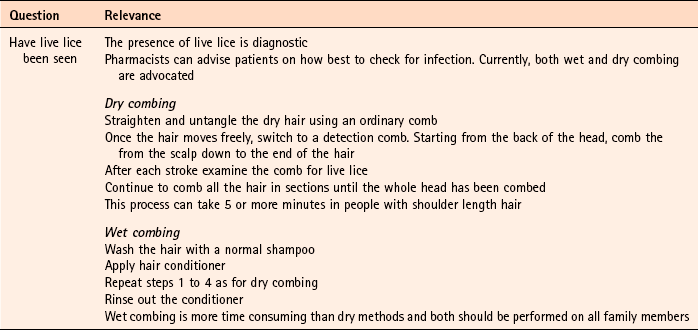

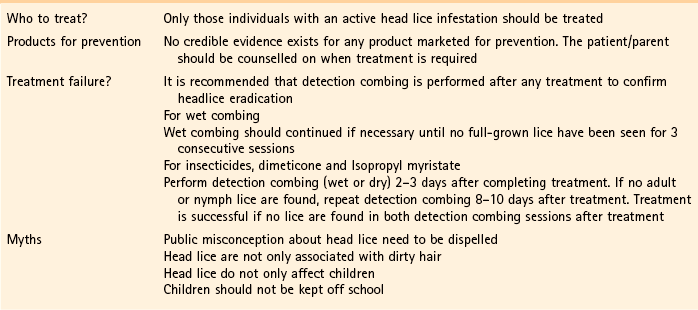

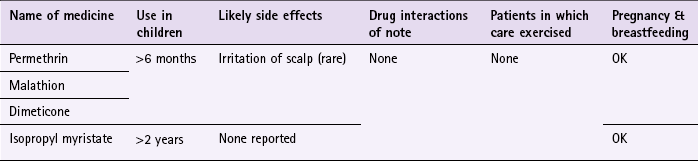

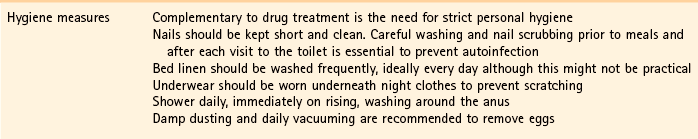

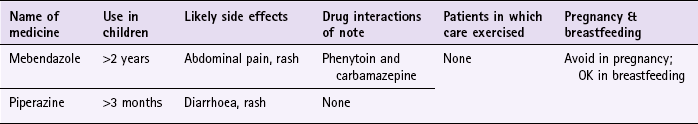

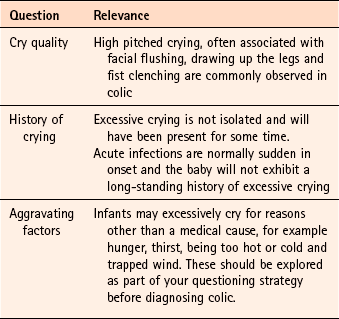

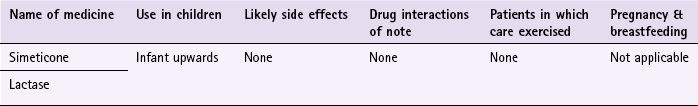

Chapter 9 Background Most parents will diagnose head lice themselves or be concerned that their child has head lice because of a recent local outbreak at school. Occasionally parents will also want to buy products to prevent their child contracting head lice. It is the role of the pharmacist to confirm a self-diagnosis and stop inappropriate sales of products. It should also be remembered that an itching scalp in children is not always due to head lice and other causes should be eliminated. Asking a number of symptom-specific questions should enable a diagnosis of head lice to be easily made (Table 9.1). Treatment options include insecticides, wet combing and physical agents. All treatments available in the UK have shown varying degrees of clinical effectiveness. It is however difficult to assess which treatment is most effective as very few comparative trials have been performed, and insecticidal resistance varies from region to region. No treatment is 100% effective and failure has been linked with poor adherence to each treatment regimen. Of the treatment approaches, insecticides have been most studied. These include malathion, permethrin, carbaryl and phenothrin – the latter two are now not commercially available. Cure rates of 70 to 80% are reported with insecticides in recent clinical trials, although resistance to insecticides is now a serious problem and appears to be increasing. Wet combing is an alternative treatment option, however, cure rates are reported to be only 40 to 60% with the low cure rates attributed to poor adherence (Roberts et al 2000; Hill et al 2005). Dimeticone is a recent introduction to the market, and is thought to work by coating the lice both internally and externally, which leads to disruption in water excretion causing the gut of the lice to rupture from osmotic stress (Burgess 2009). Its inclusion in treatment options seems to stem from 1 robust trial conducted by Burgess et al (2005). Dimeticone was compared against phenothrin with cure rates determined at days 9 and 14. Dimeticone was shown to have comparable cure rates to phenothrin (69% compared to 78%). The study has been criticised for using dry detection methods and using different detection days (days 5 and 12 as recommended by the department of health), however a further trial in 2007 supports the 2005 trial results. In the latter study, 4% dimeticone lotion, applied for 8 hours or overnight was compared to 0.5% malathion liquid applied for 12 hours or overnight. The results found dimeticone was significantly more effective than malathion, with 30/43 (70%) participants cured using dimeticone compared with 10/30 (33%) using malathion. Prescribing information relating to medicines for head lice reviewed in the section ‘Evidence base for over-the-counter medication’ is discussed and summarised in Table 9.2; useful tips relating to patients presenting with head lice are given in Hints and Tips Box 9.1. All products have to be used more than once; insecticides have to be repeated 7 days after first application (this is based on expert opinion, as the second application is intended to kill nymphs emerging from eggs that have survived the first application); wet combing every 4 days for at least 2 weeks. Coating agents, dimeticone and isopropyl myristate also have to be repeated after 7 days. Anon. Update on treatments for headlice. DTB. 2009;47:50–52. Burgess, IF. The mode of action of dimeticone 4% lotion against head lice, Pediculus capitis. BMC Pharmacol. 2009;9(1):3. Burgess, IF, Brown, CM, Lee, PN. Treatment of head louse infestation with 4% dimeticone lotion: randomised controlled equivalence trial. Br Med J. 2005;330:1423–1425. Hill, N, Moor, G, Cameron, MM, et al. Single blind, randomised, comparative study of the Bug Buster kit and over the counter pediculicide treatments against head lice in the United Kingdom. Br Med J. 2005;331:384–387. Roberts, RJ, Casey, D, Morgan, DA, et al. Comparison of wet combing with malathion for treatment of head lice in the UK: a pragmatic randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2000;356:540–544. Anon. Management of headlice in primary care. MeReC Bulletin. 2008;18(4):2–7. Burgess, IF, Brown, CM, Peock, S, et al. Head lice resistant to pyrethroid insecticides in Britain. Br Med J. 1995;311:752. Burgess, IF, Lee, PN, Matlock, G. Randomised, controlled, assessor blind trial Comparing 4% dimeticone lotion with 0.5% malathion liquid for head louse infestation. PLoS ONE. 2007;2(11):e1127. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0001127 Connolly, M. Current recommended treatments for headlice and scabies. The Prescriber. 2011;Jan:26–39. Dodd, CS. Interventions for treating headlice. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (Issue 4):2006. (Status withdrawn Issue 2, 2012, pending update) Threadworm (Enterobius vermicularis) Mebendazole and piperazine are available OTC for the treatment of threadworm. There is a large body of evidence to support the effectiveness of mebendazole in roundworm infections but for other worm infections, including threadworm, cure rates are lower. For threadworm, cure rates between 60 and 82% for single-dose treatment of mebendazole have been reported (Rafi et al 1997; Sorensen et al 1996). Prescribing information relating to medicines for threadworm reviewed in the section ‘Evidence base for over-the-counter medication’ is discussed and summarised in Table 9.3; useful tips relating to patients presenting with threadworm are given in Hints and Tips Box 9.2. Albonico, M, Smith, PG, Hall, A, et al. a randomized controlled trial comparing mebendazole and albendazole against Ascaris, Trichuris and hookworm infections. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1994;88:585–589. Anon. Merec Bulletin. Management of threadworms in primary care. 1998;18:11–13. Zaman, V. Other gut nematodes. In: Weatherall DJ, Ledingham JGG, Warrell DA, eds. Oxford textbook of medicine. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987. Colic There is no universally agreed definition of colic. A widely used definition of colic is that proposed by Wessel et al (1954) and has come to be known as the ‘rule of threes’. Wessel proposed that an infant could be considered to have colic if it cries for more than 3 hours a day for more than 3 days a week for more than 3 weeks. However, the definition by Wessel is arbitrary and few parents are willing to wait 3 weeks to see if the infant meets the criteria for colic. As a result the third criterion is usually dropped in the clinical setting. In addition, some authors have defined crying for as little as 90 minutes per day as excessive. Regardless of which definition is used, persistent crying is a cause of stress and anxiety to parents. Colic starts in the first few weeks of life and usually resolves by the age of 3 to 5 months. It can be difficult to determine if the baby has colic or is just excessively crying, as the diagnosis of the condition is dependent on qualitative descriptions. However, the term colic is often wrongly applied to any infant who cries more than usual. Asking a number of symptom specific questions should enable a diagnosis of colic to be made (Table 9.4). Prescribing information relating to dimethicone is discussed and summarised in Table 9.5; useful tips relating to colic are given in Hints and Tips Box 9.3.

Paediatrics

Head lice

Arriving at a differential diagnosis

Evidence base for over-the-counter medication

Practical prescribing and product selection

References

Evidence base for over-the-counter medication

Practical prescribing and product selection

Background

Prevalence and epidemiology

Arriving at a differential diagnosis

Practical prescribing and product selection

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Paediatrics