17 Methods of Tertiary Prevention

I Disease, Illness, Disability, and Disease Perceptions

Disability and illness obviously derive from the medical disease. However, illness is also powerfully influenced by patients’ perceptions of their disease, its duration and severity, and their expectations for a recovery; together, these beliefs are called illness perceptions. Disease and illness interact; a patient’s illness perceptions strongly predict recovery, loss of work days, adherence, and health care utilization.1,2 To be successful, tertiary prevention and rehabilitation must not only improve patients’ physical functioning, but also influence their illness perceptions. Although there is some evidence of effective psychological interventions on illness perceptions,3 a recent systematic review of interventions of illness perceptions in cardiovascular health found too much heterogeneity among studies to allow for general conclusions.4 Despite the mixed quality of the data, the practicing clinician should consider the patients’ illness perceptions, if only to understand which patients are at high risk of poor outcomes.

III Disability Limitation

A Cardiovascular Disease

1 Risk Factor Modification

Diabetes Mellitus

Type 2 diabetes mellitus increases the risk of repeat MI or restenosis (reblockage) of coronary arteries. Keeping the level of glycosylated hemoglobin (a measure of blood sugar control; e.g., Hb A1c) at less than 7% significantly reduces the effect of diabetes on the heart, kidneys, and eyes. Many authorities advocate treating diabetes as a coronary heart disease equivalent, based on a Finnish study that showed that patients with diabetes (who had not had a heart attack) had a similar risk of MI as patients with established CAD.5 Even though this study’s methods and results are in dispute, the management of diabetes mellitus has shifted. The approach no longer focuses only on sugar control, but instead aims for multifactorial strategy to identify and target patients’ broader cardiovascular risk factors.6 This approach includes treating lipids and controlling blood pressure (BP).

Hypertension

Any hypertension increases the risk of cardiovascular disease, and severe hypertension (systolic BP ≥195 mm Hg) approximately quadruples the risk of cardiovascular disease in middle-aged men.7,8 Effects of hypertension are direct (damage to blood vessels) and indirect (increasing demand on heart). Control of hypertension is crucial at this stage to prevent progression of cardiovascular disease.

Sedentary Lifestyle

It seems that at least 30 minutes of moderate exercise (e.g., fast walking) at least three times per week reduces the risk of cardiovascular disease. There is increasing evidence that sitting itself, independent of the amount of exercise, increases the risk of MI.9 The uncertainty occurs partly because it is difficult to design observational studies that completely avoid the potential bias of self-selection (e.g., people with incipient heart disease may have cues that tell them to avoid exercise). Nevertheless, there is increasing emphasis on the potential benefits of even modest physical activity, which has direct effects on lipids and also helps to keep weight down, which itself improves the blood lipid profile. Conversely, there is a growing appreciation for adverse health effects of “sedentariness.”9

Excess Weight

Weight loss ameliorates some important cardiac risk factors, such as hypertension and insulin resistance. Some studies suggest that alternating dieting and nondieting, called weight cycling, is a risk factor in itself,10 but other studies question this conclusion.11 The most recent findings in this area suggest that weight gain and loss may result in lasting hormonal and cytokine alterations that facilitate regaining weight.12 Although weight cycling may have specific associated risks, whether any such risks are truly independent of obesity itself remains unclear.13–16 At present, expert opinion generally supports a benefit from weight loss, with greater benefit clearly attached to sustainable weight loss17 (http://www.nwcr.ws/). Achieving sustained weight loss remains a considerable challenge (see Chapter 19).

Dyslipidemia

The risk of progression of cardiovascular disease is increased in patients with dyslipidemia (abnormal levels of lipids and the particles that carry them), which can act synergistically with other risk factors (see later and also Chapter 5, especially Table 5-2, and Chapter 19). Disease progression can be slowed by improving blood lipid levels or by addressing other modifiable risk factors (e.g., hypertension, diabetes) that benefit from diet and exercise.

3 Symptomatic Stage Prevention

Behavior Modification

Patients should be questioned about smoking, exercise, and eating habits, all of which affect the risks of cardiovascular disease. Smokers should be encouraged to stop smoking (see Chapter 15 and Box 15-2), and all patients should receive nutrition counseling and information about the types and appropriate levels of exercise to pursue. Hospitalized patients with elevated blood lipids should be placed on a “heart healthy” diet (see Chapter 19) and encouraged to continue this type of diet when they return home. This change in diet requires considerable coaching, often provided by a specialized cardiac rehabilitation nurse, dietitian, or both.

B Dyslipidemia

High-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol

High-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol

Low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol

Low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol

Very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) cholesterol, which is associated with triglycerides (TGs)

Very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) cholesterol, which is associated with triglycerides (TGs)

The TC level is equal to the sum of the HDL, LDL, and VLDL levels:

The “good cholesterol,” HDL, is actually not only cholesterol but rather a particle (known as apoprotein) that contains cholesterol and acts as a scavenger to remove excess cholesterol in the body (also known as reverse cholesterol transport). HDL is predominantly protein, and elevated HDL levels have been associated with decreased cardiovascular risk. LDL, the “bad cholesterol,” is likewise not just cholesterol but a particle that contains it. Elevated LDL levels have been associated with increased cardiovascular risk. A high level of certain LDL particles may be a necessary precursor for atherogenesis (development of fatty arterial plaques). Much of the damage may be caused by oxidative modification of the LDL, making it more atherogenic.12 VLDL, another “bad cholesterol,” is actually a precursor of LDL. The particle is predominantly triglyceride.

1 Assessment

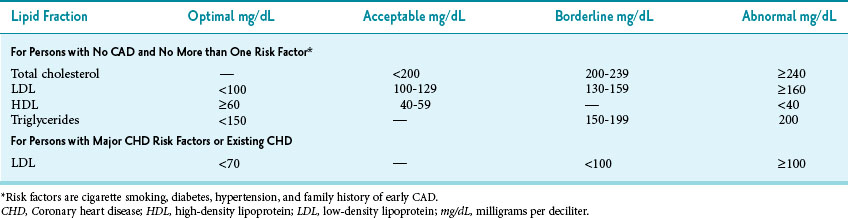

A variety of index measures have been proposed to assess the need for intervention and to monitor the success of preventive measures. The most frequently used guidelines are those of the Third National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP),18 as modified based on more recent research.19 This discussion and Table 17-1 indicate the levels of blood lipids suggested by the widely accepted NCEP recommendations for deciding on treatment and follow-up. New NCEP recommendations are expected in 2012.

Table 17-1 Evaluation of Blood Lipid Levels in Persons without and with Coronary Risk Factors or Coronary Artery Disease (CAD)

Total Cholesterol Level

The TC level may be misleading and is a poor summary measure of the complicated lipoprotein-particle distributions that more accurately define risk. In insulin resistance, for example, TC tends to be normal, but there is an adverse pattern of lipoproteins—high triglycerides and low HDL. This pattern originally was discerned in the Framingham Heart Study and is sometimes referred to as syndrome X. In the Helsinki Heart Study, primary dyslipidemia was defined as the presence of a non-HDL cholesterol level 200 mg/dL or greater on two successive measurements.20 Many clinicians find this index useful because it uses the total contribution of cholesterol fractions currently considered harmful. Some specialists pay attention to the ratio of the TC level to the HDL level, as discussed later.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree