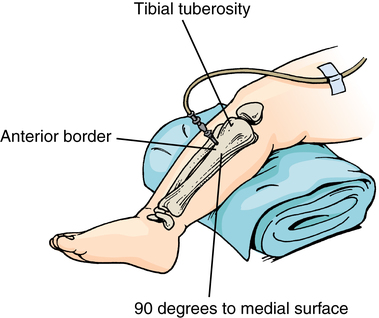

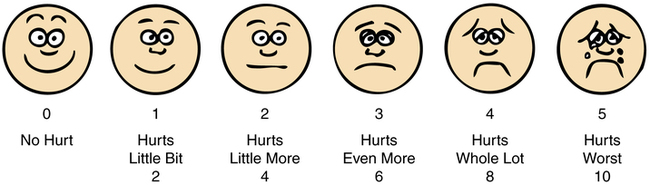

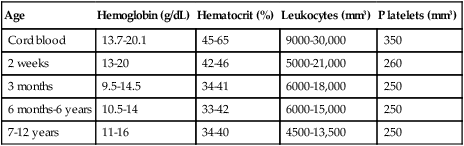

Chapter 8 After studying this chapter, the learner will be able to: • Describe pediatric patient care in terms of developmental stages. • Identify age-specific considerations in the care of pediatric patients. • List several procedures that are performed on pediatric patients. The surgical problems peculiar to children from birth to postpuberty are not limited to any one area of the body or to any one surgical specialty. Malformations and diseases affect all body parts and therefore may require the skills of any of the surgical specialists. However, pediatric surgery is a specialty in itself and is not adult surgery scaled down to infant or child size. Indications for surgery include congenital anomalies, acquired disease processes, and trauma. Many of these conditions are treatable or curable with surgical intervention. (Additional information can be found at www.pedisurg.com.) Vertebral defect, such as spina bifida or myelomeningocele Anal malformation, such as imperforate anus Cardiac anomaly, such as patent ductus arteriosus or ventricular and atrial septal defects Renal anomaly, such as horseshoe kidney and renal dysplasia Coloboma (split iris) defect in the eye Hearing impairment caused by structural defects Retardation caused by brain anomalies • Recognition of differences between pediatric patients and adults. • Accurate diagnosis and earlier treatment, which facilitates a more favorable outcome, especially in the fetus and preterm neonate. Neonatology is a growing subspecialty of pediatrics. • Understanding of preoperative preparation of the patient and family. • Availability of total parenteral nutrition (TPN) and other measures of supportive care for perioperative pediatric management. • Advances in anesthesiology, including new agents, perfection of techniques of administration, and an understanding of the responses of pediatric patients to anesthetic agents. • Refinements in surgical procedures and instrumentation. • Understanding of postoperative care. Larger facilities have neonatal and pediatric intensive care units. The nursing process is tailored to meet the unique needs of each pediatric patient. Assessment and nursing diagnoses are based on chronologic, psychological, and physiologic factors specific to each patient. The plan of care should reflect consideration for age and reflect interventions modified according to the child’s developmental stage as identified in Table 8-1. TABLE 8-1 Psychologic Developmental Stage Theories Developmental theorists emphasize that although the child has reached a certain age or physical size, psychological growth is the key parameter by which communication is measured. Understanding individual differences enables the perioperative team to develop a positive rapport with the patient and family, which facilitates attainment of expected outcomes.9 Not every patient of a particular age-group meets standardized height and weight criteria; children may be short or tall or thin or heavy for their age. Although norms have been established by age-groups, the plan of care should reflect consideration for individual differences. (Additional information about developmental theory and theorists in PowerPoint format can be found at www.coping.org.) The chronologic age of the patient is a primary consideration in the development of the plan of care. An age-related baseline is a useful beginning for effective assessment of pediatric patients.6 Parents take comfort in knowing that their children are being cared for in an age-appropriate manner and not like miniature adults. Use of a pediatric focus with babies and children creates an atmosphere specifically geared toward safety and may minimize risks such as medication dosage errors. In concert with the care of adult patients and Universal Protocol for patient safety in the OR, a pediatric checklist should be used.6 No child exactly meets all criteria in chronologic versus emotional age. Authors may vary in small age increments; however, no author can state that all children fit all templates exactly because each is an individual. Terminology used to approximately categorize ages of pediatric patients includes the following: 1. Embryo: Not compatible with life. 2. Fetus: In utero after 3 months of gestation. 3. Newborn infant, referred to as a neonate: a. Potentially viable: Gestational age more than 24 weeks; birthweight more than 500 g; capable of sustaining life outside the uterus (as defined by the WHO). b. True preterm: Gestational age less than 37 weeks; birthweight 2500 g or less. c. Large preterm: Gestational age less than 38 weeks; birthweight more than 2500 g. d. Term neonate: Gestational age 38 to 40 weeks; birthweight greater than 2500 g, usually between 3402 and 3629 g (if less than 2500 g, the neonate is considered small for gestational age [SGA]). 4. Neonatal period: First 28 days of extrauterine life. 5. Infant: 28 days to 18 months. 