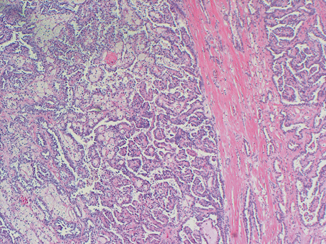

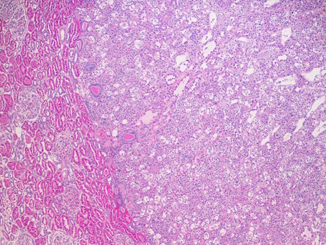

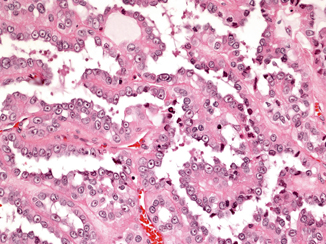

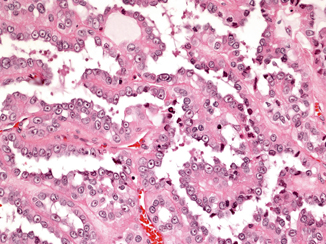

Fig. 29.1

Clear cell RCC, ISUP grade 2. H & E × 100

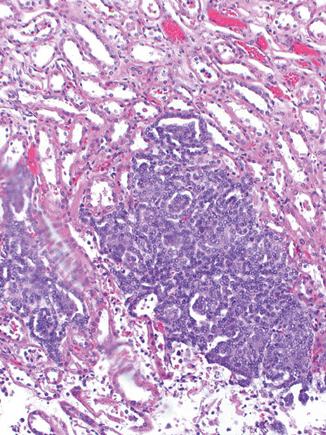

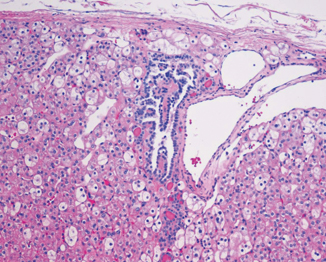

Cysts are a common element of VHL. They vary in size, and may be lined by rows of clear cells that can have proliferative and papillary growths protruding to the lumen of the cyst. (Fig. 29.2). Not infrequently, the cysts may be associated with areas of prominent fibrosis in which nests of clear cells are trapped.

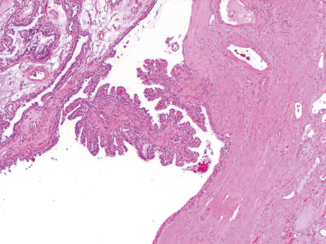

Fig. 29.2

Simple renal cyst with focal papillary formation. H & E × 100

The adjacent renal parenchyma may show small clusters of clear cells that probably represent the beginning of new lesions. Molecular studies have shown that these smaller lesions already share similar molecular alterations to the larger tumors.

Treatment of most cases of VHL is surgical, aimed to remove as many tumors as possible before they reach a large size. Metastases in these patients generally occur when tumors are larger than 3 cm. Patients may have long survivals (10–20 years) but metastasis can develop in lung, bone, retroperitoneum, pancreas, and brain. Patients with VHL-associated renal tumors have a better prognosis and longer survivals than those with sporadic RCC. Long-term follow-up of patients with VHL as well as screening of family members is necessary, even if they are children.

Hereditary Papillary RCC

Hereditary papillary renal cell carcinoma (HPRCC) is an autosomal dominant disease with reduced penetrance, characterized by the development of multifocal papillary type I renal cell tumors. Since the original description of the entity by Zbar in 1994 [3], HPRCC has been recognized and established as a new hereditary syndrome.

The disease is caused by mutations in the tyrosine-kinase domain of the c-MET proto-oncogene on 7q34 [4]. Activation of the c-Met/hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) signaling pathways is known to be involved in many functions such as cell motility, differentiation, cell proliferation, and invasion [5]. Trisomy of chromosome 7 is thought to be the initiating event along with the loss of a sex chromosome. It is estimated that approximately half the members of affected families will develop tumors by the age of 50 years. Clinically and radiographically, the manifestations are similar to those of VHL, that is, patients present with bilateral and multifocal tumors.

Pathology

Grossly the renal tumors are multifocal and of variable sizes. Unlike VHL, simple cysts are not identified in this syndrome, although some of the tumors may have a cystic appearance. The adjacent renal parenchyma may show smaller lesions, adenomas, and incipient microscopic lesions that probably represent new tumors.

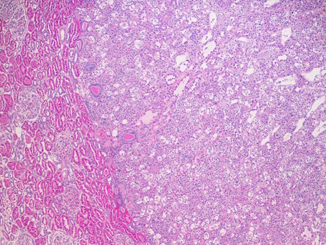

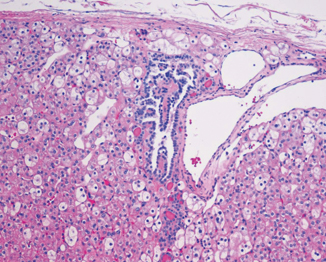

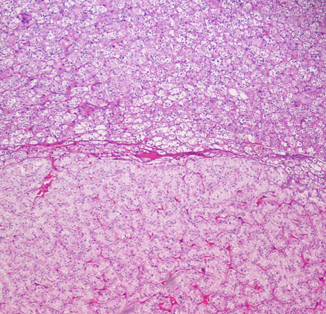

Morphologically, HPRCC tumors show a papillary, tubulopapillary or solid architecture. A fibrous pseudocapsule may surround the tumor nodules (Fig. 29.3). The papillae are short and thin with fibrovascular cores lined by neoplastic cells. These cells have regular small nucleoli with scant amounts of amphophilic cytoplasm. The centers of the papillae are frequently filled by collections of macrophages. In the solid areas, complex papillae may form structures resembling glomeruloid bodies. Marked nuclear atypia and mitotic figures are usually rare. However, cases with large tumors associated with areas of hemorrhage and necrosis have been reported. These tumors follow a more aggressive course and have a tendency to metastasize to lymph nodes and lung. Early or incipient lesions can be found scattered throughout the adjacent renal parenchyma and may have a papillary, solid, or tubular appearance (Fig. 29.4) [6].

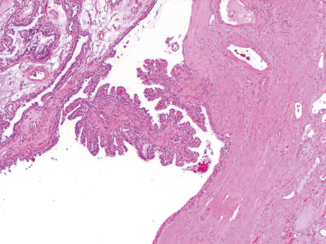

Fig. 29.3

Papillary RCC type I. Notice the pseudocapsule around the tumor and the papillary configuration. × 100 H & E I. H & E × 100

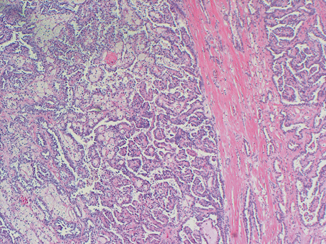

Fig. 29.4

Incipient lesion showing “glomeruloid” structures. × 200 H & E

Areas of clear cell differentiation have been described in HPRCC tumors but they occur predominantly as changes in the cells bordering the papillae which become larger and similar to the cells seen in clear cell tumors.

HPRCC tumors stain strongly positive for CK7, and are negative for CK20 and Wilm’s tumor protein 1 (WT1). Treatment of patients with HPRCC is similar to VHL consisting of tumor excisions and long-term follow-up. These tumors have metastatic potential, primarily to lymph nodes and lungs. When they occur, the metastases are morphologically similar to the primary tumors. Targeted therapies have shown promising results in the treatment of patients with metastatic disease.

Birt–Hogg–Dubé Syndrome

In 1977, Drs. Birt, Hogg, and Dubé described a familial syndrome characterized by a predisposition to develop multiple small papules on the face and neck [7]. These papules are benign tumors of the hair follicles (fibrofolliculomas). The syndrome has since been redefined, and it is now known that BHD is an autosomal dominant genodermatosis that predisposes to the development of skin fibrofolliculomas as well as spontaneous pneumothorax, lung cysts and renal neoplasms [8]. It is believed that approximately 15–35 % of affected BHD individuals will develop renal tumors, that are morphologically distinct from those occurring in other hereditary syndromes [9] .

Clinically, the disease presents with bilateral and multifocal tumors, with a median age of diagnosis of 48 years and a male to female ratio of 2.5:1. Approximately 30 % of the patients present with history of spontaneous pneumothorax and most of these cases have associated lung cysts that are more often found in the lower lobes of the lungs.

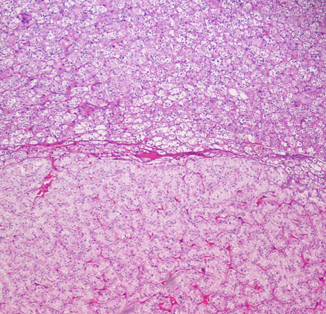

BHD patients are at risk to develop chromophobe RCC, oncocytomas, and hybrid tumors. Hybrid tumors and chromophobe RCC are the predominant types. Clear cell RCC can occur as well, but it is uncommon. The size of tumors at presentation is variable. The hybrid tumors average 2.2 cm, the chromophobe RCCs 3.0 cm, and the clear cell RCCs 4.7 cm in diameter. Morphologically, hybrid tumors are characterized by the presence of oncocytoma-like cells and chromophobe cells with granular eosinophilic cytoplasm and small regular pyknotic nuclei surrounded by characteristic perinuclear halos and well-defined cell borders. Cells with clear/pale cytoplasm and crisp borders may be present. Typically, hybrid tumors exhibit nests with an admixture of all these types of cells. These tumors are not encapsulated, blend regularly with the adjacent parenchyma, and may have a central myxohyaline scar (Figs. 29.5 and 29.6) [10]. The percentage of different cell types in the hybrid tumors has no clinical impact.

Fig. 29.5

Hybrid tumor. Notice the demarcation from the adjacent renal parenchyma. H & E × 100

Fig. 29.6

Oncocytic cells mixed with clear and chromophobe type cells. H & E × 150

Nodules of classic chromophobe RCC can be found growing within some hybrid tumors and may compress the hybrid component to the periphery. These nodules exhibit only one type of chromophobe cells and their homogeneity differentiates them from the hybrid tumor, where the admixture of different types of chromophobe cells confers a more heterogeneous appearance (Fig. 29.7).

Fig. 29.7

Chromophobe RCC (CMF) arising in association with a hybrid tumor (HYB). H & E × 100

IHC demonstrates that Mib-1 proliferation index is low in hybrid tumors, with few nuclei staining for p53. CD117 shows a patchy pattern in the hybrid component in contrast to the diffuse pattern of chromophobe RCC. Nontumoral renal parenchyma shows oncocytosis in about 56 % of the cases, consisting of poorly circumscribed lesions as small as a few cells in diameter that tend to expand into adjacent renal tubules. Cells within the areas of oncocytosis have eosinophilic cytoplasm, well-defined borders, large nuclei with stippled heterochromatin, and occasional focal cytoplasmic clearing. Recombination mapping in BHD families has identified the gene on chromosome 17p11.2; the gene product is known as folliculin. The treatment of patients with BHD is similar to that of patients with VHL and HPRCC.

When possible, nephron-sparing surgery is the treatment of choice, depending on the size and location of the tumors. Total nephrectomy may be necessary in some cases [11].

Molecular genetic testing for the family-specific mutation allows for early identification of at-risk family members, improves diagnostic certainty and reduces costly screening procedures in relatives who have not inherited the family-specific disease-causing mutation.

The prognosis of patients with these tumors is better than that of HPRCC and VHL patients, unless clear cell RCC develops .

Hereditary Leiomyomatosis Renal Cell Carcinoma

Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell carcinoma (HLRCC) is an autosomal dominant familial syndrome with incomplete penetrance, characterized by the development of cutaneous and uterine leiomyomas as well as renal tumors. In 2001, Launonen et al. [12] reported on the clinical, histopathologic and, molecular features of a cancer syndrome with predisposition to uterine leiomyomas and papillary renal cancer. Genetic evaluation of families with this disorder found germ line mutations in the gene encoding an enzyme of the Krebs cycle and fumarate hydratase ( FH, 1q42.3-q43). Mutations of the FH gene were also found in the germ line of some multiple cutaneous leiomyomatosis (MCL) kindreds [13]. It is now believed that MCL and HLRCC are the same disorder. The four original kidney cancer cases reported occurred in young females, had papillary architecture, and presented as unilateral solitary lesions that had metastasized at the time of diagnosis.

HLRCC is the only hereditary syndrome that presents with single unilateral masses that may be cystic in some patients. Three distinct patterns of imaging features have been seen in patients with HLRCC renal tumors. These patterns are characterized as homogeneous and poorly enhancing solid lesions, predominantly cystic with small solid component lesions and heterogenous solid lesions with necrosis. Cystic lesions with smaller, distinctly solid enhancing components and ranging in size from 2.5 to 10 cm are commonly identified [14].

Although the original report described all the tumors as papillary type II, better understanding of the disease has demonstrated a variety of morphologic patterns including tubular, solid, and papillary and mixed. In the papillary tumors, the papillae are thick, with stalks containing vascular structures and abundant collagen [15].

The cells lining the papillae are large, contain abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and occasionally have nuclei arranged in a pseudostratified manner resembling the rosettes seen in ependymomas (Fig. 29.8). The hallmark of these neoplasms is the presence of large nuclei with prominent orangeophilic nucleoli (Fig. 29.9). These nuclear traits are seen in the majority of the cells, whether lining the papillary or tubular structures. Other nuclear features include marked pleomorphism and irregularities of the nuclear membrane. Frequently, the tumors show cystic dilatation in which papillary structures can be identified [16]. Association with areas of clear cell differentiation can occur, but the nuclear changes are present in the clear cells as well. All cases of HLRCC should be considered high grade.

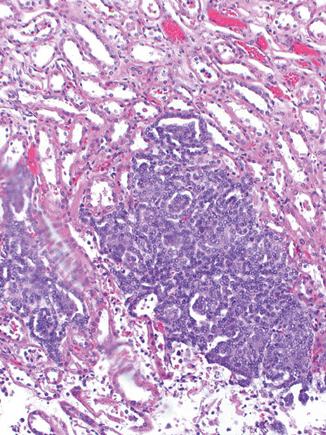

Fig. 29.8

HLRCC with papillary configuration. H & E × 150

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree