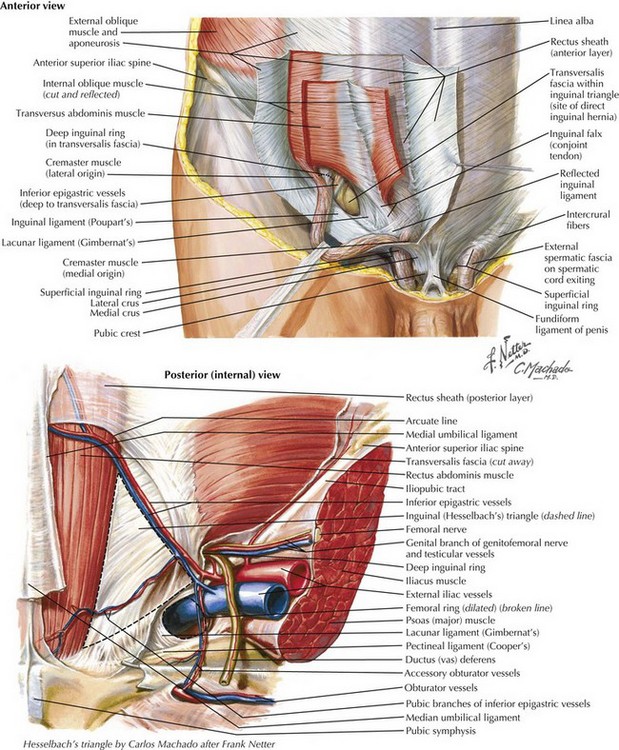

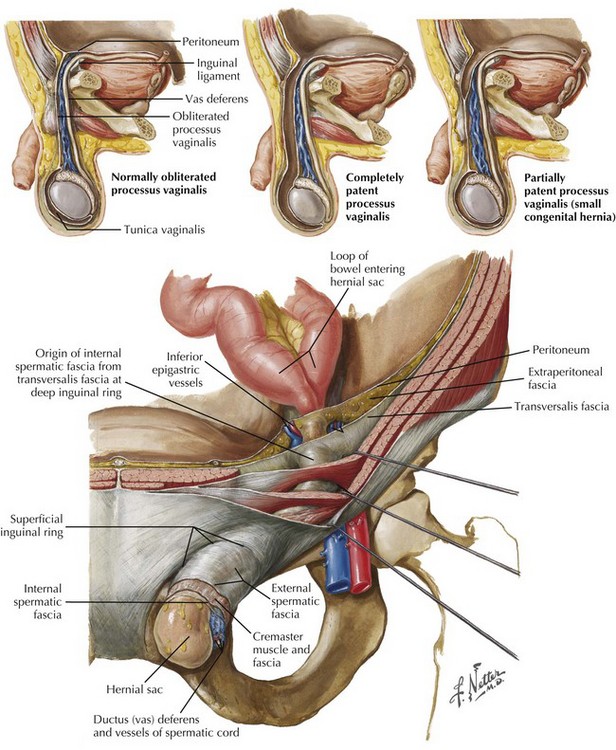

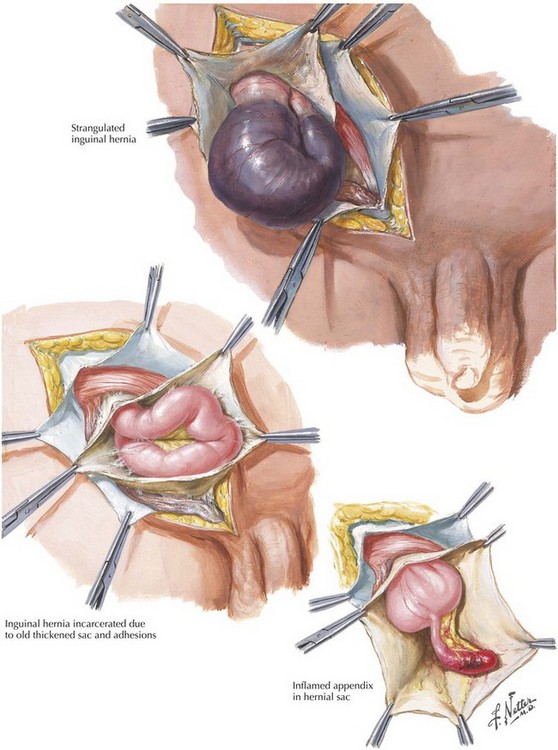

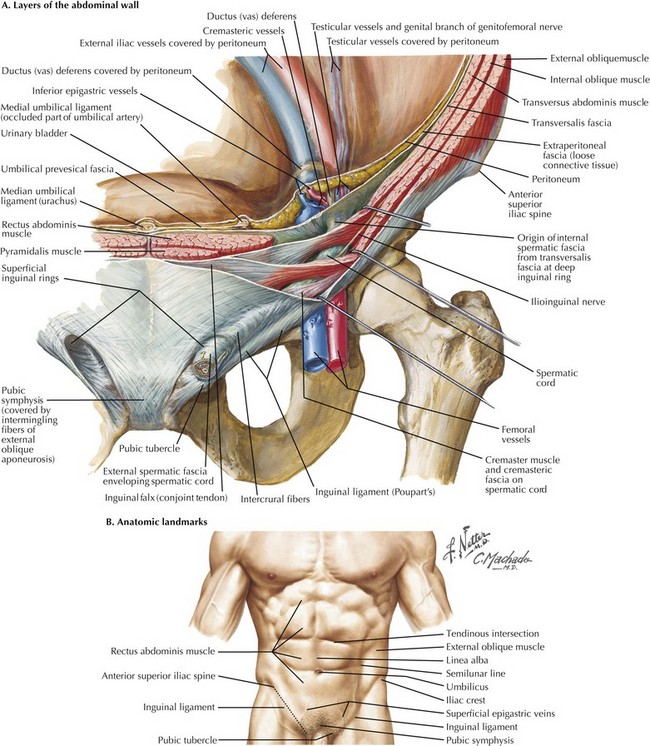

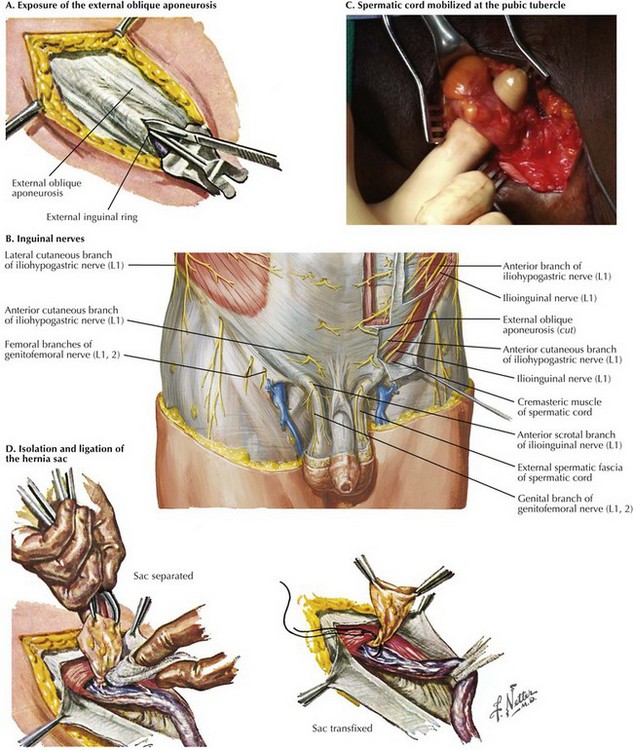

Chapter 28 In referring to inguinal hernias, a major defining point is location of the defect—direct versus indirect. This distinction is strictly anatomic because the operative repair is the same for both types. Approximately two thirds of inguinal hernias are indirect. Men are 25 times more likely to have an inguinal hernia than women, and indirect hernias are more common regardless of gender. A direct inguinal hernia is defined as a weakness in the transversalis fascia within the area bordered by the inguinal ligament inferiorly, the lateral border of the rectus sheath medially, and the epigastric vessels laterally (Fig. 28-1). This area is referred to as Hesselbach’s triangle. Located lateral to the inferior epigastric vessels, an indirect inguinal hernia is characterized by the protrusion of the hernia sac through the internal inguinal ring toward the external inguinal ring and, at times, into the scrotum. Indirect inguinal hernias result from a failure of the processus vaginalis to close completely (Fig. 28-2). An inguinal hernia that has direct and indirect components is referred to as a pantaloon hernia. A hernia is defined as reducible if its contents can be placed back into the peritoneal cavity, alleviating their displacement through the musculature. In contrast, a hernia with contents that cannot be reduced is termed incarcerated (Fig. 28-3). If the blood supply to the contents of the hernia is compromised, the hernia is defined as strangulated. Strangulation is a potentially fatal complication of a hernia and should always be considered a surgical emergency. Less common inguinal hernias include Amyand’s hernia, with the appendix (normal or acutely inflamed) contained in the hernia sac, and Littre’s hernia, which contains a Meckel’s diverticulum. To understand the anterior approach, the surgeon must appreciate the layers of the abdominal wall and their relation to the inguinal canal. The layers and the location of their neurovascular structures include skin, subcutaneous fat (e.g., Camper’s and Scarpa’s fasciae), muscles (external and internal oblique, transversus abdominis), transversalis fascia, preperitoneal fat, and peritoneum (Fig. 28-4, A). The inguinal canal is approximately 4 cm in length and extends from the internal inguinal ring to the external inguinal ring. Within the inguinal canal lies the spermatic cord, which consists of the testicular artery, pampiniform venous plexus, the genital branch of the genitofemoral nerve, the vas deferens, cremasteric muscle fibers, cremasteric vessels, and the lymphatics. The superficial border of the inguinal canal is the external oblique aponeurosis. As the external oblique aponeurosis forms the inguinal (Poupart’s) ligament, it rolls posteriorly, forming a “shelving edge,” and defines the inferior border of the inguinal canal with the lacunar ligament. Posteriorly, the inguinal canal is bound by the transversalis fascia, often referred to as the “floor” of the inguinal canal. The inguinal canal is bound superiorly by the internal oblique and transversus abdominis musculoaponeurosis (see Fig. 28-1). Before making an incision, it is essential for the surgeon to identify the landmarks defining the inguinal ligament. The anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) and pubic tubercle are the insertion points for the inguinal ligament (Fig. 28-4, B). One of the challenging aspects of open inguinal hernia repair is securing the mesh to medial components. To help expose this area, the incision should begin over the pubis and extend 1 to 2 cm cephalad to the inguinal ligament, from the external ring to the internal ring. Dissection through the subcutaneous fat and Scarpa’s fascia leads to the external oblique aponeurosis. Once encountered, the external oblique aponeurosis is completely exposed and the external inguinal ring is identified. The external oblique aponeurosis is incised sharply. The incision is extended along the fibers of the external oblique aponeurosis to the external inguinal ring, to expose the inguinal canal (Fig. 28-5, A).

Open Inguinal Hernia Repair

Terminology

Surgical Approach

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Basicmedical Key

Fastest Basicmedical Insight Engine