56

Nematodes

CHAPTER CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Nematodes (also known as Nemathelminthes) are round-worms with a cylindrical body and a complete digestive tract, including a mouth and an anus. The body is covered with a noncellular, highly resistant coating called a cuticle. Nematodes have separate sexes; the female is usually larger than the male. The male typically has a coiled tail.

The medically important nematodes can be divided into two categories according to their primary location in the body, namely, intestinal and tissue nematodes.

(1) The intestinal nematodes include Enterobius (pinworm), Trichuris (whipworm), Ascaris (giant roundworm), Necator and Ancylostoma (the two hookworms), Strongyloides (small roundworm), and Trichinella. Enterobius, Trichuris, and Ascaris are transmitted by ingestion of eggs; the others are transmitted as larvae. There are two larval forms: the first- and second-stage (rhabditiform) larvae are noninfectious, feeding forms; the third-stage (filariform) larvae are the infectious, nonfeeding forms. As adults, these nematodes live within the human body, except for Strongyloides, which can also exist in the soil.

(2) The important tissue nematodes Wuchereria, Onchocerca, and Loa are called the “filarial worms,” because they produce motile embryos called microfilariae in blood and tissue fluids. These organisms are transmitted from person to person by bloodsucking mosquitoes or flies. A fourth species is the guinea worm, Dracunculus, whose larvae inhabit tiny crustaceans (copepods) and are ingested in drinking water.

The nematodes described above cause disease as a result of the presence of adult worms within the body. In addition, several species cannot mature to adults in human tissue, but their larvae can cause disease. The most serious of these diseases is visceral larva migrans, caused primarily by the larvae of the dog ascarid, T. canis. Cutaneous larva migrans, caused mainly by the larvae of the dog and cat hookworm, Ancylostoma caninum, is less serious. A third disease, anisakiasis, is caused by the ingestion of Anisakis larvae in raw seafood.

In infections caused by certain nematodes that migrate through tissue (e.g., Strongyloides, Trichinella, Ascaris, and the two hookworms Ancylostoma and Necator), a striking increase in the number of eosinophils (eosinophilia) occurs. Eosinophils do not ingest the organisms; rather, they attach to the surface of the parasite via IgE and secrete cytotoxic enzymes contained within their eosinophilic granules. Host defenses against helminths are stimulated by interleukins synthesized by the Th-2 subset of helper T cells (e.g., the production of IgE is increased by interleukin-4, and the number of eosinophils is increased by interleukin-5 [IL-5]) (see Chapter 58). Cysteine proteases produced by the worms to facilitate their migration through tissue are the stimuli for IL-5 production.

