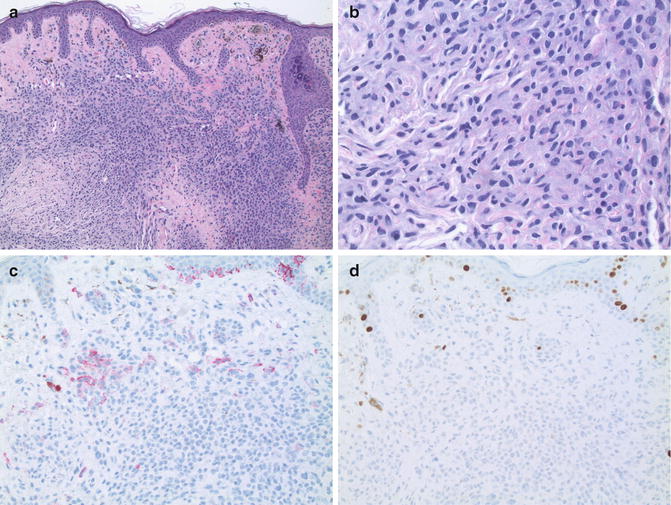

Fig. 8.1

Nevoid malignant melanoma. (a) The lesion displays circumscription, but cellular crowding (×10). (b) Note nuclear pleomorphism. Mitotic figures are scattered in the lesion including its base (×40). (c) Expression of gp100 in a patchy pattern (×20). (d) Increased Ki-67 expression toward the base of the lesion (×20)

Dermal nevoid melanoma cells may be predominantly nested or may form larger confluent sheets, the latter feature providing a valuable clue to the true diagnosis even at low magnification. In some cases, superficial nests of melanocytes may transition to smaller nests and more widely dispersed single cells in the deeper dermis [13]. This so-called “paradoxical maturation” pattern closely resembles the dermal architectural pattern typical of ordinary acquired melanocytic nevi (see below) and is perhaps the most misleading microscopic feature in these lesions. An associated dermal inflammatory cell infiltrate may or may not be present.

Fortunately, several important microscopic features help to distinguish nevoid melanoma from ordinary melanocytic nevi (summarized in Table 8.1). Most of these features become more apparent upon observation of the lesion at higher magnifications (Fig. 8.1b). First, nests of dermal melanocytes appear to be hypercellular compared to those of ordinary nevi. Unlike ordinary nevi, nevoid melanoma cells are typically tightly apposed (cellular crowding). This characteristic may be present throughout the lesion, but is lost toward the base of the lesion in tumors with paradoxical maturation. Second, nevoid melanoma cells display a greater degree of nuclear pleomorphism compared to melanocytic nevus cells. Nevoid melanoma cells often contain enlarged, hyperchromatic nuclei with irregular contours and variably prominent nucleoli. Third, nevoid melanoma cells display an increased proliferation rate, with mitotic figures scattered throughout the lesion, including the base. Nevoid melanomas may contain atypical mitotic figures, but their presence is not required for diagnosis. The presence of deep mitotic figures in a melanocytic lesion is of considerable importance since ordinary nevi lack this feature. Despite each of these important histological differences, nevoid melanomas may escape detection without the aid of additional studies.

Table 8.1

Microscopic features that help to distinguish nevoid malignant melanoma from ordinary melanocytic nevus

Diagnosis | Maturation | Hypercellular | Atypical | Mitoses |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Nevoid melanoma | + (Paradoxical)/– | + | + | + (Including base) |

Ordinary nevus | + | – | – | + (Rare, superficial)/– |

Ancient nevus | + | – | + | + (Rare, superficial)/– |

Nevus in pregnancy | + | + | – | + |

Invasive melanoma associated with a nevus | + (Nevus) | – (Nevus) | – (Nevus) | – (Nevus) |

– (Melanoma) | + (Melanoma) | + (Melanoma) | + (Melanoma) |

Immunohistochemical Features

As discussed in Chap. 4, evaluation of the dermal component of a melanocytic lesion for evidence of maturation and for proliferative activity may be useful for histologically challenging lesions. These considerations are especially true for nevoid melanoma [12].

Immunohistochemical labeling for the melanosomal glycoprotein gp100 (using antibody clone HMB-45) often shows an altered pattern in nevoid melanoma, even in lesions that display paradoxical maturation (Fig. 8.1c). Labeling may be completely absent, uniformly present throughout the lesion, or limited to a subpopulation of cells scattered in a haphazard or patchy pattern. Intensity of immunolabeling may be uniform, but often is variable in different areas of the lesion. The intraepidermal component (if present) may be labeled, thereby highlighting melanocytes in more superficial layers and making the diagnosis of melanoma more straightforward [14].

Labeling for the cell cycle marker Ki-67 (using antibody clone MIB-1) often is notably increased, highlighting the nuclei of cells throughout the lesion including its base (Fig. 8.1d). The percentage of labeled cells may be highly variable among lesions, but the distribution of labeling usually is haphazard and not limited to cells in the superficial dermis. Areas with increased numbers of labeled cells (hot spots) are common. As such, the pattern or distribution of labeling seems to be more important than the actual percentage of cells labeled. Similar observations have been made using another marker of cellular proliferation, proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) [12].

Melanocytic Nevus

Clinical Features

Ordinary melanocytic nevi are acquired lesions that typically appear early in life. Nevi may occur at any anatomic site affecting males and females alike. One epidemiologic study found an average of 36 ordinary nevi (2 mm in diameter or greater) on Caucasian patients who visited a dermatology clinic, but acknowledged that the number is highly variable among individuals [15]. Nevi may present as pigmented macules and papules that over time may become less pigmented. Most ordinary nevi are small, symmetrical, have a smooth border, and are evenly pigmented.

It is generally accepted that ordinary acquired nevi undergo a process of growth first within the epidermis (junctional nevus), followed by penetration into the dermis (compound nevus) [16]. Over time, the intraepidermal portion is lost and the lesion resides wholly in the dermis (intradermal nevus). This process usually is accompanied by gradual loss of pigmentation and by elevation of the lesion as melanocytes expand the dermis. Over the course of many years, some nevi undergo complete involution.

Microscopic Features

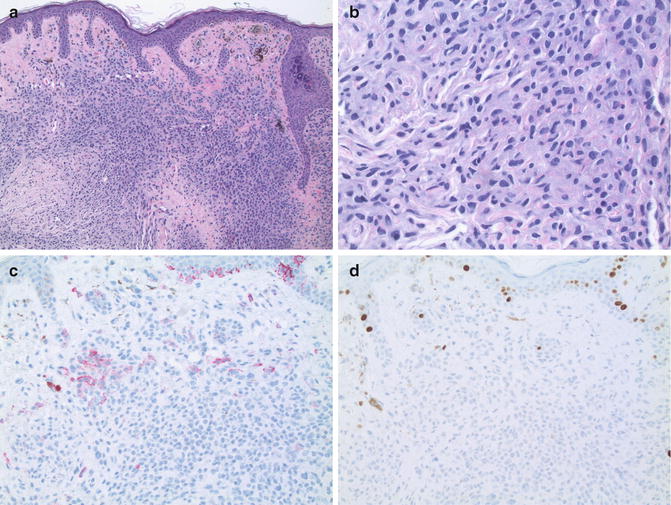

The clinical evolution of an ordinary nevus is associated with changes in its microscopic appearance as well. Junctional nevi contain melanocytes disposed singly and/or grouped into nests within the epidermis. The melanocytes have either an epithelioid or dendritic appearance. Many cells contain abundant cytoplasmic melanin. Nuclei may be enlarged and contain nucleoli, but are uniform in appearance and do not display significant pleomorphism or hyperchromasia. Compound and intradermal nevi display characteristic features of so-called “maturation” in the dermis. Nests of epithelioid melanocytes in the superficial dermis transition into areas with smaller nests and more dispersed smaller epithelioid or fusiform cells in the deeper dermis (Fig. 8.2a). Individual nest do not exhibit cellular crowding, and larger, confluent sheets of cells are uncommon. The change in architecture and cytologic morphology with progressive descent into the dermis is accompanied by visible loss of cytoplasmic melanin and by reduction in cellular size (Fig. 8.2b). Although a few mitotic figures may be present in the superficial dermal component of a nevus, few if any are present in the deeper portion. One study found that the nevi of younger patients were more likely to contain superficial dermal mitotic figures [17]. Ordinary benign melanocytic nevi are thus distinguished from nevoid melanomas by their lack of a sheet-like growth pattern, and by their cellular crowding, significant nuclear pleomorphism, and low mitotic rate. The only possible exception is that of nevi occurring in pregnant women, since they may have mitotic figures in the lesion (please see below).

Fig. 8.2

Ordinary benign melanocytic nevus. (a) The lesion displays circumscription and maturation, and lacks cellular crowding (×10). (b) Maturation with progressive descent into the dermis (×20). (c) Expression of gp100 is seen only in the superficial dermis (×20). (d) Ki-67 expression is limited to only a few cells (×20)

Immunohistochemical Features

In comparison to nevoid melanoma, ordinary nevi display an immunophenotype of maturation and low proliferative activity in their dermal component. Labeling for gp100 is limited to the intraepidermal (if present) and superficial nested, more pigmented dermal portions of the lesion (Fig. 8.2c). Patchy labeling throughout the lesion or labeling of cells toward the base is not observed. Importantly, any labeling present toward the base of a nevus should be interpreted with extreme caution since some melanophages may display immunoreactivity for gp100 as well as other melanosomal glycoproteins [18]. Similarly, labeling for Ki-67 is largely restricted to melanocytes in the epidermis and in the superficial dermal nests. Labeling (if present) is symmetrically distributed across the superficial portion. Very few, if any, melanocytes toward the base of a nevus are labeled (Fig. 8.2d) [14].

Differential Diagnosis: Melanocytic Nevus with “Ancient” Change

Clinical Features

Over time, ordinary melanocytic nevi may undergo changes that make their distinction from nevoid melanoma even more difficult. One example of this phenomenon is the so-called “ancient nevus” named for its histological similarities to ancient schwannoma [19, 20]. These nevi are almost exclusively long-standing papules on chronically sun-damaged skin. Head and neck are the most frequent sites of involvement. Based upon the usual clinical presentation and biological behavior of these lesions, most consider this histological change to be the result of cellular senescence within an otherwise ordinary benign melanocytic nevus.

Microscopic Features

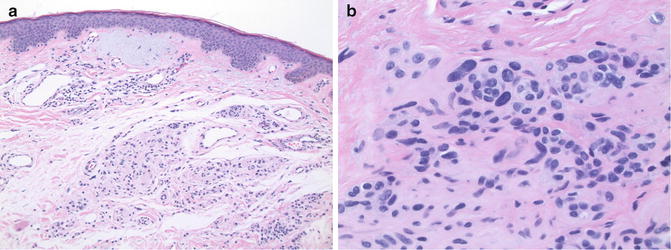

Observation at low magnification usually reveals the architectural features typical of a predominantly intradermal nevus in a background related to chronic sun exposure. These background actinic changes include variable degrees of epidermal atrophy, increased basal layer pigmentation, venous telangiectasia, perilesional collagen sclerosis, and solar elastosis (Fig. 8.3a). Intraepidermal melanocytes may be increased in number and uniformly distributed along the pigmented basal layer extending peripheral to the nevus, a feature reflective of the background actinic changes and not part of the nevus per se. Dermal melanocytes are nested in the superficial dermis, but are more dispersed at deeper levels in a typical architectural pattern of maturation. On higher magnification; however, ancient nevi contain scattered enlarged pleomorphic cells with hyperchromatic nuclei similar to those seen in nevoid melanoma (Fig. 8.3b). Nucleoli and/or nuclear pseudo-inclusions may be present in the atypical cells. The atypical melanocytes are haphazardly distributed in the lesion, giving the appearance of an altered pattern of maturation. However, unlike nevoid melanoma, ancient/senescent nevi are less cellular, and the atypical cells fewer in number. Few if any mitotic figures are present in the lesion, and those present are located in the upper regions of the lesion, a feature compatible with the theory that these lesions are in a state of cellular senescence.

Fig. 8.3

Ancient nevus. (a) The lesion is well circumscribed. Note prominent actinic changes (×10). (b) Atypical, pleomorphic cells scattered randomly in the dermis (×40)

Immunohistochemical Features

Although ancient/senescent nevi are less cellular and contain fewer atypical cells, their degree of cytologic atypia may be so severe as to warrant serious consideration of a nevoid melanoma or of a melanoma arising in association with a preexisting benign melanocytic nevus (see below). Fortunately, the gp100 and Ki-67 immunohistochemical features of ancient/senescent nevi are identical to those of ordinary nevi, exhibiting a typical maturation phenotype and low proliferation rate in the dermal melanocytes.

Differential Diagnosis: Melanocytic Nevus in Pregnancy

Clinical Features

Numerous studies have documented that long-standing ordinary melanocytic nevi may undergo dramatic clinical changes during pregnancy [21]. Nevi in pregnancy may grow rapidly, develop irregular borders, and/or display irregularities of pigmentation [22]. These changes are particularly concerning given that malignant melanoma during pregnancy is often biologically more aggressive. Many believe that these clinical and biological features are related to hormonal fluctuations associated with normal pregnancy. Identification of estrogen receptor-beta expression by melanocytes and melanoma cells has given support to this theory [23].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree