50

Opportunistic Mycoses

CHAPTER CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

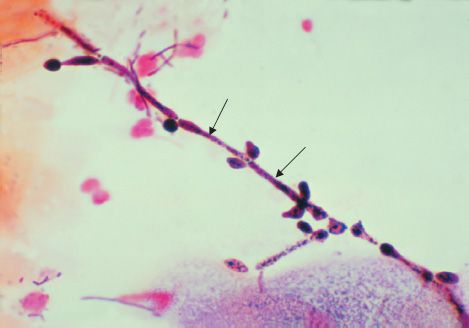

Opportunistic fungi fail to induce disease in most immunocompetent persons but can do so in those with impaired host defenses. There are five genera of medically important fungi: Candida, Cryptococcus, Aspergillus, Mucor, and Rhizopus. Important features of the opportunistic fungal diseases are described in Table 50–1.

CANDIDA

Diseases

Candida albicans, the most important species of Candida, causes thrush, vaginitis, esophagitis, diaper rash, and chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis. It also causes disseminated infections such as right-sided endocarditis (especially in intravenous drug users), bloodstream infections (candidemia), and endophthalmitis. Infections related to indwelling intravenous and urinary catheters are also important.

Properties

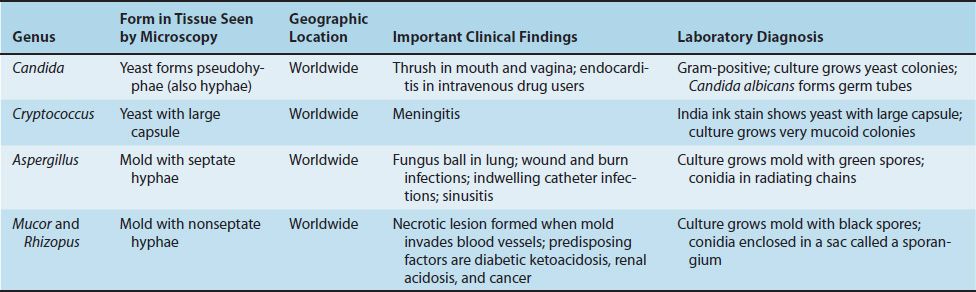

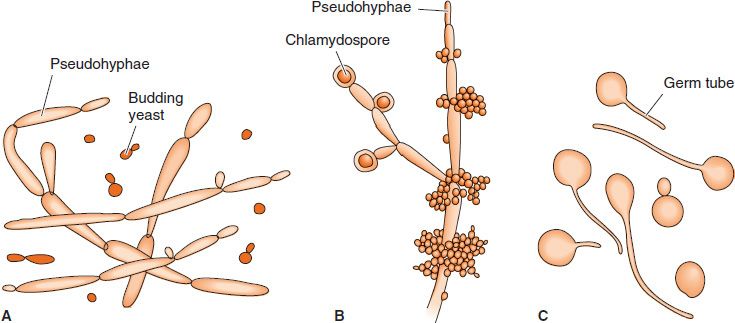

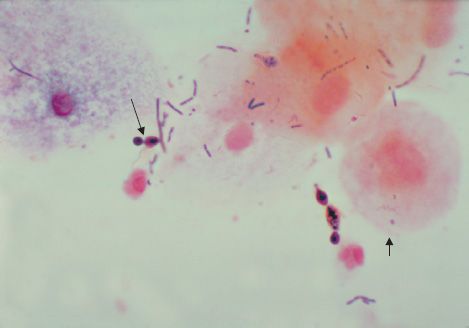

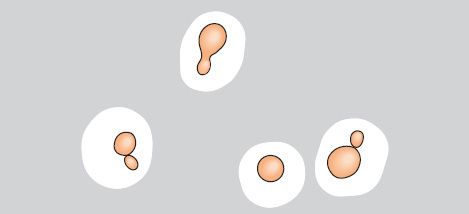

C. albicans is an oval yeast with a single bud (Figures 50–1 and 50–2). It is part of the normal flora of mucous membranes of the upper respiratory, gastrointestinal, and female genital tracts. In tissues it may appear as yeasts or as pseudohyphae (Figures 50–1 and 50–3). Pseudohyphae are elongated yeasts that visually resemble hyphae but are not true hyphae. True hyphae are also formed when C. albicans invades tissues.

FIGURE 50–1 Candida albicans. A: Budding yeasts and pseudohyphae in tissues or exudate. B: Pseudohyphae and chlamydospores in culture at 20°C. C: Germ tubes at 37°C. (Reproduced with permission from Brooks GF et al. Medical Microbiology. 20th ed. Originally published by Appleton & Lange. Copyright 1995 McGraw-Hill.)

FIGURE 50–2 Candida albicans—yeast. Long arrow points to a budding yeast. Short arrow points to the outer membrane of a vaginal epithelial cell. In this Gram-stained specimen, various bacteria that are part of the normal flora of the vagina can be seen. (Figure courtesy of Dr. S. Brown, Public Health Image Library, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.)

FIGURE 50–3 Candida albicans—pseudohyphae. Two arrows point to pseudohyphae of Candida albicans. (Figure courtesy of Dr. S. Brown, Public Health Image Library, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.)

Carbohydrate fermentation reactions differentiate it from other species (e.g., Candida tropicalis, Candida parapsilosis, Candida krusei, and Candida glabrata).

Transmission

As a member of the normal flora, C. albicans is already present on the skin and mucous membranes. The presence of C. albicans on the skin predisposes to infections involving instruments that penetrate the skin, such as needles (intravenous drug use) and indwelling catheters.

Pathogenesis & Clinical Findings

When local or systemic host defenses are impaired, disease may result. Overgrowth of C. albicans in the mouth produces white patches called thrush (Figure 50–4). (Note that thrush is a pseudomembrane, a term that is defined in Chapter 7 on page 39.) Vaginitis with itching and discharge is favored by high pH, diabetes, or use of antibiotics. Antibiotics suppress the normal flora Lactobacillus, which keep the pH low. As a result, the pH rises, which favors the growth of Candida.

FIGURE 50–4 Candida albicans—thrush in mouth. Note whitish plaques on tongue. (Courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD, and The Color Atlas of Family Medicine.)

Skin invasion occurs in warm, moist areas, which become red and weeping. Fingers and nails become involved when repeatedly immersed in water; persons employed as dishwashers in restaurants are commonly affected. Thickening or loss of the nail can occur. Diaper rash in infants occurs when wet diapers are not changed promptly (Figure 50–5).

FIGURE 50–5 Candida albicans—diaper rash. Note extensive area of inflammation in perineal region. (Reproduced with permission from Wolff K, Johnson R. Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas & Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. 6th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2009. Copyright © 2009 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc.)

In immunosuppressed individuals, Candida may disseminate to many organs or cause chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis (CMC). CMC is a prolonged infection of the skin, oral and genital mucosa, and nails that occurs in individuals deficient in T-cell immunity. Patients with mutations in the gene encoding interleukin-17 (IL-17) and the receptor for IL-17 are predisposed to CMC. After organ transplantation, patients receiving immunosuppressive drugs to prevent rejection are predisposed to invasive Candida infections.

Intravenous drug abuse, indwelling intravenous catheters, and hyperalimentation also predispose to disseminated candidiasis, especially right-sided endocarditis and endophthalmitis (infection within the eye). Candida esophagitis, often accompanied by involvement of the stomach and small intestine, is seen in patients with leukemia and lymphoma. Subcutaneous nodules are often seen in neutropenic patients with disseminated disease. C. albicans is the most common species to cause disseminated disease in these patients, but C. tropicalis and C. parapsilosis are important pathogens also.

Laboratory Diagnosis

In exudates or tissues, budding yeasts and pseudohyphae appear gram-positive and can be visualized by using calcofluor-white staining. In culture, typical yeast colonies are formed that resemble large staphylococcal colonies. Germ tubes form in serum at 37°C, which serves to distinguish C. albicans from most other Candida species (Figure 50–1). Chlamydospores are typically formed by C. albicans but not by other species of Candida. Serologic testing is rarely helpful.

Skin tests with Candida antigens are uniformly positive in immunocompetent adults and are used as an indicator that the person can mount a cellular immune response. A person who does not respond to Candida antigens in the skin test is presumed to have deficient cell-mediated immunity. Such a person is anergic, and other skin tests cannot be interpreted. Thus if a person has a negative Candida skin test, a negative purified protein derivative (PPD) skin test for tuberculosis could be a false-negative result.

Treatment & Prevention

The drug of choice for oropharyngeal or esophageal thrush is fluconazole. Itraconazole and voriconazole are also effective. Caspofungin or micafungin can also be used for esophageal candidiasis. Treatment of skin infections consists of topical antifungal drugs (e.g., clotrimazole or nystatin). Candida vaginitis is treated either with topical (intravaginal) azole drugs, such as clotrimazole or miconazole, or with oral fluconazole. Mucocutaneous candidiasis can be controlled by ketoconazole.

Treatment of disseminated candidiasis consists of either amphotericin B or fluconazole. Liposomal amphotericin B should be used in patients with preexisting kidney damage.

These two drugs can be used with or without flucytosine. Treatment of candidal infections with antifungal drugs should be supplemented by reduction of predisposing factors. Strains of C. albicans resistant to azole drugs have emerged in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) receiving long-term prophylaxis with fluconazole.

Certain candidal infections (e.g., thrush) can be prevented by oral clotrimazole troches, buccal miconazole tablets, or nystatin “swish and swallow.” Fluconazole is useful in preventing candidal infections in high-risk patients, such as those undergoing bone marrow transplantation and premature infants. Micafungin can also be used. There is no vaccine.

CRYPTOCOCCUS

Disease

Cryptococcus neoformans causes cryptococcosis, especially cryptococcal meningitis. Cryptococcosis is the most common, life-threatening invasive fungal disease worldwide. It is especially important in AIDS patients. Another species, Cryptococcus gattii, causes human disease less frequently than C. neoformans.

Properties

C. neoformans is an oval, budding yeast surrounded by a wide polysaccharide capsule (Figures 50–6 and 50–7). It is not dimorphic. Note that this organism forms a narrow-based bud, whereas the yeast form of Blastomyces dermatitidis forms a broad-based bud.

FIGURE 50–6 Cryptococcus neoformans. India ink preparation shows budding yeasts with a wide capsule. India ink forms a dark background; it does not stain the yeast itself. (Reproduced with permission from Brooks GF et al. Medical Microbiology. 20th ed. Originally published by Appleton & Lange. Copyright 1995 McGraw-Hill.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree