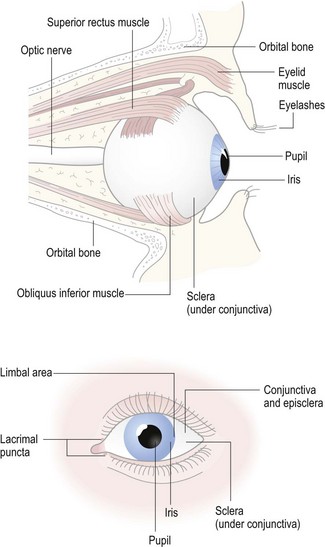

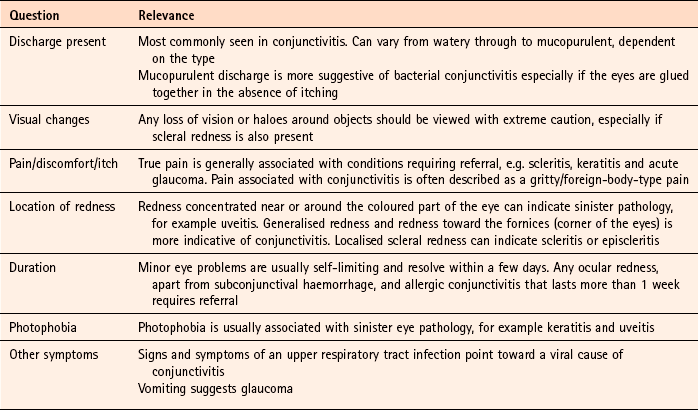

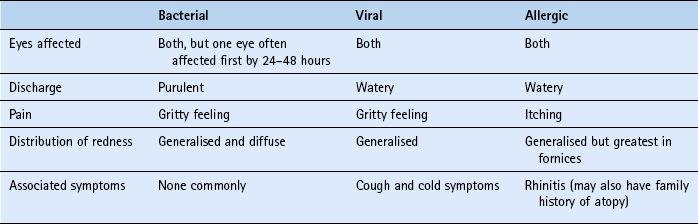

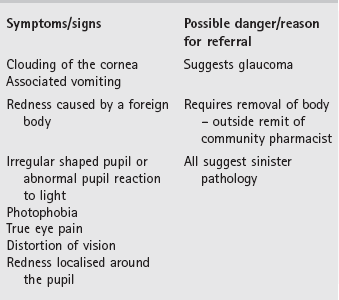

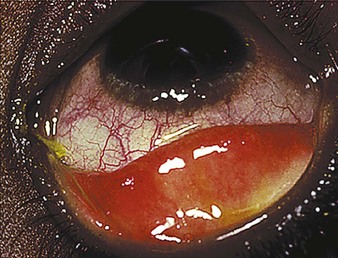

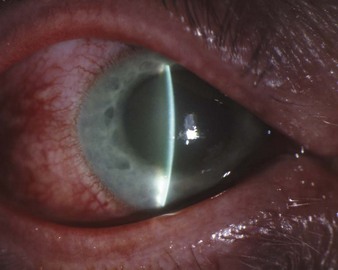

Chapter 2 Background A basic understanding of the main eye structures is useful to help pharmacists assess the nature and severity of the presenting complaint. Figure 2.1 highlights the principal eye structures. • Next, ask the patient to look straight ahead. This allows you to view the pupil, cornea and sclera. • Then, gently pull down the lower lid and ask the patient to look upwards and to both the left and the right. • Next, gently lift the upper lid and ask the patient to look downwards and to both the left and right. • These two steps enable you to examine the conjunctiva. • Now ask the patient to look directly into a near light and then to look back at you. This is best performed using a pen-torch. This enables you to examine the reaction of the pupils to light. Any abnormal pupil reaction in the presence of ocular symptoms should always be treated seriously. • You should finally assess the visual acuity of the patient by asking the patient to read small print with the affected eye. If the patient shows any difficulty in reading small print this should be viewed with caution. (Snellen charts – standard charts used to assess visual acuity – are not usually available in a community pharmacy). Red eye is a presenting complaint of both serious and non-serious causes of eye pathology. Community pharmacists must be able to differentiate between those conditions that can be managed and those that need referral. Table 2.1 depicts those conditions which the pharmacist may see. Table 2.1 Causes of red eye and their relative incidence in community pharmacy Redness of the eye can occur alone or present with accompanying symptoms of pain, discomfort, discharge and loss of visual acuity. Along with an examination of the eye a number of eye specific questions should always be asked of the patient to aid in diagnosis (Table 2.2). The overwhelming majority of patients presenting to the pharmacy with red eye will have some form of conjunctivitis. Each of the three common types of conjunctivitis has similar but varying symptoms. Each presents with the main symptoms of redness, discharge and discomfort. Table 2.3 and Figures 2.2, 2.3 and 2.4 highlight the similarities and differences in the classical presentations of the three conditions. Fig. 2.2 Bacterial conjunctivitis. Reproduced from David A. Palay and Jay H. Krachmer, 2005, Primary Care Ophthalmology, 2nd edition, Elsevier Mosby, with permission. Fig. 2.3 Viral conjunctivitis. Reproduced from Joseph W Sowka OD, Andrew S Gurwood OD and Alan Kabat OD, Handbook of Ocular Disease Management, Jobson Publishing, with permission. Subconjunctival haemorrhage: The rupture of a blood vessel under the conjunctiva causes subconjunctival haemorrhage. A segment of, or even the whole eye will appear bright red (Fig. 2.5). It occurs spontaneously but can be precipitated by coughing, straining or lifting. The suddenness of symptoms and the brightness of the blood invariably means patients present very soon after they have noticed the problem. There is no pain and the patient should be reassured that symptoms will resolve in 10 to 14 days without treatment. However, a patient with a history of trauma should be referred to exclude ocular injury. Episcleritis: The episclera lies just beneath the conjunctiva and adjacent to the sclera. If this becomes inflamed the eye appears red, which is segmental affecting only part of the eye (Fig. 2.6). The condition affects only one eye in the majority of cases and is usually painless or a dull ache might be present. It is more commonly seen in young women and is usually self-limiting resolving in 2 to 3 weeks, but it can take 6 to 8 weeks before symptoms resolve. Episcleritis is one of those conditions, like subconjunctival haemorrhage, that typically looks worse than it is. Scleritis: Inflammation of the sclera is much less common than episcleritis. It is often associated with autoimmune diseases, for example in 20% of cases the patient has rheumatoid arthritis. It presents similarly to episcleritis but pain is a predominant feature as is blurred vision. Eye movement can worsen pain. Scleritis also tends to affect older people (mean presentation age in the early 50s). Discharge is rare or absent in both episcleritis and scleritis. Keratitis (corneal ulcer): Inflammation of the cornea often results from recent trauma (e.g. eye abrasion) or administration of long-term steroid drops. Over wear of soft contact lenses has also been implicated in causing keratitis. Pain, which can be very severe, is a prominent feature. The patient usually complains of photophobia and loss of visual acuity accompanied with a watery discharge. Redness of the eye tends to be worse around the iris. Immediate referral to a medical practitioner is needed as loss of sight is possible if left untreated. Uveitis (iritis): Uveitis describes inflammation involving the uveal tract (iris, ciliary body and choroids). The likely cause is an antigen-antibody reaction, which can occur as part of a systemic disease such as rheumatoid arthritis or ulcerative colitis. Photophobia and pain are prominent features along with redness and watering of the eye. Usually, only one eye is affected and the redness is often localised to the limbal area (known as the ciliary flush). On examination, the pupil will appear irregular shaped, constricted or fixed (Fig. 2.7). The patient might also complain of impaired reading vision. Immediate referral to a medical practitioner is needed. Acute closed-angle glaucoma: There are two main types of glaucoma: • simple chronic open-angle glaucoma, which does not cause pain • acute closed-angle glaucoma, which can present with a painful red eye. The latter requires immediate referral to the GP or even casualty. It is due to inadequate drainage of aqueous fluid from the anterior chamber of the eye, which results in an increase in intraocular pressure. The onset can be very quick and characteristically occurs in the evening. The eye appears red and may be cloudy (Fig. 2.8). Vision is blurred and the patient might also notice haloes around lights. Vomiting is often experienced due to the rapid rise in intraocular pressure. As it is such a painful condition, patients are unlikely to present to the community pharmacist. Fig. 2.8 Acute angle glaucoma. Reproduced from Jack J Kanski, 2007, Clinical Ophthalmology: A Systematic Approach, 6th edition, Butterworth Heinemann, with permission. Figure 2.9 can be used to help differentiation between serious and non-serious red eye conditions. Rose et al (The Lancet 2005) questioned whether antibiotics were needed in children as no significant difference was seen in the cure rate after 7 days; 86% of the children were clinically cured in the antibiotic group compared with 83% in the placebo group. The authors concluded that antibiotics were not needed in children. The most recent Cochrane review (Sheikh & Hurwitz 2006) concluded that: • bathe the eyelids with lukewarm water to remove any discharge • tissues should be used to wipe the eyes and thrown away immediately • avoid wearing contact lenses until symptoms have resolved • regular hand washing and avoid sharing pillows and towels. Avoidance of the allergen will, in theory, result in control of symptoms. However, total avoidance is almost impossible and the use of prophylactic medication is usually advocated. The evidence base for mast cell stabilisers, antihistamines and sympathomimetics is discussed in Chapter 1 (page 27). Prescribing information relating to medication for red eye reviewed in the section ‘Evidence base for over-the-counter medication’ is discussed and summarised in Table 2.4 and useful tips relating to treatment are given in Hints and Tips Box 2.1. Mast cell stabilisers (sodium cromoglicate): Intraocular sodium cromoglicate (e.g. Opticrom Allergy, Optrex Allergy) is a prophylactic agent and therefore has to be given continuously whilst exposed to the allergen. One or two drops should be administered in each eye four times a day. Although no minimum age is stated for their use, data on file from Sanofi Aventis (Opticrom Allergy) show it can be used from children over the age of six. Clinical experience has shown it to be safe in pregnancy and expert opinion considers sodium cromoglicate to be safe in breastfeeding. It has no drug interactions and can be given to all patient groups. Instillation of the drops may cause a transient blurring of vision.

Ophthalmology

General overview of eye anatomy

The eye examination

Red eye

Arriving at a differential diagnosis

Incidence

Cause

Most likely

Bacterial or allergic conjunctivitis

Likely

Viral conjunctivitis, subconjunctival haemorrhage

Unlikely

Episcleritis, scleritis, keratitis, uveitis

Very Unlikely

Acute closed angle glaucoma

Clinical features of conjunctivitis

Conditions to eliminate

Unlikely causes

Very unlikely causes

Evidence base for over-the-counter medication

Summary of advice for patients

Allergic conjunctivitis

Practical prescribing and product selection

Products for bacterial conjunctivitis

Propamidine isethionate 0.1% (Brolene and Golden Eye Drops) and Dibromopropamidine isethionate 0.15% (Golden Eye Ointment)

Products for allergic conjunctivitis

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree