39

CHAPTER OUTLINE

Pathologic gambling is a psychiatric disorder character-ized by persistent and recurrent maladaptive patterns of gambling behavior, which is associated with impaired functioning, reduced quality of life, and high rates of bankruptcy, divorce, and incarceration (1). Excessive gambling behaviors have been reported for millennia across cultures and have been discussed in the medical literature since the early 1800s (2). Pathologic gambling, however, was recognized by the American Psychiatric Association only in 1980 in their third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-III) (3).

Currently classified in DSM-5 as an “non-substance-related disorder,” the diagnosis of gambling disorder requires that a person meet five of the possible 9 criteria listed for the disorder. These criteria include (a) gambles when distressed; (b) the need to gamble with higher amounts of money (tolerance); (c) has tried unsuccessfully to stop or cut back on gambling; (d) feels restless or irritable when not able to gamble; (e) gambles to escape from a mood or problems; (f) chasing losses; (g) lies to family, friends, and others about the amount or extent of gambling; (h) has lost or put into jeopardy a job, educational, or other opportunity due to gambling; and (i) has needed others to pay for finances due to gambling losses. Further, the gambling must not be better accounted for by a manic episode. The term problem gambling has been used to describe forms of disordered gambling, sometimes inclusive and at other times exclusive of pathologic gambling. Problem gambling, like problem drinking, is not an officially recognized disorder by the American Psychiatric Association.

The concept of behavioral addictions has some scientific and clinical heuristic value but remains controversial (see Chapter 5). This is probably so because pathologic gambling is often resistant to treatment, and it remains unclear whether the treatment technologies of traditional addiction treatment (group, 12-step participation, relapse prevention, motivational enhancement, etc.) are superior, inferior, or equivalent or need to be combined with those of psychiatric treatments (medication, cognitive–behavioral therapy [CBT], psychotherapy). Nonetheless, evidence supports significant phenomenologic, clinical, epidemiologic, and biologic links with substance use disorders (4,5). These data support the conceptualization of pathologic gambling as a “behavioral”—as opposed to a chemical—addiction. Issues around behavioral addictions were debated in the context of development of DSM-5 (6). Not only is substance use disorder research likely to be illustrative for pathologic gambling, but the study of pathologic gambling presents an opportunity to study addictive behaviors without necessarily being confounded by neurotoxicity associated with acute or chronic substance use (7). As such, it seems increasingly important that individuals involved in the prevention and treatment of substance use disorders have a current understanding of pathologic gambling and the potential for future research findings to guide prevention and treatment efforts for addictions in general.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

A range of prevalence estimates have been reported for pathologic gambling depending upon the time frame of the study and the instruments used to diagnose the disorder. Only four national studies and one meta-analysis of state and regional surveys have examined prevalence estimates of pathologic gambling in the general US population. The first national study in 1976 noted that 0.8% of 1,749 adults contacted via telephone survey had a significant gambling problem (8). Twenty years later, the National Opinion Research Center at the University of Chicago conducted a national telephone survey (requested by the National Gambling Impact Study Commission) of 2,417 adults and found a lifetime prevalence estimate of 0.8% of pathologic gambling and an additional 1.3% of problem gambling (9). Another national telephone survey of 2,628 adults found that 1.3% had current pathologic gambling measured by the Diagnostic Interview Schedule and 1.9% when measured by the South Oaks Gambling Screen, and an additional 2.8% to 7.5% had problem gambling (10). A recent study, the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC), however, found that only 0.42% of adults in a community sample met current criteria for pathologic gambling (11). A meta-analysis of 120 prevalence estimate surveys completed in North America from the late 1970s to the late 1990s found that the lifetime estimate of pathologic gambling was 1.6% and of problem gambling was 3.85%, and for a combined rate of 5.45% for some kind of disordered gambling (12); however, gambling exposure may influence prevalence rates of pathologic gambling (13). A global public health concern, similar rates of pathologic gambling have been reported in other countries (14–18).

The incidence of pathologic gambling appears higher in clinical samples. In subjects seeking treatment for substance use disorders, lifetime estimates of pathologic gambling range from 5% to 33% (19–21). In studies of psychiatric inpatients, estimates of lifetime pathologic gambling have ranged from 4.9% in adolescents to 6.9% in adults (22–25).

There has been an accelerated proliferation of gambling venues during the past decade, particularly with online gaming, Native American casinos, and riverboat gambling (26,27). With increased opportunity to gamble, some research suggests that we can expect greater rates of patho-logic gambling in the future (12,28,29). Physicians, therefore, will likely be seeing more individuals struggling with pathologic gambling and need to be skilled in assessing and treating this disorder.

Clinical Characteristics

Pathologic gambling often begins in adolescence or early adulthood, with males tending to start at earlier ages (12,30,31). Although prospective studies are largely lacking, pathologic gambling appears to follow a trajectory similar to that of substance dependence, with high rates in adolescent and young adult groups, lower rates in older adults, and periods of abstinence and relapse (32). Pathologic gambling can be a serious psychiatric disorder, but there is recent evidence that approximately one-third of individuals with pathologic gambling experience natural recovery (i.e., without formal treatment or attendance at Gamblers Anonymous) (33). The research on natural recovery, however, is based on retrospective reports, and there are no data regarding whether these individuals who are symptom free for 1 year remain free of symptoms beyond that time or whether they relapse or change addictions.

Significant clinical differences have been observed in men and women with pathologic gambling (34,35). Men with pathologic gambling are more likely to be single and living alone as compared to women with the disorder (36). Male pathologic gamblers are also more likely to have sought treatment for substance abuse (37), have higher rates of antisocial personality traits (30), and have marital consequences related to their gambling (30). Though men seem to start gambling at earlier ages and have higher rates of pathologic gambling, women, who constitute approximately 32% of pathologic gamblers in the United States, seem to progress more quickly to severe consequences than do men (38–40). But, women with pathologic gambling are more likely to recover from and to seek treatment for their gambling problem (41).

The types of gambling preferred by men tend to be different from those preferred by women. Men with pathologic gambling have higher rates of “strategic” forms of gambling, including sports betting, video poker, and blackjack. Women, on the other hand, have higher rates of “nonstrategic” gambling, such as slot machines or bingo (39,42). In regard to gambling triggers, though both men and women report that advertisements trigger their urges to gamble, men tend to report gambling for reasons unrelated to their emotional state, whereas women report gambling to escape from stress or owing to depressive states (31,37,39,42,43). Higher rates of sensation-seeking or “action”-seeking behavior in men have been suggested as a possible reason for this difference in gambling preference (39,44,45).

Functional Impairment, Quality of Life, and Legal Difficulties

Individuals with pathologic gambling suffer significant impairment in their ability to function socially and occupationally. Many individuals report intrusive thoughts and urges related to gambling that interfere with their ability to concentrate at home and work (43). Work-related problems such as absenteeism, poor performance, and job loss are common (38). The inability to control behavior about which a person has mixed feelings may lead to feelings of shame and guilt (43). Pathologic gambling is also frequently associated with marital problems (43) and diminished intimacy and trust within the family (46). Financial difficulties (44% of pathologic gamblers report loss of savings or retirement funds, and 22% report losing homes or automobiles or pawning valuables owing to gambling) often exacerbate personal and family problems (43).

With the functional impairment that these individuals experience, it is not surprising that they also report poor quality of life. In three studies systematically evaluating quality of life, individuals with pathologic gambling reported significantly poorer life satisfaction compared to general, nonclinical adult samples (47–49).

Pathologic gambling is also associated with greater health problems (e.g., cardiac problems, liver disease) and increased use of medical services (50–54). Possible reasons for the association of pathologic gambling with health problems might be the sedentary nature of gambling, reduced leisure and exercise time, reduced sleep (55), increased stress, and increased nicotine and alcohol consumption (11).

Many individuals with pathologic gambling report the need for psychiatric hospitalization owing to the depression, and rarer, suicidality, they feel was brought on by their gambling losses (42). Research on individuals in gambling treatment centers has found that 48% of individuals report having had gambling-related suicidal ideation at some time (56). The often overwhelming financial consequences, such as bankruptcy (57), associated with pathologic gambling may also contribute to attempted or completed suicide. A study of Gamblers Anonymous participants (recruited through a gambling telephone hotline) found that 17% to 24% reported having attempted suicide owing to gambling (58).

In addition to the emotional impact of problem and pathologic gambling, many individuals with pathologic gambling have faced legal difficulties related to their gambling. One study found that 27.3% of pathologic gamblers had committed at least one gambling-related illegal act (59). Problem or pathologic gambling may lead people to engage in illegal behavior including embezzlement, stealing, and writing bad checks in order either to finance the gambling behavior or to compensate for past losses related to the excessive gambling (58). Another study found high percentages of pathologic gamblers endorsing prior acts of embezzlement (31%) and robbery (14%) (60).

Although pathologic gambling is associated with multiple legal and functional difficulties, one caveat is that the research is based on relatively small numbers of individuals seeking treatment for pathologic gambling, and therefore, these studies may reflect the more severe cases of pathologic gambling.

Comorbidity

Psychiatric comorbidity is common in individuals with pathologic gambling (61). Frequent co-occurrence has been reported between substance use disorders (including nicotine dependence) and pathologic gambling, with the highest odds ratios generally observed between gambling and alcohol use disorders (10,62,63). A Canadian epidemiologic survey estimated that the relative risk for an alcohol use disorder is increased 3.8-fold when disordered gambling is present (64).

Among clinical samples, 52% of Gamblers Anonymous participants reported either alcohol or drug abuse (65), and 35% to 63% of individuals seeking treatment for pathologic gambling also screened positive for a lifetime substance use disorder (1), rates notably higher than that found in the general population (26.6%) (66). Similarly, a recent study of 84 treatment-seeking pathologic gamblers noted lifetime rates of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in 26.3% of the sample, much higher than general population rates of 4% to 5% (67).

Other studies clinically assessing co-occurring disorders in treatment-seeking pathologic gamblers have also noted high estimates of mood disorders (34% to 78%) (43,68–70). In 1984, McCormick et al. (68) studied 38 cases of treatment-seeking pathologic gamblers with major depressive disorder and found that, in 86% of cases, the gambling problem preceded the onset of depression. These findings, however, need to be interpreted with caution because the majority of these studies were derived from treatment-seeking pathologic gamblers, which may or may not reflect non–treatment-seeking pathologic gamblers. Yet, they also raise the question of whether co-occurring mood disorders may be secondary to pathologic gambling. A twin study of self-reported family history to estimate shared genetic contributes to pathologic gambling and major depression in men (71), however, suggests a possible shared biologic predisposition to the co-occurrence of the disorders.

High prevalence estimates of co-occurring anxiety disorders (28% to 40%) also exist in pathologic gamblers (65,69), but not all anxiety disorders are seen with equal frequency (72). Research suggests that estimates of co-occurring generalized anxiety disorder range as high as 40% among pathologic gamblers (62), whereas those of obsessive–compulsive disorder may be as low as 1% (1). The relationship of obsessive–compulsive disorder to pathologic gambling, however, has produced a mixed picture, with some studies reporting high estimates (17% to 20%) (64,65) and other investigations generating low estimates (1%) (62). The rates of co-occurring disorders often have wide ranges, and this may be owing to lack of structured clinical interviews used in assessing comorbidity, the small sample sizes of gamblers assessed, sample selection, and the possible heterogeneity of pathologic gambling.

Significantly fewer data are available regarding the frequencies of Axis II personality disorders in pathologic gamblers. Studies have shown that estimates of any personality disorder in pathologic gamblers range from 25% to 93% (69,73–75). Borderline (3% to 70%), narcissistic (5% to 57%), avoidant (5% to 50%), and obsessive–compulsive (5% to 59%) personality disorders are most commonly reported (69,73–75). One of the best studied personality disorders in pathologic gambling, antisocial personality disorder, has been found in 15% to 40% of pathologic gamblers, a frequency higher than the 0.6% to 3% estimates reported for the general population (76,77). Although multiple reasons may explain the elevated rates of a comorbid antisocial personality disorder in pathologic gambling, evidence from past studies suggests a possible shared genetic vulnerability between pathologic gambling and antisocial personality disorder (78).

Family History

High frequencies of psychiatric disorders are seen in the first-degree relatives of those with pathologic gambling. Commonly reported conditions include mood, anxiety, substance use, and antisocial personality disorders (47,79,80). In two studies of first-degree relatives of pathologic gamblers, 17% to 33% had a mood disorder, and 18% to 24% reported an alcohol use disorder (65,79). In another study of 51 pathologic gamblers, 50% had a parent with an alcohol use disorder (80). A large sample of 517 pathologic gamblers revealed that subjects with at least one problem gambling parent were significantly more likely to have a father with an alcohol use disorder, report daily nicotine use, and have significantly worse legal and financial problems compared to the cohort without a problem gambling parent (81).

Studies have also found that 20% of the first-degree relatives of pathologic gamblers also have pathologic gambling (82). Recent research examining possible familial aggregation of pathologic gambling found that individuals with a problem gambling parent were at a 3.3 times higher risk of being a pathologic gambling (83). Similarly, Gambino et al. (84) found that problem gamblers at a Veterans Affairs hospital were up to eight times more likely to have a parent with a gambling problem than were nonproblem gamblers. In one of the few studies to use a psychometrically sound instrument (Family History Research Diagnostic Criteria) to collect family history data, the researchers found that 31% of first-degree relatives of pathologic gamblers had a lifetime alcohol use disorder and 19% had lifetime major depressive disorder (47).

In one of the few studies to use a control group to examine familial aggregation of psychiatric disorders among pathologic gamblers, Black et al. (85) examined 31 patho-logic gambler probands and 31 control probands. Lifetime estimates of pathologic gambling were significantly higher in family members of pathologic gamblers (8.3%) compared to control subjects (2.1%) (odds ratio of 4.49; p = 0.018). Similarly, elevated estimates were observed for substance use disorders (odds ratio of 4.21) and antisocial personality disorder (odds ratio of 7.73) (85).

TREATMENT

Psychotherapy

Although there is a long literature of case reports using psychodynamic psychotherapy and psychodynamic psychotherapy is often incorporated into multimodal, eclectic, and integrated approaches to pathologic gambling, there are no randomized controlled trials supporting its use (86). Similarly, although some evidence exists that Gamblers Anonymous (87–90) and self-exclusion contracts (91–94) may be beneficial for pathologic gamblers, limited and conflicting data assessing the long-term efficacy for these interventions have been published.

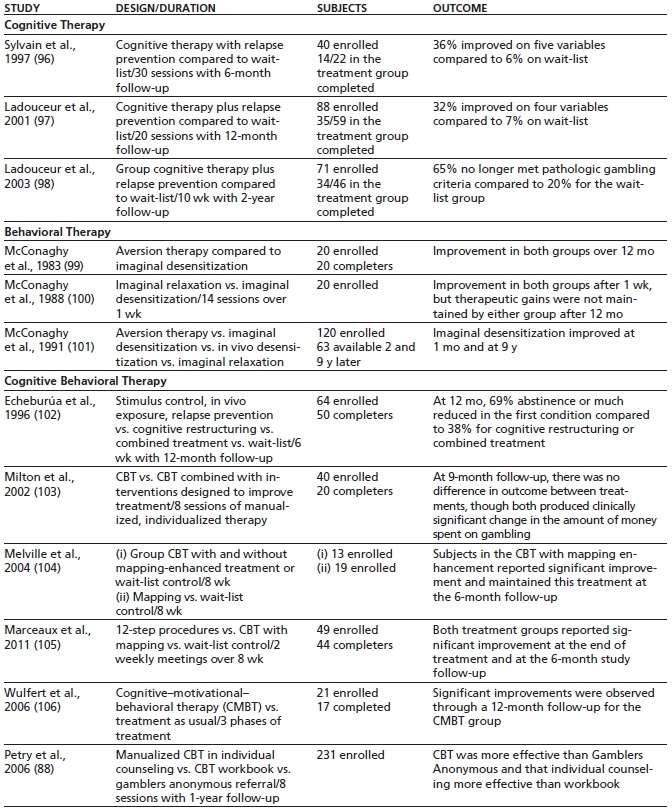

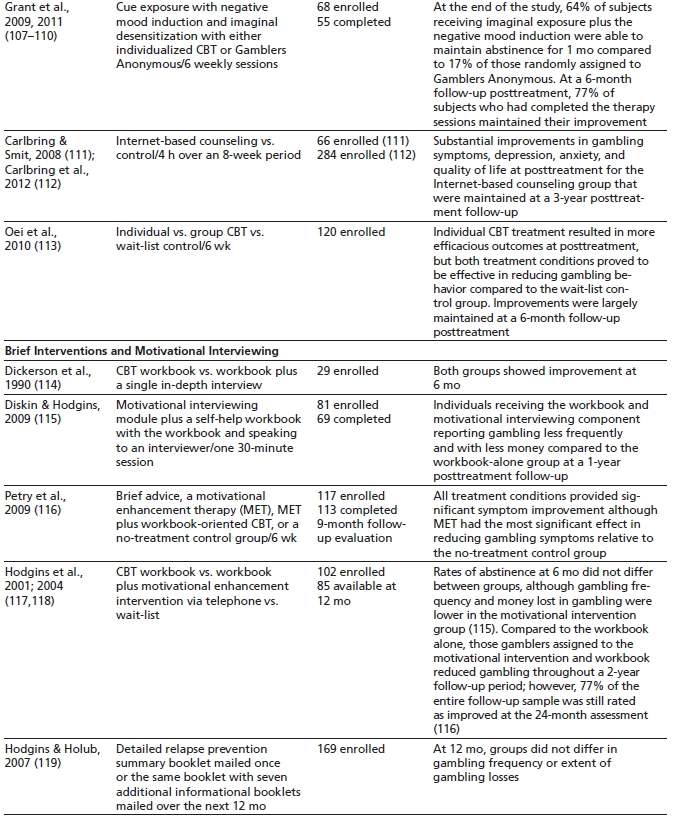

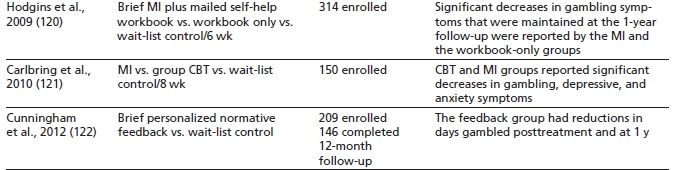

A variety of psychosocial treatments have been examined in controlled studies for the treatment of pathologic gambling (95). Cognitive strategies have traditionally included cognitive restructuring, psychoeducation, and irrational cognition awareness training. Behavioral approaches focus on developing alternate activities to compete with reinforc-ers specific to pathologic gambling as well as the identification of gambling triggers. See Table 39-1 for a summary of psychotherapeutic treatments.

TABLE 39-1 CONTROLLED PSYCHOLOGICAL TREATMENT TRIALS

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree