CHAPTER 4 Muscles That Influence the Spine

Second only to the vertebral column and spinal cord, the muscles of the spine are the most important structures of the back. A thorough understanding of the back muscles is fundamental to a comprehensive understanding of the spine and its function. The purpose of this chapter is to discuss the muscles of the back and other muscles that have an indirect influence on the spine. The intercostal muscles provide an example of the latter category. These muscles do not actually attach to the spine, but their action can influence the spine by virtue of their attachment to the ribs. The abdominal wall muscles, diaphragm, hamstrings, and others can be placed into this same category. These muscles have a less direct yet important influence on the spine. Chapter 5 discusses the sternocleidomastoid, scalene, suprahyoid, and infrahyoid muscles.

Although it is beyond the scope of this text to detail the kinesiology of the muscles influencing the spine, a few generalities are in order. There is a complicated interplay of many muscles when a motion of the body, especially of the spine, is produced. Sometimes this is termed muscle coordination. Some of the specifics of this complex interplay are only beginning to be understood, especially in asymmetric motions of the trunk (van Dieen, 1996 Danneels et al., 2001; Andersson et al., 2002). Muscles known as prime movers are the most important. Other muscles, known as synergists, assist the prime movers. For example, the psoas major and rectus abdominis muscles are prime movers of the spine during flexion of the lumbar spine from a supine position, as in the performance of a sit-up. However, the erector spinae muscles also undergo an eccentric contraction toward the end of the sit-up. This contraction of the erector spinae helps to control the motion of the trunk and allows a graceful, safe accomplishment of the movement. The erector spinae muscles are acting as synergists in this instance.

Besides producing motion, muscle contraction also stabilizes the spine by making it stiffer. This is important not only for posture (Cholewicki et al., 1997; Quint et al., 1998), but also for providing a stable base for other motions of the body, such as appendicular motions (Lorimer Moseley et al., 2002).

Muscle coordination seems to be under the control of the central nervous system. The central nervous system is constantly receiving afferent information from the muscles and other surrounding tissues, such as ligaments and tendons. On the basis of this information, the central nervous system appears to use reflex pathways to finely control muscle activity. Some of the details of this process are beginning to be understood (Kang et al., 2002). Interestingly, the specifics of the interplay of the muscles in producing a motion of the body are not always constant. In other words, the same motion may not always be produced by the same muscles working together in the same way. The central nervous system can alter muscle activity depending on the circumstances, such as muscle fatigue, to accomplish the same goal (Clark et al., 2003). This appears to be especially true when there is an abnormality in the system, such as pain or abnormal joint function (McPartland et al., 1997; Hirayama et al., 2001; Lehman et al., 2001; van Dieen et al., 2003).

The muscles of the spine and other muscles associated with the back can, and frequently do, sustain injury. Other painful conditions of muscles (or fascia) are commonly seen by clinicians besides frank injury or pathology of muscles. One of these is myofascial trigger points, sometimes known as myofascial pain syndrome (Travell and Simons, 1983, 1992). Another condition is fibromyalgia or fibromyalgia syndrome (Krsnich-Shriwise, 1997). Both of these conditions are not well understood but are being increasingly accepted as true syndromes. They are similar in presentation but are distinct entities (Schneider, 1995). A complete understanding of the anatomy of the muscles associated with the spine aids in the differential diagnosis of pain arising from muscles versus pain arising from neighboring ligaments or other structures.

SIX LAYERS OF BACK MUSCLES

First Layer

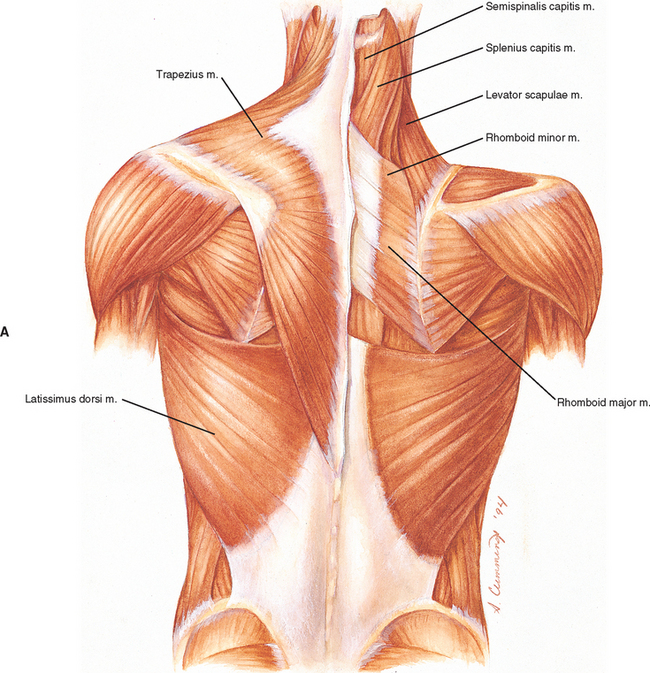

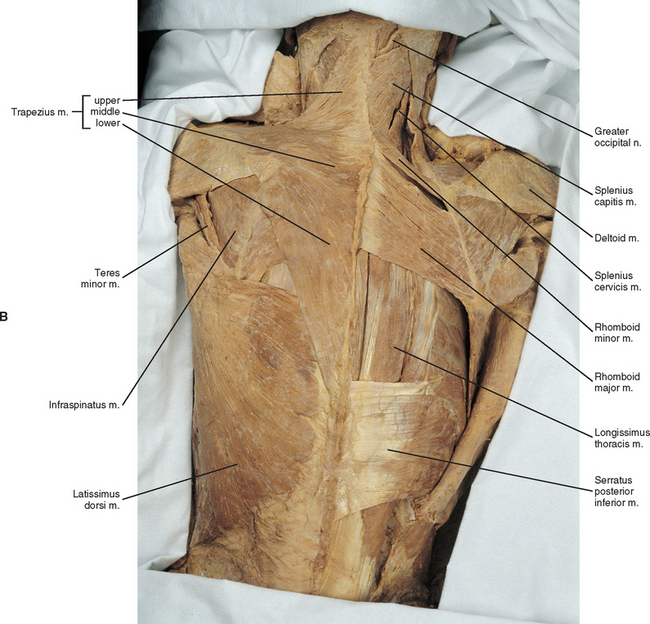

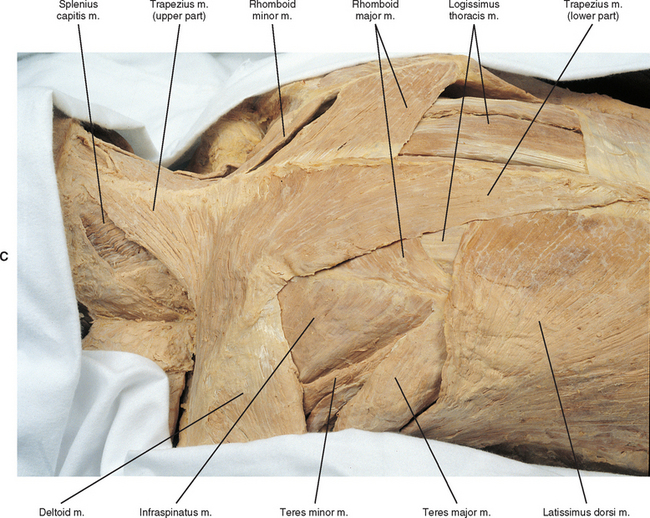

The first layer of back muscles consists of the trapezius and latissimus dorsi muscles (Fig. 4-1). These two muscles course from the spine (and occiput) to either the shoulder girdle (scapula and clavicle) or the humerus, respectively.

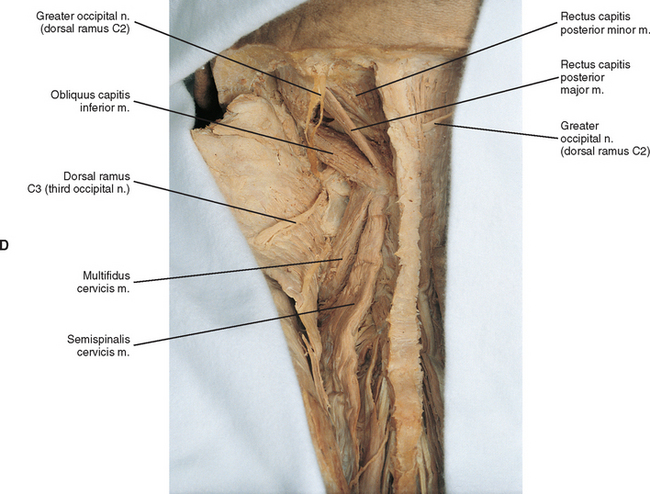

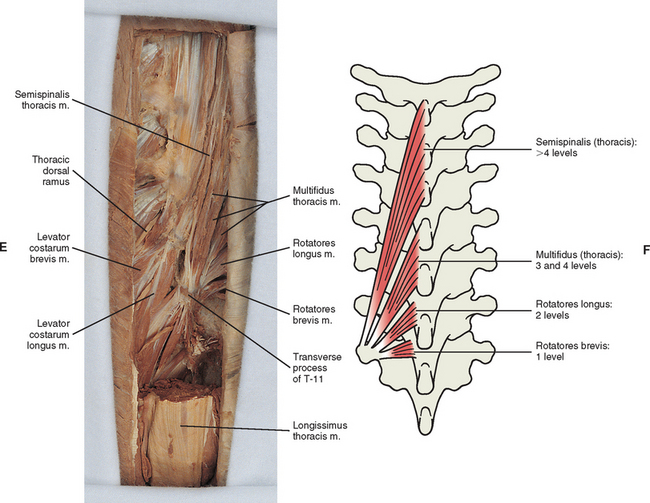

FIG. 4-1 A, First (left) and second (right) layers of back muscles. B, Dissection of these same two layers. C, Close-up, taken from a left posterior oblique perspective. The serratus posterior inferior muscle of the third layer can also be seen in B and in Figure 4-2, A and B.

Trapezius Muscle.

The trapezius muscle is the most superficial and superior back muscle (see Fig. 4-1). It is a large, strong muscle that is innervated by the accessory nerve (cranial nerve XI). In addition to its innervation from the accessory nerve, the trapezius muscle receives some proprioceptive fibers from the third and fourth cervical ventral rami. Because the trapezius muscle is so large, it originates from and inserts on many structures. This muscle originates from the superior nuchal line, external occipital protuberance, ligamentum nuchae of the posterior neck, spinous processes of C7 to T12, and supraspinous ligament between C7 and T12. It inserts onto the spine of the scapula, acromion, and distal third of the clavicle. Detailed morphometric measurements have been performed on this muscle (Kamibayashi and Richmond, 1998).

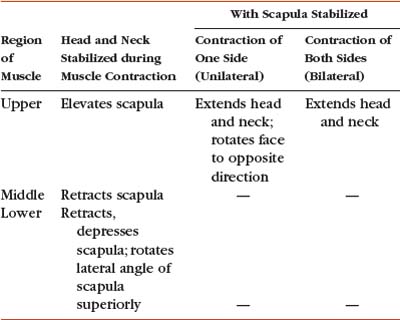

Because of its size and the many locations of its attachments, the trapezius muscle also has many actions. Most of these actions result in movement of the neck and scapula (i.e., the “shoulder girdle” as a whole). The function of the trapezius depends on which region of the muscle is contracting (upper, middle, or lower). The middle portion retracts the scapula, whereas the lower portion depresses the scapula and at the same time rotates the scapula so that its lateral angle moves superiorly (i.e., rotates the point of the shoulder up). The actions of the upper part of the trapezius also depend on whether the head or neck or the scapula is stabilized. When moving the head and neck, the actions of the upper trapezius also are determined by whether the muscle is contracting unilaterally or bilaterally. There is some conflicting evidence as to whether or not the upper fibers of the trapezius muscle help in elevation of the scapula. Based upon information gathered from cadaveric dissections of the attachment points and directions of the upper fibers of the trapezius muscle, Johnson et al. (1994) concluded that these fibers do not aid in elevation of the scapula. On the other hand there is good electromyographic evidence that the upper fibers of the trapezius muscle are active during elevation of the shoulder (Campos et al., 1994; Guazzelli et al., 1994). Table 4-1 summarizes the actions of the trapezius muscle.

Latissimus Dorsi Muscle.

The latissimus dorsi muscle is the most inferior and lateral of the two muscles that make up the first layer of back muscles (see Fig. 4-1). This large muscle has an extensive origin. The origin of the latissimus dorsi includes the following:

The latissimus dorsi is innervated by the thoracodorsal nerve, which is a branch of the posterior cord of the brachial plexus. The thoracodorsal nerve is derived from the anterior primary divisions of the sixth through eighth cervical nerves.

Thoracolumbar (or Lumbodorsal) Fascia.

Because of its clinical significance, the anatomy of the thoracolumbar fascia deserves further discussion. This fascia extends from the thoracic region to the sacrum. It forms a thin covering over the erector spinae muscles in the thoracic region, whereas in the lumbar region the thoracolumbar fascia is strong and is composed of three layers. The posterior layer attaches to the lumbar spinous processes, interspinous ligaments between these processes, and median sacral crest. This layer has its own superficial and deep laminae (Macintosh and Bogduk, 1987a). The middle layer attaches to the tips of the lumbar transverse processes and intertransverse ligaments and extends superiorly from the iliac crest to the twelfth rib. The anterior layer covers the anterior aspect of the quadratus lumborum muscle and attaches to the anterior surfaces of the lumbar transverse processes. Superiorly the anterior layer forms the lateral arcuate ligament (see Diaphragm). The anterior layer continues inferiorly to the ilium and iliolumbar ligament. The posterior and middle layers surround the erector spinae muscles posteriorly and anteriorly, respectively (see Fifth Layer), and meet at the lateral edge of the erector spinae, where these two layers are joined by the anterior layer (Williams et al., 1995). Barker and Briggs (1999) have demonstrated in a cadaveric study that the thoracolumbar fascia may continue more superiorly than classically described. They found that the superficial lamina of the posterior layer ran superiorly to be continuous with the rhomboid muscles, whereas the deep lamina of the posterior layer was continuous superiorly with the splenius muscles. These superior extensions of the fascia were of variable thickness, but seemed thick enough to transmit tension. This means that the thoracolumbar fascia may have a more global influence on biomechanics than thought previously.

Some investigators believe that because the posterior and middle layers surround the erector spinae muscles, injury to these muscles at times may lead to a “compartment” type of syndrome within these two layers of the thoracolumbar fascia (Peck et al., 1986). This syndrome results from edema within the erector spinae muscles. The edema stems from injury and increases the pressure in the relatively closed compartment composed of the erector spinae muscles wrapped within the posterior and middle layers of the thoracolumbar fascia. This may result in increased pain and straightening of the lumbar lordosis (Peck et al., 1986). However, further research is necessary to determine the best approach available to diagnose this condition and the frequency with which it occurs.

Second Layer

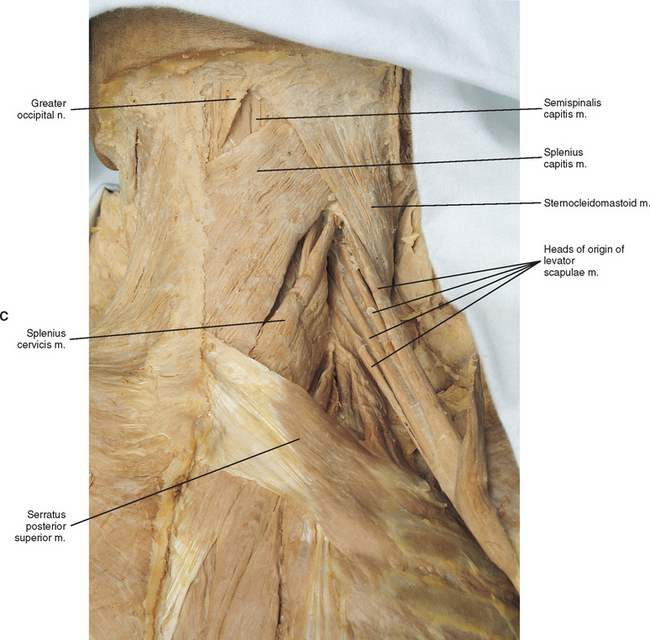

The second layer of back muscles includes three muscles that, along with the first layer, connect the upper limb to the vertebral column. All three muscles lie deep to the trapezius muscle and insert onto the scapula’s medial border. They include the rhomboid major, rhomboid minor, and levator scapulae muscles (see Fig. 4-1). Detailed morphometric measurements have been performed on them (Kamibayashi and Richmond, 1998).

Third Layer

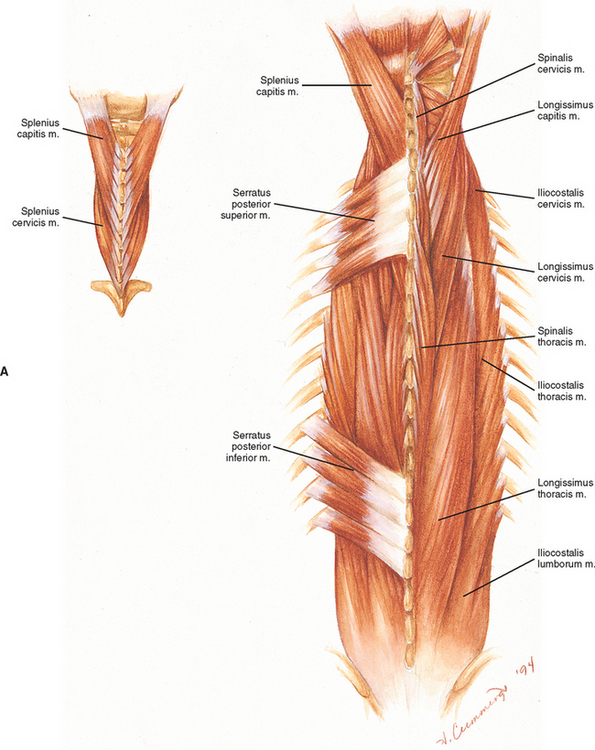

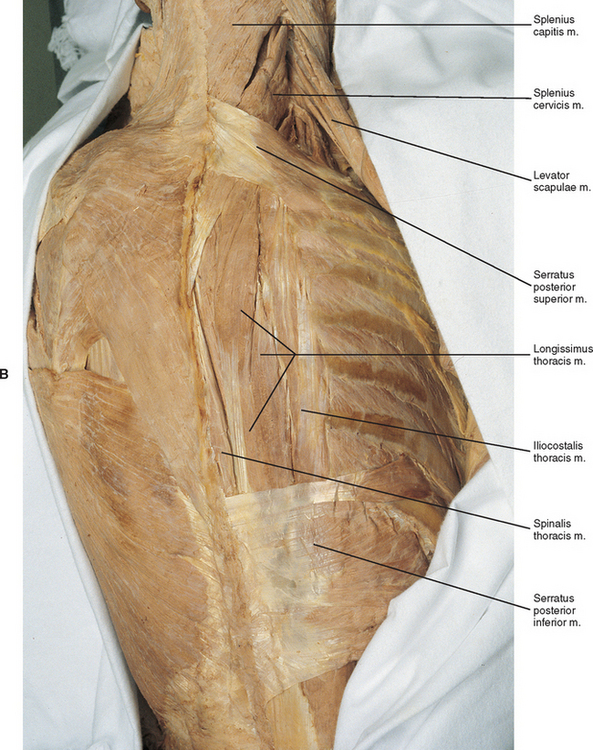

The third layer of back muscles consists of two thin, almost quadrangular muscles: the serratus posterior superior and serratus posterior inferior (Fig. 4-2, A and B).

Serratus Posterior Superior and Serratus Posterior Inferior.

The serratus posterior inferior originates from the spinous processes and intervening supraspinous ligament of T11 to L2. It inserts onto the posterior and inferior surfaces of the lower four ribs and is innervated by the lower three intercostal nerves (T9 to T11) and the subcostal nerve. These nerves are all anterior primary divisions of their respective spinal nerves. The serratus posterior superior and inferior muscles may help with respiration. More specifically, the serratus posterior superior raises the second through fourth ribs, which may aid with inspiration. The serratus posterior inferior lowers the ninth through twelfth ribs, which may help with forced expiration. However, electromyographic evidence refutes a respiratory function for these muscles (Vilensky et al., 2001); they may function primarily in proprioception.

Fourth Layer

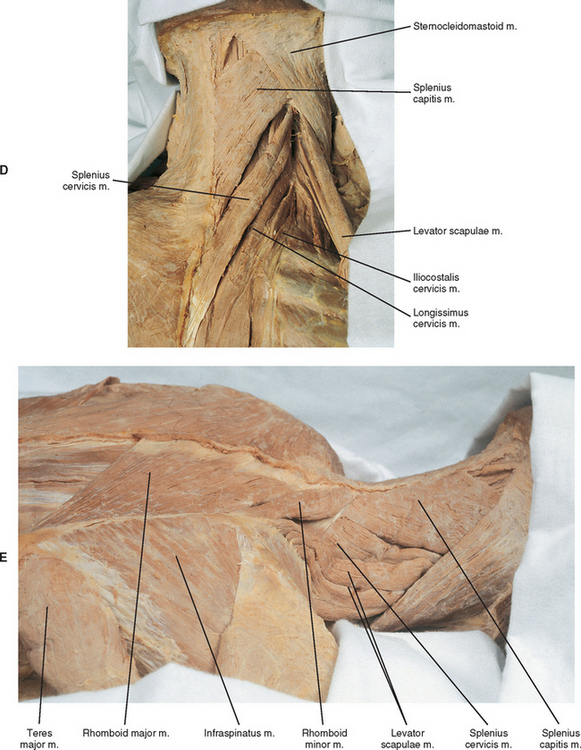

The most superficial layer of deep back muscles is the fourth layer, which consists of two muscles whose fibers ascend in a superolateral direction. This layer is composed of the splenius capitis and splenius cervicis muscles (Fig. 4-2, C to E). Detailed morphometric measurements have been performed on these muscles (Kamibayashi and Richmond, 1998).

Fifth Layer

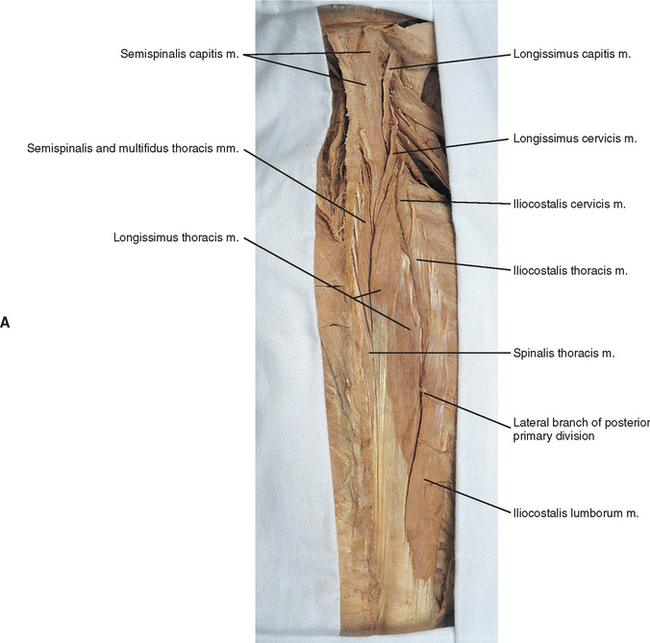

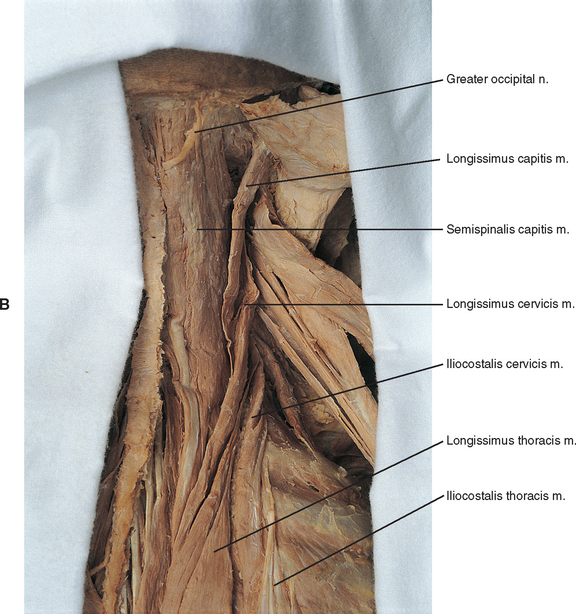

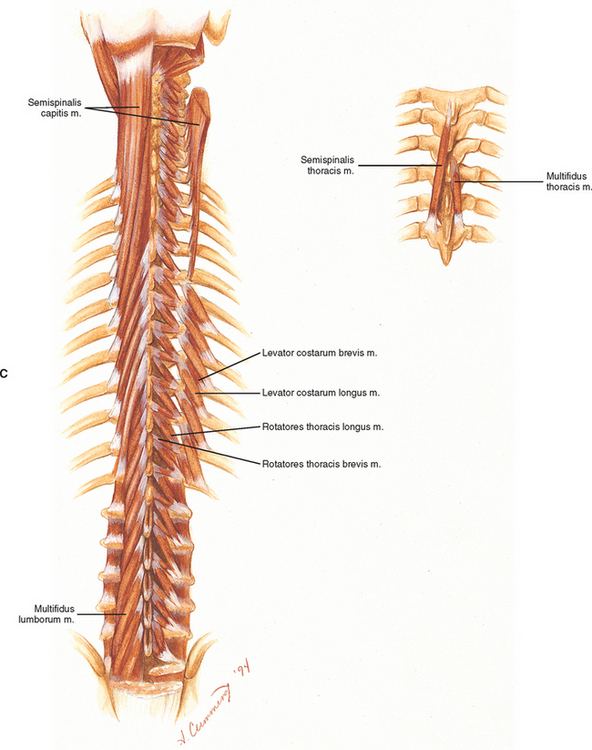

The largest group of back muscles is the fifth layer. This layer is composed of the erector spinae group of muscles (Fig. 4-3, A; see also Fig. 4-2, A and B). This erector spinae group is also collectively known as the sacrospinalis muscle. The muscles that make up this group are a series of longitudinal muscles that course the length of the spine, filling a groove lateral to the spinous processes. Because of this location, these muscles generally have a similar function, which is to extend and laterally flex the spine. The erector spinae are all innervated by lateral branches of the posterior primary divisions (dorsal rami) of the nearby spinal nerves and are covered posteriorly in the thoracic and lumbar regions by the thoracolumbar fascia. These longitudinal muscles can be divided into three groups. These three groups are, from lateral to medial, the iliocostalis, the longissimus, and the spinalis groups of muscles. Each of these groups, in turn, is made up of three subdivisions. The subdivisions are named according to the area of the spine to which they insert (e.g., lumborum, thoracis, cervicis, capitis). The erector spinae muscles are discussed from the most lateral group to the most medial, and each group is discussed from inferior to superior.

Iliocostalis Muscles.

The iliocostalis (iliocostocervicalis) group of muscles is subdivided into lumborum, thoracis, and cervicis muscles (see Fig. 4-3, A and B). Inferiorly the iliocostalis muscles derive from the common origin of the erector spinae muscles.

Iliocostalis lumborum.

Macintosh and Bogduk (1987b) further described the anatomy of the iliocostalis lumborum muscle based on a series of elegant dissections. They found that part of this muscle originates from the posterior superior iliac spine and the posterior aspect of the iliac crest and inserts into the lower eight or nine ribs. They called this part the iliocostalis lumborum pars thoracis. Another part of the classically described iliocostalis lumborum originates from the tips of the lumbar spinous processes and associated middle layer of the thoracolumbar fascia of L1 to L4 (see Thoracolumbar Fascia) and inserts onto the anterior edge of the iliac crest. They called this part the iliocostalis lumborum pars lumborum and found that it formed a considerable mass of muscle. More recent evidence from the Visible Human Project corroborates this classification (Daggfeldt et al., 2000).

Iliocostalis cervicis.

The iliocostalis cervicis originates from the superior aspect of the angle of the third through sixth ribs and inserts onto the posterior tubercles of the transverse processes of the C4 to C6 verte brae. It laterally flexes and extends the lower cervical region and is innervated by the dorsal rami of the upper thoracic and lower cervical spinal nerves.

Longissimus Muscles.

The longissimus muscles are located medial to the iliocostalis group. The longissimus group is made up of thoracis, cervicis, and capitis divisions. The lateral branches of the posterior primary divisions (dorsal rami) of the spinal nerves exit the thorax and then course laterally and posteriorly between the iliocostalis muscles and longissimus thoracis muscle (see Fig. 4-3, A). This fact is used in the gross anatomy laboratory not only to quickly find the lateral branches of the posterior primary divisions, but also to demonstrate the separation between these two large muscle masses. After providing motor and sensory innervation to the sacrospinalis muscle, the lateral branches continue to the skin of the back, providing cutaneous sensory innervation.

Longissimus thoracis.

The longissimus thoracis is the largest of the erector spinae muscles. It arises from the common origin of the erector spinae muscles (see Iliocostalis lumborum). In addition, many fibers originate from the transverse and accessory processes of the lumbar vertebrae. This muscle is the longest muscle of the back, thus the name longissimus. It inserts onto the third through twelfth ribs, between their angles and tubercles. The longissimus thoracis also inserts onto the transverse processes of all 12 thoracic vertebrae. This muscle functions to hold the thoracic and lumbar regions erect, and laterally flexes the spine when it acts unilaterally. It is innervated by lateral branches of the thoracic and lumbar posterior primary divisions.

Macintosh and Bogduk (1987b) found fibers of the longissimus thoracis that are confined to the lumbar and sacral regions. These fibers originated from lumbar accessory and transverse processes and inserted onto the medial surface of the posterior superior iliac spine. The authors called these fibers the longissimus thoracis pars lumborum.

Longissimus capitis.

The longissimus capitis muscle derives from upper thoracic transverse processes (T1 to T5) and articular processes of C4 through C7. It inserts onto the mastoid process of the temporal bone, and its action is to extend the head. If it acts unilaterally, the longissimus capitis can laterally flex the head and rotate it to the same side. It is innervated by the posterior primary divisions of upper thoracic and cervical spinal nerves.

Spinalis Muscles.

Spinalis capitis.

The spinalis capitis muscle differs from the other spinalis muscles in that it does not typically originate from or insert onto spinous processes. This muscle is difficult to differentiate from the more lateral semispinalis capitis muscle (see the following discussion). Its origin is blended with that of the semispinalis capitis from the transverse processes of the C7 to the T6 or T7 vertebra, the articular processes of C4 to C6, and sometimes from the spinous processes of C7 and T1. The fibers of this muscle blend with those of the semispinalis capitis and insert with the latter muscle onto the occiput between the superior and inferior nuchal lines. The spinalis capitis muscle is sometimes called the biventer cervicis muscle because an incomplete tendinous intersection passes across it. When the left and right spinalis capitis muscles contract together, the result is extension of the head. Unilateral contraction results in lateral flexion of the head and neck and also rotation of the head away from the side of contraction. This muscle is innervated by upper thoracic and lower cervical posterior primary divisions.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree