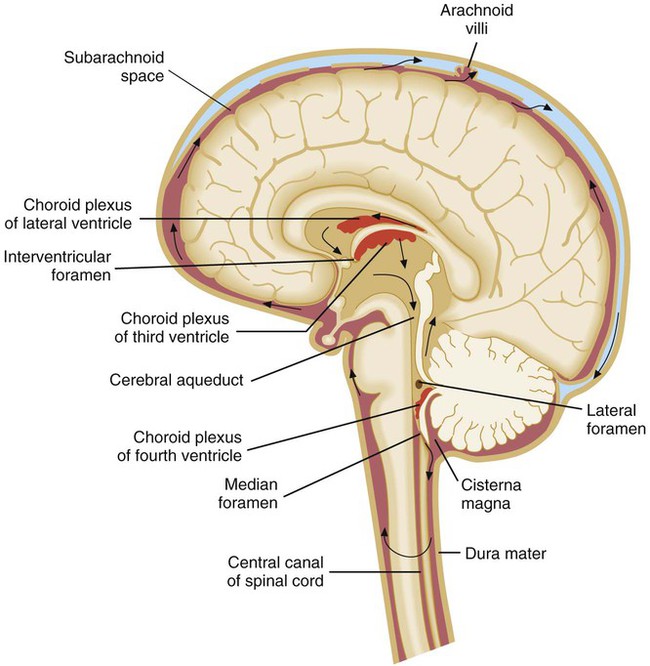

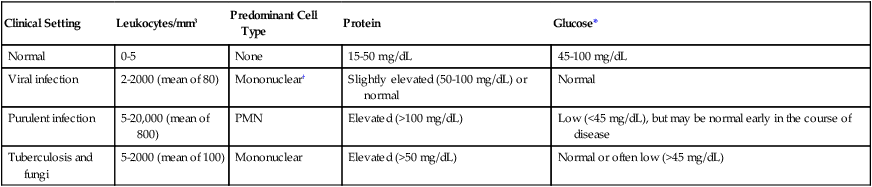

1. Describe the anatomy of the central nervous system (CNS), and list the anatomic structures that compose it. 2. Define meninges; name the three separate layers and describe their function. 3. Define the cerebrospinal fluid, and list the functions of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). 4. Describe the routes of infection for the central nervous system. 5. Explain the host defense mechanisms that protect the central nervous system from infection. 6. Define meningitis, and describe the two major types of meningitis including the etiologic agents. 7. When discussing the etiology of acute meningitis, explain the host predisposing factors for the neonate and identify the most commonly associated bacterial pathogens. 8. Discuss how the advent of the Hib vaccine in the United States has helped to prevent pediatric cases of meningitis. 9. Compare acute and chronic meningitis; outline the distinguishing symptoms and CSF findings for each, including cell counts and chemistry laboratory results. 10. Explain the disease processes for encephalitis and meningoencephalitis. 11. Discuss two ways that meningoencephalitis infections, brain abscesses, or other CNS infections are caused by parasites; identify the associated infecting organisms and the population of patients at increased risk for developing these conditions. 12. Explain the collection, transport, and specimen storage requirements for CSF; include specimen processing and the appropriate distribution of specimen throughout the laboratory. 13. List the culture media used to identify the causative agent of meningitis in bacterial, mycobacterial, and fungal infections; what incubation conditions are required for each type of organism? Between and around the meninges are spaces that include the epidural, subdural, and subarachnoid spaces. The relative location of the meninges and spaces to one another in the brain are depicted in Figure 71-1. The location and nature of the meninges and spaces are summarized in Table 71-1. TABLE 71-1 Inner Coverings (Meninges) of the Brain, Spinal Cord, and Surrounding Spaces CSF is found in the subarachnoid space (see Table 71-1) and within cavities and canals of the brain and spinal cord. There are four large, fluid-filled spaces within the brain referred to as ventricles. Specialized secretory cells, called the choroid plexus, produce CSF. The choroid plexus is located centrally within the brain in the third and fourth ventricles. Approximately 23 mL of CSF are contained within these ventricles in an adult. The fluid travels around the outside areas of the brain within the subarachnoid space, driven primarily by the pressure produced initially at the choroid plexus (Figure 71-2). By virtue of its circulation, chemical and cellular changes in the CSF may provide valuable information about infections within the subarachnoid space. Organisms may gain access to the CNS through several primary routes: • Hematogenous spread: followed by entry into the subarachnoid space through the choroid plexus or through other blood vessels of the brain. This is the most common route of infection for the CNS. • Direct spread from an infected site: the extension of an infection close to or contiguous with the CNS can occasionally occur; examples of such infections include otitis media (infection of middle ear), sinusitis, and mastoiditis. • Anatomic defects in CNS structures: anatomic defects as a result of surgery, trauma, or congenital abnormalities can allow microorganisms easy and ready access to the CNS. • Travel along nerves leading to the brain (direct intraneural): the least common route of CNS infection caused by organisms such as rabies virus, which travels along peripheral sensory nerves, and herpes simplex virus. Chronic meningitis can often occur in patients who are immunocompromised, although this is not always the case. Patients experience an insidious onset of disease, with some or all of the following symptoms: fever, headache, stiff neck, nausea and vomiting, lethargy, confusion, and mental deterioration. Symptoms may persist for a month or longer before treatment is sought. The CSF usually manifests an abnormal number of white blood cells (usually lymphocytic), elevated protein, and decrease in glucose content (Table 71-2). The pathogenesis of chronic meningitis is similar to that of acute disease. TABLE 71-2 *Must consider CSF glucose level in relation to blood glucose level. Normally, the CSF glucose serum ratio is 0.6, or 50% to 70% of the blood glucose normal value. †About 20% to 75% of cases may have PMN leukocytosis early in the course of infection. Important causes of meningitis in the adult, in addition to the meningococcus in young adults, include pneumococci, Listeria monocytogenes, and, less commonly, Staphylococcus aureus and various gram-negative bacilli. Meningitis caused by the latter organisms results from hematogenous seeding from various sources, including urinary tract infections. The percentage of adults with nosocomial bacterial meningitis at large urban hospitals has been increasing. The various etiologic agents of chronic meningitis are listed in Box 71-1. Viral encephalitis, which cannot always be distinguished clinically from meningitis, is common in the warmer months. The primary agents are enteroviruses (coxsackie viruses A and B, echoviruses), mumps virus, herpes simplex virus, and arboviruses (West Nile virus, togavirus, bunyavirus, equine encephalitis, St. Louis encephalitis, and other encephalitis viruses). Other viruses—such as measles, cytomegalovirus, lymphocytic choriomeningitis, Epstein-Barr virus, hepatitis, varicella-zoster virus, rabies virus, myxoviruses, and paramyxoviruses—are less commonly encountered. Any preceding viral illness and exposure history are important considerations in establishing a cause by clinical means. Since 1999, with the first debut of West Nile in the United States, the West Nile virus has been an important consideration in the diagnosis of viral encephalitis. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports that the incidence of West Nile infection peaked in 2003 with 9862 cases of West Nile infection; 2860 were reported cases of meningitis and encephalitis, resulting in 264 deaths. Since then the rates of infection have dropped: human cases reported to the CDC in 2010 were significantly lower with 1021 total reported cases of West Nile; 629 were neuroinvasive cases resulting in 57 deaths; a state-by-state breakdown of the disease incidence is outlined in Table 71-3. In 2012, a deadly resurgence of West Nile virus occurred, including neuroinvasive and non-neuroinvasive, for a total of 4531 cases through mid-October, according to the CDC. TABLE 71-3 Final 2010 West Nile Virus Human Infections in the United States*

Meningitis, Encephalitis, and Other Infections of the Central Nervous System

General Considerations

Anatomy

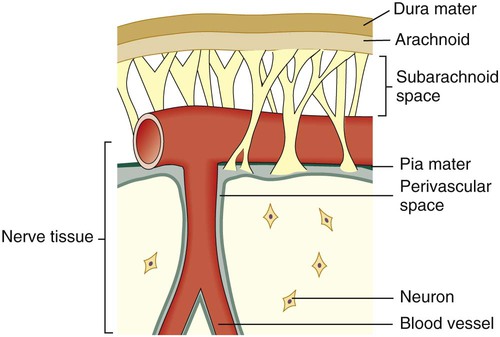

Coverings and Spaces of the CNS

Anatomic Structure

Relative Location

Key Features

Epidural space

Outside the dura mater yet inside the skull

Cushion of fat and connective tissues

Dura mater

Outermost membrane

Membrane that adheres to the skull; white fibrous tissue

Subdural space

Between the dura mater and the arachnoid membrane

Cushion of lubricating serous fluid

Arachnoid membrane

Between the dura mater and pia mater

Delicate, cobweb-like membrane covering the brain and spinal cord

Subarachnoid space

Beneath the arachnoid membrane

Contains a significant amount of CSF in an adult (~125-150 mL)

Pia mater

Beneath the subarachnoid space

Adheres to the outer surface of the brain and spinal cord; contains blood vessels

Cerebrospinal Fluid

Routes of Infection

Diseases of the Central Nervous System

Meningitis

Purulent Meningitis.

Acute.

Clinical Setting

Leukocytes/mm3

Predominant Cell Type

Protein

Glucose*

Normal

0-5

None

15-50 mg/dL

45-100 mg/dL

Viral infection

2-2000 (mean of 80)

Mononuclear†

Slightly elevated (50-100 mg/dL) or normal

Normal

Purulent infection

5-20,000 (mean of 800)

PMN

Elevated (>100 mg/dL)

Low (<45 mg/dL), but may be normal early in the course of disease

Tuberculosis and fungi

5-2000 (mean of 100)

Mononuclear

Elevated (>50 mg/dL)

Normal or often low (>45 mg/dL)

Epidemiology/Etiologic Agents-Acute Meningitis.

Encephalitis/Meningoencephalitis

Viral.

State

Neuroinvasive Disease Cases

Non-neuroinvasive Disease Cases

Total Cases

Deaths

Presumptive Viremic Donors*

Alabama

1

2

3

0

0

Arizona

107

60

167

15

31

Arkansas

6

1

7

1

0

California

72

39

111

6

24

Colorado

26

55

81

4

1

Connecticut

7

4

11

0

5

District of Columbia

3

3

6

0

0

Florida

9

3

12

2

1

Georgia

4

9

13

0

1

Idaho

0

1

1

0

0

Illinois

45

16

61

4

5

Indiana

6

7

13

1

0

Iowa

5

4

9

2

1

Kansas

4

15

19

0

1

Kentucky

2

1

3

1

7

Louisiana

20

7

27

0

7

Maryland

17

6

23

2

0

Massachusetts

6

1

7

0

1

Michigan

25

4

29

3

2

Minnesota

4

4

8

0

1

Mississippi

3

5

8

0

2

Missouri

3

0

3

0

0

Nebraska

10

29

39

2

10

Nevada

0

2

2

0

0

New Hampshire

1

0

1

0

0

New Jersey

15

15

30

2

0

New Mexico

21

4

25

1

6

New York

89

39

128

4

16

North Dakota

2

7

9

0

0

Ohio

4

1

5

0

0

Oklahoma

1

0

1

0

1

Pennsylvania

19

9

28

0

0

South Carolina

1

0

1

0

0

South Dakota

4

16

20

0

0

Tennessee

2

2

4

0

1

Texas

77

12

89

6

14

Utah

1

1

2

0

3

Virginia

4

1

5

1

2

Washington

1

1

2

0

0

Wisconsin

0

2

2

0

1

Wyoming

2

4

6

0

0

Totals

629

392

1021

57

144 ![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree