Chapter 6 Nose and Mouth

A. The Nose

(2) The External Nose

8 What is lupus pernio?

It is a chronic, nonblanching, diffuse, and purple skin discoloration of the external nose, in the absence of true nasal enlargement (Fig. 6-2). Hence, it differs from rhinophyma. A sign of active sarcoid, it may occur with uveitis, erythema nodosum, and pulmonary involvement. It may also coexist with lesions of the ears, cheeks, hands, and fingers. The term lupus refers to any disfiguring skin condition that, like a wolf (lupus in Latin) “devours” the patient’s facial features. It is thus used with modifying terms to designate various disfiguring skin diseases, such as lupus verrucosus, lupus erythematosus, lupus tuberculosis, lupus vulgaris, and, of course, lupus pernio. Pernio is Latin for frostbite and refers to the peculiar violet-bluish hue of the condition (see Chapter 3, The Skin, question 265).

(3) The Internal Nose

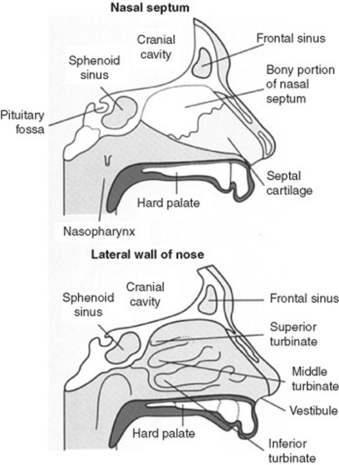

10 What are the normal structures of the internal nose?

The normal internal structures are shown in Fig. 6-3:

1. The vestibules. As indicated by the term, these are paired internal widenings, immediately beyond each naris. They are delimited:

Medially by the septum. Like the external nose, this is partly bony and partly cartilaginous. The word septum is an anglicized adaptation of the Latin saepire, “to erect a hedgerow.” Indeed, the function of the septum is to provide a medial boundary to each vestibule.

Medially by the septum. Like the external nose, this is partly bony and partly cartilaginous. The word septum is an anglicized adaptation of the Latin saepire, “to erect a hedgerow.” Indeed, the function of the septum is to provide a medial boundary to each vestibule.2. Deeply beyond the vestibules are the turbinates, or conchae. These are curving bony structures that project into the internal nose. There are three turbinates (and three corresponding meatuses) in each nasal cavity: superior, middle, and inferior. Their main function is to increase the nasal surface for humidification, temperature control, and filtering of inhaled air. To do so, they are covered by a well-vascularized and erectile mucosa.

Figure 6-3 The internal nose.

(From Epstein O, Perkin CD, de Buono DP, Cookson J: Clinical Examination, 2nd ed. St. Louis, Mosby, 1998.)

13 What is the significance of flaring of the nostrils?

Flaring of the nostrils (i.e., of the alae of the nose) is a sign of increased work of breathing, typical of impending respiratory failure. It is often associated with other findings of distress, such as respiratory alternans and abdominal paradox (see Chapter 13, Chest Inspection, Palpation, and Percussion, questions 52–58). It also can occur in peritonitis as a result of impaired and painful excursion of the diaphragm.

14 What are the best tools for inspecting nares and internal nose?

Otoscope: This can be mounted with a nasal speculum (instead of an ear speculum) and thus used to shine a light directly into each vestibule.

Otoscope: This can be mounted with a nasal speculum (instead of an ear speculum) and thus used to shine a light directly into each vestibule.

Handheld Vienna nasal speculum: This is a speculum that opens upon closure of the handles. It is commonly used with a head mirror (Fig. 6-4).

Handheld Vienna nasal speculum: This is a speculum that opens upon closure of the handles. It is commonly used with a head mirror (Fig. 6-4).

15 Is inspection of nasal secretions useful?

A clear discharge is suggestive of viral or atopic rhinitis.

A clear discharge is suggestive of viral or atopic rhinitis.

A yellow discharge may instead indicate an early suppurative process.

A yellow discharge may instead indicate an early suppurative process.

A green discharge is quite consistent with purulent sinusitis.

A green discharge is quite consistent with purulent sinusitis.

Obviously, a bloody discharge suggests anterior epistaxis.

Obviously, a bloody discharge suggests anterior epistaxis.

A dark and almost black discharge (especially in comatose diabetics) argues for mucormycosis.

A dark and almost black discharge (especially in comatose diabetics) argues for mucormycosis.

17 What are the causes of swelling/bumps in the nasal septum?

All require ENT referral, since an untreated hematoma (or abscess) may result in septal perforation.

23 What are the common causes of a septal perforation?

Traumatic: Facial injury or self-induced lesions (nose picking/piercing)

Traumatic: Facial injury or self-induced lesions (nose picking/piercing)

Iatrogenic: Prior septal surgery, nasogastric tube placement, or nasal intubation

Iatrogenic: Prior septal surgery, nasogastric tube placement, or nasal intubation

Inflammatory/malignant: Often the sequela of untreated septal hematomas or abscesses

Inflammatory/malignant: Often the sequela of untreated septal hematomas or abscesses

Cocaine snorting: One of the most frequent causes today, often presenting with large and expanding perforations. Cocaine contains adulterants that may irritate the mucosa, plus has strong alpha-agonist effects (causing vasoconstriction and ischemia of the nasal cartilage). Nasal obstruction often accompanies perforation.

Cocaine snorting: One of the most frequent causes today, often presenting with large and expanding perforations. Cocaine contains adulterants that may irritate the mucosa, plus has strong alpha-agonist effects (causing vasoconstriction and ischemia of the nasal cartilage). Nasal obstruction often accompanies perforation.

24 What are the less-common causes of perforation?

Chemical irritants (chromic or sulfuric acid fumes, glass dust, mercurials, and phosphorous)

Chemical irritants (chromic or sulfuric acid fumes, glass dust, mercurials, and phosphorous)

Infections (tuberculosis, syphilis, and, more rarely, leprosy)

Infections (tuberculosis, syphilis, and, more rarely, leprosy)

Collagen vascular diseases (Wegener’s, midline granuloma, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, mixed connective tissue disease, and progressive system sclerosis)

Collagen vascular diseases (Wegener’s, midline granuloma, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, mixed connective tissue disease, and progressive system sclerosis)

28 What results in swelling of the nasal mucosa?

Viral: Nasal and oropharyngeal infections by either rhinoviruses or adenoviruses

Viral: Nasal and oropharyngeal infections by either rhinoviruses or adenoviruses

Atopic: Pollen or dander exposure causing nasal congestion, allergic (serous) conjunctivitis, and sneezing

Atopic: Pollen or dander exposure causing nasal congestion, allergic (serous) conjunctivitis, and sneezing

Vasomotor: Response to a specific inhalant, characterized by boggy edema of the mucosa and marked tearing. Inhalants may either be noxious to all (such as tear gas) or only to some. For example, perfumes may elicit an idiosyncratic response in a few predisposed individuals, causing pronounced swelling of the nasal mucosa.

Vasomotor: Response to a specific inhalant, characterized by boggy edema of the mucosa and marked tearing. Inhalants may either be noxious to all (such as tear gas) or only to some. For example, perfumes may elicit an idiosyncratic response in a few predisposed individuals, causing pronounced swelling of the nasal mucosa.

33 What is anosmia?

It is the congenital or acquired absence of smell (from the Greek an, lack of, and osme, smell).

Acquired anosmia may result from a long list of disease processes, affecting either the central nervous system or nose. Among them are multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, diabetes mellitus, pernicious anemia, liver cirrhosis, chronic renal insufficiency, Cushing’s syndrome, cystic fibrosis, sarcoidosis, allergic rhinitis, nasal polyposis, and zinc deficiency. Still, sequelae of a viral infection are often the most common reasons for acquired reversible anosmia.

Acquired anosmia may result from a long list of disease processes, affecting either the central nervous system or nose. Among them are multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, diabetes mellitus, pernicious anemia, liver cirrhosis, chronic renal insufficiency, Cushing’s syndrome, cystic fibrosis, sarcoidosis, allergic rhinitis, nasal polyposis, and zinc deficiency. Still, sequelae of a viral infection are often the most common reasons for acquired reversible anosmia.

Congenital anosmia is almost always caused by Kallmann’s syndrome. Described by the German psychiatrist Franz J. Kallmann (1897–1965), this consists of familial hypogonadotropic hypogonadism with or without anosmia (usually characterized by congenital absence of olfactory lobes). Kallmann’s is inherited through sex-linked recessive or autosomal transmission, with expression mostly in males. It can be treated with gonadotropins.

Congenital anosmia is almost always caused by Kallmann’s syndrome. Described by the German psychiatrist Franz J. Kallmann (1897–1965), this consists of familial hypogonadotropic hypogonadism with or without anosmia (usually characterized by congenital absence of olfactory lobes). Kallmann’s is inherited through sex-linked recessive or autosomal transmission, with expression mostly in males. It can be treated with gonadotropins.

B. The Oral Cavity

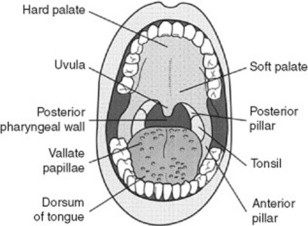

(2) Posterior Pharynx and Tonsils

37 What is a cleft palate?

A congenital deformity that is usually corrected in infancy but may persist into adulthood. It is quite common (1 case in 1000 live births, with or without cleft lip), with greater prevalence in Native Americans (3.6 cases per 1000 live births), and lower in African Americans (0.3 cases per 1000 live births). Of all cases, 20% are an isolated cleft lip; 50% are a cleft lip and palate, and 30% are a cleft palate alone. Cleft lip and palate together are more common in males, whereas isolated cleft palate is more common in females. Bifid uvula occurs in 1 of 80 patients, often in isolation (see question 38).

38 What is the uvula? What disease processes may affect it?

Absent uvula: Usually due to surgical removal as part of uvulopalatopharyngoplasty (UPPP) for obstructive sleep apnea. May result in inhalation of swallowed fluids.

Absent uvula: Usually due to surgical removal as part of uvulopalatopharyngoplasty (UPPP) for obstructive sleep apnea. May result in inhalation of swallowed fluids.

Bifid uvula: Fascinating but entirely benign normal variant, wherein the uvula is congenitally forked. Not a sign of lying, it may instead be associated with an occult cleft palate. Look for it.

Bifid uvula: Fascinating but entirely benign normal variant, wherein the uvula is congenitally forked. Not a sign of lying, it may instead be associated with an occult cleft palate. Look for it.

Bobbing uvula: Patients with chronic and severe aortic insufficiency may have a rhythmic pulsatile movement of the uvula (Mueller’s sign). This is the equivalent of the de Musset sign (see Chapter 1, Facies, General Appearance, and Body Habitus, questions 51 and 54) and is quite rare nowadays, thanks to timely valvular treatment.

Bobbing uvula: Patients with chronic and severe aortic insufficiency may have a rhythmic pulsatile movement of the uvula (Mueller’s sign). This is the equivalent of the de Musset sign (see Chapter 1, Facies, General Appearance, and Body Habitus, questions 51 and 54) and is quite rare nowadays, thanks to timely valvular treatment.

Neoplastic uvula (squamous cell degeneration): As for many other oropharyngeal structures.

Neoplastic uvula (squamous cell degeneration): As for many other oropharyngeal structures.

41 What are the causes of a diffuse reddening of the oropharynx?

The most common are viral and bacterial infections:

43 What are the causes of an exudate (i.e., pus) on the posterior pharynx?

Many agents can cause exudative pharyngitis (Table 6-1), the most important being upper respiratory tract viruses, group A beta-hemolytic streptococci, and the EBV.

Table 6-1 Causes of exudative posterior pharyngitis

| Pathogen | Probability (%) |

|---|---|

| Viral | 50–80 |

| Streptococcal | 5–36 |

| Epstein-Barr virus | 1–10 |

| Chlamydia pneumoniae | 2–5 |

| Mycoplasma pneumoniae | 2–5 |

| Neisseria gonorrhoeae | 1–2 |

| Haemophilus influenzae type b | 1–2 |

| Candidiasis | <1 |

| Diphtheria | <1 |

(Data from Ebell M, et al: Does this patient have strep throat? JAMA 284:2912–2918, 2000.)

44 What are the clinical features of viral upper respiratory tract infections?

Pharyngeal vesicles and ulcers. These are so typical as to argue against group A streptococci being the cause of the patient’s sore throat (see herpangina, questions 87 and 89).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree