Definition and Classification

Myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) are a group of clonal disorders of hematopoietic stem cells, characterized by dysplastic morphology, cytogenetic aberrations, and—in most cases—cytopenia (

1,

2,

3,

4). MDS typically involves the main hematopoietic lineages: granulocytes, monocytes, erythroid cells, and megakaryocytes. Less often, the morphologic and genetic abnormalities affect other related lineages: mast cells, dendritic cells, and lymphocytes.

Hematopoietic stem cells show increased proliferation while retaining cellular differentiation. One or more cell lines show dysplasia, increased apoptosis, and ineffective hematopoiesis, leading to the coexistence of peripheral cytopenia and bone marrow hypercellularity. The World Health Organization (WHO) 2001 classification and criteria for MDS are given in

Table 20.1, and the WHO 2008 classification without criteria in

Table 20.2 (see

Appendix A for WHO 2008 classification).

In some cases, proliferation outstrips apoptosis, and increased marrow cellularity coexists with increased peripheral cell counts. Such cases are termed myelodysplastic’myeloproliferative neoplasms (MDS’MPN). The WHO 2001 classification and criteria for MDS’MPN are given in

Table 20.3, and the WHO 2008 classification without criteria in

Table 20.4.

The WHO 2008 criteria for MDS and MDS’MPN are not available at the time of writing. Readers are encouraged to consult the WHO 2008 publication for current criteria.

Clinical Course

Myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) occurs predominantly in older adults (median age 70 years), but also in children (5-23). MDS occurs de novo and as a transformation of aplastic anemia, pure red cell aplasia, paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria, and myeloproliferative neoplasms. MDS occurring as a complication of therapy for another neoplastic disease is termed therapy-related or secondary MDS, and is dicussed with acute leukemia in

Chapter 18.

MDS progresses in about 30% of patients to acute leukemia, usually acute myeloid leukemia (AML) but sometimes acute lymphoblastic leukemia. The risk of leukemic transformation depends on age, the number and severity of cytopenias, the extent and degree of dysplasia, the percentage of blasts, cytotoxic drug resistance, number and type of genetic abnormalities, and other factors. Like AML, MDS may undergo spontaneous remission and remission following colony-stimulating factor and immunosuppressive therapy.

Autoimmune disorders occur in more than 10% of patients, owing, at least in part, to clonal lymphoid differentiation and the production of self-reactive CD5’19-positive B cells. These disorders include immune-mediated arthritis and vasculitis, autoimmune cytopenias, Behçet disease, relapsing polychondritis, inflammatory bowel disease, and others. Tuberculosis may be more common in MDS patients.

Acquired hemoglobinopathies and other hematopoietic disorders have been reported in MDS, such as thalassemia, increased hemoglobin F, aplastic anemia, Behçet disease, paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria, and erythropoietic protoporphyria.

Clonal B-cell, T-cell, and plasma cell disorders reported in MDS include chronic lymphocytic leukemia, Hodgkin lymphoma, other malignant lymphomas, clonal gammopathies, multiple myeloma, systemic amyloidosis, T-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma, and other T-cell lymphomas. These neoplasms may be either clonally related or unrelated.

Histiocytic proliferations and disorders reported with chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML) include xanthomas, Langerhans histiocytosis, and nodal histiocytic proliferation. Clonal identity of CMML and histiocytic lesions is possible but unproven.

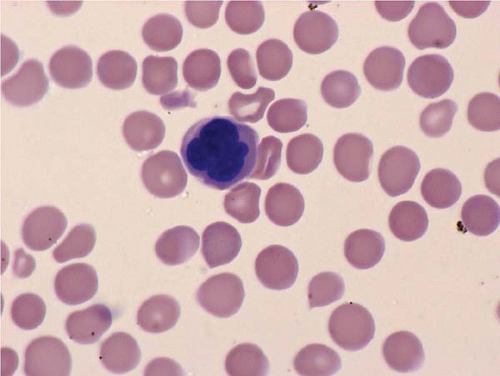

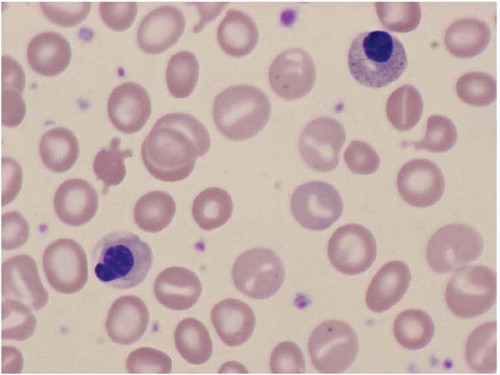

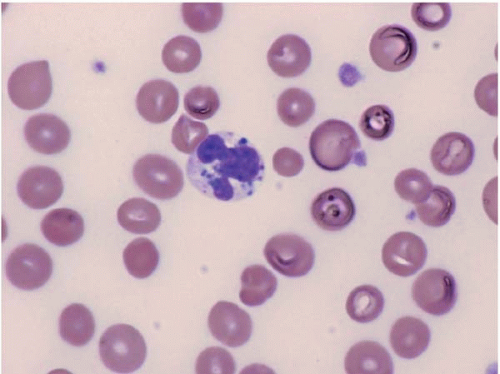

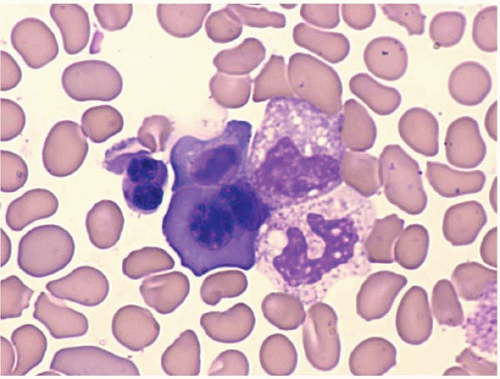

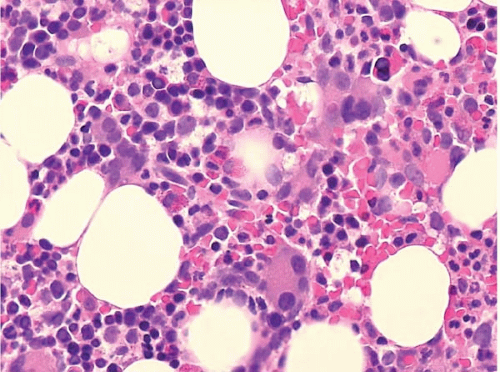

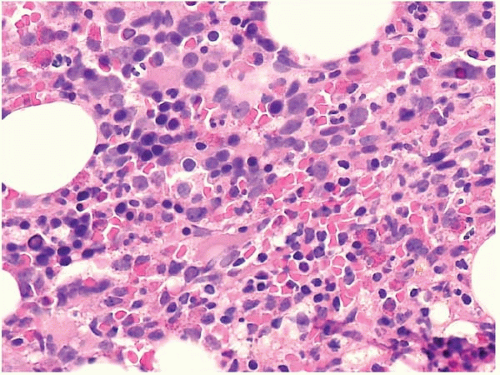

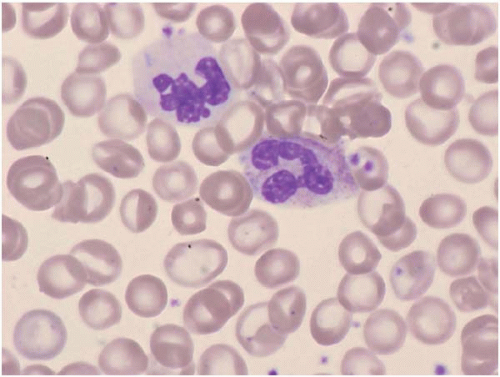

Peripheral Blood and Bone Marrow Findings

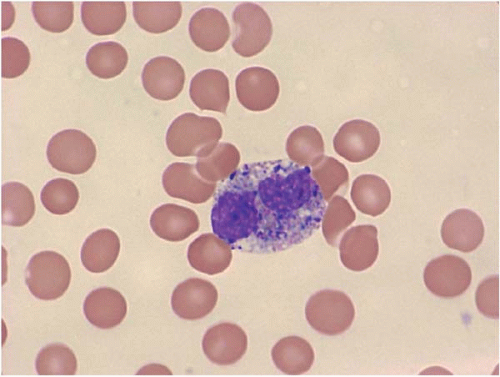

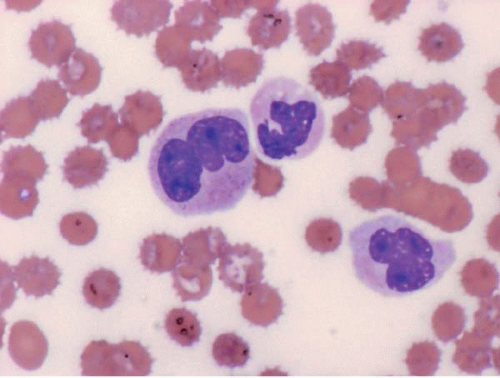

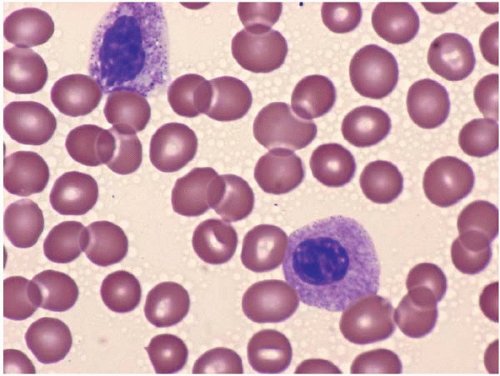

The morphologic hallmark of MDS is myelodysplastic change in hematopoietic cells, affecting one or more cell lines (

Figs. 20.1,

20.2,

20.3,

20.4,

20.5,

20.6,

20.7,

20.8,

20.9,

20.10and

20.11) (

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31). However, dysplastic features may be absent or rare in some cases, especially in MDS with an isolated cytopenia.

Laboratory studies often show macrocytic or normocytic anemia, neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia. Cytopenias may be cyclic. The mean corpuscular hemoglobin contration

is usually normal. The mean corpuscular volume may be macrocytic or normal. The red cell distribution width is often increased. Numerous acquired abnormalities may be found, resembling their constitutional counterparts, such as thalassemia.

Peripheral blood smears usually show abnormal red blood cells (RBC), including subtle variations in size and form. Target cells, teardrop cells, and RBC fragments may be present. Delayed maturation of erythrocytes may cause pseudoreticulocytosis. Other RBC abnormalities include coarse basophilic stippling and Howell-Jolly bodies. Nucleated RBCs may show megaloblastic change and abnormal nuclear contours, consisting of altered shape and lobation.

Dysplastic neutrophils are usually found. These cells may show increased size, abnormal nuclear lobation, and abnormal granularity, usually hypogranularity but occasionally abnormally large granules. Monocytes are less often recognizably dysplastic. They may show abnormal nuclear morphology and immature characteristics.

Platelets usually show no definite morphologic changes. Uncommonly, they may show a smaller size or larger size than normal, or hypogranularity. The large, irregular platelets and megakaryocytic fragments seen in myeloproliferative neoplasms are not usually found.

Bone marrow aspirate smears show variable cellularity. The myeloid:erythroid ratio is also variable, and often decreased. A shift to more immature forms may also be found. Blasts may be increased, but by definition constitute less than 20% of nucleated cells.

Erythroid precursors may show large size, nuclear multilobation, nuclear budding, and other abnormal forms. The cytoplasm may show basophilia, vacuolization, perinuclear rings of dark mitochondria (identified as ringed sideroblasts with iron staining), and coarse or fine periodic acid-Schiffpositive granules.

Granulocytic precursors show dysplastic features, visible as abnormally large size, abnormal nuclear shape and cytoplasmic granularity.

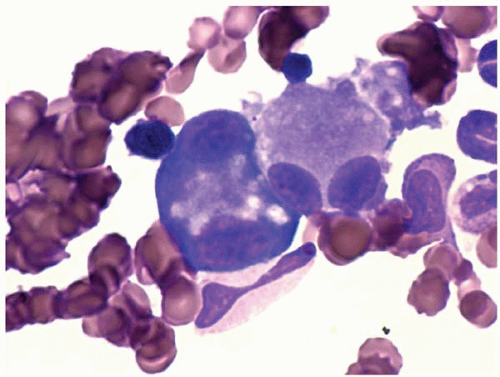

The bone marrow biopsy may show decreased or increased cellularity, depending on the net effect of hematopoietic proliferation, maturation, and intramedullary destruction through apoptosis. Cellularity should be judged by the expected cellularity in healthy subjects of the same age. The normal pattern of erythroid colonies and neutrophil proliferation and maturation is often changed to a disorganized mix of hematopoietic precursors, and blasts, termed ‘atypical localization of immature precursors’. Megakaryocytes may be increased or decreased, and may show smaller size, smaller nuclei with fewer lobes, and separated nuclear lobes.

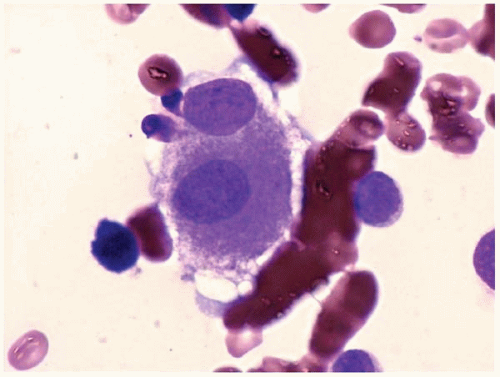

Other bone marrow findings include reactive lymphocytosis and mastocytosis, lymphoid aggregates, fibrosis, increased histiocytes, pseudo-Gaucher histiocytes (

Fig. 20.12), and hemophagocytic syndrome.

The differential diagnosis includes nonclonal myeloplastic syndromes (see

Chapter 16), myeloproliferative neoplasms, and acute myeloid leukemia.