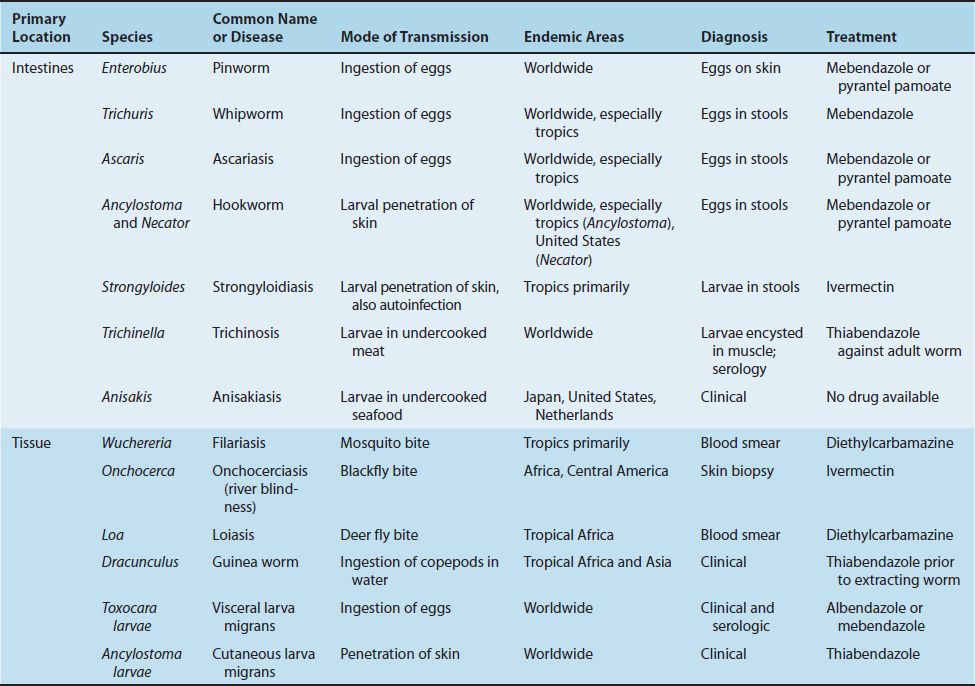

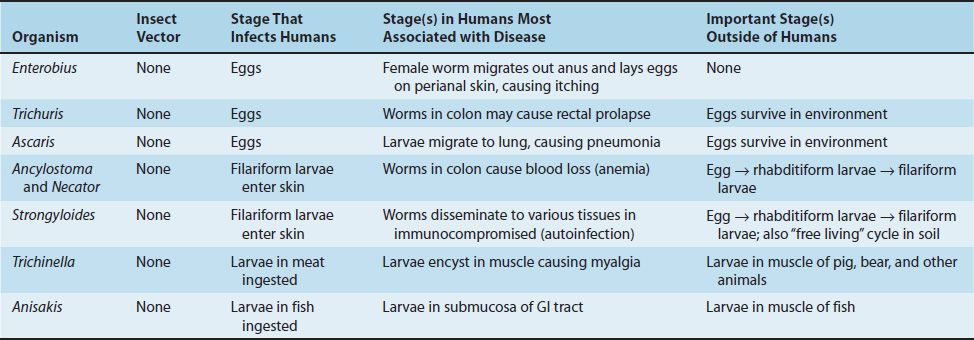

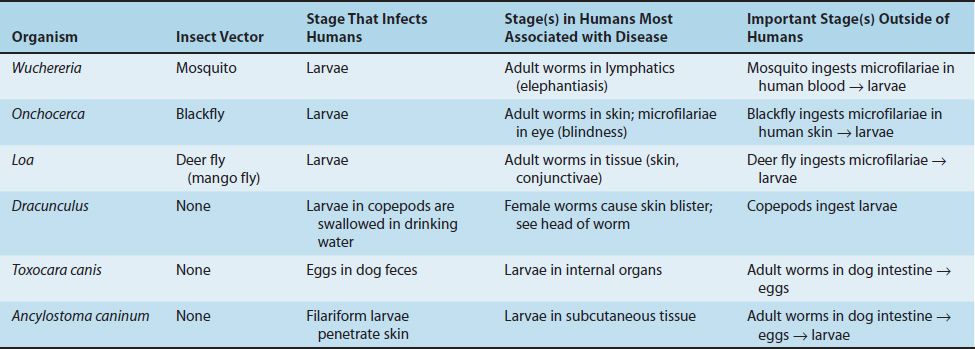

Features of the medically important nematodes are summarized in Table 56–1. The medically important stages in the life cycle of the intestinal nematodes are described in Table 56–2, and those of the tissue nematodes are described in Table 56–3.

INTESTINAL NEMATODES

ENTEROBIUS

Disease

Enterobius vermicularis causes pinworm infection (enterobiasis).

