Chapter Thirty. Minor disorders of pregnancy

Maintenance of pregnancy

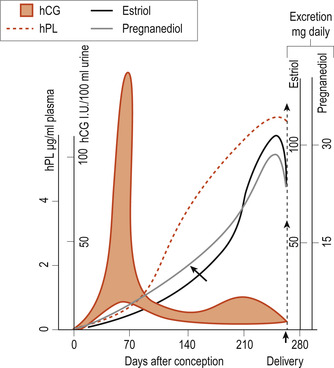

Maternal physiological recognition of pregnancy begins with the presence of the blastocyst in the uterine cavity. The development of the embryo and placentation are described in Chapter 9, Chapter 10, Chapter 11 and Chapter 12. The corpus luteum normally regresses after about 14 days if a fertilised ovum does not reach the uterus. The maintenance of the corpus luteum of pregnancy has been ascribed to the production of human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG) by the cells of the syncytiotrophoblast as they invade the endometrium. This is secreted into maternal blood and taken to the ovary where it augments the action of luteinising hormone from the anterior pituitary gland to continue production of progesterone from the corpus luteum. The role of the corpus luteum is to maintain the pregnancy by secreting steroid hormones, mainly progesterone, until the placenta can take over the major role about 4–5 weeks after the last menstrual period (Johnson 2007). The corpus luteum continues to secrete progesterone but this only plays a minimal role in later pregnancy.

The hormone hCG can be identified in the blood 6–7 days post fertilisation and before the first missed period; its excretion in the urine forms the basis of the widely available and highly efficient immunological pregnancy tests. There is no ovulation, and endocrine production is changed to maintain the pregnancy.

Another mechanism important in maintaining early pregnancy is the suppression of prostaglandin concentrations in decidual tissue. In the menstrual cycle these play a role in luteolysis, the breakdown of the corpus luteum. Prostaglandin concentrations in early pregnancy are lower than those measured in the endometrium during the menstrual cycle. It is possible that prostaglandin production is reduced by a substance which inhibits the biosynthesis of arachidonic acid, their precursor substance. The hormone relaxin, a small polypeptide, seems to be produced by the corpus luteum in early and late pregnancy. It inhibits myometrial activity and may play a role in the maintenance of early pregnancy (Fig. 30.1) (Johnson 2007). Other important factors include inhibin, interferon, cytokines and growth factors which assist in the early development of the conceptus (Coad & Dunstall 2001).

|

| Figure 30.1 Changes in hormone levels during pregnancy. hCG, human chorionic gonadotrophin; hPL, human placental lactogen. (From Hinchliff S M, Montague S E 1990, with permission.) |

Minor disorders of pregnancy

The minor disorders occur because of physiological adaptation of the woman’s body to pregnancy, in particular the effect of progesterone and other hormones on the smooth muscle and connective tissue.

The digestive system

Nausea and vomiting

This troublesome complaint begins early in pregnancy at the 4th week and persists until about the 12th week in most sufferers; a few continue to have symptoms until the 16th week. Although commonly referred to as morning sickness, many women feel nauseous but may not vomit. Others will vomit at any time of day. In a prospective study of 160 women, 80% found nausea lasted all day, and sickness occurred in 1.8% (Lacroix et al 2000). The duration of these symptoms in 90% of women lasted 22 weeks. Nausea and vomiting for approximately two-thirds of women is an expected and normal feature of pregnancy (Flaxman & Sherman 2000, Furneaux & Langley-Evans 2001). A few women will develop severe vomiting known as hyperemesis gravidarum, which is life-threatening to the woman; this is discussed in Chapter 34.

The aetiology of nausea and vomiting is not fully understood. It may be that a combination of physical and emotional factors is involved (Chou et al 2003, Furneaux & Langley-Evans 2001). However, this period of time is close to the peak presence of hCG, which may be a trigger. Oestrogen and progesterone may also be involved. Andersson et al (2004) found an association between depression and increased nausea and vomiting.

Flaxman & Sherman (2000) reviewed the literature and mentioned other facts:

• Peak sickness occurred at 6–18 weeks, the period of embryonic organogenesis—increasing hormone levels.

• Women who experience sickness are less likely to miscarry.

• Aversions to some foods may be protective.

Huxley (2000) suggested that the nausea and vomiting stimulated placental growth by dividing nutrient factors from the mother to the benefit of the growing embryo. Alterations in thyroid function have been suggested as a cause (Mori et al 1988). The severity of morning sickness has been correlated with the increased amount of free thyroxine (T 4), and decreased thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH). There is a link between altered thyroid gland function and nausea and excessive vomiting in pregnancy (Asakura et al 2000).

Perhaps morning sickness is adaptive in an evolutionary sense and nausea and food aversions minimise fetal exposure to toxins during the period of organogenesis. Women are inclined to eat bland food without strong odours and flavours. This avoids the ingestion of spicy plant toxins and foods produced by bacterial and fungal decomposition.

There have been anxieties about the safety of antiemetic drugs. Non-pharmacological measures are best used and are usually sufficient to combat pregnancy nausea. Light snacks instead of large meals and carbohydrate snacks at bedtime and before rising can prevent the hypoglycaemia that appears to be the cause (Lindsay 2004, McParlin et al 2008). The avoidance of iron supplements is advisable. Ginger capsules and ginger root tea have been found to combat nausea and vomiting in some diseases but Marcus et al (2005) warn that the safety of this substance taken in quantity has not been established (Vutyavanich et al 2001). If vomiting persists or becomes severe, a medical practitioner should be consulted. The use of pressure bands has been found to be beneficial to some women (Sook et al 2007, Steele et al 2001).

Heartburn

Heartburn ( reflux oesophagitis) is a burning sensation felt behind the sternum caused by reflux of acid gastric contents into the oesophagus. It is most problematic after 30 weeks of pregnancy, increasing in intensity until term and disappearing after delivery. Some 30–70% of women at some time in their pregnancy complain of heartburn, with 25% of those complaining of symptoms daily in the latter half of pregnancy (Blackburn 2007).

The main cause is the relaxing effect of progesterone on the smooth muscle of the cardiac sphincter between stomach and oesophagus. In the non-pregnant woman, sphincter tone increases in response to raised intragastric pressure to prevent reflux. This ability is greatly diminished in pregnancy as peristaltic activity is slowed and gastric emptying time is lengthened. Pressure from the growing uterus increases the intragastric pressure and flattening of the diaphragm distorts the shape of the stomach and decreases the angle at the gastrojejunal junction (Girling 2000).

The anatomical changes may cause the sphincter to become incompetent, causing a temporary hiatus hernia (Coad & Dunstall 2001). Reflux can be prevented by avoiding bending over when doing housework such as cleaning the bath, particularly with a full stomach. Sleeping in a more upright position by using additional pillows helps at night. A balanced diet, not spicy, with small regular meals, is recommended. Antacids may be taken after meals and at bedtime under medical supervision (Lloyd 2000).

Ptyalism

This disorder, which is more common in women with an Afro-Caribbean background, is excess salivation and is the equivalent of morning sickness. In some cases the woman must continuously wipe saliva from her mouth. It is referred to as ‘spitting’ and is a sign of pregnancy, particularly in the West Indies. If severe, it may lead to loss of fluids and electrolytes and dehydration. Similar advice as for morning sickness may help. It may also accompany heartburn (Girling 2000).

Pica

This is the medical term for the ingestion of non-nutritive substances such as coal, washing starch, soap, toothpaste. There is a belief that the craving occurs because of a need of the fetus for certain minerals but this has not been substantiated by research. Hormones and metabolic changes have also been implicated. In a survey of 10 000 women only 14 respondents had experienced such cravings (Mikkelsen 2007).

Constipation

Constipation is a common and troublesome disorder of pregnancy and may lead to the development of haemorrhoids, which in turn may increase constipation because of a fear of pain. The increased production of progesterone in pregnancy causes relaxation and reduced peristalsis in the smooth muscle of the digestive tract. This increases the transit time of food through the gut and a greater time for water to be absorbed in the large intestine. A dryer bulkier stool is then more difficult to defecate. The gut is also displaced upwards and outwards by the growing uterus. Faulty diet and disregarding the need to defecate add to the problem. In a survey to investigate diet habits and activity in the three trimesters it was found that women who were constipated ate more and drank less water, and physical activity did not seem to affect constipation in this sample (Derbyshire et al 2006).

Oral iron therapy is also implicated by some women. Advice should be given to pregnant women as soon as they have had their pregnancy confirmed to avoid the situation if possible. It is necessary to ensure that they have an adequate fluid intake, maintain regular bowel habits and take in enough roughage in the form of fruits, vegetables and grains. Also live yoghurt is a natural laxative because of its bifidus content. Exercise is also useful. A stool softener or mild laxative can be useful as an adjunct to the above advice (Girling 2000).