Chapter 10 Palliative medicine and symptom control

Introduction and general aspects

Palliative care is the active total care of patients who have advanced, progressive life-shortening disease. It is now recognized that palliative care should be based on needs not diagnosis: it is needed in many non-malignant diseases as well as in cancer (Box 10.1).

![]() Box 10.1

Box 10.1

Key components of a modern palliative care service

Management should be based on needs not diagnosis: the symptom burden of non-malignant disease often equals that of cancer

Management should be based on needs not diagnosis: the symptom burden of non-malignant disease often equals that of cancer

Care should be independent of the patients’ location and should help patients to remain at home if possible, avoiding unwanted admissions to hospital

Care should be independent of the patients’ location and should help patients to remain at home if possible, avoiding unwanted admissions to hospital

Rehabilitation for people with advanced disease

Rehabilitation for people with advanced disease

Bereavement care for people with pathological grief problems

Bereavement care for people with pathological grief problems

Telephone advice for other clinicians; disseminating palliative care knowledge

Telephone advice for other clinicians; disseminating palliative care knowledge

Teaching for clinicians, from undergraduate level to postgraduate life-long learning

Teaching for clinicians, from undergraduate level to postgraduate life-long learning

Importance of early assessment

If palliative care is seen only as relevant for the end-of-life phase, patients who have non-malignant disease are denied expert help for complex symptoms. Timely management of physical and psychosocial issues earlier in the course of disease prevents intractable problems later (Box 10.2).

![]() Box 10.2

Box 10.2

Problems arising when specialist palliative care (SPC) is delayed until the end-of-life

There is insufficient time to achieve good symptom control by combining non-pharmacological and pharmacological components

There is insufficient time to achieve good symptom control by combining non-pharmacological and pharmacological components

SPC services are deemed less acceptable by patient and family, being associated with ‘dying’ or ‘giving up’ or ‘giving in’ to illness

SPC services are deemed less acceptable by patient and family, being associated with ‘dying’ or ‘giving up’ or ‘giving in’ to illness

Psychological distress and physical symptoms become intractable and contribute to complex grief

Psychological distress and physical symptoms become intractable and contribute to complex grief

It becomes too late to adopt rehabilitative approach or teach/use non-pharmacological interventions that need a degree of training and patient motivation (e.g. cognitive behavioural approaches, mindfulness meditation, attendance at day therapy)

It becomes too late to adopt rehabilitative approach or teach/use non-pharmacological interventions that need a degree of training and patient motivation (e.g. cognitive behavioural approaches, mindfulness meditation, attendance at day therapy)

Symptom control

This section outlines the medical aspects of symptom control. Good palliative care integrates these with appropriate non-pharmacological approaches, including anxiety management and rehabilitation (see p. 489).

Pain

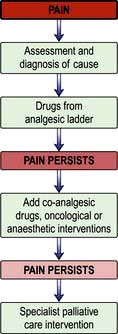

Pain is a feared symptom in cancer and at least two-thirds of people with cancer suffer significant pain. Pain has a number of causes, and not all pains respond equally well to opioid analgesics (Fig. 10.1). The pain is either related directly to the tumour (e.g. pressure on a nerve) or indirectly, for example due to weight loss or pressure sores. It may result from a co-morbidity such as arthritis. Emotional and spiritual distress may be expressed as physical pain (termed ‘opioid irrelevant pain’) or will exacerbate physical pain.

The term ‘total pain’ encompasses a variety of influences that contribute to pain:

Biological: the cancer itself, cancer therapy (drugs, surgery, radiotherapy)

Biological: the cancer itself, cancer therapy (drugs, surgery, radiotherapy)

Social: family distress, loss of independence, financial problems from job loss

Social: family distress, loss of independence, financial problems from job loss

Psychological: fear of dying, pain, or being in hospital; anger at dying or at the process of diagnosis and delays; depression from all of above

Psychological: fear of dying, pain, or being in hospital; anger at dying or at the process of diagnosis and delays; depression from all of above

Spiritual: fear of death, questions about life’s meaning, guilt.

Spiritual: fear of death, questions about life’s meaning, guilt.

The WHO analgesic ladder

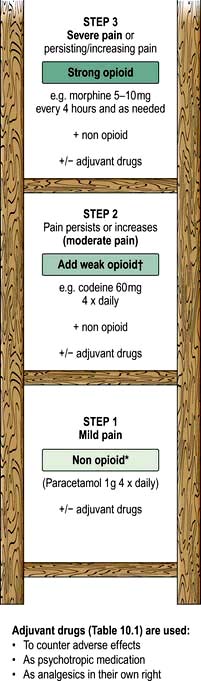

Most cancer pain can be managed with oral or commonly used transdermal preparations. The World Health Organization (WHO) cancer pain relief ladder guides the choice of analgesic according to pain severity (Fig. 10.2, Table 10.1).

Figure 10.2 WHO analgesic ladder for cancer and other chronic pain. Step 2 can be omitted, going to morphine immediately. Adjuvant drugs are listed in Table 10.1. *Opioids include all drugs with an action similar to morphine, i.e. binding to endogenous opioid receptors. †Continue NSAID/paracetamol regularly when opioid started.

Table 10.1 Commonly used adjuvant analgesics

| Drugs | Indication |

|---|---|

NSAIDs, e.g. diclofenac | Bone pain, inflammatory pain |

Anticonvulsants, e.g. gabapentin (600–2400 mg daily) or pregabalin (150 mg at start increasing up to 600 mg daily) | Neuropathic pain |

Tricyclic antidepressants, e.g. amitriptyline (10–75 mg daily) | Neuropathic pain |

Bisphosphonates, e.g. disodium pamidronate | Metastatic bone disease |

Dexamethasone | Neuropathic pain, inflammatory pain (e.g. liver capsule pain), headache from cerebral oedema due to brain tumour |

If regular use of optimum dosing (e.g. paracetamol 1 g × 4 daily for step 1) does not control the pain, then an analgesic from the next step of the ladder is prescribed. As pain is due to different physical aetiologies, an adjuvant analgesic may be needed in addition or instead, such as the tricyclic antidepressant amitriptyline for neuropathic pain (Table 10.1).

Strong opioid drugs

Side-effects

The most common side-effects are:

Nausea and vomiting: this can usually be managed or prevented with antiemetics (such as metoclopramide). Some antiemetics can be combined with an opioid, e.g. haloperidol or metoclopramide; always check compatibility data.

Nausea and vomiting: this can usually be managed or prevented with antiemetics (such as metoclopramide). Some antiemetics can be combined with an opioid, e.g. haloperidol or metoclopramide; always check compatibility data.

Constipation is common and should be anticipated with administration of a combination of stool softener (e.g. macrogols) and stimulants either separately or in one preparation Methyl naltrexone is a peripherally acting opioid receptor antagonist which is used if response to other laxatives is poor.

Constipation is common and should be anticipated with administration of a combination of stool softener (e.g. macrogols) and stimulants either separately or in one preparation Methyl naltrexone is a peripherally acting opioid receptor antagonist which is used if response to other laxatives is poor.

If side-effects are intractable, a change of opioid is often helpful.