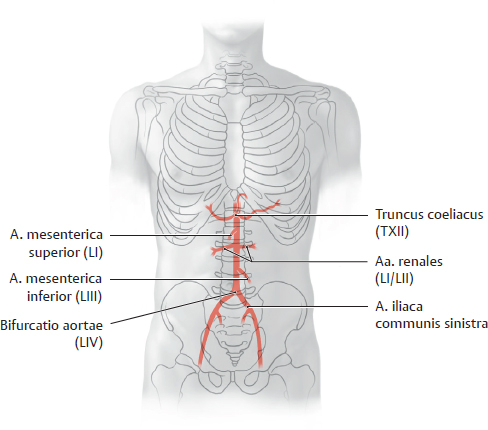

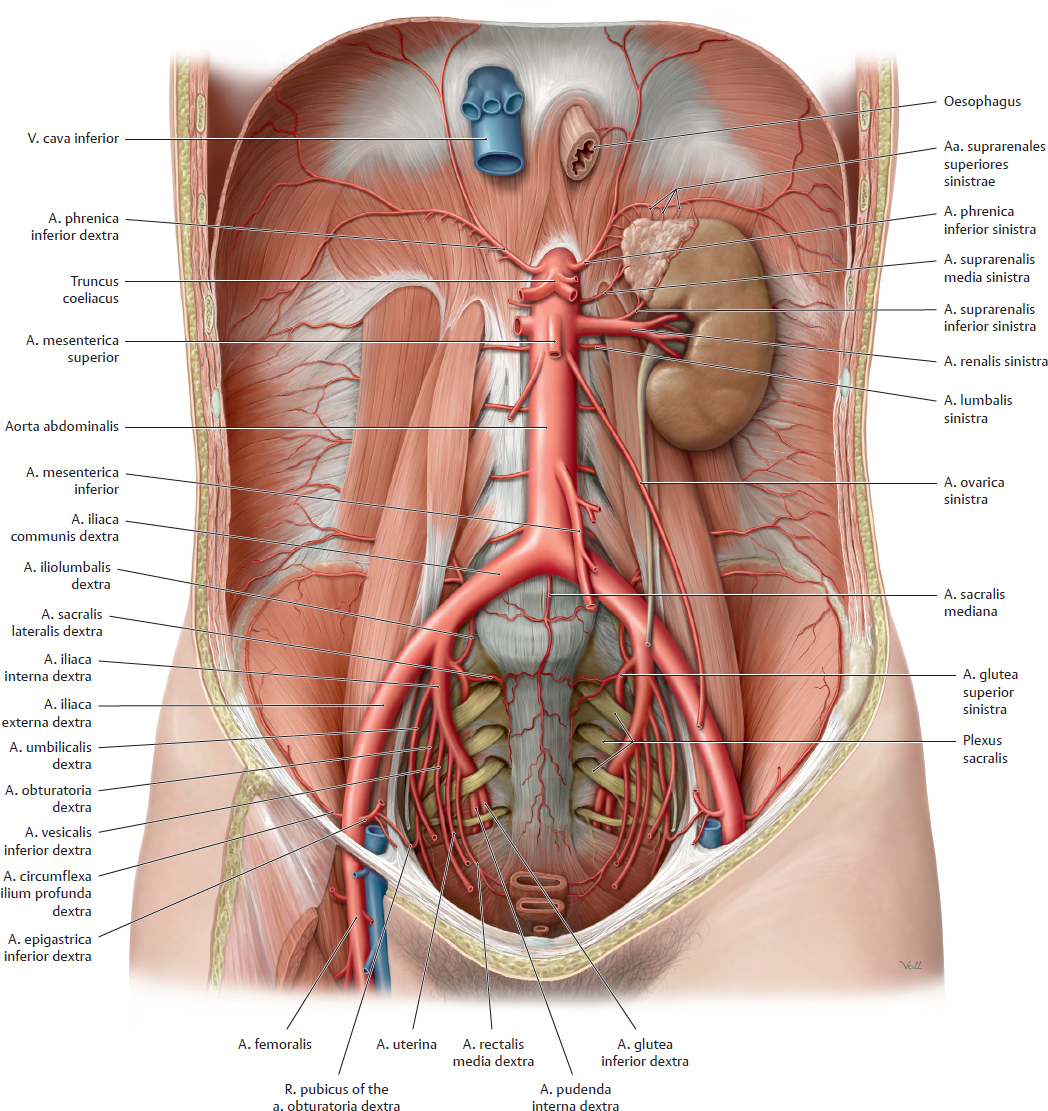

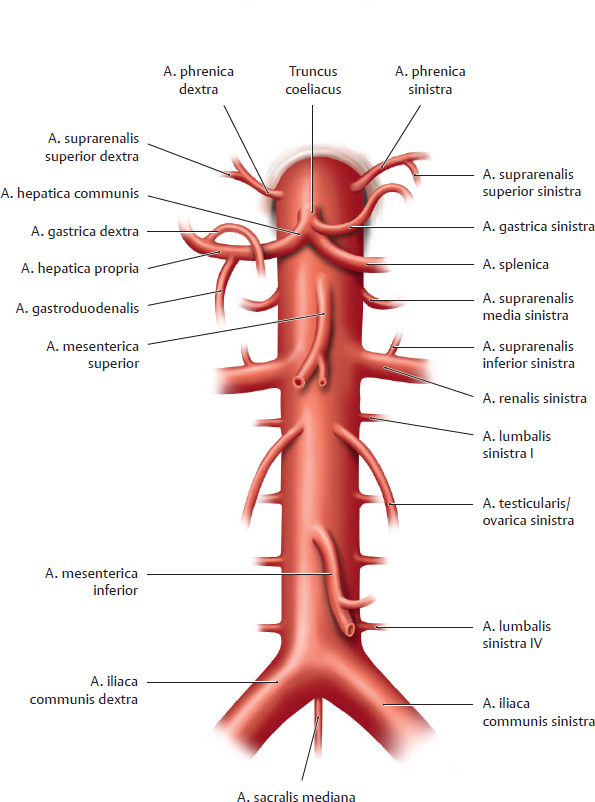

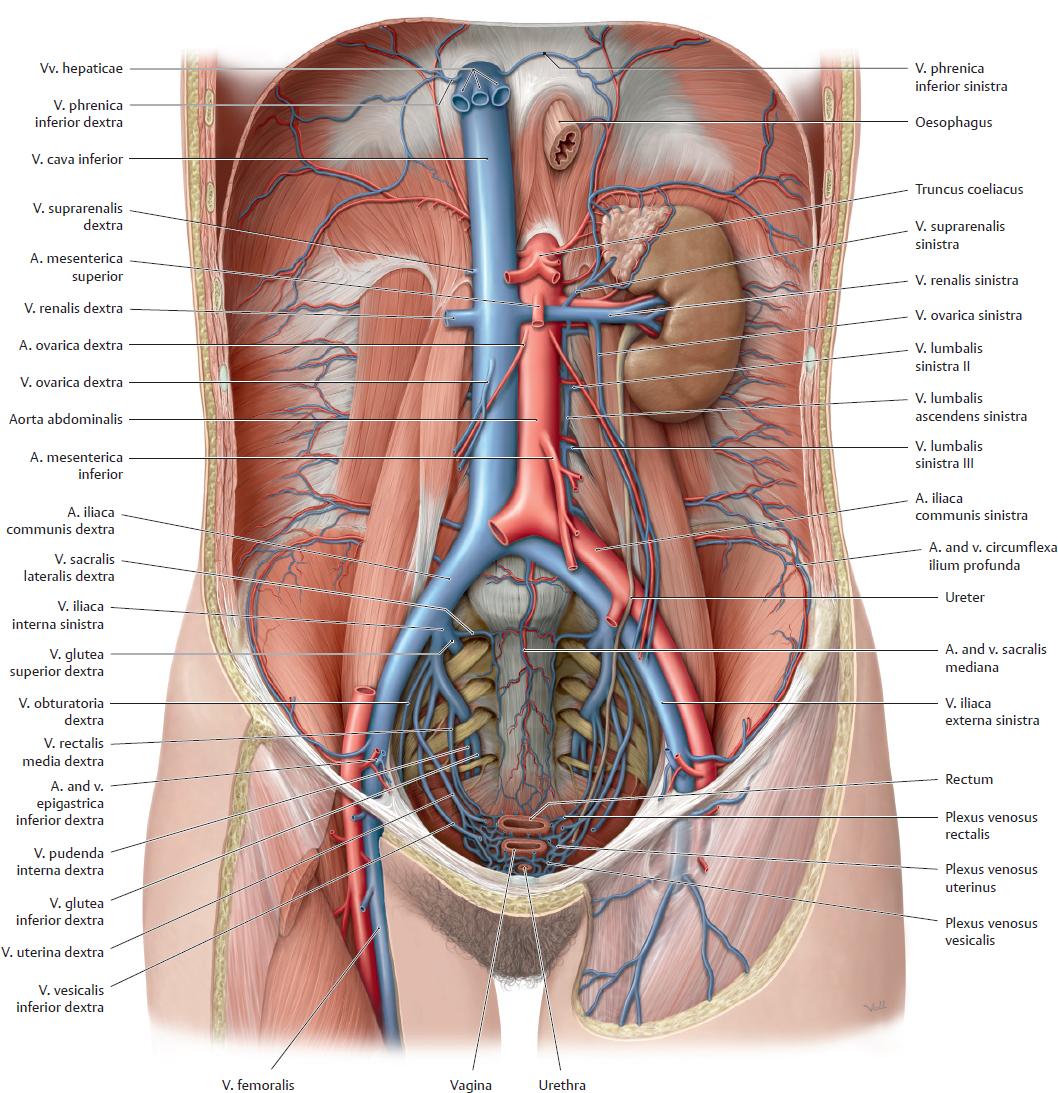

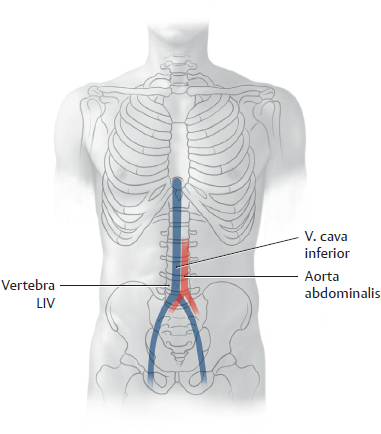

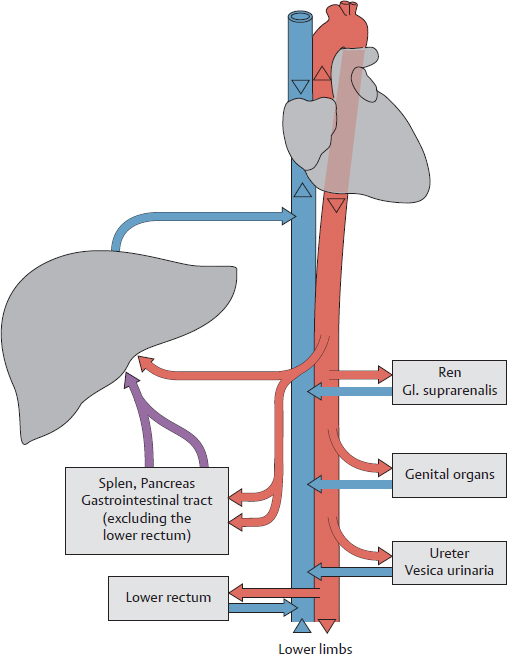

17. Overview of Neurovascular Structures A Overview of the aorta abdominalis and pelvic arteries (abdominal organs removed) Anterior view (female pelvis). The oesophagus has been pulled slightly inferiorly, and the peritoneum has been completely removed. The aorta abdominalis is the distal continuation of the aorta thoracica. It descends slightly to the left of the midline to approximately the level of the L 4 vertebra, as shown in B (or possibly to the L 5 vertebra in older individuals). There it divides into the paired aa. iliacae communes (bifurcatio aortae). The aa. iliacae communes divide further into the aa. iliacae internae and externae. The aorta abdominalis (see C) and its major branches give origin to various “subbranches” that supply the abdomen and pelvis (see D). B Projection of the aorta abdominalis and its major branches onto the columna vertebralis and pelvis Anterior view of the five major arterial trunks. The major branches of the aorta abdominalis can be identified in imaging studies based on their relationship to the vertebrae. C Sequence of branches from the aorta abdominalis D Functional groups of arteries that supply the abdomen and pelvis The branches of the aorta abdominalis and pelvic arteries can be divided into five broad functional groups (→ = give rise to). For details about the areas supplied by the unpaired branches see p. 205.

17.1 Branches of the Aorta Abdominalis: Overview and Paired Branches

Paired branches (and one unpaired branch) that supply the diaphragma, renes, gll. suprarenales, posterior abdominal wall, columna vertebralis, and gonadae ( see C) |

• Aa. phrenicae inferiores dextra and sinistra → Aa. suprarenales superiores dextra and sinistra • Aa. suprarenales mediae dextra and sinistra • Aa. renales dextra and sinistra → Aa. suprarenales inferiores dextra sinistra • Aa. testiculares (ovaricae) dextra and sinistra • Aa. lumbales dextrae and sinistrae (first through fourth) • A. sacralis mediana (with lowest aa. lumbales) |

One unpaired trunk that supplies the hepar, vesica biliaris, pancreas, splen, gaster, and duodenum (see C, pp. 205 and 257) |

• Truncus coeliacus with – A. gastrica sinistra – A. splenica – A. hepatica communis |

One unpaired trunk that supplies the intestinum tenue and intestinum crassum as far as the flexura coli sinistra (see C, pp. 205 and 261) |

• A. mesenterica superior |

One unpaired trunk that supplies the intestinum crassum from the flexura coli sinistra (see C, p. 205) |

• A. mesenterica inferior |

One indirect (see below) paired trunk that supplies the pelvis (see A, p. 205) |

• A. iliaca interna (from the a. iliaca communis, not directly from the aorta, hence an “indirect paired trunk”) |

17.2 Branches of the Aorta Abdominalis: Unpaired and Indirect Paired Branches

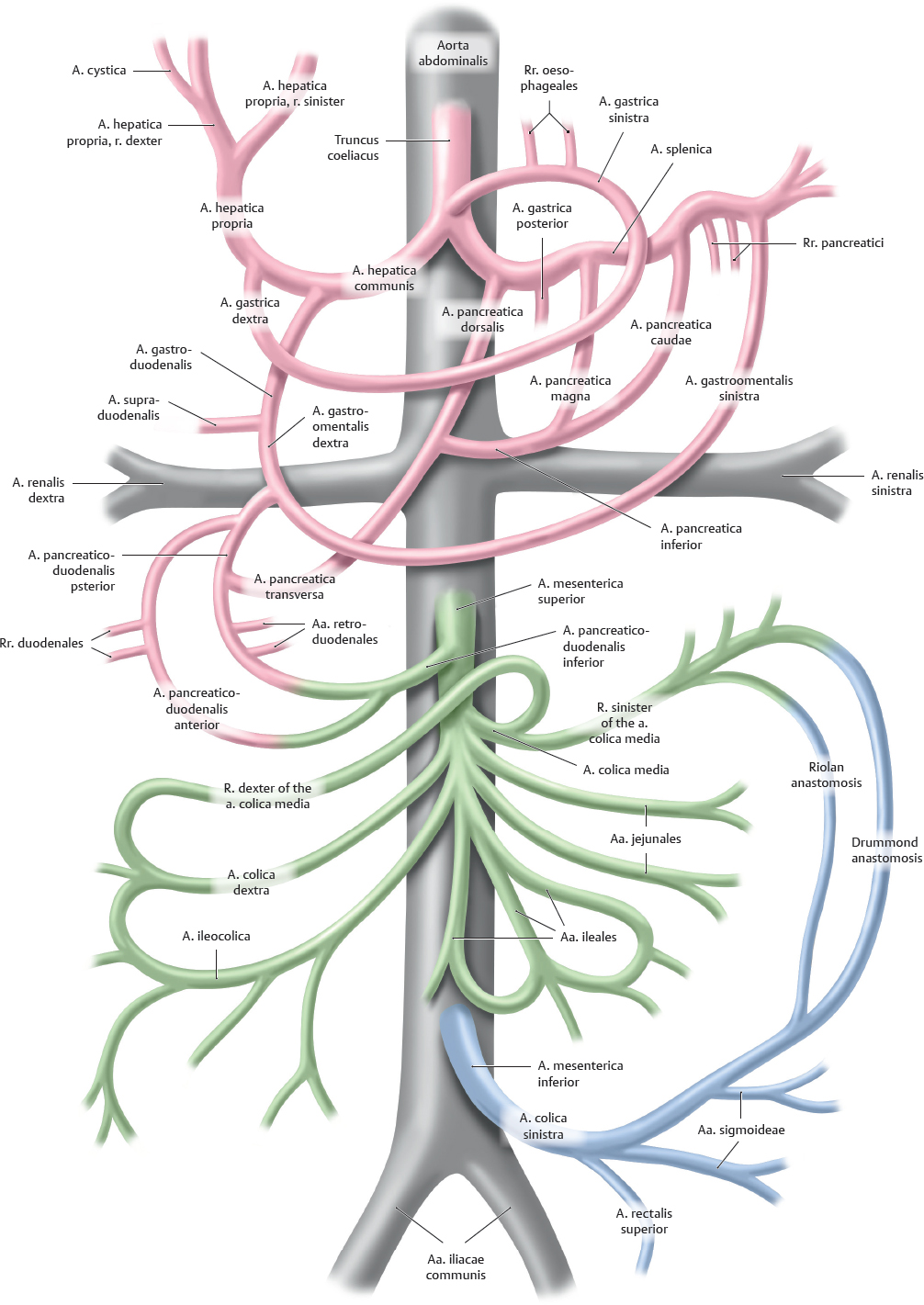

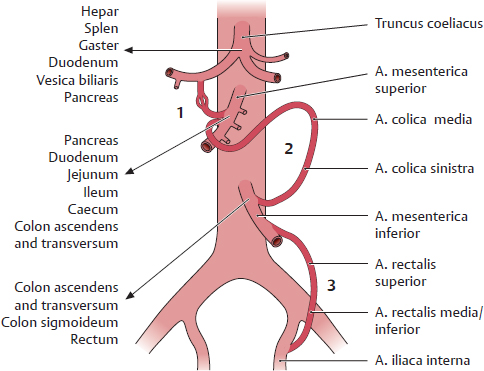

A Classification of arteries supplying the abdomen and pelvis

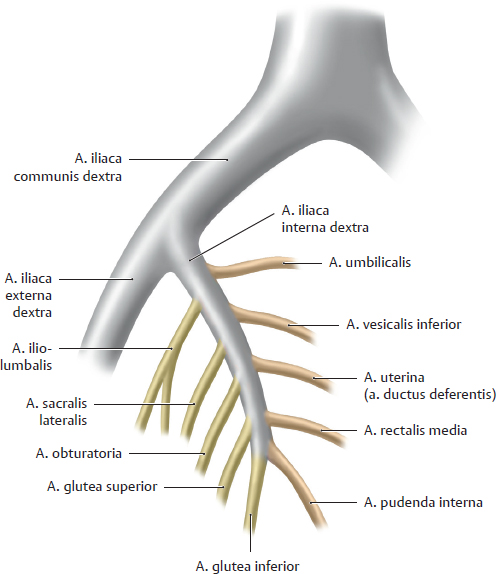

B Right a. iliaca communis with subbranches

The bifurcatio aortae is the point where the aorta abdominalis bifurcates into the two aa. iliacae communes, which give off multiple sub-branches that supply the viscera and pelvic walls (see D).

C Abdominal arterial anastomoses

1 Between the truncus coeliacus and a. mesenterica superior via the aa. pancreaticoduodenales

2 Between the aa. mesentericae superior and inferior (aa. colicae media and sinistra; Riolan and Drummond anastomoses, see A)

3 Between the a. mesenterica inferior and a. iliaca interna (a. rectalis superior and a. rectalis media or inferior)

These anastomoses are important in that they can function as collaterals, delivering blood to intestinal areas that have been deprived of their normal blood supply.

D Classification of the arteries supplying the abdomen and pelvis

The branches of the pars abdominalis aortae and the pelvic arteries can be divided into the five major areas they supply. For details about the area supplied by the paired branches see p. 203.

Note the anastomoses particularly between the unpaired trunks (see Fig. A and C).

One unpaired trunk that supplies the hepar, vesica biliaris, pancreas, splen, gaster, and duodenum (see A) | |

• Truncus coeliacus with – A. gastrica sinister – A. splenica | → Rr. oesophageales → A. gastroomentalis sinistra → Rr. pancreatici → A. caudae pancreatis → A. pancreatica magna → A. pancreatica dorsalis → A. pancreatica inferior → A. pancreatica transversa |

– A. hepatica communis | → A. hepatica propria → A. cystica → A. gastrica dextra → A. gastroduodenalis → A. supraduodenalis (inconstant branch of a. gastroduodenalis) → A. gastroomentalis dextra → Rr. duodenales → Aa. retroduodenales → A. pancreaticoduodenales superiores anterior and posterior |

One unpaired trunk that supplies the intestinum tenue and intestinum crassum as far as the flexura coli sinistra (see A) | |

• A. mesenterica superior | → A. pancreaticoduodenalis inferior → Aa. jejunales → Aa. ileales → A. ileocolica → A. colica dextra → A. colica media |

One unpaired trunk that supplies the intestinum crassum from the flexura coli sinistra (see A) | |

• A. mesenterica inferior | → A. colica sinistra → Aa. sigmoideae → A. rectalis superior |

One indirect (see below) paired trunk that supplies the pelvis (see B) | |

• A. iliaca interna (from the a. iliaca communis, not directly from the aorta, hence an “indirect paired trunk”) with branches that supply | |

| → A. umbilicalis → Aa. vesicales superiores → A. vesicalis inferior → uterina (A. ductus deferentis → A. rectalis media → A. pudenda interna |

The pelvic walls (parietal branches) | |

| → A. iliolumbalis → Aa. sacrales laterales → A. obturatoria → Aa. gluteae superior and inferior |

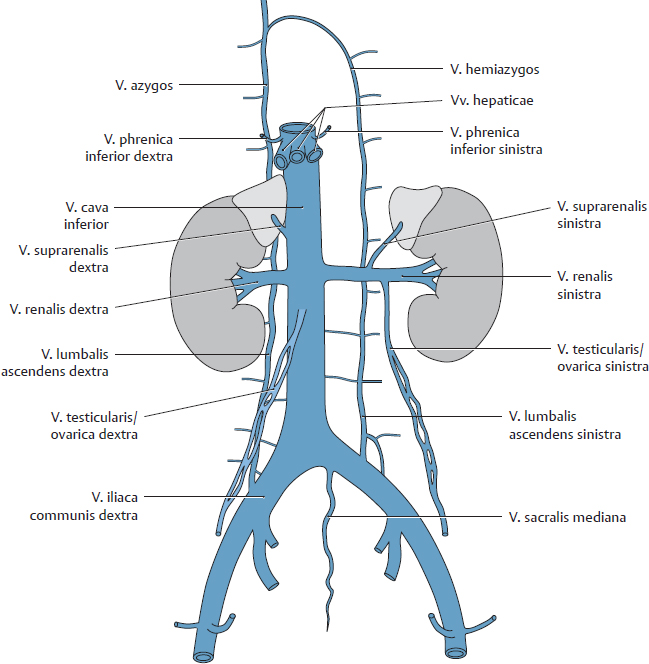

17.3 Inferior Vena Caval System

A Tributaries of the vena cava inferior in the posterior abdomen and pelvis

Anterior view of an opened female abdomen. All organs but the left ren and gl. suprarenalis have been removed, and the oesophagus has been pulled slightly inferiorly.

The v. cava inferior receives numerous tributaries that return venous blood from the abdomen and pelvis (and, of course, from the lower limbs), analogous to the distribution of the paired abdominal aortic branches in this region. The v. cava inferior is formed by the union of the two vv. iliacae communes at the approximate level of the L 5 vertebra (see C), behind and slightly inferior to the bifurcatio aortae.

Note the special location of the left v. renalis and its risk of compression by the a. mesenterica superior (see p. 261): The left v. renalis passes in front of the aorta abdominalis but behind the a. mesenterica superior. Veins in the male pelvis are described on p. 339. The veins in the pelvis have numerous variants. For example, the tributaries of the v. iliaca interna are frequently multiple (unlike those shown above) but unite to form a single trunk before entering the v. iliaca (see also p. 341).

B Tributaries of the vena cava inferior

The difference in the venous drainage of the right and left renes is displayed more clearly here than in A. The continuity of the right v. lumbalis ascendens with the v. azygos is also shown.

Direct tributaries return venous blood directly to the v. cava inferior without passing through an intervening capillary bed. Direct tributaries drain the following organs:

• The diaphragma, abdominal wall, renes, gll. suprarenales, testes/ovaria, and hepar

• For the pelvis (via the v. iliaca communis) from the pelvic wall and floor, uterus, tubae uterinae, vesica urinaria, ureteres, accessory sex glands, lower rectum, and lower limb.

Indirect tributaries return blood that has passed through the capillary bed of the hepar via the hepatic portal system (see p. 209). The following organs have indirect tributaries:

• The splen

• The organs of the digestive tract: pancreas, duodenum, jejunum, ileum, caecum, colon, and upper rectum

Note: Venous blood from the v. cava inferior may drain through the vv. lumbales ascendentes into the v. azygos or hemiazygos and thence to the v. cava superior. Thus a connection between the two vv. cavae exists on the posterior wall of the abdomen and thorax: a cavocaval or intercaval anastomosis. The location and significance of cavocaval anastomoses are discussed on p. 210. Frequently an anastomosis exists between the v. suprarenalis and v. phrenica inferior (not shown here, see A) on the left side of the body.

C Projection of the vena cava inferior onto the columna vertebralis

The v. cava inferior ascends on the right side of the aorta abdominalis and pierces the diaphragma at the foramen venae cavae located at the T 8 level. The vv. iliacae communes unite at the L 5 level to form the v. cava inferior (see also A).

D Direct tributaries of the vena cava inferior

• Right and left vv. phrenicae inferiores

• Vv. hepaticae

• V. suprarenalis dextra

• Right and left vv. renales at the L 1/L 2 level (the v. testicularis/ovarica sinistra and v. suprarenalis sinistra terminate in the left v. renalis)

• Vv. lumbales

• V. testicularis/ovarica dextra

• Vv. iliacae communes (L 5 level)

• V. sacralis mediana (often terminates in the left v. iliaca communis)

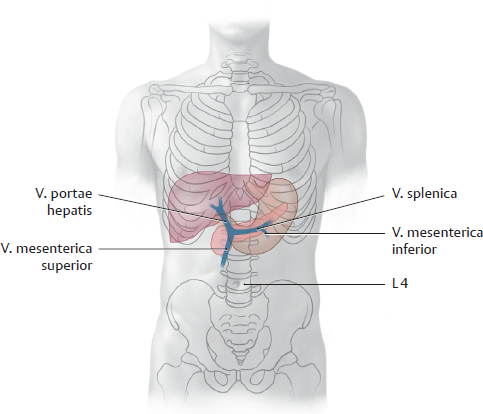

17.4 Portal Venous System (Vena Portae Hepatis)

A The portal venous system in the abdomen

The arterial blood supply and venous drainage of the abdominal and pelvic organs differ in their functional organization: While they derive their arterial blood supply entirely from the aorta abdominalis or one of its major branches, venous drainage is accomplished by one of two different venous systems:

1. Organ veins that drain directly or indirectly (via the vv. iliacae) into the v. cava inferior, which then returns the blood to the right heart (see also p. 206);

2. Organ veins that first drain directly or indirectly (via the vv. mesentericae or v. splenica) into the v. portae hepatis—and thus to the hepar—before the blood enters the v. cava inferior and returns to the right cor.

The first pathway serves the urinary organs, gll. suprarenales, genital organs, and the walls of the abdomen and pelvis. The second pathway serves the organs of the digestive system (hollow organs of the gastrointestinal tract, pancreas, vesica biliaris) and the splen (see D). Only the lower portions of the rectum are exempt from this pathway and drain directly through the vv. iliacae to the v. cava inferior. This (re) routing of venous blood through the hepatic portal system ensures that the organs of the digestive tract deliver their nutrient-rich blood to the hepar for metabolic processing before it is returned to the cor. It also provides a route by which elements of degenerated red blood cells can be conveyed from the splen to the hepar. Thus, the v. portae hepatis functions to deliver blood to the hepar to support metabolism. This contrasts with the a. hepatica propria, which supplies the hepar with oxygen and other nutrients. Anastomoses may develop between the portal venous system and vena caval system (portacaval anastomosis) and function as collateral pathways in certain diseases (see p. 210).