation should necessarily be changed to what a prescriber wants. If the objective evidence supports the original recommendation, that is the one that should be made; however, it is necessary to demonstrate that the prescribers’ concerns were addressed.

The recommendation must be supported by objective evidence (presented in the summary). Subjective factors that are likely to be significant from the point of view of all involved parties (i.e., physicians, pharmacists, nurses, and patients) should also be considered. Decision analysis can be used to show the best drug at the least cost (effectively this is pharmacoeconomic analysis—see Chapter 6 for details).27,30–33 Other factors may also be considered and given weight to indicate importance (e.g., multiattribute utility theory34). These methods may be commonly seen in managed care.35 They look at the possible decisions and their likely outcome, allowing a decision to be made that is likely to lead to the most desirable outcome. Meta-analysis may also find a place in the decision-making process36; however, it seems unlikely that most individuals evaluating products for formulary addition would have the skill or time to use that method. Tentative recommendations should be discussed with appropriate physicians and any clinical pharmacists specializing in that area of therapy before the recommendation is finalized. For example, if a cardiac medication is being evaluated, one or more cardiologists should be consulted to identify their concerns and desires. That does not mean the recommendation should necessarily be changed to what a prescriber wants. If the objective evidence supports the original recommendation, that is the one that should be made; however, it is necessary to demonstrate that the prescribers’ concerns were addressed.

Overall, the items most likely to be added to the formulary include those that are unique, that serve the specific population, that are most cost-effective, and, unfortunately, those with the biggest marketing drive by the marketer. Multiple ingredient products or products that are the extended-release or other variations on the patent of a product are least likely to be added in the institutional setting.37

The recommendation should be whatever logical conclusion is supported by the objective evidence and the needs of the health care system, including health care staff needs, distribution concerns, drug administration, and drug availability. Whenever possible, at least in the case of recommendations prepared for an institutional pharmacy, it is best to follow the ASHP guidelines for recommendations, which would place the drug into one or a combination of the following groups6:

• Added for uncontrolled use by the entire medical staff.

• Added for monitored use—No restrictions placed on use, but the drug will be monitored via a quality assurance study (e.g., drug usage evaluation and medication usage evaluation) to determine appropriateness of use. This is a tie-in to the institution’s quality assurance/drug usage evaluation process.38 Note: This category does not mean that the patient is monitored, since that is necessary for every drug. It means that the quality and appropriateness of how the drug is used is monitored.

• Added with restrictions—The drug is added to the drug formulary, but there are restrictions on who may prescribe it and/or how it may be used (e.g., specific indications, certain physicians or physician groups, and certain policies to be followed).

• Conditional—Available for use by the entire medical staff for a finite period of time.

• Not added/deleted from formulary.

Note, there may be different recommendations presented for specific strengths, forms, sizes, and so forth of a drug being reviewed; however, being that specific sometimes does not result in any real benefit and may only make things more complicated to manage, with little improvement in drug therapy or decrease in costs.39 Also, remember that, in any of the above, there is now a requirement to provide a specific list of approved indications for which the drug may be used.5

Most drugs should be added for uncontrolled use or, at the other extreme, not be added, simply because the three other categories cause greater work for the pharmacy or other departments. As a side point, if a recommendation to not add the drug to the formulary is approved, it is often good to require a time period before the drug can be considered again (typically 6 months) to prevent heavy political action pushing through approval of a less than desirable drug, just because the P&T committee gets tired of having it requested every month. Monitored use is occasionally needed if there is concern that a drug might be used in some inappropriate manner or has a great risk for adverse events. A limited drug usage evaluation would be conducted until it is evident that the drug is being appropriately used or not causing adverse events. One example where monitored use might be considered is an expensive biotechnology product that only has one normal dose, but multiple investigational doses, where it could be inappropriately prescribed without an investigational protocol. Also, a very toxic product might be monitored to see if adverse effects are appropriately addressed by the prescriber. As electronic drug usage evaluation becomes standard, monitoring may be used to a greater extent, but is seldom justified in systems requiring the pharmacist to manually collect data. Conditional addition to the formulary is a recommendation of last resort, simply because it is much easier to keep a drug off the formulary rather than try to delete an inappropriate drug that is being used by prescriber. This type of approval might be used when it is very difficult to clearly determine whether an agent will benefit the institution, if available data are limited at the time of the P&T meeting. If conditional approval is given, it is absolutely necessary to specify when the P&T committee will reconsider whether the drug should be retained on the formulary.

The added-with-restrictions choice deserves more explanation. Occasionally, there are drugs that should be added to a drug formulary, but are dangerous,40 or prone to misuse or overuse. This could include agents such as antineoplastics, thrombolytics, and fourth or fifth generation cephalosporins.41 In such cases, it may be desirable to limit the use of the drugs in some manner.42

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree