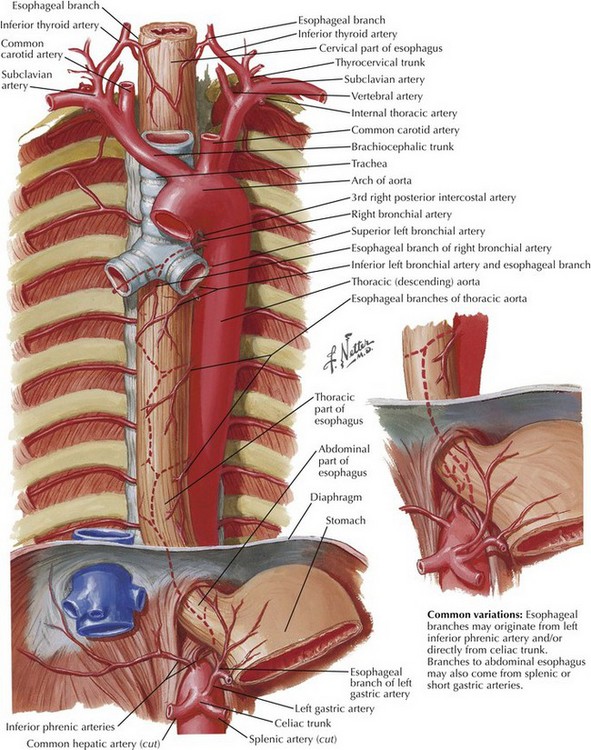

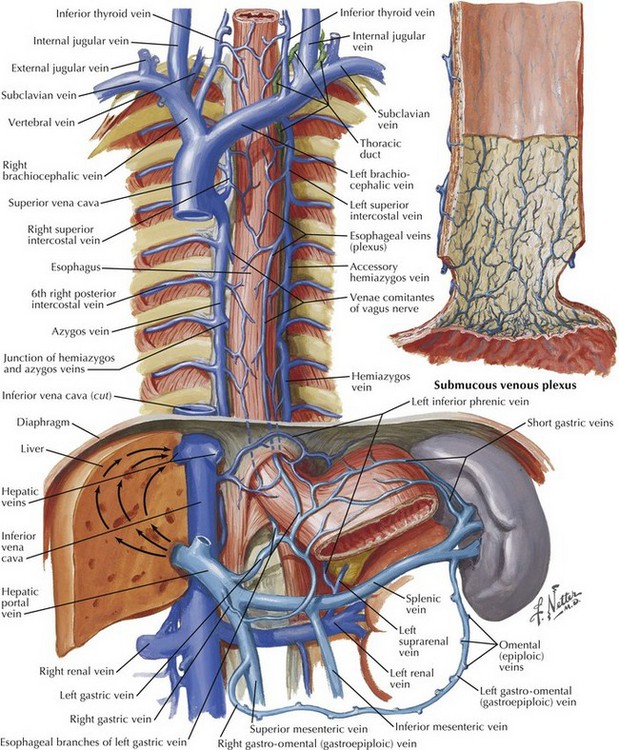

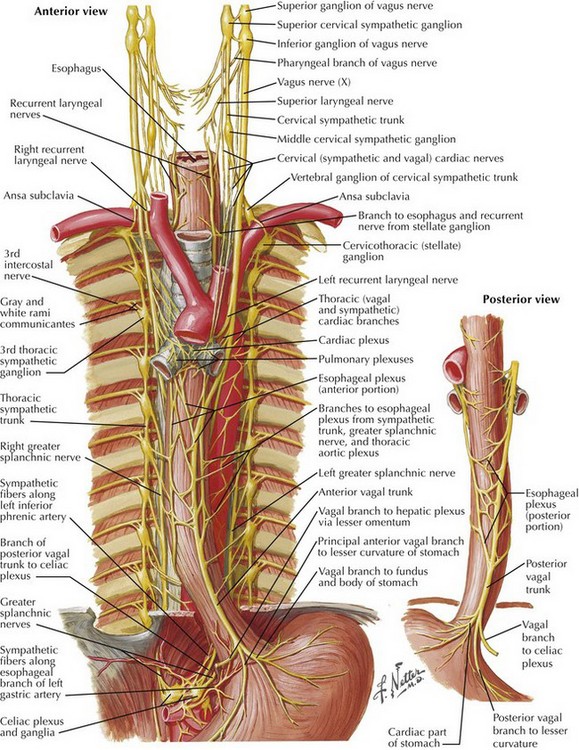

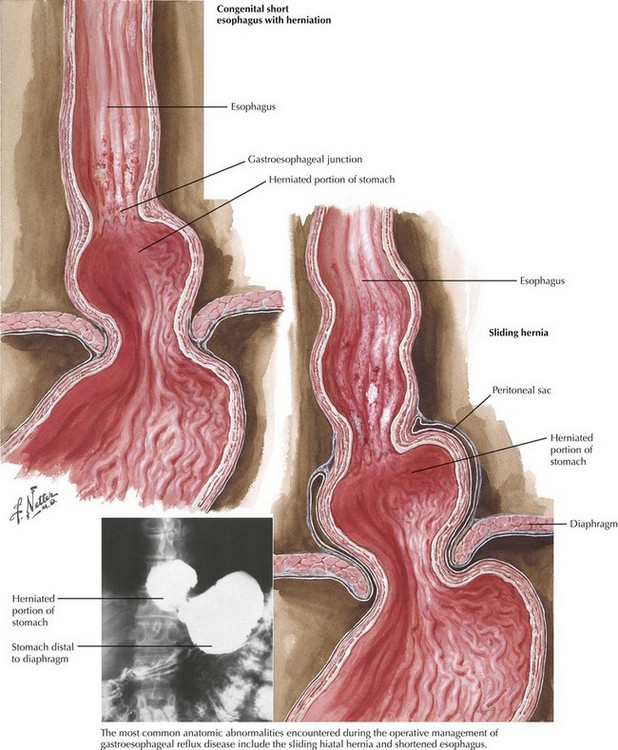

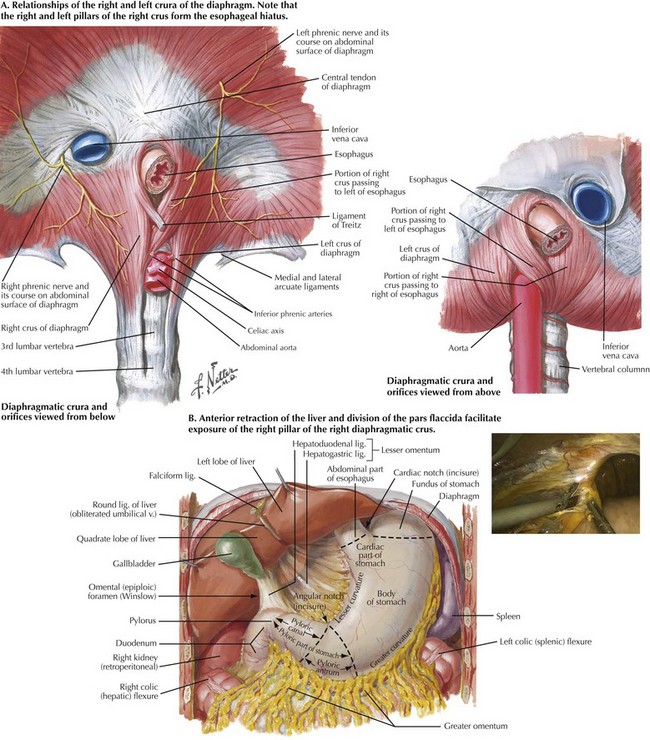

Chapter 6 The goals of successful surgical management of GERD are to restore the intraabdominal esophagus, repair the diaphragmatic crura, and reestablish a competent lower esophageal sphincter. A thorough understanding of hiatal anatomy, upper abdominal organ relationships, and mediastinal structures is critical to safe and effective operations for GERD (Figs. 6-1 to 6-3). Restoration of the lower esophageal sphincter is usually accomplished with a “floppy” 360-degree (Nissen) fundoplication formed around the distal esophagus. Upper endoscopy can reveal intraluminal pathology that can alter surgical decision making and can help ascertain anatomic changes that would impact the operation for GERD. The most common anatomic abnormality seen in this setting is the sliding, type I hiatal hernia (Fig. 6-4). Upper endoscopy can also reveal a shortened esophagus. The upper GI series also helps define anatomic abnormalities and is useful when more complex hiatal hernias are noted (types II-IV). Testing for acid exposure, nonacid reflux, and assessment of esophageal motility are also important nonimaging modalities that help in preoperative decision making. In most patients the fibers of the right crus of the diaphragm encircle the esophagus, making the right and left pillars of the right crus the pertinent structures of the esophageal hiatus (Fig. 6-5, A). Abdominal exposure of the right crus is usually obtained by retraction of the left lobe of the liver anteriorly and by incision of the filmy pars flaccida. The right pillar is usually readily identified and bluntly separated from the esophagus (Fig. 6-5, B). If a sizable hiatal hernia is encountered, the plane between the hernia sac and mediastinal structures is developed while preserving healthy endoabdominal fascia overlying the pillars of the crus.

Nissen Fundoplication

Surgical Principles

Preoperative Studies

Anatomy for Esophageal Mobilization

Diaphragmatic Crura (Superior and Inferior Views)

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Nissen Fundoplication