7. Preschool age: 2 ½ to 5 years. Assessment of psychological development is based on age-related criteria (see Table 8-1) but includes assessment of individual differences. Comparison of established norms and assessment data is helpful in developing the plan of care. Environmental and parental influences can cause variance in affect, attitude, and social skills. Environmental influences on psychological development include ethnic, cultural, and socioeconomic factors.9 The age of the patient may indicate the level of involvement with the environment. For example, an infant may have exposure only to immediate family members for external stimuli, but a preschool child may have daily experience with children in preschool and other children. Coping and social skills may be developed, depending on the child’s developmental stage.a,b Unexplained marks or bruises may be signs of physical abuse. Health care personnel are required to report suspected child abuse.2 Photographs are useful in the documentation of physical findings. Abused children may be afraid of punishment for revealing the origin of an injury.2 Some physical findings suggestive of abuse discovered during the physical examination or surgical skin preparation may include but are not limited to: 2. Genital injuries, such as tears or sexually transmitted diseases. 3. Human or animal bite marks. 4. Patterned bruises or skin tears. A small frail child may have a congenital cardiac deformity or a malabsorption syndrome. Abuse or neglect may be manifested as a nutritional deficit. An extremely thin malnourished adolescent may be intentionally bulimic or anorexic in response to a psychological body image problem. An obese child may have an endocrine disease or a psychological disturbance that causes overeating. These issues are important considerations because most dosages of medications given to pediatric patients are based on body weight in kilograms.1 Absorption and metabolism of medication are influenced by the same physiologic parameters that govern nutritional status. The hemoglobin level is lowest at 2 to 3 months of age (Table 8-2). The blood volume of the average newborn is 250 mL, approximately 75 to 80 mL/kg of body weight (Table 8-3). A subtle sign of blood loss is a narrowed pulse pressure less than 20 beats per minute. Significant blood loss requires replacement. Blood is typed and crossmatched in readiness. Although blood loss is small in most cases, a loss of 30 mL may represent 10% to 20% of circulating blood volume in an infant. The small margin of safety indicates the need for replacement of blood loss exceeding 10% of circulating blood volume. When replacement exceeds 50% of the estimated blood volume, sodium bicarbonate is infused to minimize metabolic acidosis. TABLE 8-2 Pediatric Hematologic Value Ranges TABLE 8-3 IV infusions should be administered with the following precautions: • Dehydration should be avoided. Therapy for metabolic acidosis, should it develop, is guided with measurement of pH, blood gas values, and serum electrolyte levels. • Blood volume loss should be measured as accurately as possible and promptly replaced. In an infant, rapid transfusion of blood may produce transient but severe metabolic acidosis because of citrate added as a preservative. • IV fluids and blood should be infused through pediatric-size cannulated needles or catheters connected to drip chamber adapters and small solution containers. Umbilical vessels may be used for arterial or venous access in newborns less than 24 hours after birth. In extreme circumstances, the umbilical vein can be accessed through a small infraumbilical incision and cannulated from inside the peritoneal cavity for rapid infusion. Scalp veins are used frequently on infants. If venous access cannot be quickly established, intraosseous infusion may be indicated for fluid replacement (Fig. 8-1). A cutdown on an extremity vein, usually the saphenous vein, may be necessary for toddlers and older children. An extremity should be splinted to immobilize it. A 150-mL or 250-mL solution drip chamber, sometimes referred to as Burette, Buritrol, Metriset, or Soluset, is used to help avoid the danger of overhydration. This chamber is available in sizes that range from 50 to 250 mL from manufacturers such as Abbott, Braun, and Baxter. Adapters are set for accurate control of the desired flow rate. • Evaporation. When skin becomes wet, evaporative heat loss can occur. Excessive drapes can cause sweating. As sweat evaporates, it elicits a cooling effect. • Radiation. When heat transfers from the body surface to the room atmosphere, radiation heat loss can result. • Conduction. Placement of the pediatric patient on a cold operating bed causes heat transfer from the patient’s body to the surface of the bed. • Convection. When air currents pass over skin, heat loss by convection results. Cold wet diapers and blankets can cause heat loss by conduction. • A hyperthermia blanket or water mattress may be placed on the operating bed and warmed before the infant or child is laid on it. It is covered with a double-thickness blanket. The temperature is maintained between 95° F and 100° F (35° C to 37.7° C) to prevent skin burns and elevation of body temperature above the normal range. Excessive hyperthermia can cause dehydration and convulsions in the anesthetized patient. • A radiant heat lamp should be placed over the newborn to prevent heat loss through radiation. Warming lights with infrared bulbs may be used if a radiant warmer is not available. These lights should be about 27 inches (69 cm) from the infant to prevent burns; the distance should be measured. Plastic bubble wrap also provides insulation around the newborn to prevent heat loss by conduction but can cause heat loss by evaporation. • Wrapping the head (except the face) and extremities in plastic, such as plastic wrap or Webril, helps prevent heat loss in infants and small children. An aluminum warming suit or blanket may be used for toddlers and older children. Forced-air warming blankets also are effective in maintaining core temperature. Booties or socks can be helpful. • Rectal, esophageal, axillary, or tympanic probes are used to measure core temperature. A probe placed into the rectum should not be inserted more than 1 inch (2 or 3 cm) because trauma to an infant through perforation of the rectum or colon can occur. Urinary catheters with thermistor probes may be useful if urinary catheterization is indicated. Tympanic temperature measurement can be inconsistent with measurements taken elsewhere in the body and should not be the only parameter with which determination of body temperature is made. • Drapes should permit some evaporative heat loss to maintain equalization of body temperature. An excessive number of drapes, which can retain heat and put a weight on the body, are avoided. Combinations of paper, plastic, and cloth drapes may cause excessive fluid loss through diaphoresis and absorption into the drapes. • Solutions should be warm when applied to tissues to minimize heat loss by evaporation and conduction. The circulating nurse should pour warm solutions immediately before use. (Check the manufacturer’s recommendations for warming prep solutions. Some iodine-based solutions become unstable when heated. The concentration of iodine increases when the fluid portion evaporates.) • Blood and IV solutions can be warmed before transfusion by running tubing through a blood and fluid warmer. Carbon dioxide (CO2) for insufflation during laparoscopy can be warmed this way. • Blankets should be warmed to place over the patient immediately after dressings are applied and drapes are removed. The patient should be kept covered whenever possible before and after the surgical procedure to prevent chilling from the air conditioning. The heart rate fluctuates widely among infants, toddlers, and preschool children and varies during activity and at rest (Table 8-4). Infants younger than 1 year tolerate a heart rate between 200 and 250 beats per minute without hemodynamic consequence. Heart rhythm disturbance is uncommon unless a cardiac anomaly is present. Cardiopulmonary complications manifest as respiratory compromise more frequently than as cardiac dysfunction. After age 5 years, cardiopulmonary response to stress resembles that of a young adult. TABLE 8-4 *Weights from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) represent a combined estimate of weight for girls and boys. †Blood pressure from www.emedicine.com. Data from http://www.uihealthcare.com/depts/med/pediatrics/index .html; www.clinicalexam.com accessed August 11, 2011. Cardiac and respiratory rates and sounds are continually monitored in all age-groups with precordial or esophageal stethoscopy. Blood pressure, vital signs, electrocardiogram (ECG) results, and other parameters as indicated also are monitored throughout the surgical procedure (see Table 8-4). A pulse oximeter can be placed on the palm of the hand or on the midfoot of a newborn or small infant. Smaller patients experience oxygen desaturation easily. A disadvantage of pulse oximetry is that it cannot detect instantaneous drops in oxygen saturation. It gives readouts of levels that have already occurred. Because of increased carboxyhemoglobin levels, it may be ineffective for patients who have had smoke inhalation or carbon monoxide poisoning. A pulse oximeter reading of 80% is clinically diagnostic of central cyanosis. Hypoxemia can cause bradycardia to decrease oxygen consumption of the myocardium. Another method of measuring pain is the FLACC behavioral pain assessment scale (Face, Legs, Activity, Cry, and Consolability) developed by nurses and physicians at C. S. Mott Children’s Hospital at the University of Michigan Health System in Ann Arbor. The chart measures and scores five categories of behavior in pediatric patients ages 2 months to 7 years in relationship to pain (Table 8-5). TABLE 8-5 Each of the five categories is scored from 0 to 2, resulting in a total score between 0 and 10. School-age children may refer pain to a part of the body not involved in the disease process. Figure 8-2 describes the Wong-Baker FACES pain rating scale that can be used to determine the severity of pain experienced by a pediatric patient. Insecurity and fear in an older child may be more traumatic than the pain itself. Children should be observed for signs of pain (i.e., vocalizations, facial expressions, crying, body movements, physiologic parameters). Children also differ from adults in their response to pharmacologic agents; their tolerance to analgesic drugs is altered (Table 8-6). TABLE 8-6 Pediatric Sedation and Pain Management CNS, Central nervous system; IM, intramuscularly; IV, intravenously; PO, by mouth. *Additional values can be found at www.virtual-anaesthesia-textbook.com/vat/peds.htm. Data from Kyllonen M, et al: Perioperative pharmacokinetics of ibuprofen after rectal administration, Pediatr Anesth 15(7):566, 2005. • Children cannot determine and communicate their own responses to drugs with reliable precision. • Parents frequently do not understand drug administration instructions. • Data are minimal about pediatric responses to medication. • Few clinical trials are used to support drug use for children, although the drugs are commonly used. • Pediatric dosage forms and packaging are not available in all drugs used for children. • Children have unpredictable disease states and organ responses to drugs. • Reactions in children may not reflect the responses exhibited by adults. • Be sure the pediatric patient’s weight is recorded in grams or kilograms (as appropriate for age and size) on the chart because weight-based dosages require accurate measurement for calculation. • Do not abbreviate dosages or volumes. • Clarify any questionable drug, dose, or route. • Check for allergies. Observe the pediatric patient for new signs of allergy if a new medication is added to the regimen. • When the drug is measured in decimals, be sure to use a zero at the left of the decimal to signify the fraction (e.g., 0.2 mg rather than .2 mg). Do not use a zero at the right of the decimal (e.g., 5 mg rather than 5.0 mg). Errors happen when someone does not see the decimal. • Use generic names of drugs as a routine. • Be sure to have clear signatures and contact numbers for the person prescribing the drug. • Avoid verbal orders if possible. • Know the medication and its actions before giving the drug. • Know the medication delivery devices before using them (e.g., infusion pumps). The following are general considerations: 1. Correction of a congenital anomaly as soon after birth as possible may be better psychologically for both the infant and the parents. The infant younger than 1 year does not remember the experience. Parents gain confidence in learning to cope with a residual deformity as the infant learns to compensate for it. Fear of body mutilation or punishment may be of paramount importance to a preschool or young school-age child. Children from 2 to 5 years of age have great sensitivity and a tenuous sense of reality. They live in a world of magic, monsters, and retribution, yet they are aggressive. School-age children have an enhanced sense of reality and value honesty and fairness. Their natural interest and curiosity aid communication. These children need reassurances and explanations in vocabulary compatible with their developmental level. Words should be chosen wisely. Negative connotations should be avoided, and the positive aspects should be stressed. The nurse should talk on the child’s level about his or her interests and concerns. Anxiety in the school-age child may be stimulated by remembrance of a previous experience. Many children undergo two or more staged surgical procedures before the deformity of a congenital anomaly or traumatic injury is cosmetically reconstructed or functionally restored. Familiarity with the nursing staff reassures the child. Ideally, the same circulating nurse who was present for the first surgical procedure should visit preoperatively and be with the child during subsequent surgical procedures. Fear of the unknown about general anesthesia may become exaggerated into extreme anxiety with fantasies of death. The school-age child and adolescent need facts and reassurances. General anesthesia should not be referred to as “putting you to sleep.” The child may equate this phrase with the euthanasia of a former pet that never returned home. Instead, the nurse should say, “You will sleep for a little while” or “You will take a nap.” Tell the child about the “nice nurses” who will be in the “wake-up room after your nap.” Parents should be encouraged to also display confidence and cheerfulness to avoid transmitting anxiety. Parents should be honest with their child but maintain a confident manner. The perioperative nurse should do the same. However, a school-age child should not be given information not asked for; questions should be answered, and misunderstandings should be corrected. The nurse should be especially alert to silent, stoic, noncommunicative children, many of whom have difficult induction and emergence from anesthesia. Children who have lost a sibling or friend to death often fear hospitalization.

Perioperative pediatrics

Indications for surgery

Congenital anomalies

Considerations in perioperative pediatrics

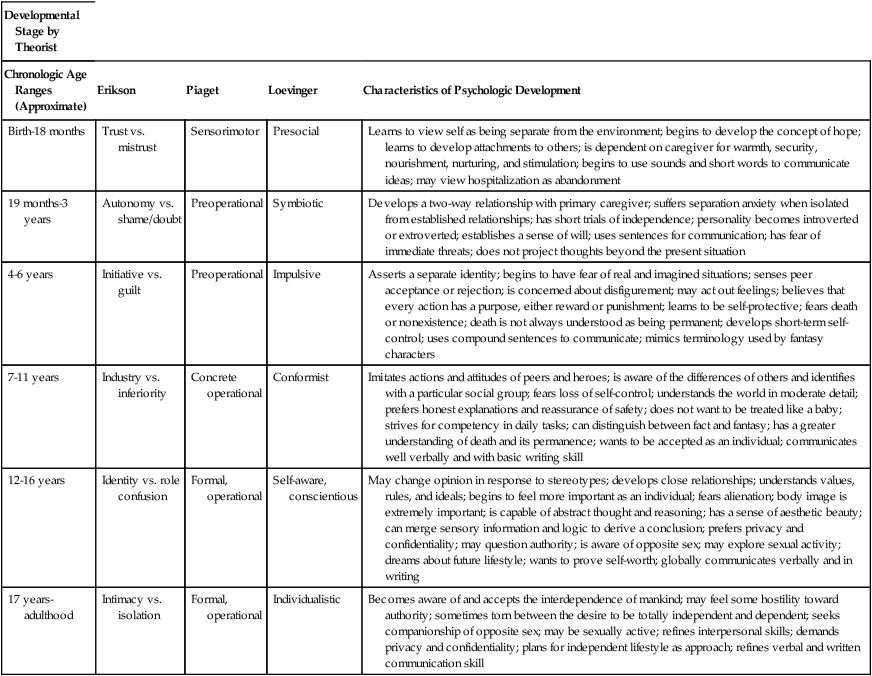

Developmental Stage by Theorist

Chronologic Age Ranges (Approximate)

Erikson

Piaget

Loevinger

Characteristics of Psychologic Development

Birth-18 months

Trust vs. mistrust

Sensorimotor

Presocial

Learns to view self as being separate from the environment; begins to develop the concept of hope; learns to develop attachments to others; is dependent on caregiver for warmth, security, nourishment, nurturing, and stimulation; begins to use sounds and short words to communicate ideas; may view hospitalization as abandonment

19 months-3 years

Autonomy vs. shame/doubt

Preoperational

Symbiotic

Develops a two-way relationship with primary caregiver; suffers separation anxiety when isolated from established relationships; has short trials of independence; personality becomes introverted or extroverted; establishes a sense of will; uses sentences for communication; has fear of immediate threats; does not project thoughts beyond the present situation

4-6 years

Initiative vs. guilt

Preoperational

Impulsive

Asserts a separate identity; begins to have fear of real and imagined situations; senses peer acceptance or rejection; is concerned about disfigurement; may act out feelings; believes that every action has a purpose, either reward or punishment; learns to be self-protective; fears death or nonexistence; death is not always understood as being permanent; develops short-term self-control; uses compound sentences to communicate; mimics terminology used by fantasy characters

7-11 years

Industry vs. inferiority

Concrete operational

Conformist

Imitates actions and attitudes of peers and heroes; is aware of the differences of others and identifies with a particular social group; fears loss of self-control; understands the world in moderate detail; prefers honest explanations and reassurance of safety; does not want to be treated like a baby; strives for competency in daily tasks; can distinguish between fact and fantasy; has a greater understanding of death and its permanence; wants to be accepted as an individual; communicates well verbally and with basic writing skill

12-16 years

Identity vs. role confusion

Formal, operational

Self-aware, conscientious

May change opinion in response to stereotypes; develops close relationships; understands values, rules, and ideals; begins to feel more important as an individual; fears alienation; body image is extremely important; is capable of abstract thought and reasoning; has a sense of aesthetic beauty; can merge sensory information and logic to derive a conclusion; prefers privacy and confidentiality; may question authority; is aware of opposite sex; may explore sexual activity; dreams about future lifestyle; wants to prove self-worth; globally communicates verbally and in writing

17 years-adulthood

Intimacy vs. isolation

Formal, operational

Individualistic

Becomes aware of and accepts the interdependence of mankind; may feel some hostility toward authority; sometimes torn between the desire to be totally independent and dependent; seeks companionship of opposite sex; may be sexually active; refines interpersonal skills; demands privacy and confidentiality; plans for independent lifestyle as approach; refines verbal and written communication skill

Chronologic age

Perioperative assessment of the pediatric patient

Pediatric psychosocial assessment

Pediatric physical assessment

Fluid and electrolyte balance considerations

Age

Hemoglobin (g/dL)

Hematocrit (%)

Leukocytes (mm3)

Platelets (mm3)

Cord blood

13.7-20.1

45-65

9000-30,000

350

2 weeks

13-20

42-46

5000-21,000

260

3 months

9.5-14.5

34-41

6000-18,000

250

6 months-6 years

10.5-14

33-42

6000-15,000

250

7-12 years

11-16

34-40

4500-13,500

250

Age

Blood Volume (mL/kg)

Neonate

75 to 80

6 weeks-2 years

75

2 years-puberty

72

Body temperature considerations

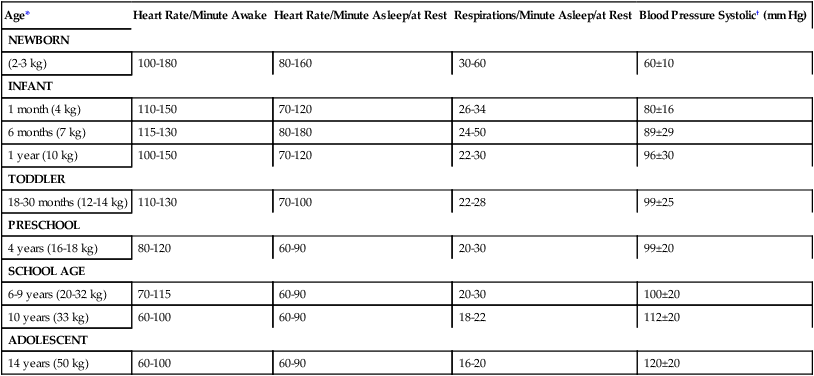

Cardiopulmonary status considerations

Age*

Heart Rate/Minute Awake

Heart Rate/Minute Asleep/at Rest

Respirations/Minute Asleep/at Rest

Blood Pressure Systolic† (mm Hg)

NEWBORN

(2-3 kg)

100-180

80-160

30-60

60±10

INFANT

1 month (4 kg)

110-150

70-120

26-34

80±16

6 months (7 kg)

115-130

80-180

24-50

89±29

1 year (10 kg)

100-150

70-120

22-30

96±30

TODDLER

18-30 months (12-14 kg)

110-130

70-100

22-28

99±25

PRESCHOOL

4 years (16-18 kg)

80-120

60-90

20-30

99±20

SCHOOL AGE

6-9 years (20-32 kg)

70-115

60-90

20-30

100±20

10 years (33 kg)

60-100

60-90

18-22

112±20

ADOLESCENT

14 years (50 kg)

60-100

60-90

16-20

120±20

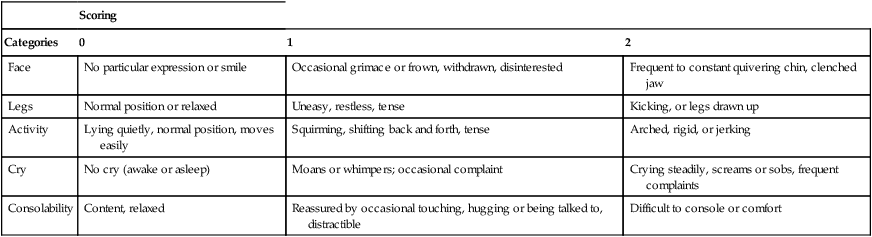

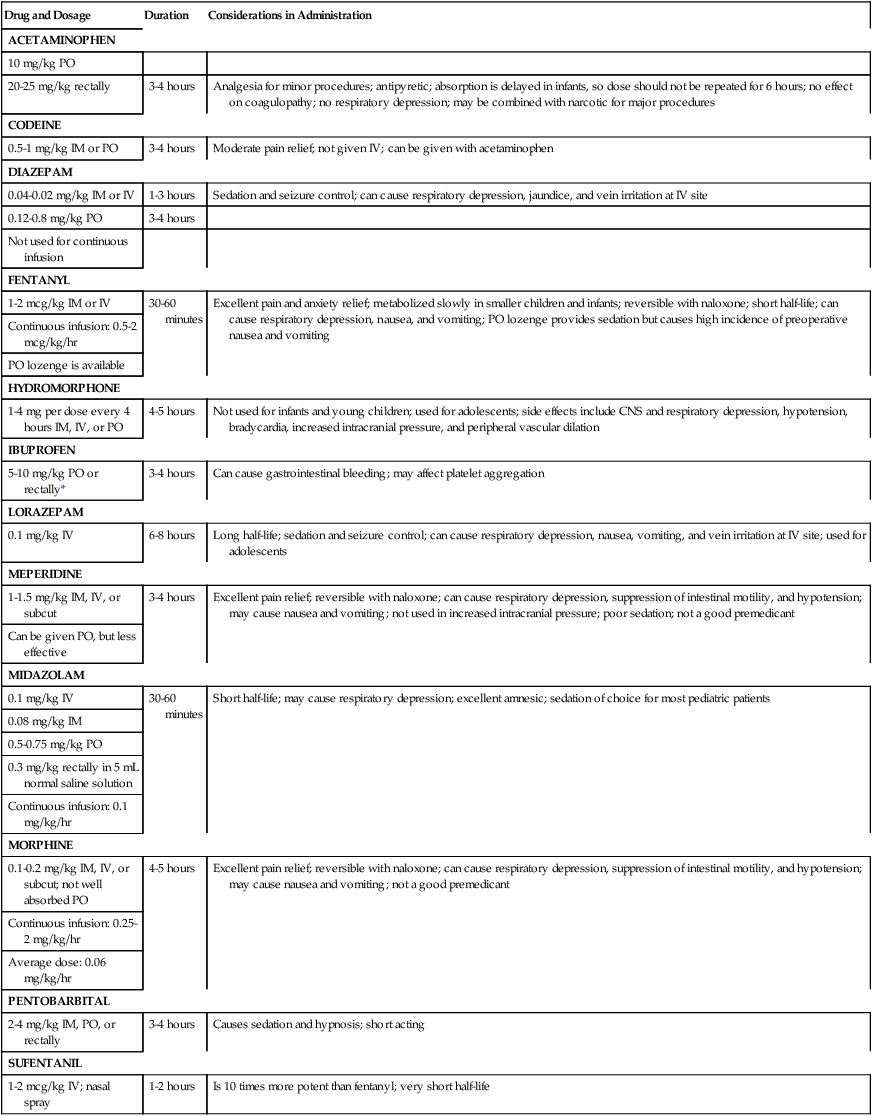

Pediatric pain management considerations

Scoring

Categories

0

1

2

Face

No particular expression or smile

Occasional grimace or frown, withdrawn, disinterested

Frequent to constant quivering chin, clenched jaw

Legs

Normal position or relaxed

Uneasy, restless, tense

Kicking, or legs drawn up

Activity

Lying quietly, normal position, moves easily

Squirming, shifting back and forth, tense

Arched, rigid, or jerking

Cry

No cry (awake or asleep)

Moans or whimpers; occasional complaint

Crying steadily, screams or sobs, frequent complaints

Consolability

Content, relaxed

Reassured by occasional touching, hugging or being talked to, distractible

Difficult to console or comfort

Drug and Dosage

Duration

Considerations in Administration

ACETAMINOPHEN

10 mg/kg PO

20-25 mg/kg rectally

3-4 hours

Analgesia for minor procedures; antipyretic; absorption is delayed in infants, so dose should not be repeated for 6 hours; no effect on coagulopathy; no respiratory depression; may be combined with narcotic for major procedures

CODEINE

0.5-1 mg/kg IM or PO

3-4 hours

Moderate pain relief; not given IV; can be given with acetaminophen

DIAZEPAM

0.04-0.02 mg/kg IM or IV

1-3 hours

Sedation and seizure control; can cause respiratory depression, jaundice, and vein irritation at IV site

0.12-0.8 mg/kg PO

3-4 hours

Not used for continuous infusion

FENTANYL

1-2 mcg/kg IM or IV

30-60 minutes

Excellent pain and anxiety relief; metabolized slowly in smaller children and infants; reversible with naloxone; short half-life; can cause respiratory depression, nausea, and vomiting; PO lozenge provides sedation but causes high incidence of preoperative nausea and vomiting

Continuous infusion: 0.5-2 mcg/kg/hr

PO lozenge is available

HYDROMORPHONE

1-4 mg per dose every 4 hours IM, IV, or PO

4-5 hours

Not used for infants and young children; used for adolescents; side effects include CNS and respiratory depression, hypotension, bradycardia, increased intracranial pressure, and peripheral vascular dilation

IBUPROFEN

5-10 mg/kg PO or rectally*

3-4 hours

Can cause gastrointestinal bleeding; may affect platelet aggregation

LORAZEPAM

0.1 mg/kg IV

6-8 hours

Long half-life; sedation and seizure control; can cause respiratory depression, nausea, vomiting, and vein irritation at IV site; used for adolescents

MEPERIDINE

1-1.5 mg/kg IM, IV, or subcut

3-4 hours

Excellent pain relief; reversible with naloxone; can cause respiratory depression, suppression of intestinal motility, and hypotension; may cause nausea and vomiting; not used in increased intracranial pressure; poor sedation; not a good premedicant

Can be given PO, but less effective

MIDAZOLAM

0.1 mg/kg IV

30-60 minutes

Short half-life; may cause respiratory depression; excellent amnesic; sedation of choice for most pediatric patients

0.08 mg/kg IM

0.5-0.75 mg/kg PO

0.3 mg/kg rectally in 5 mL normal saline solution

Continuous infusion: 0.1 mg/kg/hr

MORPHINE

0.1-0.2 mg/kg IM, IV, or subcut; not well absorbed PO

4-5 hours

Excellent pain relief; reversible with naloxone; can cause respiratory depression, suppression of intestinal motility, and hypotension; may cause nausea and vomiting; not a good premedicant

Continuous infusion: 0.25-2 mg/kg/hr

Average dose: 0.06 mg/kg/hr

PENTOBARBITAL

2-4 mg/kg IM, PO, or rectally

3-4 hours

Causes sedation and hypnosis; short acting

SUFENTANIL

1-2 mcg/kg IV; nasal spray

1-2 hours

Is 10 times more potent than fentanyl; very short half-life

Preoperative psychological preparation of pediatric patients

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Perioperative pediatrics

Website

Website