Important Properties

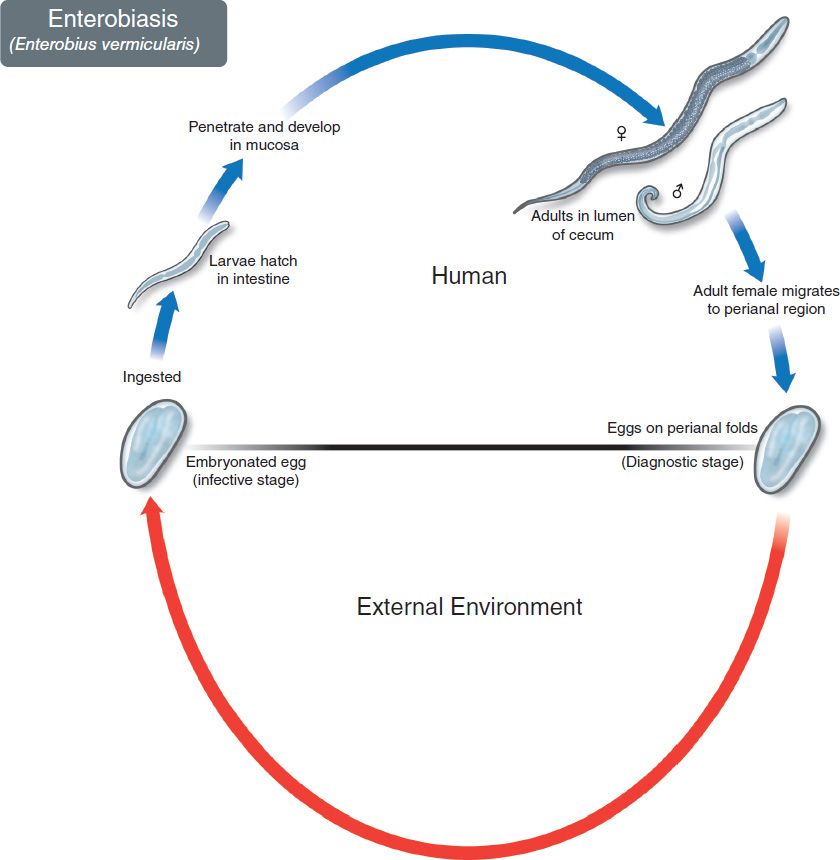

The life cycle of E. vermicularis is shown in Figure 56–1. Infection occurs only in humans; there is no animal reservoir or vector. The infection is acquired by ingesting the worm eggs. The eggs hatch in the small intestine, where the larvae differentiate into adults and migrate to the colon. The adult male and female worms live in the colon, where mating occurs (Figure 56–2A). At night, the female migrates from the anus and releases thousands of fertilized eggs on the perianal skin and into the environment. Within 6 hours, the eggs develop into embryonated eggs (Figures 56–3A and 56–4) and become infectious. Reinfection can occur if they are carried to the mouth by fingers after scratching the itching skin.

FIGURE 56–1 Enterobius vermicularis. Life cycle. Top: Blue arrow at top left shows eggs being ingested. Adult pinworms form in colon. Female migrates out anus and lays eggs on perianal skin. Bottom: Red arrow indicates survival of eggs in the environment. (Figure courtesy of Public Health Image Library, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.)

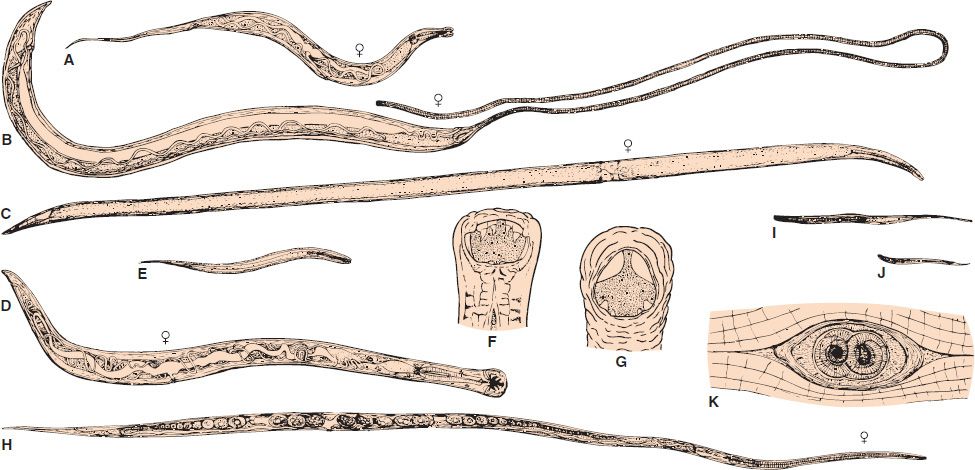

FIGURE 56–2 A: Enterobius vermicularis female adult (6×). B: Trichuris trichiura female adult. Note the thin anterior (whiplike) end (6×). C: Ascaris lumbricoides female adult (0.6×). D: Ancylostoma duodenale female adult (6×). E: Ancylostoma duodenale filariform larva (60×). F: Ancylostoma duodenale head with teeth (25×). G: Necator americanus head with cutting plates (25×). H: Strongyloides stercoralis female adult (60×). I: Strongyloides stercoralis filariform larva (60×). J: Strongyloides stercoralis rhabditiform larva (60×). K: Trichinella spiralis cyst containing two larvae in muscle (60×).

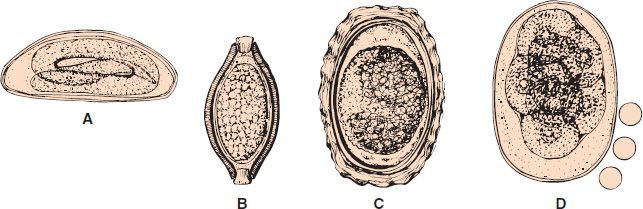

FIGURE 56–3 A: Enterobius vermicularis egg. B: Trichuris trichiura egg. C: Ascaris lumbricoides egg. D: Ancylostoma duodenale or Necator americanus egg (300×). (Circles represent red blood cells.)

FIGURE 56–4 Enterobius vermicularis—eggs. Long arrow points to an egg of the pinworm, Enterobius vermicularis recovered on “Scotch tape.” Short arrow points to the embryo inside the egg. (Figure courtesy of Public Health Image Library, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.)

Pathogenesis & Clinical Findings

Perianal pruritus is the most prominent symptom. Pruritus is thought to be an allergic reaction to the presence of either the adult female or the eggs. Scratching predisposes to secondary bacterial infection.

Epidemiology

Enterobius is found worldwide and is the most common helminth in the United States. Children younger than 12 years of age are the most commonly affected group.

Laboratory Diagnosis

The eggs are recovered from perianal skin by using the Scotch tape technique and can be observed microscopically (Figure 56–4).

Unlike those of other intestinal nematodes, these eggs are not found in the stools. The small, whitish adult worms can be found in the stools or near the anus of diapered children. No serologic tests are available.

Treatment

Either mebendazole or pyrantel pamoate is effective. They kill the adult worms in the colon but not the eggs, so retreatment in 2 weeks is suggested. Reinfection is very common.

Prevention

There are no means of prevention.

TRICHURIS

Disease

Trichuris trichiura causes whipworm infection (trichuriasis).

Important Properties

Humans are infected by ingesting worm eggs in food or water contaminated with human feces (see Figures 56–3B and 56–5). The eggs hatch in the small intestine, where the larvae differentiate into immature adults. These immature adults migrate to the colon, where they mature, mate, and produce thousands of fertilized eggs daily, which are passed in the feces. Eggs deposited in warm, moist soil form embryos. When the embryonated eggs are ingested, the cycle is completed. Figure 56–2B illustrates the characteristic “whiplike” appearance of the adult worm.

Pathogenesis & Clinical Findings

Although adult Trichuris worms burrow their hairlike anterior ends into the intestinal mucosa, they do not cause significant anemia, unlike the hookworms. Trichuris may cause diarrhea, but most infections are asymptomatic.

Trichuris may also cause rectal prolapse in children with heavy infection. Prolapse results from increased peristalsis that occurs in an effort to expel the worms. The whitish worms may be seen on the prolapsed mucosa.

Epidemiology

Whipworm infection occurs worldwide, especially in the tropics; more than 500 million people are affected. In the United States, it occurs mainly in the southern states.

Laboratory Diagnosis

Diagnosis is based on finding the typical eggs (i.e., barrel-shaped [lemon-shaped] with a plug at each end) in the stool (Figures 56–3B and 56–5).

FIGURE 56–5 Trichuris trichiura—egg. Long arrow points to an egg of Trichuris trichiura. Short arrow points to one of the two “plugs” on each end of the egg. (Figure courtesy of Public Dr. M. Melvin, Health Image Library, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.)

Treatment

Mebendazole is the drug of choice.

Prevention

Proper disposal of feces prevents transmission.

ASCARIS

Disease

Ascaris lumbricoides causes ascariasis.

Important Properties

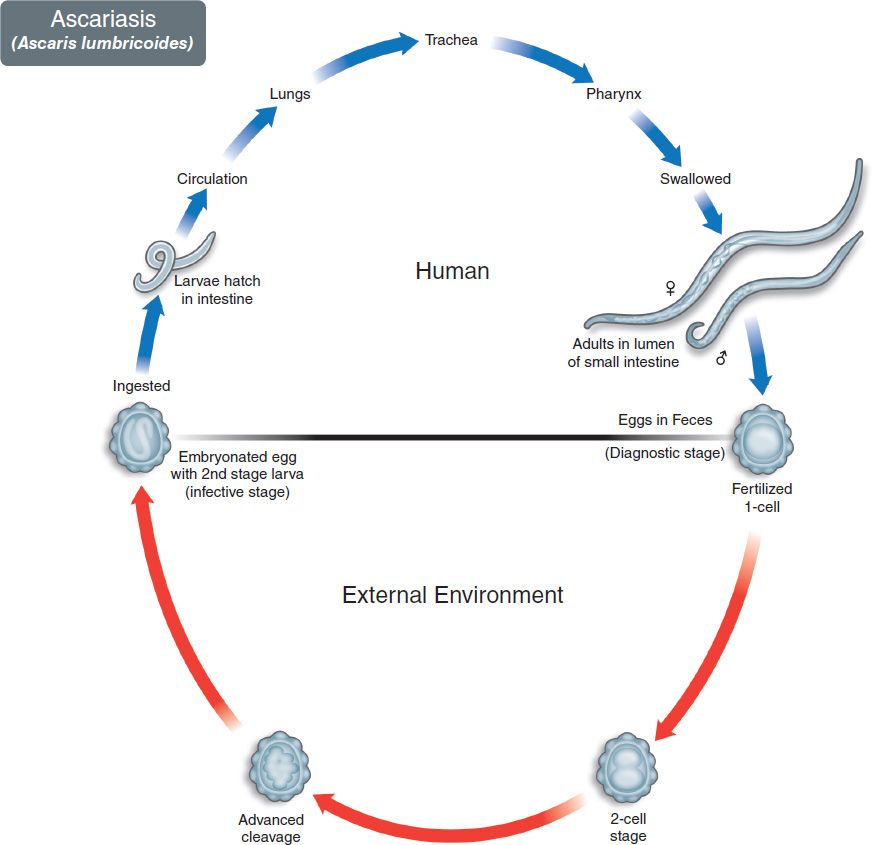

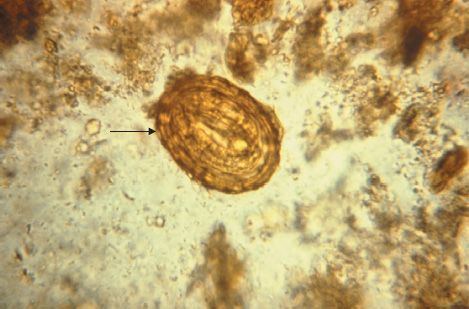

The life cycle of A. lumbricoides is shown in Figure 56–6. Humans are infected by ingesting worm eggs in food or water contaminated with human feces (Figures 56–3C and 56–7). The eggs hatch in the small intestine, and the larvae migrate through the gut wall into the bloodstream and then to the lungs. They enter the alveoli, pass up the bronchi and trachea, and are swallowed. Within the small intestine, they become adults (Figures 56–2C and 56–8). They live in the lumen, do not attach to the wall, and derive their sustenance from ingested food. The adults are the largest intestinal nematodes, often growing to 25 cm or more. A. lumbricoides is known as the “giant roundworm.” Thousands of eggs are laid daily, are passed in the feces, and differentiate into embryonated eggs in warm, moist soil (Figure 56–3C). Ingestion of the embryonated eggs completes the cycle.

FIGURE 56–6 Ascaris lumbricoides. Life cycle. Top: Blue arrow at top left shows eggs being ingested. Larvae emerge in the intestinal tract, enter the bloodstream, and migrate to the lungs. They then enter the alveoli, ascend into the bronchi and trachea, migrate to the pharynx, and are swallowed. Adult Ascaris worms form in small intestine. Eggs pass in human feces. Bottom: Red arrow indicates maturation of eggs in the soil. (Figure courtesy of Public Health Image Library, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.)

FIGURE 56–7 Ascaris lumbricoides—egg. Arrow points to an egg of Ascaris. Note the typical “scalloped” edge of the Ascaris egg. (Figure courtesy of Public Health Image Library, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.)

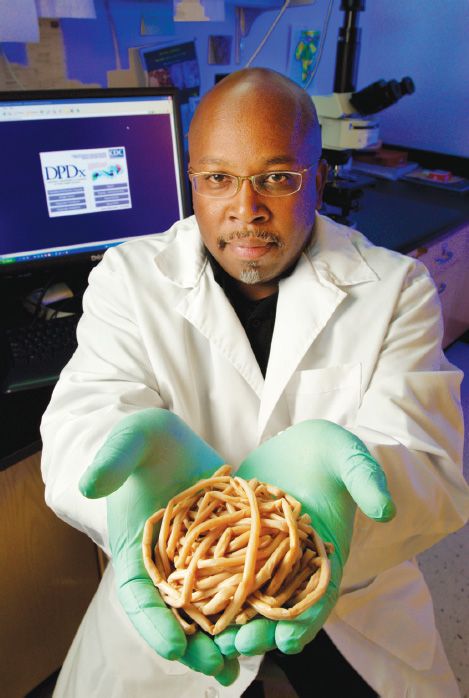

FIGURE 56–8 Ascaris lumbricoides—adult worms. (Figure courtesy of Public Health Image Library, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and Dr. Henry Bishop.)

Pathogenesis & Clinical Findings

The major damage occurs during larval migration rather than from the presence of the adult worm in the intestine. The principal sites of tissue reaction are the lungs, where inflammation with an eosinophilic exudate occurs in response to larval antigens. Because the adults derive their nourishment from ingested food, a heavy worm burden may contribute to malnutrition, especially in children in developing countries.

Most infections are asymptomatic. Ascaris pneumonia with fever, cough, and eosinophilia can occur with a heavy larval burden. Abdominal pain and even obstruction can result from the presence of adult worms in the intestine.

Epidemiology

Ascaris infection is very common, especially in the tropics; hundreds of millions of people are infected. In the United States, most cases occur in the southern states.

Laboratory Diagnosis

Diagnosis is usually made microscopically by detecting eggs in the stools. The egg is oval with an irregular surface (Figures 56–3C and 56–7). Occasionally, the patient sees adult worms in the stools.

Treatment

Both mebendazole and pyrantel pamoate are effective.

Prevention

Proper disposal of feces can prevent ascariasis.

ANCYLOSTOMA & NECATOR

Disease

Ancylostoma duodenale (Old World hookworm) and Necator americanus (New World hookworm) cause hookworm infection.

Important Properties

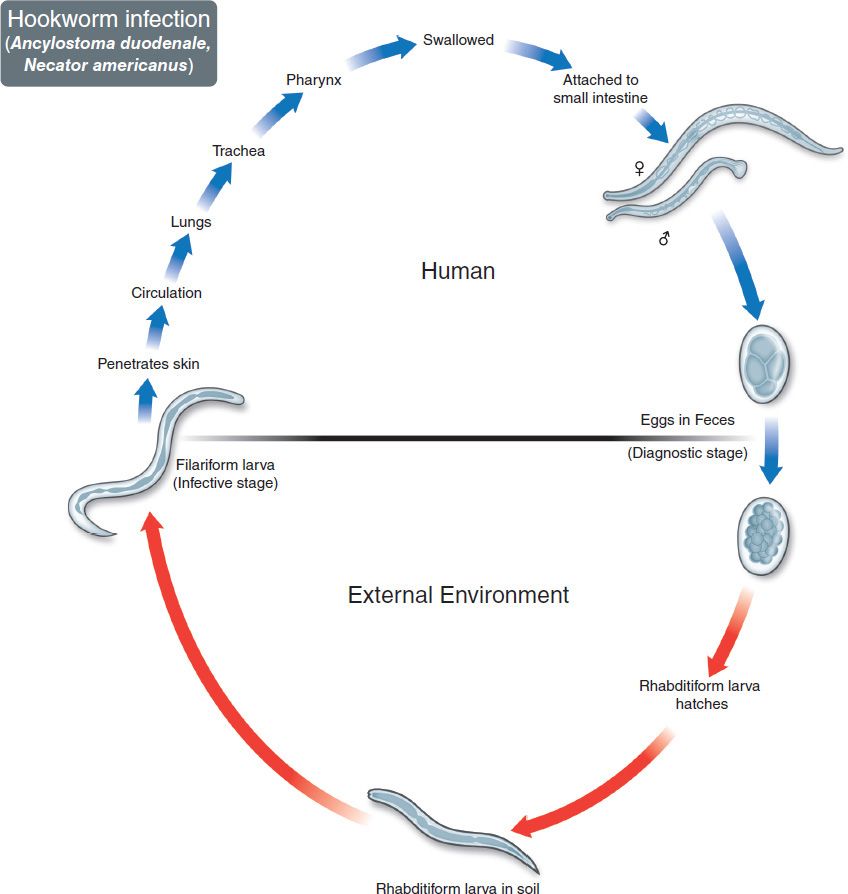

The life cycle of the hookworms is shown in Figure 56–9. Humans are infected when filariform larvae in moist soil penetrate the skin, usually of the feet or legs (Figures 56–2E and 56–10). They are carried by the blood to the lungs, migrate into the alveoli and up the bronchi and trachea, and then are swallowed. They develop into adults in the small intestine, attaching to the wall with either cutting plates (Necator) or teeth (Ancylostoma) (Figures 56–2D, F, and G, and 56–11). They feed on blood from the capillaries of the intestinal villi. Thousands of eggs per day are passed in the feces (Figures 56–3D and 56–12). Eggs develop first into noninfectious, feeding (rhabditiform) larvae and then into third-stage, infectious, nonfeeding (filariform) larvae (Figure 56–2E), which penetrate the skin to complete the cycle.

FIGURE 56–9 Hookworms (Necator and Ancylostoma). Life cycle. Top: Blue arrow on left shows filariform larvae penetrating skin. Larvae migrate through lung and may cause pneumonia. Adult hookworms attach to intestinal mucosa and cause bleeding and anemia. Eggs pass in human feces. Bottom: Red arrow indicates maturation of eggs in the soil to form rhabditiform larvae and then infective filariform larvae. (Figure courtesy of Public Health Image Library, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree