Pediatric Forensic Pathology

Jonathan Eisenstat, M.D.

INTRODUCTION

Forensic pathology is the field of medicine that deals with the investigation of death utilizing the scientific method as it pertains to the court of law. It is the study and investigation of bodily disease, injury, and death. Forensic pathologists are medical doctors who have completed at least an anatomic pathology residency and a forensic pathology fellowship. There are only approximately 500 board-certified forensic pathologists in the United States. Most often, the forensic pathologist is asked to determine the cause and manner of an individual’s death, although consults on live patients for wound interpretation do occasionally occur. The cause of death is essentially why the person died. The underlying cause of death is the etiologically specific disease or injury that, unbroken by any sufficient intervening cause, initiated the lethal sequence of events that led to the individual’s death. For example, if a child sustained a traumatic brain injury at the age of 1 year and survived for a period of time on a ventilator, subsequently developing pneumonia, and eventually succumbed to the pneumonia, the incident that started this chain of events was the head injury, and thus, it is considered the underlying cause of death. The immediate cause of death in this case would be the pneumonia. The manner of death reflects the circumstances under which the individual died. It is divided into five categories (six in some jurisdictions). According to the National Association of Medical Examiners Guide for Manner of Death Classification (1), the following are the accepted categories of manner of death: natural—due solely to a natural disease process or as a result of aging; accident— when an injury or poisoning causes death, without evidence of intent to harm; suicide—as a result of an intentional self-inflicted act; homicide—as a result of a volitional act committed by another person; and undetermined—when the manner could not be determined after a thorough investigation; and some have suggested a sixth manner as therapeutic complication/misadventure—this manner of death is utilized when an individual dies as a result of a known complication of a medical procedure (2). For instance, if a femoral line is placed in a patient and the patient develops a retroperitoneal hemorrhage resulting in death, this is a known complication of this procedure and should be classified as such. Deeming a manner of death to be a therapeutic complication/misadventure is a nonjudgmental determination that takes the burden away from the pathologist of having to decide if this should be called a natural death or an accident. It is not synonymous with negligence or malpractice. Pediatric deaths can fall into any of these categories. As of 2010, the National Vital Statistics System of the CDC (3) showed that the most common manner of death in children less than 1 year old was natural, mostly due to congenital anomalies. If congenital anomalies and short gestation, which mainly cause death in the first month of life, were to be removed, sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) would be the most prevalent cause of death in the first year of life. Unintentional injuries were the leading cause of death between the ages of 1 and 44 years. These accidental deaths include motor vehicle accidents, drug intoxications, and asphyxial deaths such as drowning or choking, to mention a few. Suicides and homicides become more prevalent with increasing age.

The medicolegal death investigation system varies throughout the United States. Some states are strictly medical examiner systems, some are coroner systems, and others are a combination of coroner and medical examiner. As described above, medical examiners are medical doctors trained in the investigation of death. Coroners may be physicians but are usually lay individuals who are locally elected officials. They can have varying levels of medical knowledge and education, from a high school degree to a doctorate. They most often are elected by the citizens of a particular county and are responsible for receiving death calls, responding to certain scenes and pronouncing death in certain circumstances. They are also the individuals who sign the death certificates of unattended or traumatic deaths that occur in their jurisdiction. The coroner often consults with the medical examiner concerning the cause and manner of a person’s death. The weakest link of the coronial system is the potential difference between what the medical examiner determines the cause and manner of death to be and what the coroner decides (4). The majority of forensic pathologists practicing in the United States do so in a medical examiner setting, whether or not

the overall system is a coroner system. Sixty-five percent of the 3145 county-equivalent jurisdictions in the United States have coroners as their chief medicolegal officers (5).

the overall system is a coroner system. Sixty-five percent of the 3145 county-equivalent jurisdictions in the United States have coroners as their chief medicolegal officers (5).

Different jurisdictions have different laws concerning what types of cases fall under the purview of the medical examiner. In general, any death of a non-terminally ill child, where there is a traumatic injury or the death is unwitnessed, should at a minimum be referred to the medical examiner and/or coroner. The medical examiner office will then decide if the case warrants an examination by the forensic pathologist. All homicides, no matter how delayed the death is, warrants an exam by the medical examiner office. Other traumatic cases may be taken on a case-by-case basis depending on the level of suspicion and concern by law enforcement, the prosecutor’s office, and other public officials. If a child has a natural disease where the death is expected, depending on the circumstances surrounding the death, the medical examiner may decline jurisdiction.

Child fatality review committees meet on a regular basis to review child death cases. They are composed of representatives from different agencies. Child advocates, pediatricians, law enforcement, district attorneys, and medical examiners partake in these meetings. The aim of the child fatality review is to identify possible deficiencies within the system and attempt to correct them as well as identify any trends that may be occurring.

FORENSIC AUTOPSY

The forensic autopsy, as with the hospital autopsy, is performed to determine the child’s cause of death. In the hospital setting, the natural disease process is the main focus of the examination. In the forensic setting, any natural disease should be documented, but there are a number of other questions that need to be answered and specimens that should be procured. These include interpretation of injuries, determining the manner of the child’s death, collection of biologic specimens for a multitude of ancillary studies, collection of trace evidence (hair and fibers), and sometimes identifying the child. The questions that need to be answered are not only medical but also of a legal nature.

External Examination

The autopsy begins with an external examination. The first external procedure that should be performed is the taking of photographs of the body as it is received in the morgue, prior to any manipulation of the body. This will allow for documentation of any articles of clothing, personal effects, injuries, and medical intervention. The clothing, personal effects, and therapeutic devices should then be removed, and the body should be photographed naked. All clothing and personal effects received with the body should be documented and, if deemed necessary, retained as evidence. Clothing is usually retained only in homicide cases. A head-to-toe evaluation should then take place with documentation of all natural and traumatic findings. This includes looking in the oral cavity, ears, female external genitalia, and anus. If the child is an uncircumcised male, the foreskin should be retracted and examined. The standard measurements (crown-heel, crown-rump, head circumference, chest circumference, abdominal circumference, foot length) should be taken and compared to standard growth charts. As the external examination is proceeding, any finding with potential evidentiary value should be retained, including trace evidence such as fibers and hairs that appear to be other than those from the child. When child abuse is suspected, scalp hair from the child should be taken and retained. This can become important if the scene reveals an impact site on a wall or other surface, where hair may be present. The decedent’s hair that was pulled at autopsy can be compared with that found at the scene. All of this needs to be done maintaining appropriate chain of custody and documentation. When documenting a significant injury, the location on the body should be described in relation to a standard anatomical landmark. The most common landmarks used are the head, feet, shoulder, and midline of the torso. For example, an injury may be located 12 cm below the top of the head and 1 cm left of the midline. This may be important when different scenarios are given in an attempt to explain the causation of the injury. Correlation between the different scenarios and the location of the injuries on the child’s body may prove or disprove one or all of the histories presented. Diagrams should be available and used if necessary as they may become extremely valuable in trying to convey your findings to a family or jury.

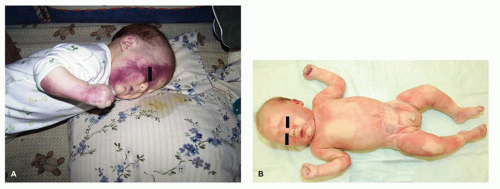

When examining a body, both at the scene and in the autopsy suite, documentation of postmortem changes is important. These changes should be conveyed through pictures as they may have progressed from the time the body is examined at the place of death to the time of autopsy. The standard postmortem changes that are usually documented (rigor mortis, livor mortis, algor mortis, and decomposition) have been studied in adults; thus, in children, the timing of these changes may be different than is stated below. We know that children have a lower muscle mass than do adults and lose heat at a quicker rate, both of which play a role in the rate of postmortem change. Rigor mortis is the stiffening of the body. It is the result of cross-linking of actin and myosin to form actinomyosin as the level of ATP decreases. In general, this process begins within 2 to 6 hours after death and starts in the smaller muscle groups first (6). By 12 hours, rigor is usually fully formed and stays as such for another 12 hours before it begins to fade. Livor mortis is the settling of the blood via gravity after circulation ceases. Lividity appears within 30 minutes after death and will become “fixed” after about 12 hours. Prior to becoming fixed, the blood will move with gravity as the body is moved. Once fixed, no matter how the body is moved, lividity will not follow gravitational pull and will remain in the same anatomic location. This is why photographs of the child at the scene are extremely important; it may be the only time you can see the true lividity pattern, which correlates with the position of the child when found (Figure 7-1). Algor mortis is the change

in body temperature after death. Variables that need to be considered when evaluating algor mortis are the decedent’s antemortem temperature (did he or she have a fever?) and the temperature and humidity of the environment where the body was found. Certain drugs may increase an individual’s temperature as well, such as cocaine and methamphetamine. Once the individual dies, the body temperature will start to equilibrate with the ambient temperature. Algor mortis is not a very reliable marker for determining the time since death. Decomposition consists of autolysis, putrefaction, and mummification. Autolysis is the result of internal cell breakdown due to the body’s innate enzymes, commonly seen in the pancreas. Putrefaction is the result of bacteria and fungi spreading throughout the body. These organisms degrade the tissues resulting in gaseous by-products that lead to the foul odor associated with decomposition, softening of the organs, and microscopic bubbles seen on histologic analysis. Mummification is the drying out of the tissues secondary to an arid environment. If a stillborn fetus is being evaluated, the postmortem changes are the result of maceration. Maceration is due to the fetus floating in a pool of amniotic fluid with resultant skin changes such as erythema and sloughing, brown-red discoloration starting at the umbilical stump, liquefaction of internal organs, and microscopic loss of nuclear basophilia of the tubular cells of the renal cortex (Figure 7-2). Nonfetal bodies that are found in environments containing moisture can result in adipocere, a waxy substance produced by hydrolysis and hydrogenation of body fat, usually as a result of Clostridium perfringens. Other postmortem changes that may occur and should be documented include insect activity and animal predation. In certain cases, evaluation of the insects can be performed by an entomologist, and an opinion can be rendered concerning how long the child has been dead.

in body temperature after death. Variables that need to be considered when evaluating algor mortis are the decedent’s antemortem temperature (did he or she have a fever?) and the temperature and humidity of the environment where the body was found. Certain drugs may increase an individual’s temperature as well, such as cocaine and methamphetamine. Once the individual dies, the body temperature will start to equilibrate with the ambient temperature. Algor mortis is not a very reliable marker for determining the time since death. Decomposition consists of autolysis, putrefaction, and mummification. Autolysis is the result of internal cell breakdown due to the body’s innate enzymes, commonly seen in the pancreas. Putrefaction is the result of bacteria and fungi spreading throughout the body. These organisms degrade the tissues resulting in gaseous by-products that lead to the foul odor associated with decomposition, softening of the organs, and microscopic bubbles seen on histologic analysis. Mummification is the drying out of the tissues secondary to an arid environment. If a stillborn fetus is being evaluated, the postmortem changes are the result of maceration. Maceration is due to the fetus floating in a pool of amniotic fluid with resultant skin changes such as erythema and sloughing, brown-red discoloration starting at the umbilical stump, liquefaction of internal organs, and microscopic loss of nuclear basophilia of the tubular cells of the renal cortex (Figure 7-2). Nonfetal bodies that are found in environments containing moisture can result in adipocere, a waxy substance produced by hydrolysis and hydrogenation of body fat, usually as a result of Clostridium perfringens. Other postmortem changes that may occur and should be documented include insect activity and animal predation. In certain cases, evaluation of the insects can be performed by an entomologist, and an opinion can be rendered concerning how long the child has been dead.

FIGURE 7-1 • A: Photograph at scene showing lividity on the anterior surface of the body. B: Photograph at autopsy showing the lividity on the face much less recognizable. |

After the initial assessment, photographs, and external examination have been completed, any injuries, or suspected injuries, should be thoroughly documented. They should be described, measured, and photographed with a ruler and case identifier. If the injury is suggestive of a bite mark, an L-shaped ruler should be used in the photograph. After all of the injuries have been documented, punch biopsies can be taken and processed for histologic analysis. More specific details of various injuries are described below.

The internal examination starts with a “Y”-shaped incision. Documentation of any subcutaneous soft tissue injuries should be documented and photographed. If there is any abnormal fluid accumulation in any of the cavities, it should be measured and described. The chest plate will then be removed after documenting any fractures that may be present. The internal organs should be examined in situ to assess for any injury, malformation, or natural disease process. Internal body fluids, such as blood (if unable to be obtained externally) and urine, should be collected at this time and placed into the correct tube to be sent for analysis. Bile and blood should be collected and placed on specifically designed cards for metabolic and biologic studies. In infants, it is recommended to remove all of the organs en bloc as this allows for a better evaluation of the interconnections

between the organs and vasculature. The pleura should be stripped to allow for direct visualization of the ribs, and if any abnormality is identified, that portion of the rib should be removed. A radiograph of that specimen can be taken prior to decalcification, dissection, and histologic evaluation. If injuries are identified, or there is the suspicion of abuse, a posterior dissection of the neck, back, and all four extremities should be performed (Figure 7-3). This allows for evaluation of the soft tissues as well as direct visualization of the posterior aspect of the vertebrae and the long bones of the extremities. All of these steps need to be performed because skeletal injuries in children are often beyond the scope of the standard autopsy and radiology (7,8,9). In 2009, Love and Sanchez introduced a new technique, the pediatric skeletal examination (PSE) (10), to evaluate fractures in suspected child abuse cases. This is a fairly labor-intensive and time-consuming procedure that involves dissection down to the bone to allow for direct visualization of fractures. Love et al. (11) reviewed 94 cases of suspected inflicted trauma, half of which utilized the PSE and half of which did not. They showed that more fractures were identified with the PSE than without and determined that it was a valuable tool.

between the organs and vasculature. The pleura should be stripped to allow for direct visualization of the ribs, and if any abnormality is identified, that portion of the rib should be removed. A radiograph of that specimen can be taken prior to decalcification, dissection, and histologic evaluation. If injuries are identified, or there is the suspicion of abuse, a posterior dissection of the neck, back, and all four extremities should be performed (Figure 7-3). This allows for evaluation of the soft tissues as well as direct visualization of the posterior aspect of the vertebrae and the long bones of the extremities. All of these steps need to be performed because skeletal injuries in children are often beyond the scope of the standard autopsy and radiology (7,8,9). In 2009, Love and Sanchez introduced a new technique, the pediatric skeletal examination (PSE) (10), to evaluate fractures in suspected child abuse cases. This is a fairly labor-intensive and time-consuming procedure that involves dissection down to the bone to allow for direct visualization of fractures. Love et al. (11) reviewed 94 cases of suspected inflicted trauma, half of which utilized the PSE and half of which did not. They showed that more fractures were identified with the PSE than without and determined that it was a valuable tool.

FIGURE 7-2 • Macerated fetus showing erythema and skin sloughing. This is indicative of a death in utero, thus ruling out a live birth. |

FIGURE 7-3 • Posterior dissection of an infant to evaluate for trauma. The posterior neck, back, and all four extremities are dissected into the soft tissues to look for hemorrhage. |

The autopsy is only one of the many tools utilized by the forensic pathologist in formulating his or her conclusions. Some of the other methodologies available to the forensic pathologist include radiology, photography (both antemortem and postmortem), metabolic analysis, toxicology, vitreous chemical analysis, microbiology, odontology, anthropology, trace evidence, ballistics, and biology (DNA). Depending on the case, any combination of the above ancillary studies may be utilized; in addition to investigation, which should be performed in every case.

Radiology

Every infant who presents for autopsy, as well as any child or adolescent with penetrating injury or suspected abuse, should undergo skeletal radiography. In infants, the entire skeleton should be x-rayed, whether it be a digital skeletal survey, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, or multiple individual films that reveal the entire skeleton. A single plain film “babygram” is discouraged as the most common of inflicted skeletal injuries are often missed with these types of films. Radiology is extremely important as certain types of fractures, such as classic metaphyseal lesions diagnostic of nonaccidental trauma, may be better visualized radiographically (12). If fractures are identified during the autopsy, they can be dissected, removed, and reimaged for better definition.

Photography

Photography is an extremely important ancillary study. Overall photographs of the body as it is received in the morgue should be taken prior to removal of clothing, personal effects, and therapeutic devices. Photographs of the body naked, both front and back, should then be taken. All injuries should be photographically documented. Sometimes, photographs of the child in life can be compared to postmortem photographs to highlight similarities or differences. These photographs may be used in a court of law to portray injuries or a lack thereof.

Metabolic Analysis

Metabolic studies can be requested on either blood or bile stain cards to test for the more common metabolic disorders. The CDC, Office of the Chief Medical Examiner in Virginia, and a private laboratory conducted a population-based study of all child deaths under 3 years of age from 1996 to 2001 and revealed that 1% of these children had a positive metabolic screen using tandem mass spectrometry. Not only does this help identify the cause of the child’s death but also it may prevent a false determination of child maltreatment as well as help prevent a subsequent death of one of the child’s siblings (13).

Toxicology

Toxicology should be performed on all cases. This is to rule out both accidental and intentional intoxications. Certain drugs can be found in breast milk, while other drugs can be transferred to the child via transdermal patches. Some parents have been known to hide drugs in their child’s diapers, while some children have found their way into their parent’s prescription and/or illicit drugs. Gray top tubes contain potassium oxalate, which is an anticoagulant, and sodium fluoride, a cholinesterase inhibitor. These tubes should be used when submitting blood for toxicologic analysis as they will help prevent degradation of certain drugs (14).

Chemistry

Vitreous humor is the best postmortem biologic specimen to use for the analysis of electrolytes and glucose. It should be aspirated only after a negative internal evaluation of the retrobulbar soft tissues and perioptic nerve sheaths. Dehydration patterns and diabetes mellitus can be diagnosed using this specimen. The procedure of withdrawing vitreous humor involves inserting a 20-gauge needle attached to a 6- or 10-mL syringe into the globe just anterior to the lateral canthus. After puncturing the globe, slight pressure should be used to aspirate the gelatinous fluid, being careful not to go too deep or use too much force, as the retina may be damaged making analysis unreliable. Only clear fluid should

be sent for testing as the contamination by blood or tissue will alter the results.

be sent for testing as the contamination by blood or tissue will alter the results.

Cultures

Infectious diseases are one of the most important public health concerns; thus, cultures should be considered in all autopsies. However, there are many who believe that postmortem cultures are of minimal or no value. Issues that arise when considering the value of postmortem cultures include contamination and postmortem spread of organisms. Essentially, bacteria in deceased individuals are similar to those in a laboratory culture as they can spread without any resistance from antibodies. Most contaminated specimens grow multiple organisms, whereas a single organism should arouse suspicion of a true infection. Even with a “positive” culture, it is of vital importance to perform microscopic analysis of the tissues in an attempt to determine if these positive cultures are the result of a true infection or the result of postmortem overgrowth. If organisms are seen microscopically, the presence or absence of inflammation will help make the determination if the bacteria are due to postmortem overgrowth or a true antemortem infection. Once the body is opened, there is rapid contamination of the surfaces of the internal organs from fluids that have now been exposed to external organisms; thus, a sterile technique is needed. When procuring a culture of an internal organ, the prosector must first sear the surface of that organ to sterilize it. This can be accomplished by taking a scalpel blade or spatula, heating it with a flame, and touching the surface of the organ until it is dried and black or white from the burn. Utilizing a sterile blade, a puncture of that organ should be performed through the burned surface and a culture swab placed through that opening. If any bodily fluid enters that site, it is deemed contaminated. This should all be done before removal of any organ. Another factor in deciding if blood cultures should be performed relies on the circumstances of the case. Cultures in the majority of postmortem examinations rarely reveal significant new information; thus, it may be difficult to justify the cost of the test (15). In addition, the amount of blood that is often obtained at postmortem examination in children is minimal, and decisions must be made how that blood is best utilized (cultures, toxicology, metabolic analysis, etc.). The procedure to aspirate cerebrospinal fluid for viral and/or microbiologic studies should be performed in the same fashion as a clinical spinal tap would be done. Swab the skin with alcohol or Betadine, use a sterile needle to enter the interspinous space, and aspirate. As multiple attempts may be necessary, it is recommended to start caudally with each reattempt moving cranially. This is to prevent migration of blood into the specimen. Other options are aspirating CSF through the foramen magnum or ventricles (15).

Odontology and Anthropology

Odontology and anthropology consultation can be used on an “as-needed” basis. Odontology can be used for identification purposes via comparison with antenatal dental films, which is rare in infants but may become more prevalent in the teenage years. Dental cavities and fillings can be used for comparison as well. Evaluating the eruption pattern of the teeth may assist in aging of the individual. Anthropology is a valuable resource for a number of reasons. A forensic anthropologist can help with the identification of a person, as well as perform trauma analysis on skeletal remains. They can measure certain bones and compare them to a standardized chart as well as inspect ossification zones to estimate the age the child was when he/she died.

Scene Investigation

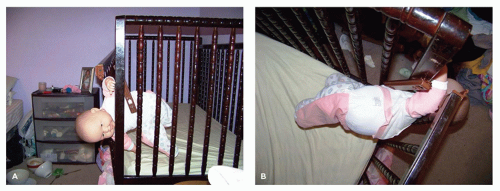

Scene investigation is an extremely important component of death investigation, and in certain cases, it may be the most critical. It may be performed in the presence of, or by, law enforcement, the coroner, and/or the medical examiner. Photographs should be taken of every scene as it may be the only time you will be able to see the site of the incident and/or death undisturbed, as it was when the individual died. Photographs should include the overall view of the scene and continue progressively closer until the exact location of death is found. The child should be photographed where found, both front and back, as progression of postmortem changes may occur between the time of the scene investigation and the time of the autopsy. This is well known with lividity, which may appear on the posterior aspect of the child’s body by the time of autopsy but was anteriorly distributed at the scene, indicating a prone position and possible asphyxia. Interviews should be performed at the initial scene visit. These interviews should be taken from the caregivers, others in the residence at the time of the death, and neighbors. These individuals should be interviewed separately to see if all of their stories coincide. Interviews may be performed a second time, if necessary. The overall surroundings should be assessed, that is, cleanliness of the residence, appearance of other children, food in the refrigerator, appropriateness of toys for the child’s age, animals, infestation, weapons, medications/drugs, and child’s sleeping environment, to name a few. A doll reenactment (in the case of an infant sleep-related death) can aid in the assessment of the child’s position when laid down to sleep and when found, including the surroundings, and in injury related deaths to allow the caregiver to show his/her version of how the injury may have occurred. If available, a buckwheat doll without any specific anatomical features should be used. An “F” can be written on the front and a “B” can be written on the back (Figure 7-4). The doll should be given to the individual who found the child, and he or she should be asked to show exactly what position the child was in when found. This should be photographed and/or videotaped. Any potential evidence should be procured and brought with the body to the autopsy. Many times, the body has been removed from the scene, either by emergency medical personnel or by personal vehicle. This does not negate the importance of a scene investigation. An investigator should be sent to the location where the child was found to perform a thorough investigation despite the fact that the scene may have been altered. The body should be photographed in the hospital, if that is where the child

was taken. If there are patterned injuries to the body, look throughout the residence for implements that may have been used, and submit those to the medical examiner office for evaluation. All of the information that has been gleaned from the scene investigation will be evaluated in conjunction with the autopsy findings to determine the cause and manner of death.

was taken. If there are patterned injuries to the body, look throughout the residence for implements that may have been used, and submit those to the medical examiner office for evaluation. All of the information that has been gleaned from the scene investigation will be evaluated in conjunction with the autopsy findings to determine the cause and manner of death.

Medical devices used in resuscitation should be left in place and documented to prevent any misinterpretation of findings at autopsy. As in any hospital autopsy, the medical history is of great importance. Medical records, including, but not limited to, birth records, pediatrician records, reports of emergency medical services, and records from the emergency department from the final admission, should be requested and reviewed. It is important to remember that just because a child has a significant medical history, it does not mean that he or she can’t die an unnatural death.

An important topic that the forensic pathologist is confronted with is organ donation. In most jurisdictions, the organ procurement agency consults with the medical examiner before proceeding with harvesting on cases that fall under the medical examiner’s jurisdiction. In addition to solid organ donation, the eyes, skin, long bones, and heart for heart valves may be procured. This is a very important and potentially lifesaving procedure that needs to be approached in a delicate manner. One needs to carefully weigh the potential benefits of donation to live patients while not disrupting any evidence that may affect the determination of cause and manner of death and possible litigation. Child abuse deaths are the cases that are most often denied donation due to the potential for disrupting evidence on the skin and within the body cavities. A major concern is the alteration of rib fractures, whether acute or remote, and the possibility of causing a posterior rib fracture as a result of a thoracotomy for harvesting the heart or lungs. One method for harvesting of the heart and/or lungs that has been proposed is a modified thoracotomy technique where an autopsy-type incision is made into the skin and the chest is opened through serial incisions of the anterior cartilaginous segments of the ribs. This prevents any strain being placed on the ribs that may result in alterations of fractures (16). Rarely, organ procurement will proceed despite objection from the medical examiner. This may result in an undetermined cause and manner of death as well as animosity between agencies (17). The best way to prevent a situation such as this is to have open and good communication with your local organ donation group. Part of the communication necessary to maintain a good working relationship between the autopsy pathologist and the organ procurement organizations includes the sharing of findings from the procuring institution, autopsy findings, and laboratory results. Photographs can be taken prior to, and during, the procurement. The organ and tissue procurement agencies are required to perform a number of tests to make sure that what they are transplanting is safe for the recipient. The results of these tests can and should be shared with the medical examiner and may aid in determining the cause and manner of the child’s death. One must remember that you have a responsibility not only to those requiring organs but also to the families of the deceased individual as well as the deceased himself/herself.

SUDDEN DEATH

In the pediatric forensic setting, the most common presentation of death will be that of a sudden unexplained death, most often in infancy. Approximately 4000 infants die suddenly and unexpectedly each year in the United States without any prior medical history (18). These deaths are most often determined to be due to SIDS, sudden unexplained infant death (SUID, a.k.a. sudden unexplained death in infancy, SUDI), or asphyxia. Epidemiologically, SUID and

SUDI are all coded with the same ICD code as SIDS deaths. The basic difference between these three categories includes sleep environment and evidence, or lack thereof, of asphyxia at the scene and/or autopsy. An analysis of 3136 sleep-related sudden unexpected infant deaths revealed that 24% were sleeping in a crib or on their back when found, 70% were on a sleep surface other than a recommended crib or bassinet, 64% were found on their side or stomach, and 49% were sleeping with an adult (19). The differences in certification of these types of deaths are discussed below. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has issued a standardized SUID investigation checklist available to any agency wishing to utilize it for child death investigation (20).

SUDI are all coded with the same ICD code as SIDS deaths. The basic difference between these three categories includes sleep environment and evidence, or lack thereof, of asphyxia at the scene and/or autopsy. An analysis of 3136 sleep-related sudden unexpected infant deaths revealed that 24% were sleeping in a crib or on their back when found, 70% were on a sleep surface other than a recommended crib or bassinet, 64% were found on their side or stomach, and 49% were sleeping with an adult (19). The differences in certification of these types of deaths are discussed below. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has issued a standardized SUID investigation checklist available to any agency wishing to utilize it for child death investigation (20).

Sturner outlined common errors in forensic pediatric pathology that highlight the necessity of much of what has been described above (21). The ten categories of errors that he highlighted include an incomplete or absent scene investigation, including the “bed of death” and environmental analysis such as temperature; inadequate or insufficient photography, including the position of the child when found and videography if necessary; improper postmortem interval assessment, such as forgetting that rigidity can become complete within a few hours and body temperature equilibrates within its surroundings quickly, especially in children; inadequate or incomplete medical records, including birth records; incomplete preautopsy study, such as body measurements; inadequate gross autopsy examination, such as forgetting to evaluate the gastrointestinal tract; incomplete microscopic examination, forgetting to examine all organs under the microscope; incomplete laboratory studies, such as toxicology and metabolic analysis; failure to differentiate and document artifacts, such as distinguishing antemortem from postmortem changes; and failure to give appropriate importance and significance to findings, such as how much alveolar acute inflammation constitutes a significant pneumonia (21).

Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS)

The term SIDS was initially coined in 1969 to define any unexpected death of an infant or young child that remained unexplained after a thorough investigation, including autopsy. It is essentially a diagnosis of exclusion. Currently, to determine that a death is due to SIDS, one has to adhere to a strict guideline, which includes a child between the age of 1 month and 1 year, without any pre-existing conditions including prematurity, and being found supine on an appropriate sleep surface without anything that could compromise the child’s ability to breathe. The diagnosis cannot be made until a complete autopsy has been performed, including toxicology, histology, metabolic analysis, review of medical records, and a thorough scene investigation. If no other potential or actual etiologically specific pathology is found, the cause of death can be deemed SIDS. The rate of SIDS has decreased dramatically over the years. The reason for the decreased incidence is twofold: (a) the back to sleep campaign, and (b) the change in the definition of SIDS. In 1994, the National Institute of Child Health and Development initiated the Back to Sleep campaign. Over the following 10 years, the rate of SIDS deaths decreased by greater than 50%, decreasing from 1.34 per 1000 live births to 0.64 per 1000 births (22). A number of risk factors for SIDS have been identified such as male sex, black race, and winter months. Most cases of SIDS occur before 6 months of age, usually between 2 and 4 months of age. A meta-analysis of 35 case control studies revealed that both prenatal and postnatal maternal smoking was associated with an increased risk of SIDS (23). This was dose dependent and suggested that maternal cessation of smoking may be protective against SIDS. Another meta-analysis, this time on 18 studies, showed that breastfeeding of any extent and duration was protective against SIDS, possibly as a result of its immunologic benefits (24,25). There is a divide between medical examiners as to the manner of death in SIDS cases, whether it be natural or undetermined. Many believe that all external factors have been ruled out and thus it is a natural death, whereas others believe that we still do not know why the child died and thus it deserves an undetermined manner. The autopsy in these cases is essentially negative, thus ruling out any obvious natural disease or traumatic injury. A common finding at autopsy is the presence of petechiae on the serosal surfaces of the thymus, lungs, and heart. These are nonspecific findings, which can be seen in other causes, such as asphyxia. Microscopically, these petechiae may be seen, as well as pulmonary edema, congestion, and slight hemorrhage. Recent research has focused on morphologic differences in the brainstems of children who have died of SIDS suggesting that these cases may be due to immature development of the centers responsible for arousal, cardiovascular, and respiratory functions. When these children are faced with an environmental stressor, they are vulnerable to sudden death. This has led to the triple risk model: underlying vulnerability, critical stage of development (peak between 2 and 4 months of postnatal life), and an exogenous stressor (26,27). Intrinsic and extrinsic risk factors have been identified. The intrinsic risk factors include African American race, male gender, prematurity, and prenatal maternal smoking or alcohol use, whereas extrinsic risk factors include any physical stressor present around the time of death such as prone or side sleep, bed sharing, over bundling, soft bedding, or the child’s face being covered (26). Ninety-nine percent of SIDS infants had at least 1 intrinsic or extrinsic risk factor, and 75% had at least 1 of each (26). As will be described below, a diagnostic shift has taken a number of these extrinsic factors and changed the terminology from SIDS to SUID (sudden unexplained infant death) (27). There is an adage that the first unexpected death of a child in a family may be SIDS, a subsequent death may be deemed undetermined, and a third death is a homicide until proven otherwise.

Recent studies have highlighted the prevalence of cardiac channelopathies in sudden infant deaths. Some of the more well-known disorders that are identified in sudden death in young individuals are long QT syndrome, Brugada syndrome, short QT syndrome, and catecholaminergic polymorphic

ventricular tachycardia. Long QT syndrome has a prevalence of 1 in 2500 and is currently known to involve over 700 mutations in 12 genes (28). Mutations in repolarizing cardiac potassium channels KCNQ1/Kv7.1 (LQT1) and hERG1/Kv11.1 (LQT2) are the most common and predispose the individual to ventricular arrhythmias, syncope, and sudden cardiac death (29). Schwartz et al. identified that 50% of a cohort of SIDS deaths had a prolongation of the corrected QT interval and that if there was the presence of a prolonged corrected QT interval in the first week of life, it imparted a 41.6 times increased risk of SIDS (30). The other disorders mentioned have varying mutations and lethality but usually present with the same symptoms. The above-mentioned known channelopathies are seen in SIDS cases but research on children who have died of SIDS shows that the majority of the channelopathies in these deaths are related to mutations in the sodium channels (29). The importance of identifying a channelopathy as the cause of death is not only to help the family come to an understanding of why their child died but to alert the family to the possibility of a sibling having the same mutation and to refer him or her for evaluation. Other genetic abnormalities have been found in infants who die suddenly and unexpectedly, such as medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (MCAD) deficiency, which is the most common inherited disorder of fatty acid metabolism, which presents in early childhood with a potentially fatal episode of hypoketotic hypoglycemic crisis (28).

ventricular tachycardia. Long QT syndrome has a prevalence of 1 in 2500 and is currently known to involve over 700 mutations in 12 genes (28). Mutations in repolarizing cardiac potassium channels KCNQ1/Kv7.1 (LQT1) and hERG1/Kv11.1 (LQT2) are the most common and predispose the individual to ventricular arrhythmias, syncope, and sudden cardiac death (29). Schwartz et al. identified that 50% of a cohort of SIDS deaths had a prolongation of the corrected QT interval and that if there was the presence of a prolonged corrected QT interval in the first week of life, it imparted a 41.6 times increased risk of SIDS (30). The other disorders mentioned have varying mutations and lethality but usually present with the same symptoms. The above-mentioned known channelopathies are seen in SIDS cases but research on children who have died of SIDS shows that the majority of the channelopathies in these deaths are related to mutations in the sodium channels (29). The importance of identifying a channelopathy as the cause of death is not only to help the family come to an understanding of why their child died but to alert the family to the possibility of a sibling having the same mutation and to refer him or her for evaluation. Other genetic abnormalities have been found in infants who die suddenly and unexpectedly, such as medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (MCAD) deficiency, which is the most common inherited disorder of fatty acid metabolism, which presents in early childhood with a potentially fatal episode of hypoketotic hypoglycemic crisis (28).

An apparent life-threatening event (ALTE), which used to be termed “near miss SIDS,” is defined as “an episode that is frightening to the observer, since it is characterized by some combination of apnea (centrally or occasionally obstructive), color change (usually cyanotic or pallid, but occasionally erythematosus or plethoric), and marked change in muscle tone (usually marked limpness), choking or gagging” (31). In approximately half of these cases, an underlying etiology such as episodic gastroesophageal reflux, respiratory infection, and seizure disorder is found. The other half are termed idiopathic (32). Current research has focused on polymorphisms in genes that regulate brainstem neurotransmitters. The medullary serotonin or 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) system with the serotonin transporter gene (5-HTT) regulates multiple autonomic homeostatic functions such as ventilation, thermoregulation, and arousal (28). Abnormalities in the genes that regulate these functions can have serious consequences and thus are thought to possibly play a role in sudden infant deaths. Serotonin seems to play a role in these deaths and may be a valuable tracer for the risk of SIDS in a child with idiopathic ALTE (32). There have been varying reports as to the number of infants who have experienced an ALTE prior to a lethal episode.

Sudden Unexplained Infant Death (SUID)

SUID utilizes the findings in SIDS but adds in one or a number of the above-mentioned risk factors. The most common investigative findings that result in a death being deemed an SUID instead of an SIDS is bed sharing with an adult in an adult-sized bed (Figure 7-5). Bed sharing is a controversial subject with many believing it is an unsafe sleep environment and others believing it to be safe and promote bonding between the caregiver and child. A nationwide telephone survey revealed that 19.4% of mothers shared a bed with their infant more than 50% of the time, 27.6% bed shared sometimes, and 52.7% never bed shared (33). Another study in Oregon, which represented a greater diversity in its study population, revealed that 35.2% of mothers frequently bed shared, 41.4% sometimes bed shared, and 23.4% never did (34). This, or any of the other risk factors of an unsafe sleep environment, raises the possibility of an asphyxial death, but there is no way to prove it without a confession from the caregiver that the caregiver, or another individual in the bed, was lying on top of the child when he/she was found (see following section for asphyxial deaths) or that the face was

covered in some manner. The weakness of the infant neck muscles makes the infant more prone to asphyxia as a result of rebreathing carbon dioxide and decreased oxygen intake. The autopsies in these cases are most often also essentially negative, but the history or scene investigation shows an unsafe environment.

covered in some manner. The weakness of the infant neck muscles makes the infant more prone to asphyxia as a result of rebreathing carbon dioxide and decreased oxygen intake. The autopsies in these cases are most often also essentially negative, but the history or scene investigation shows an unsafe environment.

Asphyxia

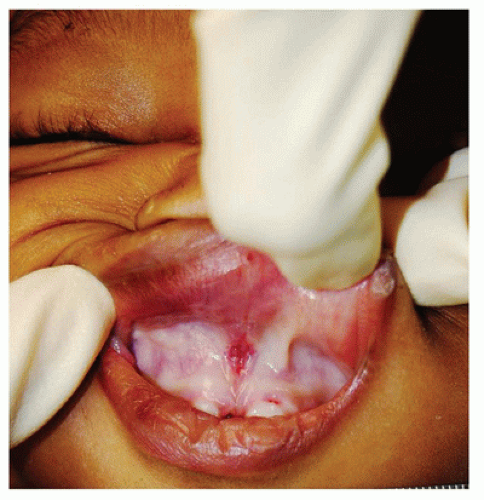

The autopsy of a child who died of asphyxia is also quite often completely negative. For this reason, the investigation may hold the key to determining the cause of death to be asphyxia. This may be elucidated by a doll re-enactment with photographs, documentation of the postmortem changes at the scene, and witness accounts. The autopsy in these cases may show pallor over the nose and mouth, indicating pressure over these areas, or a line of demarcation in lividity suggestive of compression (Figure 7-6). Asphyxial deaths can result from wedging (the child wedged between two surfaces such as a mattress and wall), overlaying (an individual found lying on top of the child), or obstruction of the face (such as by a blanket or pillow). Overlaying is most often seen in children less than 5 months of age but has been found in children up until 2 years of age (35). As the number of bed sharers increases so does the risk of overlaying. The bed sharers do not need to be adults. There have been documented cases of other children, often siblings, found lying on top of one another where the child located beneath the other child was dead. Parental intoxication increases the risk of overlaying, and some states have even considered criminal charges against these parents. The child may not be able to cry out as the mouth and nose may be covered and the thorax compressed. If the history conveyed by the caregiver suggests the possibility of overlaying but external examination reveals multiple cutaneous or oral injuries, inflicted trauma should be strongly considered. Homicidal asphyxia, such as smothering, can be very difficult to diagnose at autopsy as these examinations may be completely unremarkable as well. In these cases, the pathologist should pay specific attention to the oral region. One may see abrasions of the lips or nose and lacerations of the mucosal surface of the lips or frenula (Figure 7-7). There has been the suggestion by some that severe pulmonary hemorrhage and/or a marked number of intra-alveolar siderophages is consistent with an asphyxial death. Krous et al. looked at 444 cases of infant deaths that were determined to die of SIDS, accidental suffocation, or inflicted suffocation (36). They reviewed the files and microscopic slides to evaluate for intrathoracic petechiae, pulmonary hemorrhage, and siderophages. They

determined that any of these findings in isolation cannot confidently be used to distinguish between a diagnosis of SIDS or suffocation, but if there is significant pulmonary hemorrhage, a thorough inspection of the body for signs of trauma should be considered. In addition, when the number of intra-alveolar siderophages is prominent, the diagnosis of idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis should be considered (37). This is a rare disease with a possible hereditary component and a clinical history of cough and hemoptysis. In the acute setting, acute pulmonary hemorrhage is its usual presentation.

determined that any of these findings in isolation cannot confidently be used to distinguish between a diagnosis of SIDS or suffocation, but if there is significant pulmonary hemorrhage, a thorough inspection of the body for signs of trauma should be considered. In addition, when the number of intra-alveolar siderophages is prominent, the diagnosis of idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis should be considered (37). This is a rare disease with a possible hereditary component and a clinical history of cough and hemoptysis. In the acute setting, acute pulmonary hemorrhage is its usual presentation.

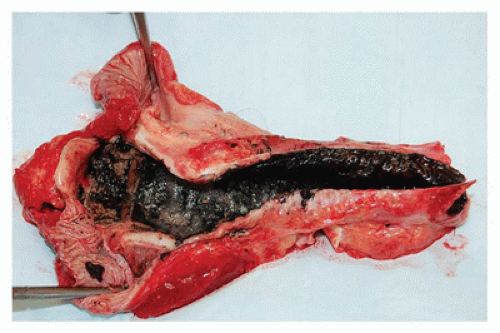

Special subtypes of asphyxia include drowning and smoke inhalation. In drowning deaths, a full autopsy examination should be performed in an attempt to identify any natural disease or traumatic event that may have led to the drowning. In infants, drowning often occurs in the bathtub, especially if they are not attended to appropriately, whereas toddlers drown in pools more often as they may wander and enter the pool without the ability to swim. Once adolescence is reached, the risks change to include open bodies of water. Toxicologic analysis should be performed in these cases as often there is the combination of alcohol and swimming that contribute to the death of these adolescents. Young children are considered a high-risk group for deaths due to smoke inhalation, the most common scenario occurring as a result of a house fire. Autopsy examination of these children should be performed not only to test for a carboxyhemoglobin level but also to rule out other injuries. Carboxyhemoglobin saturation is one test used to identify if the child may have been alive prior to the start of the fire, which will be displayed by a carboxyhemoglobin level of 10% or more. Indicators that suggest carbon monoxide exposure include cherry-red lividity and cherry-red discoloration of the viscera. Black soot may be found focally or throughout the tracheobronchial tree (Figure 7-8).

FIGURE 7-9 • Suicidal hanging. A: Note that the body is not fully suspended. Only the weight of the head is necessary to cause death. B: Ligature furrow on the neck after removal of the ligature. |

Accidental strangulation is another form of asphyxia that used to be seen more often but has decreased in incidence due to the acts of the Consumer Product Safety Commission, public awareness, and manufacturing changes. Common household items that have led to accidental strangulation include pull strings on window blinds and pacifier strings. Ligature hanging can be seen in the teenage years as a result of suicidal intent or accidentally due to autoerotic asphyxia or “pass out games.” Just the weight of the head is needed to cause death via hanging; thus, it is not uncommon to find the individual sitting, kneeling, or with the feet touching the ground (Figure 7-9A). These cases deserve the attention of the medical examiner due to the sensitive nature of these deaths. Determining the cause and manner of death in these cases may elicit strong emotional responses from families. External examination of the neck in any form of hanging may reveal a ligature furrow around the neck. This is usually composed of an area of depression with abrasion or dried yellow skin. The furrow usually has a horizontal orientation on the anterior neck and angles upward and backward behind both ears in suicidal hangings but may have a different configuration

in other types of hangings, depending on the position of the body (Figure 7-9B). The furrow findings will be present if the individual was hanging for at least a number of minutes to hours. Internal examination of the neck should reveal the lack of intramuscular hemorrhage in the strap muscles, and there should not be any fracture of the hyoid bone or thyroid cartilage. The same is true in the case of autoerotic asphyxia, except that the ligature furrow may have varying configurations depending on the apparatus that was used. Autoerotic asphyxia describes an act performed by an individual seeking to heighten orgasm by restricting oxygen to the brain. This is usually done by placing a ligature around the neck, which is attached to an escape mechanism that allows the person to release the tension on the neck prior to passing out. Essentially, these deaths are due to the failure to utilize the escape mechanism in a timely manner, most likely due to the individual losing consciousness. Once again, scene investigation may be the most important aspect of the investigation. Suicidal hangings may have a “note of intent” at the scene, or messages may be found on the individual’s phone or social media account that sheds light on his or her mental state. In autoerotic asphyxia cases, the scene has often been altered prior to law enforcement or emergency medical services arrival due to the social stigma that may accompany this type of death. At the scene of an autoerotic asphyxial death, look for any sort of pornography, clothing of the opposite sex, and any information on the deceased’s computer that may indicate the possibility of experimentation. The manner of death in autoerotic asphyxia cases is accident. The mechanism of death in any of these cases is usually one of vascular occlusion and not as a result of airway occlusion. Depending on the width of the ligature used, pressure will be placed on the jugular veins first and carotid arteries next. Petechiae can be seen on the conjunctivae, oral mucosa, and face when the drainage of blood from the brain is halted due to occlusion of the veins with continuation of blood supply to the brain through the carotid arteries. Asphyxial games (a.k.a. the choking game, Space Monkey, Funky Chicken, etc.) are becoming more prevalent in the teenage population. Autopsy findings include florid facial petechiae, but often, there is absence of conjunctival petechiae. These games are often performed in isolation, as opposed to historically being done in groups. The mechanism of death is similar to those of autoerotic asphyxia, but there is no elaborate setup and no sexual connection. If the right questions are asked, the investigator may be able to elicit a history of playing this game with a continuous attempt to prolong the length of time of asphyxia (38). Cervical spine fracture, “hangman’s fracture,” is not seen in any of the above described cases as they occur in judicial hangings or the rare instance where an individual jumps from a height with a noose around the neck. There needs to be a drop from a height with rapid deceleration to cause this type of fracture.

in other types of hangings, depending on the position of the body (Figure 7-9B). The furrow findings will be present if the individual was hanging for at least a number of minutes to hours. Internal examination of the neck should reveal the lack of intramuscular hemorrhage in the strap muscles, and there should not be any fracture of the hyoid bone or thyroid cartilage. The same is true in the case of autoerotic asphyxia, except that the ligature furrow may have varying configurations depending on the apparatus that was used. Autoerotic asphyxia describes an act performed by an individual seeking to heighten orgasm by restricting oxygen to the brain. This is usually done by placing a ligature around the neck, which is attached to an escape mechanism that allows the person to release the tension on the neck prior to passing out. Essentially, these deaths are due to the failure to utilize the escape mechanism in a timely manner, most likely due to the individual losing consciousness. Once again, scene investigation may be the most important aspect of the investigation. Suicidal hangings may have a “note of intent” at the scene, or messages may be found on the individual’s phone or social media account that sheds light on his or her mental state. In autoerotic asphyxia cases, the scene has often been altered prior to law enforcement or emergency medical services arrival due to the social stigma that may accompany this type of death. At the scene of an autoerotic asphyxial death, look for any sort of pornography, clothing of the opposite sex, and any information on the deceased’s computer that may indicate the possibility of experimentation. The manner of death in autoerotic asphyxia cases is accident. The mechanism of death in any of these cases is usually one of vascular occlusion and not as a result of airway occlusion. Depending on the width of the ligature used, pressure will be placed on the jugular veins first and carotid arteries next. Petechiae can be seen on the conjunctivae, oral mucosa, and face when the drainage of blood from the brain is halted due to occlusion of the veins with continuation of blood supply to the brain through the carotid arteries. Asphyxial games (a.k.a. the choking game, Space Monkey, Funky Chicken, etc.) are becoming more prevalent in the teenage population. Autopsy findings include florid facial petechiae, but often, there is absence of conjunctival petechiae. These games are often performed in isolation, as opposed to historically being done in groups. The mechanism of death is similar to those of autoerotic asphyxia, but there is no elaborate setup and no sexual connection. If the right questions are asked, the investigator may be able to elicit a history of playing this game with a continuous attempt to prolong the length of time of asphyxia (38). Cervical spine fracture, “hangman’s fracture,” is not seen in any of the above described cases as they occur in judicial hangings or the rare instance where an individual jumps from a height with a noose around the neck. There needs to be a drop from a height with rapid deceleration to cause this type of fracture.

Injuries, Nonaccidental and Accidental

Injuries to a child may be accidental or nonaccidental. Children who present with injuries should be examined by a physician who specializes in the evaluation of these types of injuries. This is of vital importance in order to avoid a false accusation of child abuse and possible criminal conviction of an individual who is innocent and vice versa. It is important to note that the lack of external trauma does not rule out inflicted injury as significant internal injuries can be found without any external evidence. Conversely, external trauma does not necessarily correlate with internal injuries and is not definitively diagnostic of child abuse. When documenting injuries, the distribution, pattern, and severity of the injuries need to be considered. Does the overall injury profile correlate with the history given? Epidemiologic studies have shown that the most common perpetrator of child abuse is the biologic father followed by the mother’s boyfriend. Often, there is the given history of a minor fall at home, which does not correlate with the injuries found to the child, or that the child was found unresponsive with no traumatic history. The true incidence of inflicted head injury is not known as the child may present with nonspecific signs that resolve, and a false diagnosis, such as a viral syndrome, may be given. The most common form of abusive injury is that of head trauma with abdominal trauma being the second most common form of inflicted trauma. Hospitalization rates for abused children aged 0 to 3 years have remained relatively stable at 2.36 per 10,000 over the last 14 years, the most prevalent group being those under 1 year old. If there is a previous report from child protective services concerning a specific child, there is a 3 times higher risk of that child suffering a sudden unexplained death (39).

Blunt Force Injuries

The most common form of injury found in child death investigation is that of blunt force. The cutaneous manifestations are usually in the form of contusions, abrasions, or lacerations. A contusion (bruise) is the result of a blunt impact that tears the subcutaneous vessels leading to bleeding beneath the skin (Figure 7-10). Of note, a contusion should not be aged on gross examination; thus, punch biopsies of identified contusions should be processed for microscopic examination. Many variables may affect the color and size of a contusion, including the individual’s skin color, coagulation disorders,

inflammatory disorders, hormonal abnormalities, depth of the bleeding, location on the body, amount of blood, and the light in which the injury is evaluated. Studies of bruising in adults showed development of a bruise within 30 minutes of a traumatic insult. The size of the contusion varied but generally decreased over time (40). The one color change that may be utilized is that yellow discoloration indicates at least 18 hours since the onset of the injury due to the presence of hemosiderin. Histology may be helpful in the determination of aging a contusion but is still an estimation and not specific. In general, perivascular polymorphonuclear leukocytes may be visible around 4 hours after injury, with a peripheral infiltration by around 12 hours. Macrophages peak around 16 to 24 hours and may contain hemosiderin by 72 hours. Fibroblasts may appear at 2 to 4 days (41). An abrasion (scrape) is the result of shearing off of the superficial layers of the epidermis (Figure 7-11). A laceration is a splitting of the skin due to a blunt impact. Examining the depths of a laceration may reveal strands of vessels and nerves “bridging” one side of the wound to the other (Figure 7-12). This helps in distinguishing a laceration from a stab wound, which will cut across all of the deep tissues, including the vessels and nerves.

inflammatory disorders, hormonal abnormalities, depth of the bleeding, location on the body, amount of blood, and the light in which the injury is evaluated. Studies of bruising in adults showed development of a bruise within 30 minutes of a traumatic insult. The size of the contusion varied but generally decreased over time (40). The one color change that may be utilized is that yellow discoloration indicates at least 18 hours since the onset of the injury due to the presence of hemosiderin. Histology may be helpful in the determination of aging a contusion but is still an estimation and not specific. In general, perivascular polymorphonuclear leukocytes may be visible around 4 hours after injury, with a peripheral infiltration by around 12 hours. Macrophages peak around 16 to 24 hours and may contain hemosiderin by 72 hours. Fibroblasts may appear at 2 to 4 days (41). An abrasion (scrape) is the result of shearing off of the superficial layers of the epidermis (Figure 7-11). A laceration is a splitting of the skin due to a blunt impact. Examining the depths of a laceration may reveal strands of vessels and nerves “bridging” one side of the wound to the other (Figure 7-12). This helps in distinguishing a laceration from a stab wound, which will cut across all of the deep tissues, including the vessels and nerves.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree