Metastases in the Breast from Nonmammary Neoplasms

SYED A. HODA

In 1936, Dawson1 described a 25-year-old woman who had diffuse lymphatic channel involvement in both breasts from gastric signet ring cell adenocarcinoma. Her review of the literature revealed four patients with breast metastases from gastric carcinoma and two from ovarian carcinoma. All patients had generalized metastases, as did three women with breast metastases from uterine cervical carcinoma reported in 19472 and 1948.3 A 43-year-old woman with metastatic intestinal carcinoid in the breast documented in 1952 presented with carcinoid syndrome, an enlarged liver, and multiple metastatic nodules in both breasts.4 Autopsy disclosed a malignant ileal carcinoid.

Ten more patients with metastases in the breast were described by Charache5 in 1953. This series included two men with malignant melanoma and individual men with carcinomas of the prostate gland and kidney. The man with prostatic carcinoma presented with a breast mass, and the primary site was not detected until autopsy. This is probably the first reported case of an occult nonmammary neoplasm presenting as a metastatic tumor in the breast in the absence of coincidental systemic metastases. Included in the article were two women who had metastatic ovarian carcinoma in the breast, and there were single instances of metastases of malignant melanoma, renal carcinoma, and carcinoma of the thyroid gland and endometrium. One of the patients with ovarian carcinoma developed a solitary breast mass 4 years after treatment of the ovarian primary.

A series of patients reported by Sandison6 in 1959 included four women whose breast tumors were the initial manifestation of occult nonmammary neoplasms. The primary lesions were myeloid sarcoma, small cell carcinoma of the lung, and carcinomas of the stomach and kidney. Subsequent systemic metastases and a rapidly fatal course were described in the four cases. Also included in Sandison’s report were patients who had breast involvement as part of systemic spread of the following neoplasms: malignant melanoma, lymphoma, leiomyosarcoma, and cutaneous squamous carcinoma.

Numerous publications, including those describing case series and individual case reports, of mammary metastases continue to appear regularly.7,8,9 These reports have described a wide variety of primary sites that gave rise to metastatic carcinoma in the breast. In one large series covering cases from 1907 to 1999, metastatic nonmammary malignant neoplasms in the breast represented 3% of malignant breast tumors, with one-third derived from occult extramammary primary lesions.7 However, the 60 cases listed as metastases in the breast included 32 instances (52%) of mammary involvement by lymphoma or leukemia. Williams et al.10 studied 169 patients with metastatic breast involvement by nonmammary “solid organ primary tumors” recorded at the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center between 1983 and 1998. One hundred and forty-nine patients (88.2%) had a history of a previously treated primary tumor, and the primary was occult in 20 (11.8%). The breast lesion was a solitary metastasis in 68 (46.1%) cases. Cutaneous melanoma and pulmonary and gynecologic carcinomas accounted for 78.1% of the primary tumors.

Malignant lymphoma in the breast may be regarded as either a primary breast neoplasm or as part of a systemic lymphoproliferative disease. The inclusion of lymphomas from this category influences statistics on the frequency of metastases in the breast. Malignant lymphoma in the breast is discussed in Chapter 40.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

It is important to consider metastatic tumor in the differential diagnosis when faced with any breast lesion that has unusual clinical, radiologic, gross, or microscopic features. This concern applies to routine biopsy and cytology specimens11 and to mammography.8,12 The pathologist, cytologist, or radiologist does not always have information about previously treated malignant tumors. Alternatively, the primary lesion may be a new, occult neoplasm. The preoperative clinical work-up of an apparently healthy patient with a breast mass is often perfunctory and unlikely to exclude an occult extramammary primary.

Radiographically, metastatic lesions are more often discrete, round shadows without spiculation than being stellate tumors.8,12,13 They are usually not distinguishable from circumscribed primary breast carcinomas, which may be of the papillary, medullary, or colloid type (Fig. 34.1). Microcalcifications are uncommon but have been described in

metastatic ovarian carcinoma13,14,15,16 and in metastatic medullary thyroid carcinoma.17 Metastatic foci are usually solitary initially, but they may become multiple and bilateral with progression of the patient’s clinical course. In one case, metastatic renal carcinoma was detected as a solitary nodule in the breast 15 years after treatment of the primary tumor.18 Squamous carcinoma of the uterine cervix metastatic to the breast studied by ultrasound appeared to be a solid tumor with hypoechoic areas.19 In adolescent girls, metastatic rhabdomyosarcoma appeared as “heterogeneous nodules that were quite different from the usual benign lesions,” although no consistent sonographic pattern was observed.20 A study of various tumors in the breast including metastatic lesions and lymphoma led the authors to conclude that the “gray-scale” sonographic features of nonmammary malignancies of the breast are a hypoechoic mass with indistinct and occasionally irregular margins, frequently without a posterior acoustic phenomenon.21 Breast metastasis of medullary carcinoma of thyroid detected by F-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) has been reported.22

metastatic ovarian carcinoma13,14,15,16 and in metastatic medullary thyroid carcinoma.17 Metastatic foci are usually solitary initially, but they may become multiple and bilateral with progression of the patient’s clinical course. In one case, metastatic renal carcinoma was detected as a solitary nodule in the breast 15 years after treatment of the primary tumor.18 Squamous carcinoma of the uterine cervix metastatic to the breast studied by ultrasound appeared to be a solid tumor with hypoechoic areas.19 In adolescent girls, metastatic rhabdomyosarcoma appeared as “heterogeneous nodules that were quite different from the usual benign lesions,” although no consistent sonographic pattern was observed.20 A study of various tumors in the breast including metastatic lesions and lymphoma led the authors to conclude that the “gray-scale” sonographic features of nonmammary malignancies of the breast are a hypoechoic mass with indistinct and occasionally irregular margins, frequently without a posterior acoustic phenomenon.21 Breast metastasis of medullary carcinoma of thyroid detected by F-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) has been reported.22

Some clinical features are helpful in recognizing that a neoplasm in the breast is a metastatic tumor. The average interval to the development of a mammary metastasis is approximately 2 years for patients with previously treated cancer. Usually, there will already be metastases at other sites, or the metastases in the breast and other sites are detected coincidentally. Isolated initial metastases limited to the breast are uncommon.23 However, when it occurs, metastatic tumor in the breast is at first a single lesion in about 85% of cases.8 A minority of patients have multiple (10%) or diffuse (5%) involvement initially. With progression, multiple breast metastases may become evident, and bilateral breast metastases are eventually found in about 25% of patients. Metastases have been described in ipsilateral axillary lymph nodes (ALNs) in 25% to 48% of patients.8 The frequency of ALN involvement tends to be higher in series that include malignant lymphomas. In patients with metastatic carcinoma or melanoma in the breast, involvement of the ipsilateral ALNs is generally a manifestation of systemic spread, and it is not unusual to also find metastatic tumor in the supraclavicular lymph nodes and at other sites, including the contralateral axilla.

A breast lesion is the initial manifestation of a nonmammary malignant neoplasm in 25% to 35% of patients who have metastatic tumor in the breast.24 The primary tumor is usually a melanoma or carcinoma. One of the most common sites is the lungs, including a surprising number of small cell carcinomas.25

Other sites of occult, clinically inapparent neoplasms that have presented with metastases in the breast include the kidneys,6,7,26,27 stomach,1,6 intestinal carcinoid tumor,28,29,30,31,32 ovarian carcinoma,33,34,35,36 uterine cervix,19 and thyroid gland.37 Occult alveolar soft part sarcoma has also presented as a breast metastasis.38 In an exceptional case, metastatic carcinoma in the breast was the first evidence of an occult renal primary in a woman who previously had mammary carcinoma in the ipsilateral breast treated by breast-conserving surgery.26

Previously diagnosed tumors that have given rise to metastases in the breast, sometimes rather late in the clinical course of disease, include melanoma8,11,39 and sarcomas,6,10,39,40,41 in addition to various carcinomas such as urothelial carcinoma of the bladder42 and carcinomas of the lung39,43 and ovary.13 An uncommon cause of metastatic tumor in the postpartum breast is choriocarcinoma.44,45

MICROSCOPIC PATHOLOGY

An unusual histologic pattern and clinical information about a prior neoplasm are the best clues for identifying a metastatic nonmammary tumor in the breast. It is important to be sensitive to morphologic patterns that are not typical for breast carcinoma. Certain histologic patterns present especially difficult problems because tumors of similar or identical appearance arise in the breast as well as in other organs. Included in this group are squamous, mucinous, mucoepidermoid, and clear cell carcinomas, as well as spindle cell lesions such as malignant melanoma, renal carcinoma, sarcomatoid carcinoma,46 and sarcomas.

When metastatic tumor is a consideration, a search should be made for in situ carcinoma to establish origin in the breast. Since in situ carcinoma cannot be found in all primary mammary carcinomas, this information is only definitive when in situ carcinoma is present. Absence of in situ carcinoma is not a conclusive evidence that a lesion is metastatic.

Metastatic tumor often surrounds and displaces normalappearing breast parenchyma, which typically shows little or no hyperplasia. A peripheral lymphocytic infiltrate and stromal reaction are not unusual at the site of metastatic tumor in the breast as well as primary breast carcinomas. The finding of more than two grossly evident tumor nodules should lead one to consider metastatic tumor, especially if the histologic pattern is unusual. Lymphatic tumor emboli may result from metastases in the breast, as well as from primary breast carcinomas. Diffuse lymphatic spread of metastatic tumor within the breast can occur, rarely producing the clinical appearance of inflammatory carcinoma.47

The distinction between a primary breast tumor and a metastasis in the breast is critical for treatment. Some types of metastatic tumor in the breast can be accurately diagnosed by needle aspiration cytology or needle core biopsy, if the patient has a previously diagnosed nonmammary malignant neoplasm.39,45,48,49 In some cases, excisional biopsy may be necessary to obtain an adequate sample for a complete immunohisto chemical work-up.

Melanoma

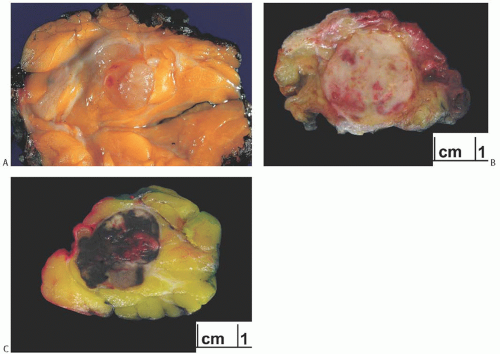

Metastatic melanoma presenting clinically as a breast tumor may be difficult to recognize if the primary lesion is occult, if the pathologist is not informed that the patient received prior treatment for such a lesion, or if the primary site is clinically occult45,50 (Figs. 34.2, 34.3, 34.4 to 34.5). Ravdel et al.23 reviewed 27 patients with metastatic melanoma in the breast recorded in a single institution database. All patients were women, and all had a history of primary cutaneous malignant melanoma. Seventy percent were premenopausal. The majority (82.6%) of primary skin lesions were on the upper body. Melanoma was the most common metastatic neoplasm in the breast in a series of 169 cases of mammary metastases diagnosed at M.D. Anderson Cancer Center from 1983 to 1998.10 Primary malignant melanoma arising in the breast is usually a form of metaplastic carcinoma, and these tumors may display focal reactivity for cytokeratin (CK) (see Chapter 42).

Melanoma can assume multiple histologic appearances and may not produce melanin. Consequently, it should be considered in the differential diagnosis of poorly differentiated carcinoma in the breast. Immunohistochemical studies are usually helpful in establishing the diagnosis. S-100 is a sensitive, but not specific, marker for melanoma. A103, HMB45, MART1 (melan-A), microphthalmia transcription factor (MITF), and tyrosinase are less sensitive, but more specific markers for melanoma.51 A commercial cocktail preparation utilizing a combination of HMB45, MART1, and tyrosinase is useful in this respect.

Pulmonary Carcinoma and Mesothelioma

Carcinoma of the lung has diverse histologic appearances, some of which may resemble mammary carcinoma (Fig. 34.6). Papillary carcinoma of the lung can produce cystic papillary metastases, which mimic primary papillary carcinoma of the breast. Knowledge that carcinoma of the lung was previously diagnosed, or is currently present, and comparative review with histologic sections of the lung tumor are vital aides in this circumstance.

Immunostaining for the thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF-1) is positive virtually in all pulmonary carcinomas and rarely in mammary carcinoma. Robens et al.52 reported TTF-1 immunoexpression in 13 of 546 (2.4%) breast carcinomas, a result that emphasizes the need to employ a battery of markers, and the danger of relying on any one marker in such settings. Napsin A, a functional aspartic proteinase, is a sensitive marker for pulmonary adenocarcinoma that is useful in this setting.53

An exceedingly rare source of metastatic tumor in the breast is epithelioid mesothelioma. Immunoreactivity for D2-40, podoplanin, and calretinin strongly favors mesothelioma over carcinoma.54

Carcinoid Tumors

Carcinoid tumors, particularly those originating in the small intestine, are a surprisingly frequent source of breast metastases and can mimic primary breast carcinoma.55 In some

of these cases, the breast metastasis was the first clinical finding.29,32,56,57,58 In other instances, the breast metastasis occurred in patients who had a known carcinoid tumor and/ or carcinoid syndrome.4,29,32,56,59 The cytologic diagnosis of metastatic carcinoid in the breast by fine-needle aspiration (FNA) has been reported in a woman previously treated for an ileal carcinoid.60 Without knowledge of an extramammary primary, metastatic carcinoid tumor in the breast is easily mistaken for a primary mammary tumor with neuroendocrine differentiation29,56 (Fig. 34.7). Perry et al.55 reviewed 18 cases of metastatic carcinoid involving the breast recorded by two hospitals over a 15-year period. Eleven (62%) of the metastases were derived from the gastrointestinal tract, five from the lungs, and two from unknown sites. All of the gastrointestinal carcinoids were immunoreactive for CDX2, a marker associated with intestinal neoplasms, and CK20. Three of the five (60%) metastatic pulmonary carcinoids expressed TTF-1. Thus, expression of CDX2 and CK20 favors origin in the gastrointestinal tract, whereas the presence of TTF-1

of these cases, the breast metastasis was the first clinical finding.29,32,56,57,58 In other instances, the breast metastasis occurred in patients who had a known carcinoid tumor and/ or carcinoid syndrome.4,29,32,56,59 The cytologic diagnosis of metastatic carcinoid in the breast by fine-needle aspiration (FNA) has been reported in a woman previously treated for an ileal carcinoid.60 Without knowledge of an extramammary primary, metastatic carcinoid tumor in the breast is easily mistaken for a primary mammary tumor with neuroendocrine differentiation29,56 (Fig. 34.7). Perry et al.55 reviewed 18 cases of metastatic carcinoid involving the breast recorded by two hospitals over a 15-year period. Eleven (62%) of the metastases were derived from the gastrointestinal tract, five from the lungs, and two from unknown sites. All of the gastrointestinal carcinoids were immunoreactive for CDX2, a marker associated with intestinal neoplasms, and CK20. Three of the five (60%) metastatic pulmonary carcinoids expressed TTF-1. Thus, expression of CDX2 and CK20 favors origin in the gastrointestinal tract, whereas the presence of TTF-1

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree