34

CHAPTER OUTLINE

■ NONMEDICAL USE AMONG ADOLESCENTS AND YOUNG ADULTS

■ SOURCES OF PRESCRIPTION MEDICATIONS

■ DRUG POISONING DEATHS AND LEGAL CONSEQUENCES

■ PREVENTION OF PRESCRIPTION DRUG ABUSE

■ PRESCRIPTION MONITORING PROGRAMS

■ MANAGEMENT OF PRESCRIPTION DRUG ABUSE

■ SUMMARY

Abuse of illicit drugs such as marijuana, heroin, and cocaine has been a concern since the latter half of the 20th century, but, in the first decade of the new millennium, there are additional problems caused by the rapid growth of prescription drug abuse, particularly high-potency opioids (1,2). The abuse of controlled medications is complex because it involves the physician prescribing as well as the patient gaining access to powerful drugs with high abuse risks and resale value (3). Controlled medications, such as those prescribed to relieve pain, anxiety, depression, insomnia, narcolepsy, and attention deficit disorders, are increasingly misused, abused, diverted, implicated in addiction, and linked to nonfatal overdose and deaths. The scheduled (controlled) drug classes most often involved in nonmedical use are opioid analgesic, sedative–hypnotic, sedative–anxiolytic, and stimulant medications.

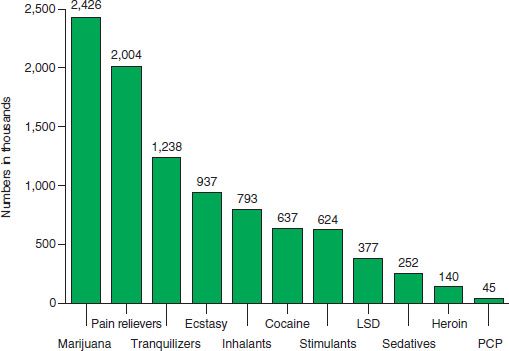

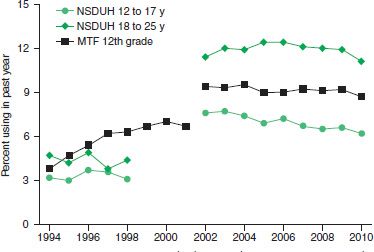

Prescription opioid medications are second only to marijuana as the most common first illicit drug used among individuals over 12 years of age (Fig. 34-1) (4). A 10-year trend toward greater nonmedical use among adolescents and young adults is now apparent (5–7). The National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) and Monitoring the Future study find significant increases in nonmedical use of prescription opioids in particular (8) (Fig. 34-2). Although the motives for nonmedical use vary among young people—including self-treatment as well as sensation seeking—any nonmedical use places an adolescent at risk for injury, addiction, and overdose death (9,10).

FIGURE 34-1 Past-year initiates of specific illicit drugs among persons aged 12 or older: 2010. (From Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2010 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings, NSDUH Series H-41, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 11–4658. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2011.)

FIGURE 34-2 Past-year nonmedical pain reliever use among youths and young adults in the NSDUH and MTF: 1994 to 2010. (From Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, et al. Marijuana use continues to rise among U.S. teens, while alcohol use hits historic lows. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan News Service, 2011. Retrieved February 18, 2013 from http://www.monitoringthefuture.org)

Although adolescents and young adults have the highest prevalence rates for nonmedical use, adult patients misusing or diverting medications is also a problem. Indeed, it is often hard to differentiate between those patients addicted to pain medication and those seeking analgesic relief in primary care offices (11,12) and pain clinics (13,14). Even the most scrupulous and appropriate prescriber knows that once a prescription is written, patient behavior (or family behavior) can lead to diversion for nonmedical use.

This chapter presents an overview of what is known about nonmedical use, misuse, and abuse of prescription medications. The chapter also reviews sequelae from nonfatal poisonings, in which ingestion of a prescription medication causes serious harm, to the most serious consequence, overdose death. Strategies for the identification and management of the patient engaged in the nonmedical use of prescription medications will be presented as well as selected prevention strategies.

Various scientific, clinical, and research definitions of misuse, abuse, addiction, problematic use, and nonmedical use of prescription medications exist. This leads to difficulties in estimating the incidence and prevalence of the problem (1). Compton and Volkow focus upon individuals without prescriptions by defining nonmedical use as “any intentional use of a medication with intoxicating properties outside of a physician’s prescription for a bona fide medical condition, excluding accidental misuse.” According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse, a patient with a prescription for a psychoactive medication taking the medication in ways other than those intended by the prescriber, increasing the dose without a physician’s knowledge, or combining medications without the prescriber’s awareness is engaging in medication misuse (1). The term prescription drug abuse is generally used as an “umbrella term” and includes both nonmedical use and medical misuse.

Boyd and McCabe expand on Compton and Volkow’s definition in their extensive research on this subject (4,5,8,15–20). First, they distinguish between medical and nonmedical users (16) and then note that people with a legitimate prescription may use the medication to self-treat (e.g., take more than prescribed) or to sensation seek (e.g., take to get high) (4). These people are termed medical misusers since they are using their own prescriptions. They may also take more than prescribed (altering the prescribed dose, not taking the medication within a prescribed time interval) or coingest medication with alcohol or other psychoactive drugs (16). Alternatively, people may use someone else’s medication (4). These people are the nonmedical users of prescription medications. Self-treatment motivations carry different risks than sensation-seeking motivations, although all medical misuse and nonmedical use place the user at risk for accidental events and substance use disorders (5,6).

Public perception that prescription drug abuse differs from “street drug use” was described by a national survey 20 years ago in the 1992 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse, the precursor to NSDUH. Of those respondents who denied engaging in nonmedical use of prescription medications, 70% admitted to taking their medications more often, taking in greater amounts than prescribed, or taking medication that was borrowed or bought without a prescription (15). Few endorsed taking a drug for kicks, to get “high,” to feel good, or out of curiosity. These findings suggest that there is a cultural belief that abuse of prescription drug only includes behavior focused on seeking euphoria or an altered state. Self-treatment with someone else’s medication was not seen as a problem. These results underline the importance of educating patients about appropriate use of medications. From the point of view of the patient, education about unintended risks of excessive doses or combinations of medications is most important.

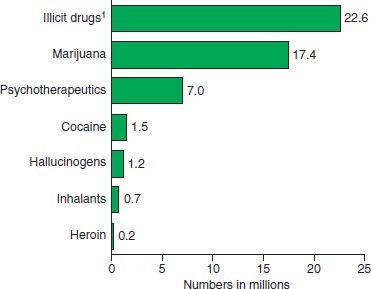

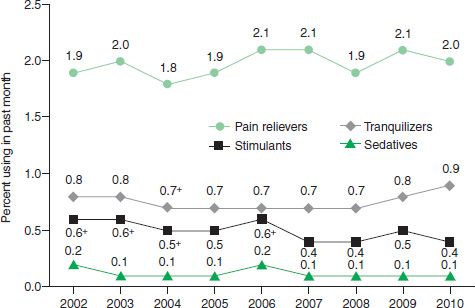

Several epidemiologic studies and national population surveys have reported an increase in nonmedical use of prescription medications that began in the 1990s. The annual NSDUH uses a computer-assisted survey method to ask respondents, “Have you ever, even once, used [insert the name of a specific medication] that was not prescribed for you or that you took only for the experience or feeling it caused?” The NSDUH uses pill cards with pictures to assist the respondent in identification of particular medications. Between 2006 and 2010, the percentage of Americans aged 12 or older reporting nonmedical use of psychotherapeutic medications in the prior month has been stable. In the 2010 survey, 7 million people (2.7% of the population surveyed) reported nonmedical use (Fig. 34-3). The NSDUH defines psychotherapeutic medications to include any prescription-type pain relievers, tranquilizers, stimulants, or sedatives. Prescription opioid medications are the type of medication most often used in a nonmedical manner, a consistent pattern since 2002 (Fig. 34-4). These results should be interpreted with caution since, as noted above, individuals with very different conditions and motivations for use may answer the questions in the affirmative.

FIGURE 34-3 Past-month illicit drug use among persons aged 12 or older: 2010. (From Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2010 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings, NSDUH Series H-41, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 11–4658. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2011.)

FIGURE 34-4 Past-month nonmedical use of types of psychotherapeutic drugs among persons aged 12 or older: 2002 to 2010. +Difference between this estimate and the 2010 estimate is statistically significant at the 0.05 level. (From Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2010 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings, NSDUH Series H-41, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 11–4658. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2011.)

The increase in nonmedical use of prescription medications among young women adversely affects the entire family, particularly neonates and young children. Among the population of pregnant women, it is difficult to estimate the prevalence of illicit substance use due to the added stigma of perinatal addiction, prevalence of multiple substances used, legitimate prescription of psychiatric medications for dual diagnoses, abuse of tobacco, and potential consequences of loss of child custody when abuse and/or addiction is discovered. However, proxy measures such as the increase in the diagnoses of antepartum opiate use and neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) between 2000 and 2009 in the United States suggest that substance use disorders are identified more often among pregnant and parenting women (16). An analysis of health care expenditures revealed a more than threefold increase in the incidence of NAS from 1.20/1,000 births (95% CI, 1.04 to 1.37) in 2000 to 3.39/1,000 live births (95% CI, 3.12 to 3.67) in 2009. There has been more than a fourfold increase in antepartum maternal opioid use with an increase of 1.9/1,000 affected hospital births per year (95% CI, 1.01 to 1.35) in 2000 to 5.63/1000 affected births in 2009 (95% CI, 4.40 to 6.71). Both increases are statistically significant (p < 0.0001) and are indicative of the great burden perinatal addiction places upon the health care system. For more information about the effect of non-medical use of prescription medications on pregnancy and newborns, please see Chapter 81.

Unintentional child poisonings with opioids (buprenorphine, fentanyl, hydrocodone, hydromorphone, methadone, morphine, and oxycodone) have increased among children under age 6. Between January 2003 and June 2006, the Researched Abuse, Diversion and Addiction-Related Surveillance (RADARS) System reported that 9,179 children (54% male, median age 2 years) were exposed to a prescription opioid. This resulted in eight deaths and many more seriously ill children. Exposures were primarily ingestions of a medication prescribed to an adult in the household. RADARS reported that pediatric exposures were more likely to occur in communities where more prescriptions had been filled for opioids (21).

In another study to elucidate the prevalence of the problem of prescription opioid abuse, RADARS pooled information from drug abuse experts, law enforcement, and poison control centers. They reported an increase in abuse of all prescription opioids in the United States; extended-release and immediate-release oxycodone and hydrocodone were the most widely abused medications (22,23). According to their reports, those abusing prescription opioids were more likely to live in rural, suburban, and small-to medium-sized urban areas, although these demographic factors may be changing. Now much expanded in scope and located at the Rocky Mountain Poison and Drug Center-Denver Health, RADARS continues to be a rich source of data about nonmedical use of prescription medications.

Prescription Opioids and Chronic Pain

The reported prevalence of nonmedical use of opioid prescription medication among patients with prescriptions, predominantly prescribed for chronic pain, varies significantly due to lack of agreement in the definition of misuse, abuse, addiction, or problematic behavior; variations in identification and screening; and the criteria used to define opioid abuse or addiction (24,25). Study populations can include patients with cancer, patients with nonmalignant chronic pain, patients in treatment for addiction, or those treated for pain in primary care settings. In some studies, patients with known addiction are excluded. The American Society of Interventional Pain Physicians provides important guidelines for the clinician interfacing with this population (26,27).

Benzodiazepine Medications

A review of benzodiazepine treatment in the last 50 years reveals that prescribers are well aware of potential for abuse and addiction to these sedative–anxiolytics (28). In the last decade, the increase in the nonmedical use of benzodiazepines, most commonly alprazolam, clonazepam, and diazepam, has been widely reported. The NSDUH, which classifies benzodiazepines as tranquilizers, reports that in the prior 30 days about 1% of those using illicit drugs also endorse abusing benzodiazepines (see Fig. 34-3), a steady trend since 2002. The Treatment Episode Data Set reported that treatment for benzodiazepines, as a primary problem, increased from 2.5% of admissions in 1992 to nearly 20% in 2009 (29). Some patients in opioid addiction treatment such as methadone maintenance or office-based buprenorphine treatment continue to abuse benzodiazepines (30).

Between 1999 and 2008, poisonings involving benzodiazepines increased along with opioid analgesic overdose deaths (31), and benzodiazepines have increasingly been involved in opioid overdose deaths where methadone was identified (32–34). In an analysis of overdose deaths in France, where methadone and/or buprenorphine was implicated, benzodiazepines were postulated to have been a synergistic factor along with alcohol and other neuroleptics (35). It has been known since the 1990s that those using benzodiazepines nonmedically were more likely to have anxiety symptoms and serious mental illness, to engage in illicit drug use, to initiate drug use at a younger age, and to use drugs intravenously (36). Epidemiologic information, as well as clinical experience, informs physicians that individuals use sedative hypnotics and tranquilizers for a variety of reasons. These patients are at higher risk for other forms of substance abuse as well. In any case, it is important to note that benzodiazepines are no longer considered firstline chronic medications for the treatment of anxiety and panic disorder; that role has been assumed by selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.

NONMEDICAL USE AMONG ADOLESCENTS AND YOUNG ADULTS

Earlier onset of alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana use is associated with development of increased rates of substance dependence in adulthood (37). A similar picture is emerging for early nonmedical use of prescription medications. In the 2001–2002 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions, researchers found that if respondents reported using a scheduled prescription medication nonmedically before age 13, they were significantly more likely to have a diagnosis of prescription medication abuse or dependence than individuals who began nonmedical use at 21 years (or older) (17). Additionally, individuals who had reported beginning nonmedical of prescription medication use at younger age (18 to 24) at Wave 1 had higher odds (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 3.42) of meeting criteria for opioid or other abuse/dependence at Wave 2 than those individuals who began use after age 24 (15). Moreover, in a school-based sample of adolescents, nonmedical use of prescription medication was also associated with other drug use, including alcohol, tobacco, marijuana, and other illicit drugs, as well as reports of substance use problems (18). Among adolescents, nonmedical prescription opioid use may escalate from oral to nasal to IV administration and, perhaps because of the cost of prescription medications, may progress to less-costly heroin abuse and addiction (38).

Prevalence

Nearly 6% of young adults report nonmedical use of a scheduled pain medication in the past month (4). Less is known about pharmaceutical stimulant misuse and abuse than about prescription opioids; however, nonmedical use of stimulants appears to be most prevalent after high school among young adults aged 18 to 25 (39,40). Although self-medication (dextroamphetamine, methylphenidate) often involves use of a single drug to increase attention or improve concentration for study or to reduce hyperactivity, nonmedical use often occurs in conjunction with alcohol and other substances (with males more likely than females to engage in instances of polydrug use) (41,42). In cases of intoxication or overdose, the physician should suspect involvement of more than one substance. Urine toxicology results can be helpful in the management of the patient.

Motivation for Adolescent/Young Adult Misuse

Adolescents and young adults engaging in nonmedical use frequently endorse self-treatment as a reason for use. In one Web-based survey of Midwestern 10- to 18-year-olds, adolescents were asked to endorse reasons for nonmedical use and most often endorsed treatment of symptoms for which a medication is often prescribed, including using stimulants to study, focus, and lose weight; pain medication to relieve pain; and tranquilizers and sedative hypnotics for anxiety or as sleep aids (19,43). However, some respondents candidly endorsed experimentation, “to get high,” and “because I’m addicted,” as reasons for use. As with the general population, the motivation for nonmedi-cal use in youth can range from “self-treatment,” to experimentation, intoxication or euphoria. Those who endorsed reasons other than self-treatment for nonmedical use were significantly more likely to have substance abuse problems as indicated by high scores on the Drug Abuse Screening Test-10 (44). When working with teens and young adults, physicians should be aware of the use of alcohol and other drugs in addition to prescription medications, consider multiple motivations including self-treatment, and have a high index of concern for the potential for accidental overdose.

SOURCES OF PRESCRIPTION MEDICATIONS

Most controlled medications used nonmedically are obtained from friends and family, although other sources include prescriptions from one physician, multiple physician offices, emergency departments, and/or urgent care sites; theft in the distribution chain including from pharmacies; online purchases; stealing from friends or family members who have them legally prescribed; forging prescriptions; and purchase from strangers or “drug dealers” (19,45).

Information obtained from prescription opioid abusers, both in treatment and still actively using, sheds some light on the provenance of medications diverted to nonmedical use and abuse. Sources (from most often to least often) are drug dealers, sharing/trading, legitimate medical practices, illegitimate medical practices (“pill mills”), and theft (46). Drug dealers participating in qualitative interviews reported strategies to procure medication. These included posing as patients visiting multiple pain clinics, stealing from pharmacies with the cooperation of employees, and purchase of medication prescribed to indigent patients. The most commonly sold medications were prescription opioid analgesics followed by benzodiazepines such as alprazolam (47). Although this study was conducted in heavily affected south Florida, the findings may generalize to other communities.

The NSDUH 2010 data indicate that, among respondents age 12 or older who used pain relievers nonmedically in the past 12 months, the most common source of opioid medications was “from a friend or relative for free” (55%) and 79% of the time the friend or relative was prescribed the drugs from just one doctor. Only 17.3% of respondents had themselves obtained medication from a doctor, another 11.4% bought them from a friend or relative (increased from 8.9% in 2007 to 2008), 4.8% took them from a friend or relative without asking, and less than 1% bought medication on the Internet (4). Purchase from street sources was less common, with only 4.4% buying pain relievers from a drug dealer or other strangers. Where known, stimulant medications appear to be more often (than is observed for prescription opioids) obtained from a drug dealer or other strangers (6.5%) and through the Internet (7.2%). Although most surveys report relatively little use of the Internet as a source for nonmedical use, there is a proliferation of online storefronts that sell and ship primarily Schedule III and IV medications, often without the need for a prescription (48–50). The sources of benzodiazepines are not well described in the literature; however, it is likely that they are commonly obtained, as other prescription medications, from friends and family.

Adolescents may take bottles of medications from their parents’ medicine cabinets, with or without their knowledge, or misuse or divert their own prescribed medications to peers. Students in middle and high school are more likely to get medication from family or peers (51), male college students are more likely to obtain diverted medications from peers, and family members remain the source of sedative– hypnotic, sleeping, and pain medications for women (20). In the case of nonmedical use of stimulants, high school and college students are often approached at school to share or sell their own legitimately prescribed medications (41).

The number of opioids prescribed to adolescents and young adults (ages 15 to 29) nearly doubled between 1994 and 2007 (52). Although a causal relationship has yet to be elucidated, increased rates of prescribing may have provided access to medications diverted for nonmedical use and abuse. More than half of these opioid prescriptions were for hydrocodone- and oxycodone-containing products. For patients aged 10 to 19, dentists were the main prescribers, followed by non–pediatrician primary care, and emergency medicine physicians; the same three groups were the predominant prescribers for the 20 to 29 age group, although with predominance shifted from dentists toward non–pediatrician primary care physicians (53).

Screening for substance use problems among teens may decrease nonmedical use. The CRAFFT is a validated screening measure for alcohol and drug abuse among teens that also successfully screens for the risk of nonmedical use in this age group (54,55).

DRUG POISONING DEATHS AND LEGAL CONSEQUENCES

In 2007, approximately 27,000 unintentional drug overdose deaths occurred in the United States, one death every 19 minutes (56).

The most devastating consequence of prescription drug abuse is progression to unintentional overdose leading to a fatality. A review of the pathophysiology and guidelines regarding clinical management of opioid overdose is beyond the scope of this review and has been covered elsewhere (57).

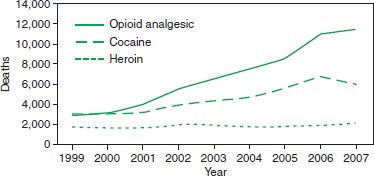

While illicit opioid heroin poisonings increased by 12.4% from 1999 to 2002, the number of prescription opioid analgesic poisonings in the United States increased by 91.2% during that same time period (58). Thus, prescribed drugs have supplanted the illicit drugs heroin and cocaine as the leading cause of drug-related overdose deaths (59) (Fig. 34-5). The stigma of drug abuse and addiction, a lack of timely or accurate death certificate data, an absence of standards for investigation of drug deaths, inadequate toxicologic testing, and differences in death classification by medical examiners may contribute to postulations of under-reporting and underestimation of decedent cases.

FIGURE 34-5 Unintentional drug overdose deaths involving opioid analgesics, cocaine, and heroin in the United States during 1999 to 2007. (From National Vital Statistics System. Multiple cause of death dataset. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss.html)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree