Mycobacterial Infection

Tariq Muzzafar, MBBS

Key Facts

Clinical Issues

High index of suspicion essential for diagnosis

Definitive diagnosis by histology and culture of LN

Molecular methods enable quicker identification of organism

FNA is as useful as excisional LN biopsy in HIV(±) patients

Microscopic Pathology

Granulomas, classically with necrotic center (caseation)

Concentric layers of epithelioid cells, Langhans giant cells, lymphocytes, and plasma cells

Fibrosis, hyalinization, calcification present in healing phase

In LN biopsy specimen, AFB identified by Ziehl-Neelsen, Kinyoun, Fite-Faraco stains

Auramine-rhodamine stain with fluorescent microscopy more sensitive for detection

Top Differential Diagnoses

M. avium-intracellulare lymphadenitis

Histoplasma lymphadenitis

Kikuchi-Fujimoto lymphadenitis

Cat scratch lymphadenitis

Sarcoidosis lymphadenopathy

Reporting Considerations

Suspected or confirmed cases of TB should be reported to local public health department

Identify adult source case and contacts for follow-up

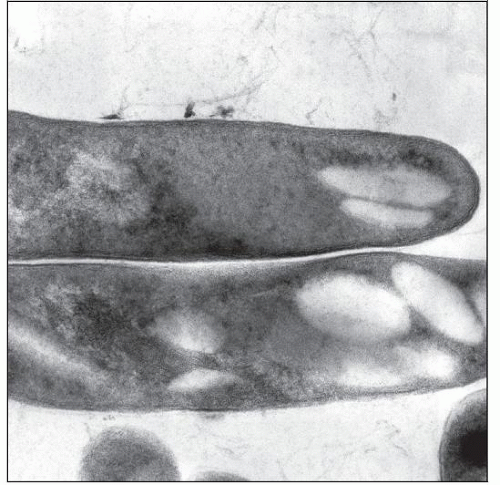

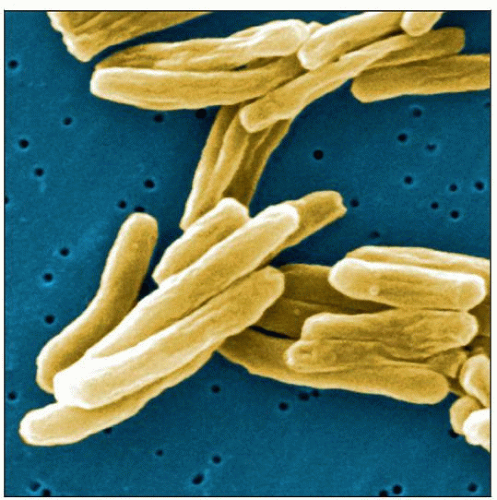

Scanning electron micrograph demonstrates M. tuberculosis; the bacterium ranges from 2-4 µm long and 0.2-0.5 µm wide. (Courtesy J. Carr, CDC Public Health Image Library, #9997. |

TERMINOLOGY

Abbreviations

Acid-fast bacilli (AFB)

Tuberculosis (TB)

Definitions

Lymphadenitis caused by infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis

ETIOLOGY/PATHOGENESIS

Infectious Agents

M. tuberculosis

Immunocompetent Patients

Reactivation of disease at site seeded during primary infection by hematogenous route

As compared to adults, young children more commonly have

Disseminated disease

Severe illness even with low bacterial loads

Deficient immune responses implicated

Infection of tonsils, adenoids, and Waldeyer ring can occur

Abdominal involvement may occur via ingestion of milk or sputum infected with M. tuberculosis

Immunocompromised Patients

Reactivation of latent infection

Part of generalized infection, miliary dissemination

Greater mycobacterial load than immunocompetent patients

Laryngeal involvement very infectious: Special precautions needed

CLINICAL ISSUES

Epidemiology

Incidence

Childhood tuberculosis represents

15-40% of all cases in low- and middle-income countries

2-7% of all cases in industrialized countries

Associated with lower socioeconomic status and overcrowding

Represents ˜ 40% of peripheral lymphadenopathy in developing world

Prevalence of TB lymphadenitis in children ≤ 14 years in rural India: 4.4/1,000

In industrialized countries, most cases occur in immigrants and travelers to endemic areas

Immigrant populations mostly originate from Southeast Asia and Africa

Lymphadenitis is most common form of extrapulmonary tuberculosis

Risk of infection higher in following settings

Lower socioeconomic status, overcrowding leading to close contact with index case

Orphanages and refugee camps

Immunosuppression: HIV (most important), malignancies, chemotherapy, corticosteroids

Age

Incidence

Decreases from birth to 8 years of age

Increases again in late adolescence and early adult life

Gender

M:F = 1:2

Ethnicity

Asian Pacific Islanders more susceptible

Presentation

Characteristically, multiple lymph nodes (LNs) involved

Usually unilateral; can be bilateral

Superficial LN involvement

Most common form of extrapulmonary TB in children

Anterior and posterior cervical (most common)

Supraclavicular, submandibular, preauricular, submental also involved

Classified as nonsevere disease if

No spread to or compression of adjacent neural, vascular, lymphatic, or bony tissues

Isolated sinus or fistula formation from node present, and no involvement of other organs

Inguinal, epitrochlear, axillary involvement rare

Isolated intraabdominal LNs can be involved

Periportal, peripancreatic, and mesenteric

Classified as nonsevere if only enlarged abdominal nodes present

Due to hematogenous or retrograde lymphatic spread from lung, or ingestion of sputum or milk infected with M. tuberculosis

Generalized lymphadenopathy and hepatosplenomegaly may occur

Due to lymphohematogenous spread

Typical course

Lymph nodes usually enlarge gradually in the early stages

Systemic signs and symptoms absent

Low-grade fever may be present

Without treatment, caseation necrosis, rupture of capsule, involvement of adjacent LNs and overlying skin, sinus tract

Occasional cases

Lymphadenitis acute with rapid enlargement

High fever, tenderness, fluctuation, overlying cellulitis

Parabronchial and paratracheal involvement can lead to airway compromise

LN on physical examination

Firm, rubbery, discrete, and nontender; may be matted

Nodes may feel fixed to underlying or overlying tissues

May be swollen and tender due to secondary bacterial infection

Laboratory Tests

Tuberculin skin test (TST)

May be negative with culture documented disease in

10% of immunocompetent children; may become positive subsequently

Disseminated disease

HIV-positive patients

Interferon-Y release assays (IGRA)

Measure in vitro T-cell interferon-Y release in response to 2 unique antigens

Sensitivity similar to TST; specificity higher

Negative in prior Bacillus Calmette-Guérin vaccination and in sensitization to nontuberculous mycobacteria

2 widely studied tests

Enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISpot) (T-SPOT.TB; Oxford Immunotec; Oxford, UK)

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (QuantiFERON-TB Gold; Cellestis; Chadstone, VIC; Australia)

TST and IGRA cannot distinguish between infection, active disease, and past disease

IGRA not recommended to replace TST in low- and middle-income countries

Direct staining

Carbolfuchsin stains (Ziehl-Neelsen stain; Kinyoun stain) highlight AFB

AFB are bright red against blue or green background, depending on counterstain

Must be scanned under oil-immersion

Time consuming due to limited size of field viewed at 1 time

< 2% of children below 10 years positive in newly diagnosed TB

Negative smears do not rule out diagnosis

Fluorochrome stain (auramine O, ± rhodamine)

Scanning is quicker since slides can be scanned at 25x objective

Confirmation may require 40x objective

Bacteria bright yellow (auramine) or orange-red (rhodamine) against dark background

Microbiological culture

General comments

Only ˜ 30% of children confirmed bacteriologically

5% of children < 10 years positive in newly diagnosed TB

Löwenstein-Jensen (LJ) medium

Less sensitive

Recommended only for chromogenic studies and biochemical tests

Middlebrook 7H10 and 7H11 agar medium used for isolation and susceptibility testing

Automated radiometric detection systems: BACTEC 460 (BD Diagnostic Systems; Sparks, MD; USA)

Automated nonradiometric detection systems

MGIT 960 (BD Diagnostic Systems)

MB/BacT System (BioMerieux; Durham, NC; USA)

BACTEC MYCO/F lytic blood culture bottle (BD Diagnostic Systems)

ESP Culture System II (TREK Diagnostic Systems, Inc.; Cleveland, OH; USA)

Gas-liquid and high-performance liquid chromatography

Useful in culture confirmation

Molecular diagnosis (nucleic acid amplification)

Quicker and accurate identification compared to traditional methods; specificity > 97%

Negative result does not rule out diagnosis

AFB microscopy negative cases

Real-time polymerase chain reaction assay useful

Xpert-MTB/RIF (Cepheid, Sunnyvale, California, USA) assay recommended by WHO

Detects 81-bp-core region of RNA-polymerase β-subunit gene flanked by M. tuberculosis-specific DNA sequences

Can test for rifampicin resistance simultaneously

Initial diagnostic test in cases with suspected multidrug-resistant (MDR) TB or HIV-associated TB

AFB microscopy positive cases

Molecular line probe assays preferred

GenoType-MTBDRplus (Hain Lifesciences, Nehren, Germany) assay recommended by WHO

Can test for rifampin and isoniazid resistance simultaneously

Treatment

Surgical approaches

Indications: Failure of antimicrobial chemotherapy, pressure effect

Excisional biopsy preferred since incisional biopsy may result in sinus tract formation

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree