29 Health Care Organization, Policy, and Financing

I Overview

All health care systems strive to reconcile seemingly unlimited health care needs with limited resources. In an ideal world, health care systems would achieve three goals: universal access, high quality, and limited costs. In the real world, there are tradeoffs; at best, health care systems can attain only two of these three goals at any one time1 (Fig. 29-1).

Figure 29-1 The “iron triangle” of health care.

(From Kissick W: Medicine’s dilemmas: infinite need versus finite resources, New Haven, Conn, 1994, Yale University Press.)

A Terminology in Health Policy

Health care policy and financing require the use of economic terminology, including concepts such as needs and demand, utilization, and elasticity, often with an array of acronyms (Box 29-1). The need for health care usually is considered a professional judgment. Although the term “felt need” is sometimes used to describe a patient’s judgment about the need for care, more frequently the demand for health care is actually studied. Demand has a medical and an economic definition. The medical definition of demand is the amount of care people would use if there were no barriers to care. The problem with this definition is that there almost always are barriers to care: cost, convenience, fear, or lack of real availability (see later). The economic definition of demand is the quantity of care that is purchased at a given price. For this economic definition to work, there must be an assumption of price elasticity (i.e., an assumption that as prices increase, the demand for a given service will decrease).

Box 29-1 Frequently Used Acronyms in Health Policy with Descriptions

| ACO | Accountable Care Organization New care model that includes providers and hospitals cooperating together for better outcomes and taking financial risk for outcomes. |

| ADA | Americans with Disabilities Act Forbids discrimination based on disabilities and requires employers to make reasonable accommodations for disabled workers. |

| CAA | Clean Air Act Regulates emissions from area, stationary, and mobile sources. |

| CERCLA | Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act Also called Superfund Act, established a trust fund for cleanup of abandoned and uncontrolled hazardous waste sites. |

| CMS | Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services U.S. federal agency that administers Medicare, Medicaid, and the State Children’s Health Insurance Program. |

| COBRA | Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1985 Allows employees to continue their insurance after job termination. |

| CWA | Clean Water Act Established pollution control for discharges into U.S. waterways; does not address drinking water (see SDWA). |

| EMR | Electronic medical record |

| EMTALA | Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act Law that requires emergency departments to provide initial evaluation and stabilization of all patients regardless of their ability to pay. |

| EPA | Environmental Protection Agency |

| ERISA | Employee Retirement Income Security Act Regulates the content of established employee health plans. |

| FIFRA | Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, & Rodenticide Act Enacted in 1996, controls the distribution, use, and sale of pesticides. |

| FQHC | Federally qualified health centers Community health centers that qualify for special federal grants to treat Medicare and Medicaid patients. |

| HIPAA | Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act Calls for standards in implementing a national health information infrastructure and for regulation of the protection of individual health information in such a system. |

| HSA | Health savings account Individual tax-preferred savings account for health expenses, usually coupled with a high-deductible insurance plan. |

| MCO | Managed care organization |

| PCMH | Patient-centered medical home Care model in which patients are cared for by a physician-directed team that provides comprehensive care with enhanced access and responsibilities for patient engagement, coordination, and population management. |

| PPACA | Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act Health care reform bill passed in 2010 under President Obama in an effort to enact universal health care; Supreme Court ruled it constitutional in 2012. |

| PRO | Peer review organization Also formerly called professional review organization; group of medical professionals or a health care company that contracts with CMS to ensure that services covered by Medicare meet professional standards. |

| RCRA | Resource Conservation and Recovery Act Established that the Environmental Protection Agency should control hazardous waste “from cradle to grave.” |

| SARA | Superfund Amendments and Reauthorization Act Expanded CERCLA and established a community’s right to obtain information about hazards. |

| SDWA | Safe Drinking Water Act Protects surface water and groundwater designated as drinking-water sources. |

| TRI | Toxic Release Inventory Publicly available database on toxic chemical releases and other waste management activities. |

This assumption has been tested in one of the largest social science experiments, the Health Insurance Experiment conducted by the RAND Corporation in the 1970s. In this study, 5809 enrollees were randomly assigned to different insurance plans providing different levels of coverage, deductibles, and copayments. The study found that patients did change their utilization of health care somewhat in response to different insurance levels (i.e., there was some elasticity of health care to price). However, this elasticity was fairly small compared with that of demand for nonmedical goods and services. Furthermore, health care spending was reduced for both necessary care and unnecessary care, which led to worse blood pressure control, vision, and oral health.2 These results call into question the suitability of market-based solutions for health care problems. It also demonstrates how almost any health policy solution usually has negative side effects, called unintended consequences.

B Factors Influencing Need and Demand

One might expect that the unmet need for medical care would be greatest among the poorest members of society, but that is not always true. People with income below some percentage of the poverty line are eligible for Medicaid (see later). People whose incomes are too high to be eligible for Medicaid are those who do not receive medical insurance in their jobs and are not able to pay for individual medical care insurance policies, and who are considered the medically indigent. They may be able to support themselves until a medical catastrophe strikes, but then they are unable to pay their bills. Many of the medically uninsured (those who have no health insurance) and medically underinsured (those whose health insurance is inadequate) are medically indigent. They are not on welfare, but they cannot financially tolerate major medical bills. In 2011 the medically uninsured population in the United States numbered about 49.9 million people, about 17% of the U.S. population.3

C International Comparison

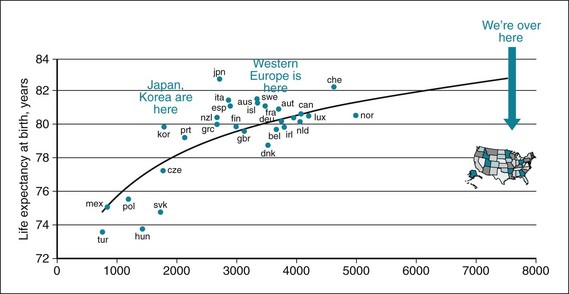

The United States has a higher growth of health care costs than other countries; it spends almost 50% more on health care than other industrialized countries, including Germany, Canada, and France, which provide health insurance to all citizens.4 In 2008 the United States spent 16% of its gross domestic product (GDP) on health care, more than any other country. Sadly, these higher expenditures do not lead to uniformly superior outcomes5 (Fig. 29-2). What is worse, the United States has made much less progress than other industrialized countries in improving overall life expectancy in the past 40 years.6

Figure 29-2 Total expenditure of health against life expectancy by country.

(Modified from http://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2011/04/oecd-us-outspends-average-developed-country-141-in-health-care/237171.)

A study comparing the quality of health care across industrialized countries found that, as in past years, the United States ranks last or next to last on five dimensions of a high-performance health care system: quality, access, efficiency, equity, and healthy lives.7 The mismatch between health expenditures and health and the inexorable rise of health cost are driving a push to control (i.e., reduce) health care spending.

To understand why we pay so much for so little health and how that could change, it is important to understand the underlying laws and functions of the health care system. Laws build the underpinnings of the health system and the complex environment that generates the conditions for health.8

II Legal Framework of Health

A U.s. Public Health System

Government’s public health responsibilities exist at three levels: federal, state/tribe, and local/municipal.8 Local public health agencies can report to a centralized state health department, to local governments, or to both.

The responsibility for public health below federal level is usually scattered through multiple agencies, and each state and locality has its own framework of laws and regulations. Most of the existing legislation was enacted at a time when infectious diseases were the main threat to public health. Frequently, these laws have not been meaningfully updated to account for new threats, such as chronic diseases, bioterrorism, or emerging epidemics, nor has the ability to share data kept pace with technologic innovations8 (see Chapter 26).

For all states, surveillance and required reporting are exercises of state police powers.

B Environmental Laws

The Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) gave the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) control over hazardous waste “from cradle to grave.” It focused only on active and future facilities, not on defunct sites. These inactive sites are addressed through the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA), also called the Superfund Act. This law created a tax on industries and established a trust for cleanup of abandoned and uncontrolled hazardous waste sites. CERCLA was amended in 1986 through the Superfund Amendments and Reauthorization Act (SARA), which established the community’s right to obtain information about hazards and the Toxic Release Inventory (TRI). The Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, & Rodenticide Act (FIFRA), enacted in 1996, controls the distribution, use, and sale of pesticides.9

D Health Care Financing and Insurance

1 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) became law in 2010 and may be the most comprehensive health care legislation since Medicare in 1965. The act offers a mix of regulations covering a wide swath of topics.10 In broad strokes, PPACA does the following:

Requires most U.S. citizens and legal residents to have health insurance (individual mandate), and provides tax penalties if they do not.

Requires most U.S. citizens and legal residents to have health insurance (individual mandate), and provides tax penalties if they do not.

Expands Medicaid, provider payments in Medicaid, and Children’s Health Insurance Program coverage.

Expands Medicaid, provider payments in Medicaid, and Children’s Health Insurance Program coverage.

Provides subsidies to individuals at certain income levels to obtain insurance.

Provides subsidies to individuals at certain income levels to obtain insurance.

Establishes state-based insurance exchanges for employers and individuals to obtain coverage.

Establishes state-based insurance exchanges for employers and individuals to obtain coverage.

Imposes rules on insurance plans, requiring them to provide basic preventive services at no cost and insurance coverage for dependent children up to age 26, and forbidding them to exclude patients because of preexisting conditions (see Chapter 28).

Imposes rules on insurance plans, requiring them to provide basic preventive services at no cost and insurance coverage for dependent children up to age 26, and forbidding them to exclude patients because of preexisting conditions (see Chapter 28).

Provides funds for various initiatives to explore innovative care approaches, such as accountable care organizations, comparative effectiveness research, and other attempts to reduce health care costs without jeopardizing quality.

Provides funds for various initiatives to explore innovative care approaches, such as accountable care organizations, comparative effectiveness research, and other attempts to reduce health care costs without jeopardizing quality.

Establishes an Independent Payment Advisory Board to provide recommendations to reduce Medicare costs; these recommendations become binding unless Congress finds similar cost reductions elsewhere.

Establishes an Independent Payment Advisory Board to provide recommendations to reduce Medicare costs; these recommendations become binding unless Congress finds similar cost reductions elsewhere.

Decreases expenses by penalizing readmissions, taxing high-end plans, cutting provider payments, and establishing a value-based purchasing program that penalizes hospitals for low rates on established quality metrics.

Decreases expenses by penalizing readmissions, taxing high-end plans, cutting provider payments, and establishing a value-based purchasing program that penalizes hospitals for low rates on established quality metrics.

Increases funds for employer-based wellness programs and preventive services with an A or B rating from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF).

Increases funds for employer-based wellness programs and preventive services with an A or B rating from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF).

The PPACA closely mirrors the health reform law passed in Massachusetts in the early 2000s. Not surprisingly, given the political stakes, opinions differ about what the Massachusetts experience has shown. Most analysts agree that the health care reform has expanded the insured pool and increased access to providers, perhaps more so for disadvantaged citizens.11 Views on the impact on costs are more mixed. The reform has resulted in a net cost rather than net savings and has led to an influx of more newly insured patients without expanding the provider pool, which may have increased wait times. Also, the reform has not changed patient behavior or convincingly slowed the growth of health care costs in Massachusetts.12 In June 2012 the U.S. Supreme Court ruled on the balance of federal and state powers in regards to health care, and the extent of federal powers under the commerce clause to enforce the individual mandate (see Chapter 25). The Court held that the individual mandate exceeded Congress’ power to regulate commerce, but was constitutional under the power to levy taxes.13

III the Medical Care System

B Levels of Medical Care

In an effort to maximize the effectiveness and efficiency of the process, health care professionals have proposed an integrated system of graded levels of care. The levels range from treatment in the patient’s home, the least complex level, to treatment in a tertiary medical center, the most complex level of care (Box 29-2). A patient is initially assigned to an appropriate level of care and is reassigned to another level whenever there is an improvement or setback in the patient’s condition. Although the movement from one level to another should be easy, rapid, and smooth, often this is not the case. Transitions in care are risky, and transfers require particular care to accurate communication of medication changes, treatment plans, and follow-up tests.