Patient Story

A 41-year-old man presents with a 4-month history of epigastric pain. The pain is dull, achy, and intermittent; there is no radiation of the pain and it has not changed in character since it began. Coffee intake seems to exacerbate the symptoms while eating or drinking milk helps. Infrequently, he is awakened at night from the pain. He reports no weight loss, vomiting, melena, or hematochezia. On examination, there is mild epigastric tenderness with no rebound or guarding. The reminder of the examination is unremarkable. A stool antigen test is positive for Helicobacter pylori, and the patient is treated for peptic ulcer disease with eradication therapy.

Introduction

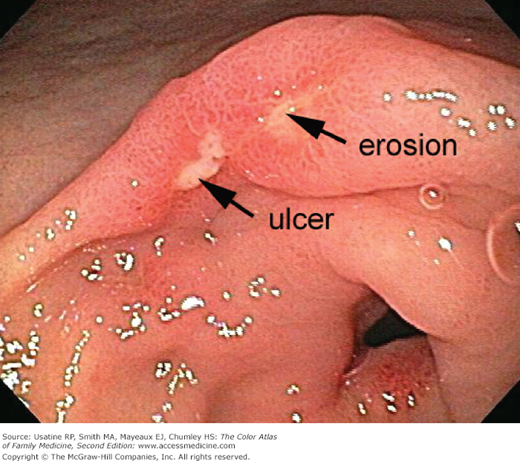

Peptic ulcer disease (PUD) is a disease of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract characterized by a break in the mucosal lining of the stomach or duodenum secondary to pepsin and gastric acid secretion, this damage is greater than 5 mm in size and with a depth reaching the submucosal layer.1

Epidemiology

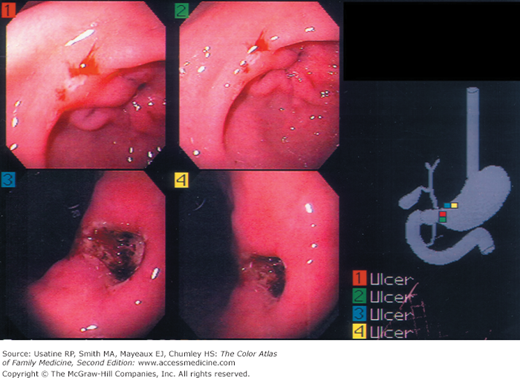

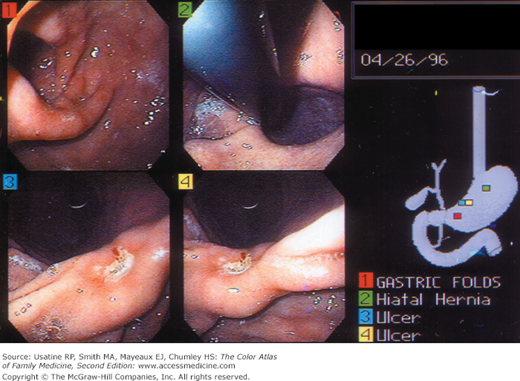

- PUD is a common disorder affecting approximately 4.5 million people annually in the United States. It encompasses both gastric and duodenal ulcers (Figures 59-1 and 59-2).2

- One-year point prevalence is 1.8%, and the lifetime prevalence is 10% in the United States.2

- Prevalence is similar in both sexes, with increased incidence with age.1 Duodenal ulcers most commonly occur in patients between the ages of 30 and 55 years, whereas gastric ulcers are more common in patients between the ages of 55 and 70 years.2

- PUD incidence in H. pylori-infected individuals is approximately 1% per year (6- to 10-fold higher than uninfected subjects).1

- Physician office visit and hospitalization for PUD have decreased in the last few decades.1

- The current U.S. annual direct and indirect health care costs of PUD are estimated at approximately $10 billion. However, the incidence of peptic ulcers keeps declining, possibly as a result of the increasing use of proton pump inhibitors and eradication of H. pylori infection.3

Etiology and Pathophysiology

- Causes of PUD include:

- NSAIDs, chronic H. pylori infection, and acid hypersecretory states such as Zollinger-Ellison syndrome.2

- Uncommon causes include Cytomegalovirus (especially in transplantation recipients), systemic mastocytosis, Crohn disease, lymphoma, and medications (e.g., alendronate).2

- Up to 10% of ulcers are idiopathic.2

- NSAIDs, chronic H. pylori infection, and acid hypersecretory states such as Zollinger-Ellison syndrome.2

- Infection with H. pylori, a short, spiral-shaped, microaerophilic Gram-negative bacillus, is the leading cause of PUD. It is associated with up to 70% to 80% of duodenal ulcers.2

- H. pylori colonize the deep layers of the gel that coats the mucosa and disrupt its protective properties causing release of certain enzymes and toxins. These make the underlying tissues more vulnerable to damage by digestive juices and thus cause injury to the stomach (Figures 59-1, 59-2, 59-3) and duodenum cells.1

- NSAIDs are the second most common cause of PUD and account for many H. pylori-negative cases.

- NSAIDs and aspirin inhibit mucosal cyclooxygenase activity reducing the level of mucosal prostaglandin causing defects in the protective mucous layer.

- There is a 10% to 20% prevalence of gastric ulcers and a 2% to 5% prevalence of duodenal ulcers in long-term NSAID users.2 The annual risk of a life-threatening ulcer-related complication is 1% to 4% in long-term NSAID users, with older patients having the highest risk.7

Risk Factors

- Severe physiologic stress—Burns, central nervous system trauma, surgery, and severe medical illness increase the risk for secondary (stress) ulceration.4

- Smoking—Evidence that tobacco use is a risk factor for duodenal ulcers in not conclusive, with several studies producing contradictory findings. However, smoking in the setting of H. pylori infection may increase the risk of relapse of PUD.5

- Alcohol use—Ethanol is known to cause gastric mucosal irritation and nonspecific gastritis. Evidence that consumption of alcohol is a risk factor for duodenal ulcer is inconclusive.5

- Medications—Corticosteroids alone do not increase the risk for PUD; however, they can potentiate ulcer risk in patients who use NSAIDs concurrently.4

Diagnosis

- Epigastric pain (dyspepsia), the hallmark of PUD, is present in 80% to 90% of patients; however, this symptom is not sensitive or specific enough to serve as a reliable diagnostic criterion for PUD. Pain is typically described as gnawing or burning, occurring 1 to 3 hours after meals and relieved by food or antacids. It can occur at night, and sometimes radiates to the back.2 Less than 25% of patients with dyspepsia have ulcer disease at endoscopy.4

- Other dyspeptic symptoms including belching, bloating, and distention are common but also not specific features of PUD as they are commonly encountered in many other conditions.

- Additional symptoms include fatty food intolerance, heartburn, and chest discomfort.

- Nausea and anorexia may occur with gastric ulcers.

- Significant vomiting and weight loss are unusual with uncomplicated ulcer disease and suggest gastric outlet obstruction or gastric malignancy.2

- Twenty percent of patients with ulcer complications such as bleeding and nearly 61% of patients with NSAID-related ulcer complications have no antecedent symptoms.

- Rare and nonspecific physical findings include:

- Epigastric tenderness.

- Heme-positive stool.

- Hematemesis or melena in cases of GI bleeding.

- Epigastric tenderness.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree