Neurobiology of Nonpsychotic Illnesses

Ann Futterman Collier

Key Questions

![]()

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Copstead/

Neurobiological mechanisms of mental disorders that do not cause psychosis may prove to be more similar than different from those of mental disorders associated with psychosis. These conditions already show similarity in that they are categorized by altered neuronal structures and functioning, genetic risk factors, and neurotransmission dysregulation. A major difference between psychotic and nonpsychotic illnesses is that individual variations in nonpsychotic conditions can be extensive. Greater individual variations increase the difficulty of defining the hallmark symptomatology and neurobiological basis of the condition. In addition, much has been learned about the neurobiological impact of stress response systems in psychotic illnesses, whereas the impact of stress response systems in nonpsychotic illnesses is less well understood. In the past, simple contrasts, such as comparing schizophrenia with eating disorders, invited the false assumption that one disorder may be more or less serious than another. For the affected person, such comparisons are unhelpful. Mental disorders, by definition, cause profound suffering and impairment.

Anxiety Disorders

This section presents four anxiety disorders: panic disorder (PD), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).1 Although anxiety disorders have many similar physical symptoms, they differ greatly in terms of symptom onset triggers, symptom duration, and symptom management. Because anxiety disorders are primarily characterized by physical symptoms, physical illnesses (e.g., hyperthyroidism) and medication reactions (e.g., antidepressants, steroids, anticholinergic medications) must be ruled out before a diagnosis of anxiety disorder can be made. Together with depression, anxiety disorders are the most common of all psychiatric illnesses, and aside from social phobia and OCD, occur two times more often in women than in men.

Panic Disorder (PD)

Panic disorder (PD) is characterized by acute episodes of anxiety symptoms that are unexpected, sudden, and recurrent and generate intense feelings of fear. Sudden symptom onset can cause affected persons to seek emergency health care for what they believe is a cardiac arrest, respiratory arrest, or “nervous breakdown.” Panic attacks can be situation-bound, and hence occur in other anxiety disorders such as a specific phobias, social phobia, and PTSD.2

Depending on the subtype, panic disorder is diagnosed two to three times more often in women than in men.1 Rates of 1% to 2% are most commonly reported. Initial onset usually occurs in late adolescence or young adulthood, with a mean age of onset of 26.6 years. Initial symptom onset in older age adults is less typical.

Etiology and neurobiology

The risk of anxiety disorder symptom onset has been associated with moderate genetic, psychological, and biological system alterations.3 Family, twin, and adoptive family studies have consistently shown a strong genetic liability for these disorders. However, experts now speculate that the etiology question is no longer nature versus nurture. Current models seek to explain the interactions of nature and nurture that can create susceptibility to anxiety. Brain regions that underpin the experiences of fear, anxiety, and stress are thought of as circuits that can be shaped and altered by a wide range of forces. Neurobiological conditioning is one force shown to impact such circuits and thus is of particular importance to understanding the development of anxiety disorders.

Brain serotonin activity has been revealed to interact with both genes and environment, and these interactions contribute to what has come to be referred to as synaptic plasticity.3 In this way, genes are linked with brain cell neurochemistry and psychological characteristics such as temperament. More specifically, evidence of genetic variability in negative emotions, such as anxiety, has been found in studies of serotonin transporter cells. In this research, gene variability is in gene allele length. For example, family studies have shown that siblings with serotonin transporter cells with the short-form gene allele had higher neuroticism scores than their siblings with the long-form gene allele. Research aimed at gene typing mental disorders clearly is in its infancy and findings such as these are inconclusive, but they demonstrate the possibility of genetics-based neurobiological models of anxiety.

Susceptible persons who breathe air with high levels of carbon dioxide will experience an acute onset of panic anxiety symptoms.4 A small study of persons with panic anxiety disorder, using an infusion of doxapram (respiratory stimulant) to cause profound hyperventilation, examined the effectiveness of cognitive interventions to reduce respiratory anxiety symptoms.5 Cognitive interventions were designed to minimize misinterpretation of drug-induced hyperventilation as a sign of danger and thereby reduce the odds of the respiratory stimulant triggering panic anxiety. Breath-by-breath analyses of the patients and healthy controls were performed. The researchers5 hypothesized that if the respiration anxiety symptoms were the result of dysregulation within the brain respiratory control center, cognitive interventions would not be particularly effective. They found that less fearful thinking did reduce panic, but some respiratory anxiety symptoms persisted despite less fearful thinking. In other words, respiratory anxiety symptoms appeared to result both from anticipatory anxiety and from dysregulation within the brain respiratory center.

Surges of physiologic activation and physiologic instability are thought to be the hallmark neurobiological processes underlying panic anxiety disorder.6 Multiple organ systems, including the cardiovascular and respiratory systems, are thought to be involved. Observations such as these help to explain why, for example, caffeine triggers panic anxiety symptoms in susceptible individuals. Physiologic instability may prove to be the key to identifying a genetics-based marker for susceptibility to panic. However, the biopsychological marker for the disorder is likely to be the overinterpretation of physical anxiety symptoms (e.g., sudden increase in heart rate) as life threatening. This thinking, referred to as learned panic, is thought to result from inordinately high levels of life stress in early childhood.

Overwhelming life stress can increase the level of circulating glucocorticoids (stress hormones) and stimulate the release of glutamate (which inhibits neurogenesis).7 Early-childhood life stress, specifically abuse and neglect, has been studied as a possible predictor of various adult-onset anxiety disorders. These models are based on altered serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine neurotransmission; glutamate release; and physiologic instability. Repeated and prolonged childhood exposure to overwhelming stress is thought to create adult susceptibility to anxiety disorders. The leading theory is that early life stress leads to an overspecialized or excessive stress response.

Early life stress is thought to produce adult susceptibility to anxiety by altering critical neuron structures and functioning during this critical stage of human growth and development. Brain regions most vulnerable to alteration as a result of early life stress include the hippocampus (glucocorticoid receptors), amygdala (γ-aminobutyric acid [GABA] and benzodiazepine receptors), corpus callosum (glial cells critical to myelination), cerebellar vermis (glucocorticoid receptors), and the prefrontal cortex (glucocorticoid receptors, dopamine projections, and inhibition of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal [HPA] axis activation).7,8 When the developing brain of a young child is exposed to overwhelming life stress, the stress response system appears to adapt by overbuilding or building additional brain stress response pathways. Later, under less stressful adult circumstances, this overbuilt stress response system becomes maladaptive. Like a very large overpowered car on a small, winding road, the overbuilt stress response system could become the source of physiologic instability that has come to be associated with panic anxiety.9

Clinical manifestations

With panic disorder, no single experience consistently triggers symptom onset, although the first attack(s) frequently occur(s) during a life-threatening illness or accident, loss of a close interpersonal relationship, or separation from family. After that, they can occur during any routine activity, from reading to driving. When patients experience their first few panic attacks they frequently think they are either having a heart attack or losing their mind and it is common to seek emergency medical treatment.2 Physical symptoms are most prominent and emphasized, and include respiratory distress, heart palpitations, tachycardia, pounding heart, chest pain, smothering or choking sensation, dizziness, lightheadedness, faintness, sweating, trembling, shaking, hot flushes, chills, numbness, tingling, nausea, abdominal distress, and urinary frequency.2 Psychological and cognitive symptoms include expressed fears of dying, fear of cardiac arrest, fear of losing control, fear of nervous breakdown, derealization, depersonalization, and perceptual distortions. Behavioral symptoms include hyperkinesis, pressured speech, and exaggerated startle response. The attacks usually last between 5 and 20 minutes, although they can last as long as an hour. They can happen in a wavelike manner, so that they occur successively, or as described earlier, as part of another clinical disorder. Some people experience such severe anticipatory anxiety that it is hard to separate when the attack starts and ends, so that the panic attack is experienced as continuous.

Panic disorder is characterized by two important psychological symptoms: anticipatory anxiety and avoidance anxiety. Anticipatory anxiety refers to fearful expectation of panic anxiety onset. People with the disorder tend to develop a morbid dread of events or experiences that they come to believe might trigger panic anxiety. Avoidance anxiety refers to personal strategies used to increase feelings of control and thereby decrease the risk of panic anxiety. Persons with panic disorder strive to avoid situations and circumstances they associate with their symptoms. This helps to explain why panic disorder and agoraphobia (the phobic avoidance of public spaces beyond personal control, e.g., airports and shopping malls) often coexist.

Treatment

Panic anxiety disorder can be effectively managed with cognitive-behavioral therapy aimed at reducing fearful thinking and desensitization of cognitive and physical stress responses. When panic symptoms are disabling, medication for symptom management is recommended.2 Long-acting benzodiazepines, such as clonazepam, are the sedatives of choice when short-term calming and symptom relief are mandatory. Tolerance to benzodiazepines develops with continuous use regardless of dosage. Misuse of benzodiazepines represents a serious health hazard. Although these drugs are useful in blocking the panic attack, they do not always decrease the anticipatory anxiety and avoidance, especially when drug regimens are initially undertaken. Many atypical psychiatric medications that can target serotonin, dopamine, or norepinephrine receptors have been clinically tested and shown to be effective treatment for anxiety symptoms. Examples of such medications found to be helpful include paroxetine, sertraline, citalopram, and fluoxetine. Unless contraindicated, β-blocker medications that dampen physical anxiety symptoms may also be helpful.

Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD)

GAD is characterized by chronic and persistent worry, as well as physical anxiety symptoms. The anxiety is excessive, pervasive, difficult to control, and associated with marked distress or impairment.1 Typically, the patient experiences multiple anxiety symptoms including restlessness, fatigue, impaired concentration, irritability, muscle tension, muscle pain, and disturbed sleep.10 Lacking clear symptom onset patterns, GAD is easily overlooked or misdiagnosed. GAD is a chronic condition, and earlier onset is associated with more overall impairment. There is high comorbidity with substance use and other anxiety disorders, depression, and personality disorders. Higher rates of GAD occur in women than men. The prevalence of GAD does not decline with age, and appears to account for most of the anxiety disorders in the elderly.11

Etiology and neurobiology

GAD10 differs from other anxiety disorders in that the cognitive, psychological, and behavioral symptoms are relatively constant. Psychoanalysts developed most of the original etiologic theories concerning persistent worry. What now is referred to as persistent worry was then described as anxious expectation. Even at that early stage of discovery, it was apparent that generalized anxiety rarely occurred without comorbid conditions such as depression. This psychodynamic view of generalized anxiety prevailed until the late 1980s and early 1990s. More recently, cognitive theorists view GAD as having its origins in early attachment to the primary caretaker. Conceptually, worry is seen as an avoidance strategy for negative affect; as a distraction from realistic and proximal threats that need immediate solutions; and as a coping method to “prevent” the feared outcome, such as occurs with magical thinking. Unlike panic disorder, where the worry is more typically about physical catastrophes, in GAD, worries are more about interpersonal confrontation, competence, and acceptance. Technologically advanced research methods have now made it possible to precisely define GAD symptoms in terms of their actual qualities, intensity, and duration, but physical GAD symptoms continue to be viewed as somatic expressions of psychological problems.10

Unlike other anxiety disorders, GAD onset typically is gradual with symptom duration measured in years. As has been observed with other anxiety disorders, vulnerability to GAD likely is inherited. Twin and family study findings indicate a 30% increase in risk of GAD among the relatives of persons with the disorder.2 Efforts to describe the neurobiological basis of GAD will no doubt be greatly advanced by theoretical models of inherited vulnerability as well as improved understanding of GAD symptoms. The most important unanswered question likely will have to do with the fact that the alterations in brain structure and functioning shown to be associated with GAD also are consistent with alterations observed with other disorders.

Preliminary positron emission tomography (PET) studies measuring brain glucose metabolism rates in GAD have shown higher than normal rates in patients at rest.12 With GAD, apparently some brain regions undergo both increases and decreases in glucose metabolism rates. This mixed response is most apparent in the frontal and cingulate areas of the cortex, the brain region associated with worry and hypervigilance. Findings such as these lend support to the basic GAD explanatory hypothesis of anxiety symptoms as manifestations of hyperactive brain circuits. Just the opposite condition (hypoactive brain circuits) is thought to be the fundamental basis of depressive disorders.12

Neurotransmitter findings with GAD, as with other disorders that produce mood, thinking, and behavior symptoms, point to alterations in GABA receptors, benzodiazepine receptors, norepinephrine systems, serotonin systems, HPA axis activation, and plasma cortisol levels. Thus far, no specific alterations that can consistently explain GAD symptoms have been identified.12 Nevertheless, one interesting observation shows considerable promise. At rest, no obvious alterations in neurotransmission are noted in GAD patients. Only when subjected to laboratory activities designed to induce stress responses is significant neurotransmitter overactivity observed. Evidence of norepinephrine receptor down-regulation lends additional support to this stress response model. Attempting to modulate overactive responses, receptor down-regulation is thought to occur automatically when subjected to prolonged, recurrent, excessive, or hyperactive neurotransmitter activity.

Whereas norepinephrine activity is thought to be associated with physical symptoms of GAD, anticipatory and avoidance symptoms are thought to be associated with activity along a key serotonin pathway linking the amygdala and frontal cortex. As might be expected, insufficient serotonin activity in specific brain regions is thought to be associated with GAD. Given the obvious symptom overlap between stress and anxiety, hyperactivity within the HPA axis and high plasma cortisol levels continue to be leading models in GAD research. Much of the difficulty in defining the neurobiological basis of GAD has to do with significant individual variations in GAD symptomatology. Uncontrollable worry (frontal cortex) is the only symptom likely to show meaningful consistency over time and from individual to individual. A second major research difficulty has to do with the frequency with which GAD symptoms co-occur with depression symptoms—so much so that some experts now view mixed depression-anxiety as a specific disorder.2

Clinical manifestations

The symptoms of GAD typically fall into two categories: apprehensive expectation and worry, and physical symptoms. The worry is often about minor issues, where the person anticipates the worst possible outcome, and finds it difficult to control. No areas of life are excluded, and worry is not limited to any single area of concern (e.g., children). Physical symptoms vary greatly, but people often feel “keyed up,” which results in muscle tension, lightheadedness, sweating, palpitations, dizziness, and stomach distress. Concentration is typically severely impaired, and irritability is common. Diffuse anticipatory anxiety, avoidance anxiety, and dysphoria are common. Behavioral symptoms include severe sleep disturbance and fatigue. Although much of the behavior associated with GAD is likely to be the result of maladaptive methods of coping with physical and psychological GAD symptoms, impaired social and academic/employment functioning are common.

Pharmacologic treatment

Effective psychological and drug treatments for GAD can be relatively complex. When alcohol is comorbid, it may limit the effectiveness of treatment and/or delay the onset of benefits. Delayed onset of benefits from treatment is likely to be seen when GAD symptoms are long-standing and highly disabling. Lastly, neurobiological research findings indicate that effective drug treatment is likely to require one or more medications that are reliable modulators of multiple neurotransmission systems across multiple brain regions. Medications shown to relieve and in some cases remit GAD symptoms include long-acting benzodiazepines (e.g., clonazepam), partial serotonin (i.e., 5-hydroxytryptamine, 5-HT1A) agonists (e.g., buspirone), tricyclic antidepressants (e.g., imipramine), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (e.g., sertraline), serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (e.g., venlafaxine), and long-acting β-blockers (e.g., propranolol).13

Nonpharmacologic treatment

Cognitive-behavioral therapy combined with relaxation training appears to be more effective than nondirective and supportive therapy for the treatment of GAD. In addition, cognitive-behavioral therapy is also superior to behavioral therapy alone.2

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD)

Although listed here as an anxiety disorder, OCD will very likely be classified under a new category of disorders called Obsessive Compulsive and Related Disorders in the upcoming DSM-5.14 The inclusion under Anxiety Disorders has occurred because anxiety is frequently associated with the symptoms and because yielding to compulsions temporarily decreases anxiety. However, recent research suggests that OCD more aptly belongs with a separate grouping of compulsive spectrum disorders.2 Typically the disorder is characterized by persistent, involuntary thoughts that then provoke anxiety and involuntary anxiety management rituals. Unlike the acute onset and short duration of panic anxiety symptoms or the chronic symptoms of GAD, the obsessions and compulsions that characterize OCD are localized but nevertheless impact all areas of functioning.

More than 50% of patients diagnosed with OCD have a chronic and progressive course, 25% to 33% have a fluctuating course, and less than 15% have a phasic course with periods of complete remission. Occasionally, there can be sudden onset of symptoms, especially when there is a neurologic basis for the illness. Predictors for poor prognosis include an early age of onset, longer duration of the illness, presence of obsessions and compulsions, poorer baseline social functioning, and presence of magical thinking.2

People with OCD typically strive to avoid disclosing their symptoms to relatives, friends, and health professionals. As such, accurate incidence and prevalence statistics are nearly impossible to determine. The lifetime OCD prevalence rate for the general population is 2.2%, whereas the risk in first-degree relatives is 9.2%.2 Some experts consider this general-population estimate to be an underestimate. OCD is a severe disorder that typically begins in adolescence or early adulthood; the median age of symptom onset is about 23 years. However, 31% of the initial episodes have reportedly occurred between 10 and 15 years of age.2 Although there is no gender difference in the prevalence rates of OCD, there is some indication that OCD might have its onset or worsen during pregnancy.15 In addition, of children diagnosed with OCD, 70% are males.

Etiology and neurobiology

Neurobiological research findings indicate that there is a strong genetic or inherited risk of OCD.2 Twin and family studies show a greater degree of concordance for OCD among monozygotic twins compared to dizygotic twins. Once an adult family member has been diagnosed with the disorder, child relatives are more likely to be diagnosed. Depression, anorexia, and Tourette syndrome are common OCD comorbid disorders. Close links between OCD and the hereditary neurologic disorder Tourette syndrome have been reported, but it is not clear whether this link represents an increased risk of OCD or whether Tourette syndrome and OCD are related in some other way.

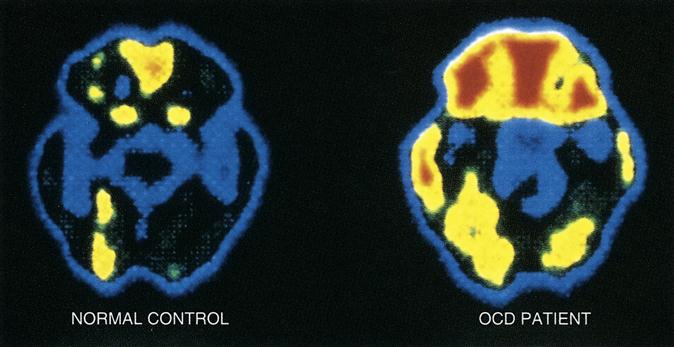

OCD studies using PET brain scans have shown significant increases in glucose metabolism rates in the frontal lobes, caudate nucleus, and cingulate gyrus regions of the brain (Figure 49-1). These brain regions are directly associated with response to strong emotions. However, several OCD models of altered brain functioning have been hypothesized. One model proposes that a causal pathway for OCD exists between the frontal cortex region and basal ganglia region of the brain. This model draws on the observation that similar illnesses with well-defined etiologic factors have been shown to involve both cognitive and motor brain regions. Predictably, serotonin activity dysregulation and dysfunction also represent possible OCD models.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree