Chapter Forty-Seven. Operative delivery

Introduction

The RCOG (2005) further reiterate that the operator must have the appropriate skill and knowledge not only to be able to conduct the instrumental delivery but also to be able to manage any complications, should they occur. They advocate that obstetricians should also have previous experience of vaginal deliveries prior to training in operative procedures. Vaginal assisted deliveries should be undertaken for four basic reasons (Chamberlain & Steer 1999):

1. Fetal or maternal distress in second stage of labour.

2. Lack of advancement in second stage of labour.

3. Control of the after-coming head in a breech delivery.

4. Prophylactic shortening of second stage in, for example, heart disease.

The only absolute indications for caesarean section (CS) are cephalopelvic disproportion and major degrees of placenta praevia. Other indications demand a judgement by the obstetrician that the risk of vaginal delivery exceeds the risk of the operation or that the mother’s perception is that it does (Chamberlain & Steer 1999).

Forceps delivery

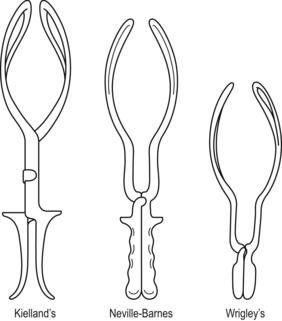

Obstetric forceps have been known and utilised in difficult deliveries since their invention by the Chamberlen family in the 17th century (Dunn 1999). Since then, there have been attempts to modify and improve their effectiveness and safety, leading to a variety of instruments available for use in different obstetric situations (Fig. 47.1). Obstetric forceps consist of two blades, each with a handle and a shank. The blades are marked ‘L’ left or ‘R’ right, according to the side of the mother’s pelvis in which they lie when applied. There may be a locking or traction device incorporated into the mechanism (Hamilton 2003a). Whatever the variation in shape, two considerations are important leading to the addition of pelvic and cephalic curves:

• The shape and size of the fetal head.

• The curve, shape and size of the bony pelvis.

|

| Figure 47.1 Obstetric forceps. (From Henderson C, Macdonald S 2004, with kind permission of Elsevier.) |

The use of forceps

The shape and size of forceps depend on its use. Forceps may be applied in mid-cavity or at the pelvic outlet. They may be used to rotate the fetal head followed by traction in the direction of the curve of Carus to complete the delivery or to apply traction only.

• For traction without rotation, non-rotational forceps such as those designed by Wrigley or Simpson are used for low-cavity delivery, mainly now for delivery of the aftercoming head of the breech. Neville-Barnes or Haig-Ferguson forceps for mid-cavity delivery have a pelvic and cephalic curve although these are now used exclusively for low-cavity non-rotational delivery and the axis traction attachments are rarely used.

• It is important to understand that mid- and high-cavity forceps deliveries (when the fetal head is higher than station +2 cm) are no longer undertaken because of the possibility of trauma. CS is more likely to be the method of choice in those cases.

• To correct malposition from occipitolateral or occipitoposterior to occipitoanterior prior to traction, rotational forceps such as Kielland’s forceps are the design commonly used (RCOG 2005). These forceps have no pelvic curve (straight) so that they can be rotated in the confines of the birth canal. In malpositions there is often asynclitism (tilting of the fetal head). Kielland’s forceps have a sliding lock so that asynclitism can be corrected prior to rotation and traction. There is a gap between the handles when the blades are applied and there is a danger that too much pressure may be applied to the fetal head with the risk of cerebral trauma.

Applying the forceps

Positioning the forceps

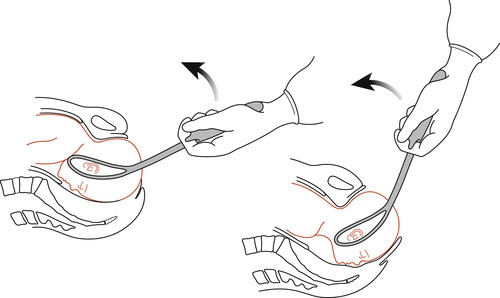

The blades are inserted separately on either side of the fetal head so that they are located alongside the head and over the ears (Fig. 47.2). They should be situated symmetrically between the eye orbits and the ears, reaching from the parietal eminences to the malar area and cheeks (Vacca 1999). They should come together and lock easily without the use of strength if they are applied correctly. Baskett et al (2007) described the line of application extending from the point of the chin to a point on the sagittal suture near the posterior fontanelle.

|

| Figure 47.2 Forceps delivery. (From Henderson C, Macdonald S 2004, with kind permission of Elsevier.) |

The skill of the operator

The operator is a major determinant of the success or failure of instrumental delivery and should have appropriate training prior to conducting operative procedures (RCOG 2005). Unfavourable results are almost always caused by the user’s unfamiliarity with either the instrument or the rules governing its use (Enkin et al 2000). It is important that the skills of using any instrument are acquired under supervision because of the devastating consequences that could arise if mother or baby is damaged during the operation.

Prerequisites for forceps delivery (Chamberlain & Steer 1999)

No obstruction to the descent of the fetus

• The cervix must be fully dilated; attempts to apply forceps blades with an undilated cervix will lead to trauma without successful delivery.

• The membranes should be ruptured.

• The bladder must be empty to prevent trauma.

• No obvious bar should exist such as cephalopelvic disproportion.

• Engagement of the head.

Safeguarding the mother

The RCOG (2005) evaluated a study in the USA, which linked more perineal trauma with vacuum extraction and use of episiotomy compared to forceps delivery. However, they go on to argue that it is not possible to relate these results to UK practice, as within the UK a mediolateral episiotomy is used compared with the midline episiotomy in the USA. The RCOG (2005) acknowledges that the use of episiotomy ‘has crept into clinical practice without formal evaluation’ and advocate for further research to be conducted to explore this issue.

There should be as much safety, comfort and dignity for the woman as possible although the lithotomy position is essential. The procedure is carried out aseptically using sterile instruments.

Safeguarding the baby

• There should be careful and accurate identification of the presentation and position of the fetal head.

• The forceps blades should be applied correctly and their position checked before rotation and/or traction is commenced.

• A paediatrician should be present at the delivery.

• Neonatal resuscitation equipment should be available.

• Some obstetricians prefer manual rotation of the head as it is thought to be less traumatic than instrumental rotation (Hamilton 2003a). Rotational forceps delivery may cause a significant deterioration in fetal acid–base balance (Baker & Johnson 1994).

Complications of forceps delivery

Maternal

• There may be soft tissue damage to the lower uterine segment, cervix, vagina and perineum.

• Bleeding from tissue trauma may lead to postpartum haemorrhage and shock.

• Retention of urine may occur if there is bruising and oedema of the urethra and neck of the bladder.

• Perineal pain may be present once the anaesthesia has worn off.

• Dyspareunia may occur in the long term.

• Psychological effects may lead to avoidance of future pregnancy.

Neonatal

• A cephalhaematoma may form due to friction between the fetal head and the blades or pelvic walls.

• Facial or scalp abrasions are common.

• Bruising of the scalp may lead to neonatal jaundice.

• These problems are more often seen in rotational forceps as is failed forceps delivery resulting in emergency CS (Johanson et al 1992).

Vacuum extraction (ventouse delivery)

Use of the vacuum extractor

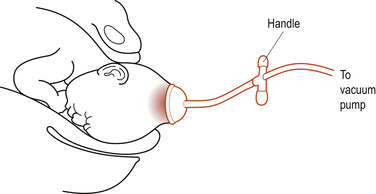

Delivery by the use of vacuum extraction has a history as long as that of forceps delivery and is not new. The modern version was developed by Malmström in the 1950s and has been modified by others (Vacca 1999). Originally, the vacuum extractor consisted of a rounded metal cup in three sizes—40, 50 and 60 mm in diameter (Bird 1969)—and this type of cup is still in use. The cup was attached to a chain and handle and a suction pump to extract air and create a vacuum. The largest cup size that can be passed through the cervix was chosen.

Cups now available are made of silastic, silicone rubber and plastic. Johanson & Menon (2000) compared soft versus rigid vacuum extractor cups. They found that soft cups were significantly more likely to fail to achieve a vaginal delivery than metal cups, although soft cups had better outcomes in a well-flexed vertex. They also found that soft cups were associated with less scalp injury. Metal cups appeared to be more suitable for occipitoposterior, transverse or difficult occipitoanterior position deliveries whereas soft cups seemed to be appropriate for uncomplicated deliveries needing assistance in the second stage. Soft cups deform to follow the contours of the baby’s head during application but the application is poor if there is moderate to severe caput succedaneum. However, Johanson & Menon (2000) advocate more evidence on the use of both soft and metal cups on fetal outcomes. Another form of cup for ventouse delivery is the Kiwi Omnicup. The Omnicup is made of rigid plastic and can be used for malpresentations such as occipitoposterior as well as occipitoanterior positions (Vacca 1999). The Omnicup forms a chignon similar to that formed by metal cups but without the associated scalp injury.

Applying the vacuum extractor

Positioning

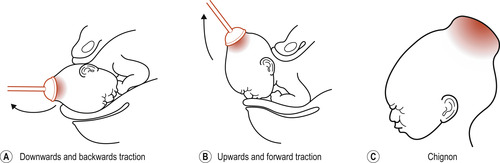

The cup is attached by suction to the fetal scalp as near to the occiput as possible and taking care to avoid the anterior fontanelle (Fig. 47.3). A vacuum is created with a negative pressure of 0.2 kg/cm, drawing an artificial caput (chignon) into the cup (Meakin 2004). The cup is checked for position and to ensure that no maternal soft tissue such as the cervix has been included within the rim. The vacuum pressure is increased to 0.8 kg/cm. This can either be done in stages or in one step. One to two minutes should be allowed for the chignon to develop. There is limited evidence on this issue and currently there is a protocol for a future systematic review on rapid versus stepwise negative pressure application for vacuum extraction assisted vaginal delivery (Suwannachat et al 2007). Traction is then applied following the curve of Carus to enhance the natural forces of uterine contractions and maternal expulsive effort (Figs 47.4A,B).

|

| Figure 47.3 Vacuum extraction. (From Henderson C, Macdonald S 2004, with kind permission of Elsevier.) |

|

| Figure 47.4 Formation of chignon and direction of traction in vacuum extraction. (A) Downwards and backwards traction, (B) Upwards and forward traction, (C) Chignon. |

The skill of the operator

Used skilfully, the advantages of the ventouse are that there is no increase to the presenting diameters and the instrument can be used to flex and rotate the head and to assist the mother to deliver her infant. However, some operators may be too hasty or unskilled and apply traction before suction has been achieved, resulting in the cup coming away from the scalp. Some maternity units have trained midwives to perform ventouse deliveries. The technique is also useful where midwives work alone, without obstetric colleagues, in remote areas of the world. It is important that a midwife is properly trained and is confident in the use of this device and that their employing authority approves the use of ventouse equipment by midwives.

Prerequisites

• These are as for forceps delivery.

• The vacuum extractor is not suitable for application in babies with suspected coagulability.

• It should not be used where contractions are weak or maternal effort is poor.

Complications

Maternal

There is less trauma to maternal tissues than that caused by forceps if the cup has been applied correctly to the fetal head (Johanson & Menon 1999).

There is a tendency for more bleeding due to the abrupt distension of the lower birth canal caused by traction and friction of the fetal head.