Condition

Appearance

Location

Histopathology

Associations

Sweet’s syndrome

Papules, plaques, nodules

Head, neck, upper extremity

Massive papillary dermal edema, nodular and diffuse neutrophilic infiltration with karyorrhexis

Fever, leukocytosis, arthralgias

Pyoderma gangrenosum

Pustule/vesiculopustule, ulcer

Lower extremity (pretibial); also breast, hand, trunk, head, neck, peristomal

Suppurative folliculitis, dense neutrophilic infiltrate; 50 % show leukocytoclastic vasculitis

50 % have underlying systemic disorder (Crohn’s, ulcerative colitis)

Erythema elevatum diutinum

Red-purple papules, plaques, nodules

Extensor surfaces of extremities

Leukocytoclastic vasculitis, polymorphonuclear neutrophils, onion-skin fibrosis

Associated with infection, neoplasia, and medications

Neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis

Erythematous edematous plaques

Can be localized or widespread

Infiltration of neutrophils within eccrine ducts, secretory coils + edema

Fever, neutropenia; malignancy, chemotherapy association

Generalized pustular psoriasis

Sheets of coalescing pustules on erythematous base

Flexural, crural, acral surfaces

Spongiform pustules

Fever, chills, malaise, arthralgias

Palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis

Pink to violaceous papules, plaques, nodules

Extensor surfaces of extremities (elbows, fingers)

Small vessel leukocytoclastic vasculitis, neutrophilic infiltrate

Arthritis

Sweet’s Syndrome

Sweet’s syndrome (acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis) is the prototype of the neutrophilic dermatoses. There are three clinical subtypes of Sweet’s syndrome based upon pathophysiology: classical (or idiopathic), malignancy-associated, and drug-induced. Classical Sweet’s syndrome comprises the majority of cases. Malignancy-associated Sweet’s syndrome most commonly occurs in association with hematologic malignancies (85 % of cases), predominantly acute myelogenous leukemia. Solid tumor associations, while less common, include carcinomas of the gastrointestinal tract, breast, and genito-urinary organs.

Clinically, Sweet’s syndrome presents abruptly with pyrexia, neutrophilia, and tender, erythematous papules that may progress into plaques or nodules (Fig. 35.1a–c). Cutaneous symptoms of the disease may be preceded by a period of several days or weeks of febrile illness, and fever may persist throughout the episode of dermatosis. Fever may also be absent in some cases. The cutaneous lesions may acquire a pseudovesicular appearance due to marked edema in the upper dermis. Dusky (Fig. 35.2) and bullous variants are more commonly associated with malignancy and may present similarly to features of pyoderma gangrenosum. Sweet’s syndrome lesions are often distributed asymmetrically and may be observed anywhere on the body, however, there is an increased observation of lesions on the head, neck, and upper extremities. Lesions typically resolve without scarring. Episodes of classic disease are commonly preceded by an upper respiratory or gastrointestinal infection, or vaccination. Extracutaneous manifestations include arthritis, arthralgias, conjunctivitis, episcleritis, and neutrophilic alveolitis. Granulocyte colony stimulating factor can produce similar cutaneous lesions (Fig. 35.3). Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsum of the hand is a variant of Sweet’s syndrome that exhibits a spectrum of manifestations from Sweet’s syndrome-like lesions to lesions more closely resembling pyoderma gangrenosum (Fig. 35.4). Histologically, it demonstrates a diffuse dermal neutrophilic infiltrate with karyorrhexis, variable ulceration, and subepidermal edema (Figs. 35.5 and 35.6).

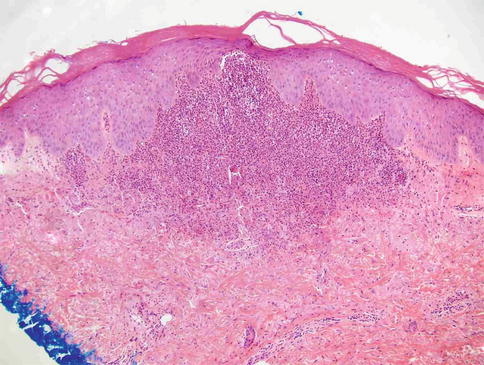

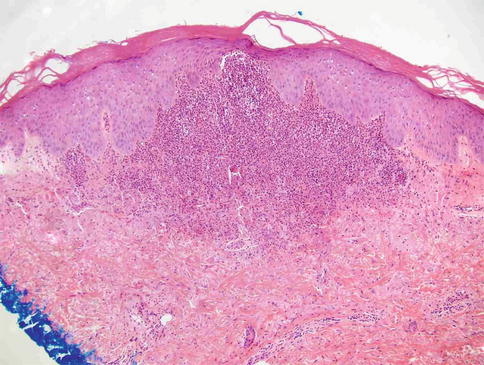

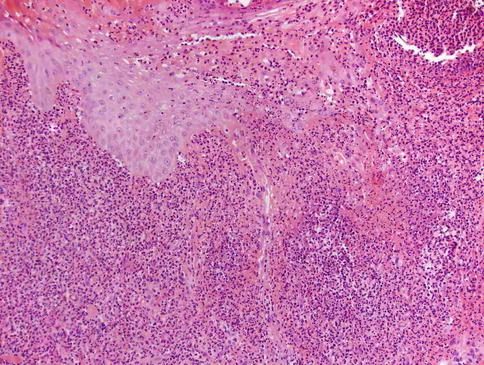

Fig. 35.1

(a–c) Sweet’s syndrome: (a) erythematous, edematous, tender plaque; (b) note massive papillary dermal edema; (c) diffuse neutrophilic infiltrate with karyorrhexis

Fig. 35.2

Dusky lesions of Sweet’s syndrome in a patient with leukemia

Fig. 35.3

Sweet’s-like reaction associated with GCSF therapy

Fig. 35.4

Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands

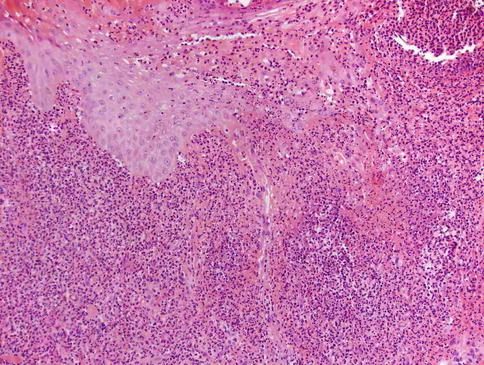

Fig. 35.5

Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands: Papillary dermal edema and neutrophilic infiltrate

Fig. 35.6

Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands: Ulceration, pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia of the epidermis and neutrophilic infiltrate

The pathogenesis of Sweet’s syndrome has not been fully elucidated. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor may be involved, and involvement of interleukins (IL)-1, -3, -6, and -8 has also been postulated. Histopathologic changes include massive edema of the dermal papillae and dermal infiltration of mature neutrophils with karyorrhexis. Leukocytoclastic vasculitis may be present focally. Eosinophils, lymphocytes, and histiocytes may be present within the inflammatory infiltrate.

Many drugs have been implicated as causes of Sweet’s syndrome (Table 35.2). Early reports of drug-induced Sweet’s syndrome involved trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, however, the most widely implicated medication reported in association with this condition is granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF). The syndrome typically develops approximately 2 weeks after exposure of the offending drug. The syndrome is also known to recur with re-administration of the agent, which can be a useful diagnostic characteristic. Further, discontinuation of the causative agent causes improvement of disease manifestations. Other medications that have been reported to induce Sweet’s syndrome include tretinoin, specific vaccines (e.g. pneumococcal), lithium, furosemide, hydralazine, oral contraceptives, minocycline, azathioprine, imatinib, and bortezomib.

Table 35.2

Drugs causing Sweet’s syndrome

Antibiotics | Minocyclinea Nitrofurantoin Fluoroquinolones Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole |

Antiepileptics | Carbemazepine Diazepam |

Antineoplastics | Bortezomib Imatinib mesylate Lenalidomide |

Colony stimulating factors | Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) Granulocyte-macrophage-colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) |

Contraceptives | Levonorgestrel/ethinyl estradiol (Triphasil) Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (Mirena) |

Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory agents | Celecoxib Diclofenac |

Retinoids | All-trans retinoic acid 13-cis-retinoic acid |

Vaccines | H1N1 Influenza Pneumoccocal |

Others | Abacavir Azacitidine Azathioprine Clozapine Furosemidea Hydralazinea Lithium Propylthiouracil |

The differential diagnosis for Sweet’s syndrome includes infection, reactive erythemas, and vasculitides. Infections to be excluded include bacterial pyoderma, deep fungal infection, atypical mycobacterial infection, and leishmaniasis. In patients with leukemia, it is important to distinguish paraneoplastic Sweet’s syndrome from leukemia cutis. This may be difficult in some patients, as Sweet’s syndrome may recruit neoplastic as well as benign granulocytes. The evaluation of patients with Sweet’s syndrome involves a thorough history and physical examination to rule out underlying diseases. Appropriate laboratory studies include a complete blood count with differential, comprehensive metabolic panel, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, anti-nuclear antibodies, rheumatoid factor, urine analysis, and serum immunofixation electrophoresis. A skin biopsy should be performed for histopathologic analysis. If infection is suspected, tissue cultures may be necessary.

First-line therapy for Sweet’s syndrome is systemic corticosteroids at a dose of 0.5–1 mg/kg/day with a taper over 2–6 weeks. Some patients may require treatment for 2–3 months with tapering doses, but when prolonged courses are needed alternative therapy should be considered. Systemic potassium iodine and colchicine are also considered first-line agents and may be more suitable for patients with chronic disease. Approximately one-third of patients experience recurrence and require the addition of a steroid-sparing agent. These second-line agents include dapsone, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha antagonists, indomethacin, and cyclosporine. In regard to drug-induced Sweet’s syndrome, discontinuation of the offending medication results in spontaneous improvement and resolution of the syndrome.

Bowel-Associated Dermatosis-Arthritis Syndrome

Bowel-associated dermatosis-arthritis syndrome is a neutrophilic dermatosis that closely resembles Sweet’s syndrome clinically and histologically. It presents with fever, flu-like symptoms, and inflammatory cutaneous eruptions. The condition is associated with bowel bypass surgery and inflammatory bowel disease. It is thought to be caused by an immune response to bacterial antigens in the blind loop of bowel with subsequent immune complex formation. Clinically, this syndrome presents with sterile erythematous macules which may evolve into papular, vesicular, and pustular lesions. Lesions are frequently observed on the upper extremities and chest. Histopathological evaluation exhibits infiltration of mature neutrophils in the dermis with karyorrhexis and prominent papillary dermal edema, just as in Sweet’s syndrome. Acute treatment involves corticosteroids, however antibiotic therapy and elimination of the blind loop of bowel may be necessary.

Pyoderma Gangrenosum

Pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) is a cutaneous disease that presents initially as a pustule or vesiculopustule and progresses to an ulcer with an undermined border (Fig. 35.7). Ulcers are recurrent, painful, and commonly demonstrate a cribriform pattern of pitted necrosis. There are four major clinical subtypes of pyoderma gangrenosum: ulcerative, pustular, bullous, and vegetative (Table 35.3). Peak incidence occurs between 20 and 50 years, with women more frequently affected than men. It most often occurs on the lower legs, with predominance on the pretibial area. It is also observed on the breast, hand, trunk, head, neck, and peristomal areas. Notably, PG exhibits pathergy, occurring in sites of trauma such as needle sticks. Another manifestation of pathergy is that debridement typically exacerbates the condition. As many as 50 % of affected patients have an underlying systemic disorder such as ulcerative colitis (10–15 % of cases), Crohn’s disease, hepatitis C, seronegative rheumatoid arthritis, spondylitis, and various lymphoproliferative disorders. Of importance, PG can also be attributed to drug therapies, with reported causative agents such as propylthiouracil, pegfilgastrim (G-CSF), gefinib (an epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor), sunitinib, adalimumab, infliximab, and isotretinoin.