Chapter 25 Melanocytic nevi

Ephelide

Clinical features

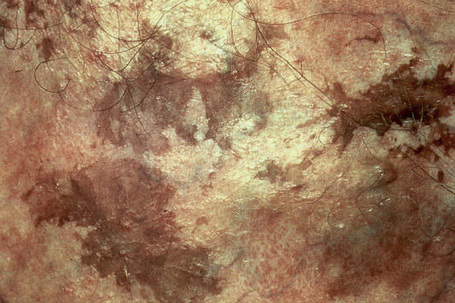

Ephelides (freckles) are extremely common lesions that present as clusters of small (approximately 2.0 mm diameter), uniformly pigmented macules (Fig. 25.1).1–5 They are directly related to exposure to sunlight and are much more conspicuous in summer than in winter. Sites of predilection therefore include the nose, cheeks, shoulders, and dorsal aspects of the hands and arms.2 Although virtually everyone shows some degree of freckling, ephelides are particularly common and numerous in individuals with red hair and blue eyes, where there is probably an autosomal mode of inheritance.5 Ephelides present in childhood, increasing in frequency in adults and typically regressing in the elderly.2,5 There is a predilection for females. High levels of freckling may indicate a raised susceptibility to the later development of melanoma.6 Similarly, increasing numbers of freckles correlate with a higher frequency of acquired melanocytic nevi.7 Otherwise, although a cosmetic nuisance, they are of no clinical importance.

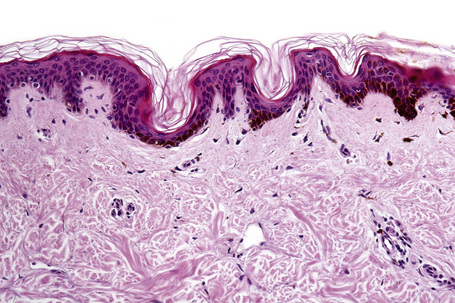

Histological features

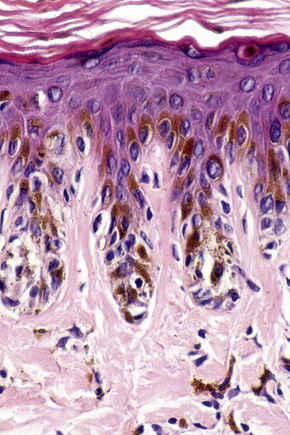

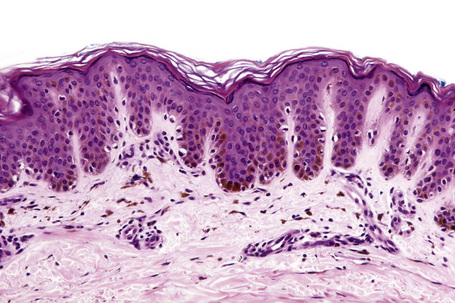

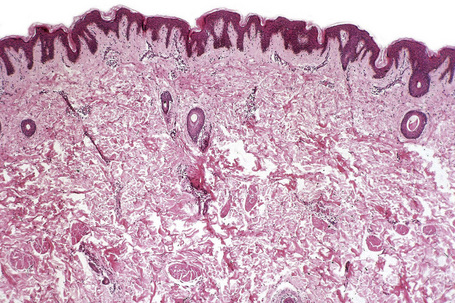

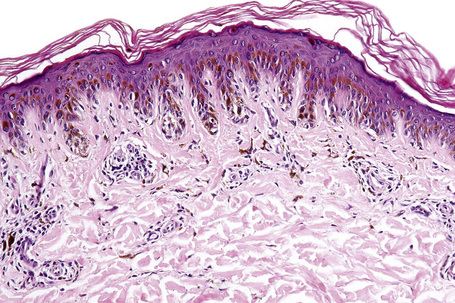

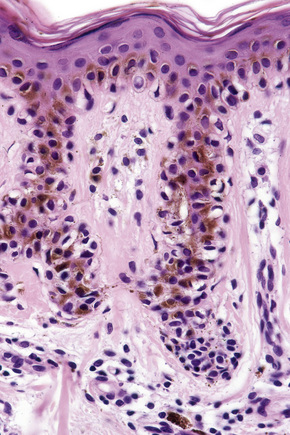

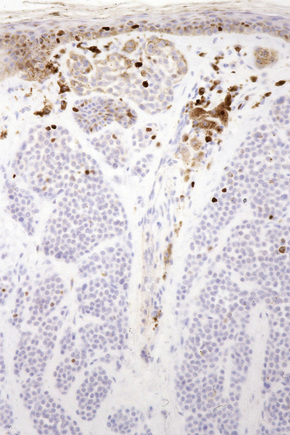

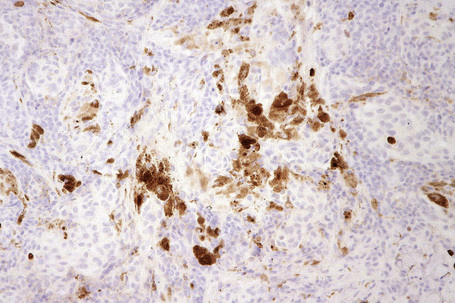

Ephelides are characterized by excessive keratinocyte pigmentation associated with normal or even diminished numbers of melanocytes (Fig. 25.2).8,9 The epidermal architecture is normal. Solar elastosis is not a feature of ephelides.

Ultrastructurally, the melanocytes contain enlarged spherical granular melanosomes in contrast to the striated ellipsoid forms seen in normal white skin.10

Lentigo simplex

Clinical features

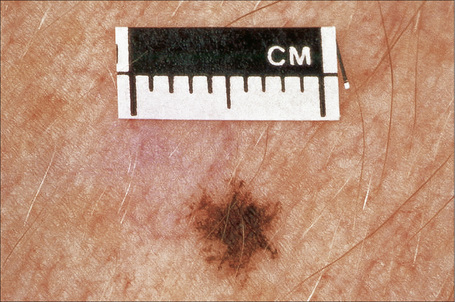

Lentigo simplex is a very common melanocytic lesion. Lesions – which are small (1–5 mm), uniformly pigmented, brown to black, sharply circumscribed macules – may be found anywhere on the integument, the conjunctivae, and mucocutaneous orifices (Fig. 25.3).1,2 They often develop in childhood (juvenile lentigo) and become more conspicuous during pregnancy. Rarely, numerous lentigines may develop following an infection or an exanthem and exceptionally they are generalized (generalized lentigines, lentigines profusa).1,3 Segmental lentigines have also been documented.4 Development of simple lentigines limited to areas treated with tacrolimus has recently been reported in children with atopic dermatitis.5 Simple lentigines have also been described in association with type I hereditary punctate palmoplantar keratoderma.6 Hyperpigmentation and increased numbers of lentigines are features of Addison’s disease. Simple lentigines have no malignant potential and, in contrast to ephelides, have no connection with sunlight.

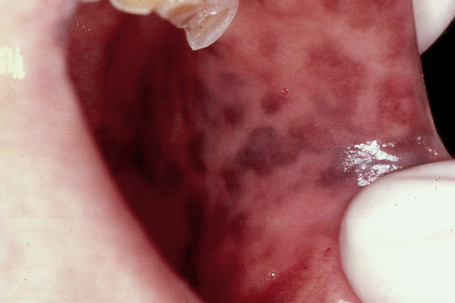

Lentigines assume a particular importance when their presence is associated with a variety of inherited systemic conditions, including Peutz–Jeghers, LEOPARD (multiple lentigines) and Carney’s syndromes, centrofacial lentiginosis, and Laugier–Hunziker syndrome (idiopathic lenticular mucocutaneous pigmentation). The last is characterized by oral melanotic macules and longitudinal pigmentation of the nails (Figs 25.4, 25.5).

Fig. 25.4 Laugier-Hunziker syndrome: oral melanotic macules.

By courtesy of S.-B. Woo, MD, Harvard Medical School, Boston, USA.

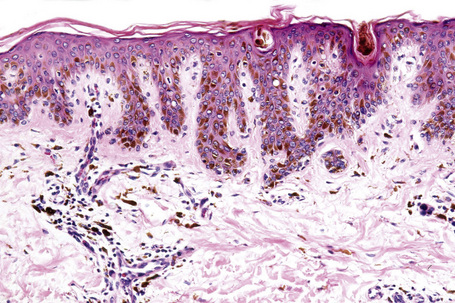

Histological features

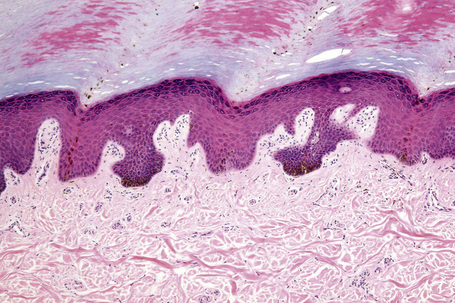

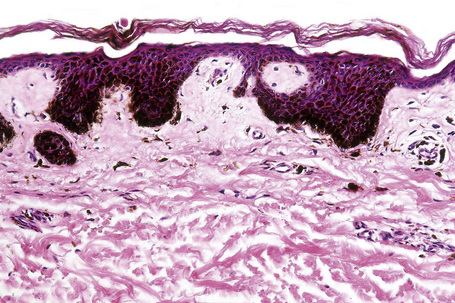

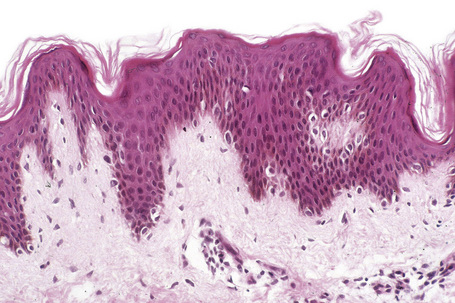

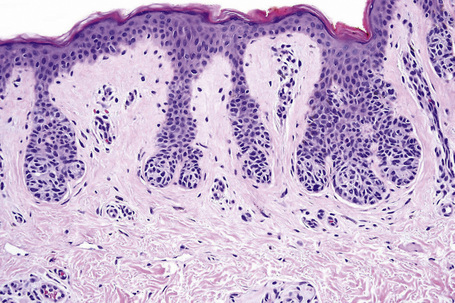

The histological features are those of slight to moderate elongation of the epidermal ridges associated with an increased number of basally located melanocytes (Figs 25.6, 25.7).1,2 Generally, no atypia of melanocytes is seen. There is no junctional activity and pigmentation is increased, both within the epidermis and within melanophages in the papillary dermis. Rarely, giant melanosomes (macromelanosomes) may be identified (Fig. 25.8). A superficial dermal lymphohistiocytic infiltrate is often present. Not uncommonly, lentigo and junctional nevus may coexist – lentiginous junctional nevus (Fig. 25.9).

Interestingly, a recent study failed to demonstrate the presence of BRAF V600E mutations in simple lentigo.7 However, BRAF V600E mutations have been demonstrated in 17% of lentiginous/junctional nevi, in 55% of compound nevi, and in 78% of intradermal nevi.7

Oral melanoacanthoma

This disorder, also known as melanoacanthosis, is discussed under pathology of the oral cavity.

Acral lentigo

Clinical features

Acral lentigines are small, 1–5 mm diameter, circumscribed pigmented macules that present on the palms and soles.1,2 They are seen more often in blacks than in whites. Eruptive acral lentigines have been reported in patients with AIDS, and also in patients with diffuse large cell lymphoma, breast cancer, gastric adenocarcinoma, and advanced stage melanoma.3–5 Acral lentigines are devoid of sinister potential.

Carney’s complex

Lentigines are a feature of Carney’s complex (Fig. 25.11). This topic is discussed under disorders of pigmentation, epithelioid blue nevus, and superficial angiomyxoma.

Centrofacial lentiginosis

Clinical features

Centrofacial lentiginosis is a rare autosomal dominant condition in which patients develop a characteristic zone of pigmented macules, particularly about the central region of the face (Fig. 25.12).1–3 They may also have a variety of skeletal abnormalities including high arched palate, dental malpositions, cervical or cervicothoracic kyphosis, funnel chest, winged scapulae, spina bifida, hammer toes, bilateral pes cavus, and sacral dehiscence.3 They can also suffer from neuropsychiatric disturbances including mental retardation, behavioral disturbances, and epilepsy.3 Endocrine dysfunction, including goiter, hypothyroidism, and calcium metabolism abnormalities, has occasionally been documented.3 An association of centrofacial lentiginosis and giant nevus spilus developing on the left side of the upper back in a dermatomal distribution has been reported in a child.4

Actinic lentigo

Clinical features

Actinic lentigines (also known as lentigo senilis, solar lentigo, senile freckle, senile lentigo, liver spot) are benign, irregular, macular lesions that commonly develop on sun-damaged skin of the middle aged and elderly, and are therefore most numerous on the face and dorsal aspects of the hands and forearms (Figs 25.13, 25.14).1–3 Both acute and chronic sun exposure have been implicated in their pathogenesis.4 It has been proposed that actinic lentigines, especially those that are large, irregularly sized, and located on the upper back and shoulders, serve as a clinical marker of past severe sunburn.5,6

Actinic lentigines measure 0.1–1.0 cm or more in diameter, have a tendency to coalesce, and vary from light to dark brown in color. Caucasians are particularly affected.7 The lesions may be clinically mistaken for lentigo maligna.8

Histological features

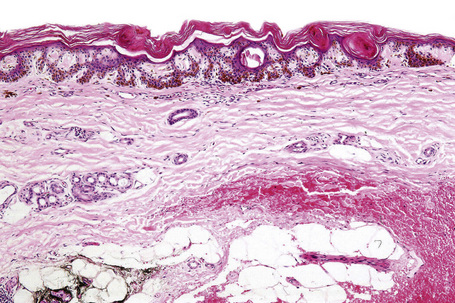

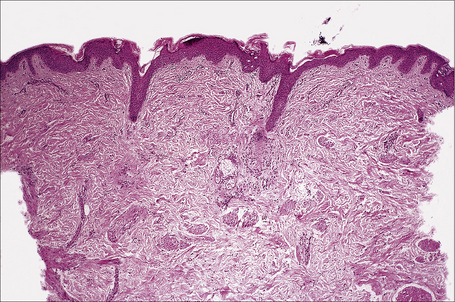

Actinic lentigo usually develops against a background of solar elastosis. There may be slight hyperkeratosis. The epidermis shows extension of the rete ridges to form budlike processes expanding into the papillary dermis (Fig. 25.15). The inter-ridge epithelium is often atrophic. The melanocytes may be normal or slightly increased in number, but appear to be functionally hyperactive because there is a marked increase in the amount of melanin production (Fig. 25.16). A pivotal role for fibroblast-derived growth factors in regulating hyperpigmentation has recently been suggested.9 Mild nuclear hyperchromatism and nuclear irregularity is sometimes seen as a reflection of the chronic actinic exposure. Similar changes may be evident in apparently normal skin from sun-exposed sites.

In some examples, epidermal proliferation may lead to a reticular pattern due to the formation of anastomoses between adjacent attenuated ridges.10 Occasionally, formation of small horn cysts can result in histological overlap with adenoid seborrheic keratosis. Interestingly, similar genetic alterations, namely mutations of the FGFR3/PI3K pathway, have been demonstrated in both actinic lentigo and adenoid seborrheic keratosis, suggesting a possible relationship at molecular level.11,12

Actinic lentigo is sometimes associated with a slight increase in collagen within the papillary dermis. Pigmentary incontinence is often evident and a slight chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate is usually seen in the adjacent dermis. Some (but not all) authors believe that actinic lentigo may evolve into large cell acanthoma (see tumors of the surface epithelium).13,14

Ultrastructurally, the melanocytes contain increased numbers of morphologically normal melanosomes.2

PUVA and sunbed lentigines

Clinical features

Long-term psoralen photochemotherapy (PUVA) may be complicated by a variety of cutaneous pigmentary changes including variable hyper- and hypopigmentation, vitiligo-like features, and multiple lentigines.1–5 PUVA lentigines are dose-dependent, irregular, small, brown–black macules that are particularly seen on the shoulders, upper back, and limbs (Fig. 25.17).3,4 They are commonly numerous. Males are more often affected than females and skin types I and II are particularly at risk. Similar lesions have occasionally been described in patients, including one with systemic lupus erythematosus, following the use of sunbeds for artificial tanning.6–8 Lesions tend to regress after therapy is discontinued.4 Development of PUVA lentigines has been reported at the sites of mycosis fungoides lesions, as well as in normal and vitiliginous skin.9,10

Pathogenesis and histological features

A recent study has demonstrated the presence of T1799 BRAF mutations in 33% of PUVA lentigines.11

Histologically, PUVA lentigines show a variety of features.1–5,12,13 In some, there is increase in basal cell pigmentation with no increase in melanocyte numbers, reminiscent of an ephelide, whereas others resemble lentigines with pronounced rete ridge elongation and increased numbers of melanocytes (Fig. 25.18). Melanocytic nuclear atypia including enlargement, pleomorphism, and hyperchromasia, multinucleation, and giant melanosomes has been described.12,13 There does not appear to be any link between PUVA lentigines and development of melanoma.5

Epidermal abnormalities, including dyskeratosis and actinic keratosis-like features, may also sometimes be observed.14

Ink spot lentigo

Clinical features

Ink spot lentigo (reticulated black solar lentigo, reticular lentigo, acquired reticulated lentigo, reticulated melanotic macule) is a recently documented rare variant of lentigo; it is particularly important because clinically it may be confused with melanoma. It affects fair-skinned individuals with red to blond hair and blue eyes (skin types I and II) and presents on a background of solar-damaged skin as a usually solitary, irregular, reticulated black macule with a wiry or beaded appearance (reminiscent of an ink spot) (Fig. 25.19).1–3 Although the features may be clinically worrying, the lesion is completely benign. Ink spot lentigo can exceptionally develop in the background of a nevus spilus.4

Histological features

Ink spot lentigo shows lentiginous hyperplasia with very marked basal cell hyperpigmentation, rete-tip accentuation and characteristic achromic skip areas (Fig. 25.20).1–3 Melanocytes may be normal or slightly increased in number, but there is no cytological atypia or junctional activity. Pigmentary incontinence is usually evident and a perivascular chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate is commonly present.

Becker’s nevus

Clinical features

Becker’s nevus (pigmented hairy epidermal nevus, Becker’s melanosis, melanosis neviformis Becker) is an androgen-dependent organoid lesion that becomes more prominent after puberty.1 It is uncommon and probably shows an equal sex distribution, although lesions in females are said to be more difficult to appreciate than in males.1 While all races may be affected, there appears to be a predilection for non-whites.2 It usually presents in the second decade, initially as a light to dark-brown enlarging macular lesion, which subsequently shows hypertrichosis (Fig. 25.21).1,3–6 Although most frequently the chest, shoulder or upper arm are involved, examples have occurred everywhere on the skin surface. Lesions on the scalp or face can be associated with asymmetrical growth of scalp hair or beard.7,8 Sometimes they are multiple, and familial examples have been recorded.9 Rarely, Becker’s nevus may be congenital.10 Linear distribution of congenital Becker’s nevus following Blaschko’s lines, giant bilateral Becker’s nevus over the back, chest and upper arms, as well as symmetrical bilateral Becker’s nevus on the anterior chest have also been reported.11–13 Of particular importance is the occasional association of Becker’s nevus with developmental anomalies – the so-called pigmented hairy epidermal nevus syndrome (e.g. breast and limb hypoplasia, pectus excavatum, spina bifida, scoliosis, and hypoplasia of subcutaneous fatty tissue).1,3,6,14 A case in which a scalp lesion occurred with underlying loss of cranium has been documented.15

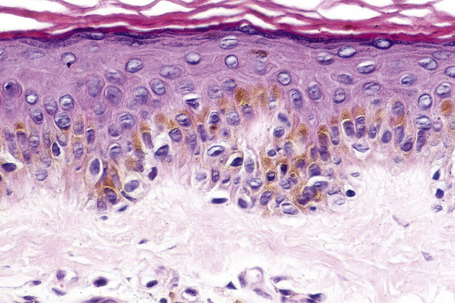

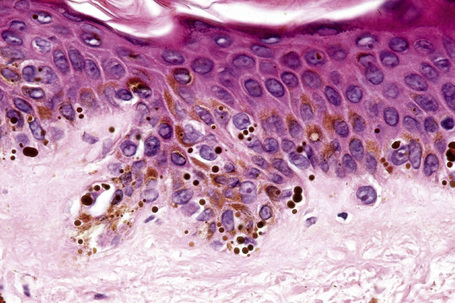

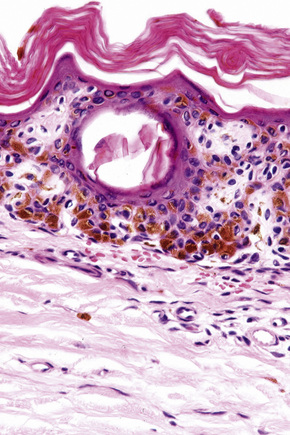

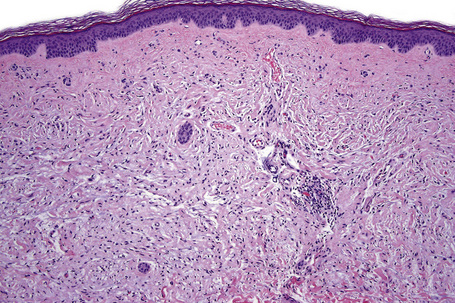

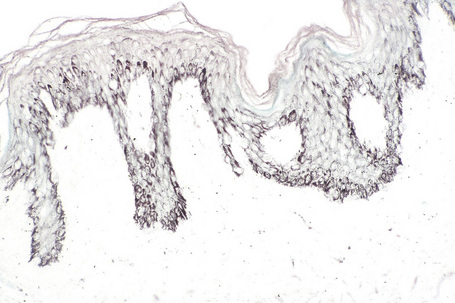

Histological features

The features are subtle, comprising slight hyperkeratosis, variable acanthosis and elongation of the epidermal ridges, accompanied by increased pigmentation in the basal region (Figs 25.22–25.24). Additional changes can include flattening of the epidermis, keratotic plugging, and fusion of two or three neighboring elongated rete ridges.16 In contrast to uninvolved epidermis, epidermis of Becker’s nevus shows increased expression of androgen receptors.16 Melanocytes often appear increased in number, but there is no evidence of proliferative activity.17 The superficial dermis may contain melanophages and a mild perivascular chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate is sometimes present.

Fig. 25.24 Becker’s nevus: the increased pigmentation may be accentuated by the Masson-Fontana reaction.

In occasional lesions the reticular dermis contains large numbers of hamartomatous, irregular, enlarged smooth muscle fibers (Fig. 25.25).18–21 Associated dermal fibrosis, sebaceous hyperplasia, localized acneiform lesions, solitary plexiform neurofibroma, basal cell carcinoma, compound melanocytic nevus, lichen planus, a psoriasiform dermatitis suggestive of an inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus, and hyperkeratosis with focal diminution of granular cell layer (e.g. ichthyotic changes) have also been documented.3,21–24

Ultrastructural studies have revealed an increased number and size of compound melanosomes within basal keratinocytes.3 An increase in the number of melanosomes per complex may also be evident.

Melanocytic nevus

Melanocytic nevus (banal nevus) is a benign tumor that usually presents in childhood and adolescence. The sex distribution is equal. An average white individual can expect to develop 15–40 such lesions during life, reaching the maximum number in the third decade before regression to virtual disappearance by the eighth and ninth decades.1–5

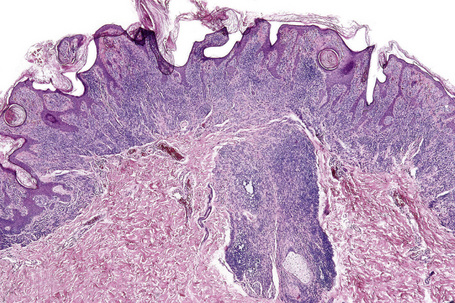

In addition to those derived from hair-bearing skin, melanocytic nevi may develop on glabrous skin, beneath fingernails and toenails, within the conjunctivae and uveal tract, and mucosae (Fig. 25.26). They have an ordered and histologically defined natural history, which may to some extent be predicted from their clinical appearance. Their existence commences as a focus of melanocytic proliferation (junctional activity) within the lower reaches of the epithelium, the so-called junctional nevus. This progresses to the presence of melanocytes within both the epidermis and the dermis, which is the compound nevus. Further development results in a completely intradermal lesion called the dermal nevus.6

Fig. 25.26 Conjunctival junctional melanocytic nevus: there is uniform pigmentation and a regular border.

By courtesy of the late M. Beare, MD, Royal Victoria Hospital, Belfast, N. Ireland.

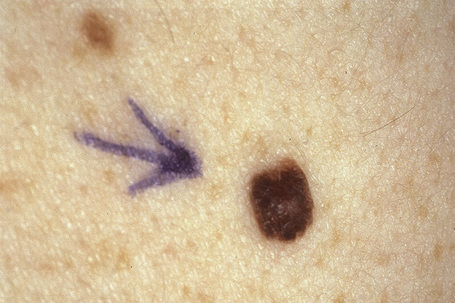

While there is unquestionable malignant transformation on occasions in these lesions, such events are rare; therefore, there is no indication for widespread prophylactic excision of otherwise typical melanocytic nevi (Figs 25.27, 25.28). It has been estimated that the likelihood of any one nevus evolving into melanoma is roughly 1/100 000.7 Subsequent mortality is of the order of 1/500 000 original nevi. However, the prevalence of nevi is of major epidemiological importance, increased numbers correlating with a greater risk of subsequent development of melanoma, of superficial spreading and nodular subtypes.8–10 Lentigo maligna melanoma does not derive from pre-existent nevi and is not related to their prevalence. In young children and adolescents in whom these lesions are at an early stage of development, increased pigmentation is to be anticipated. However, in adults, evidence of junctional activity is to be viewed with caution; it is those nevi with increasingly marked pigmentation, or appearing de novo in the older age groups, which are often excised for histological evaluation.

Clinical features

Melanocytic nevi first appear in early childhood and increase in number during the second and third decades.5,6,11–13 In males, the head, neck, and trunk are particularly affected whereas in females the upper and lower limbs are more often involved.5,12,14,15 Distribution of acquired melanocytic nevi in an agminate (grouped) pattern can occasionally be seen.16 Melanocytic nevi involute during middle age and most have completely regressed in the elderly. They are more common in individuals with pale skin and light-colored eyes.10,17 Melanocytic nevi are much less frequently seen in Asians and Afro-Caribbeans.10 In these races, the acral sites are particularly affected.1 Dark-brown or black hair correlates with increasing numbers of nevi whereas red hair appears to protect.8,10 Development of melanocytic nevi is related to the extent of sun exposure during the first two decades of life.17–19 Intermittent intense sunlight is of greater importance than chronic exposure.12 In fact, chronic sun exposure correlates with low levels of nevi (i.e. it appears to be protective).14 Increasing nevus counts are found in individuals who tend to sunburn rather than tan following sun exposure and correlate with the degree of freckling.10,20,21 As these factors are also important in the etiology of melanoma, high levels of freckles and nevi at an early age may be of predictive value.

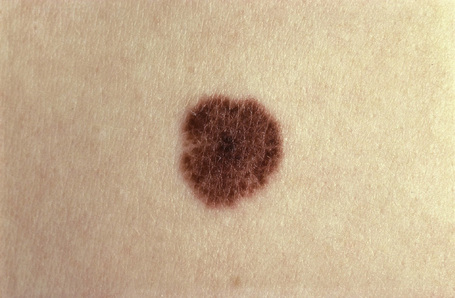

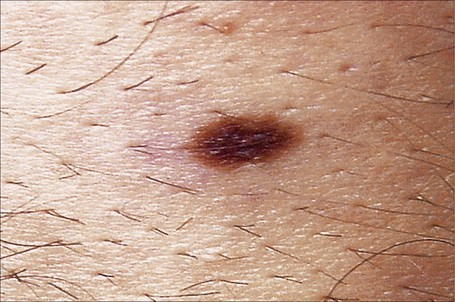

Melanocytic nevi present a variety of features depending upon their stage of evolution. Junctional nevi are usually macular or slightly raised, up to 0.5 cm in diameter and from light to dark brown in color (Figs 25.29–25.31). They are well circumscribed with a regular border and are usually uniformly pigmented, but sometimes the central area is darker. Typically, the skin lines can be clearly discerned on the surface of the lesion.

Fig. 25.29 Junctional melanocytic nevus: the lesion is small. Note the uniform coloration.

By courtesy of M. Liang, MD, The Children’s Hospital, Boston, USA.

Fig. 25.30 Junctional melanocytic nevus: banal nevi are typically sharply circumscribed.

By courtesy of M. Liang, MD, The Children’s Hospital, Boston, USA.

The compound nevus is raised, sometimes dome-shaped or warty, and often still deeply pigmented (Figs 25.32, 25.33). Occasionally, there are coarse hairs projecting from its surface; plucking these hairs may traumatize the dermal component of the hair follicle, resulting in granulomatous inflammation, which may cause concern to both the patient and clinician as to the possibility of malignant transformation. 8,19

The intradermal nevus is often devoid of pigment and may present as a dome-shaped nodule, a papillomatous lesion or a pedunculated skin tag (Figs 25.34, 25.35).

Fig. 25.34 Dermal melanocytic nevus: presentation as a pale, raised, dermal warty, nodule is a common finding.

From the collection of the late N.P. Smith, MD, the Institute of Dermatology, London, UK.

Nevi may become more highly pigmented under the influence of pregnancy or the oral contraceptive pill.22 There is, however, no evidence that pregnancy in any significant way stimulates their development or alters the biological potential of pre-existent nevi.5

Histological features

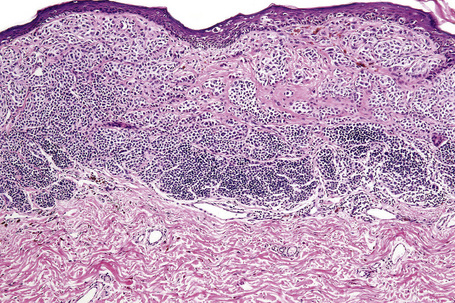

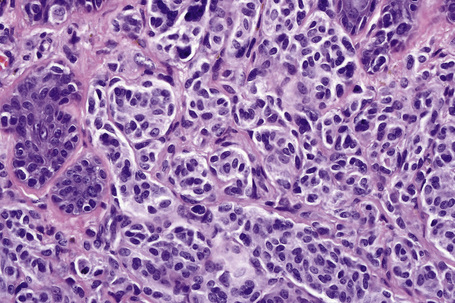

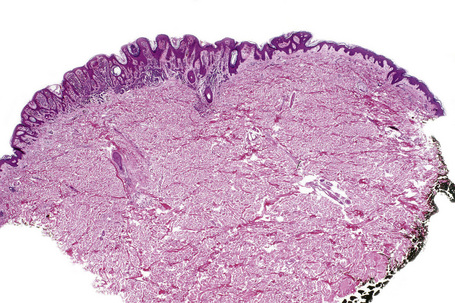

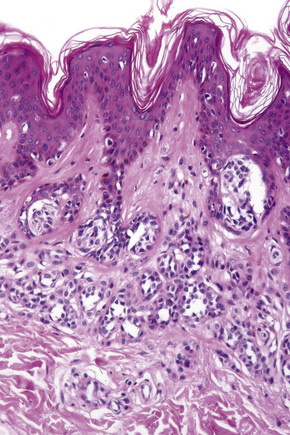

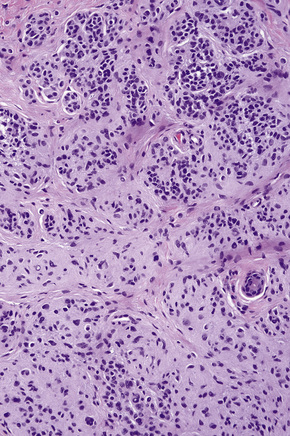

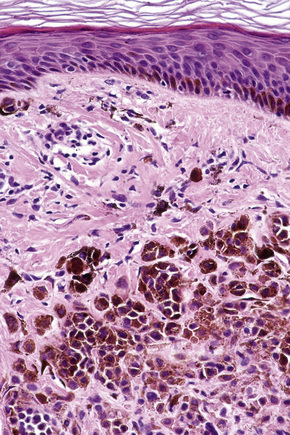

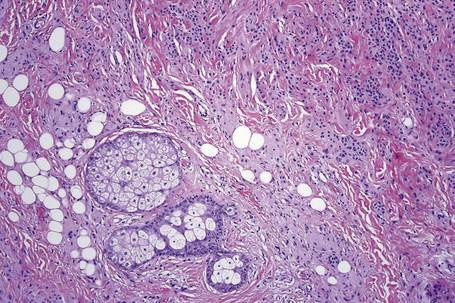

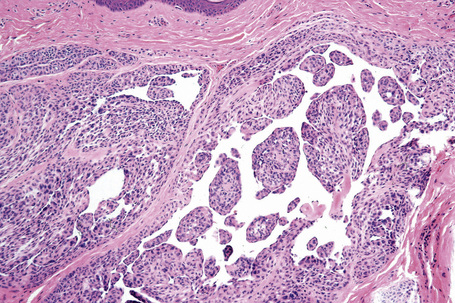

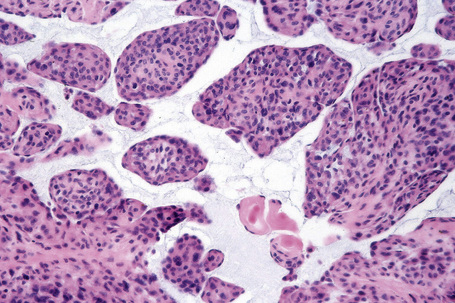

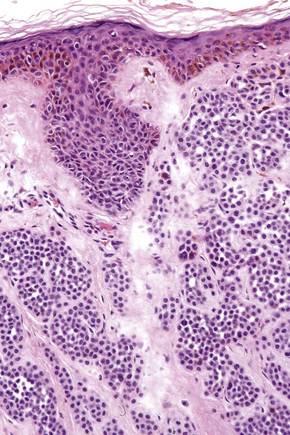

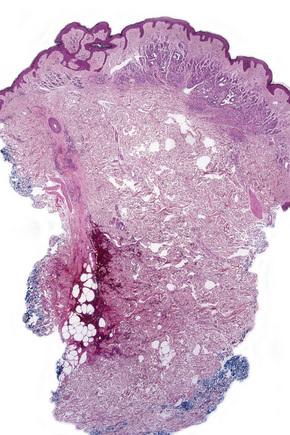

In the earliest stage of development, junctional nests of melanocytes appear in the lower aspect of the epidermis (confined by the basement membrane), usually within the tips or, less often, sides of sometimes broadened and elongated epidermal ridges (lentiginous junctional nevus) (Figs 25.36, 25.37). The melanocytes may be polygonal and epithelioid or more rarely spindled with clear to pale staining or lightly eosinophilic cytoplasm, and contain uniform round to oval small nuclei with prominent nucleoli (type A nevus cells) (Figs 25.38, 25.39). The cytoplasm typically contains sparse, evenly distributed, delicate melanin granules. In benign junctional nevi, growth is towards dermal involvement. Any tendency for melanocytes to spread towards the upper reaches of the epidermis (pagetoid spread) is suggestive of malignant change and should be viewed with caution. Melanocytes between epidermal ridges may sometimes appear increased in number.2 By definition, junctional nevi are solely intraepidermal; however, in heavily pigmented variants, melanin is typically present in macrophages (melanophages) within the papillary dermis (pigmentary incontinence).

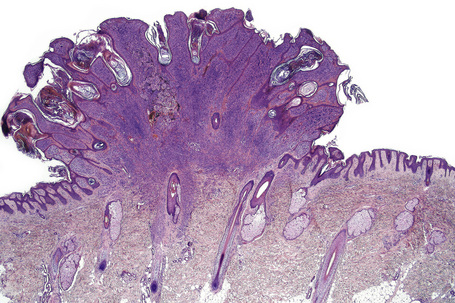

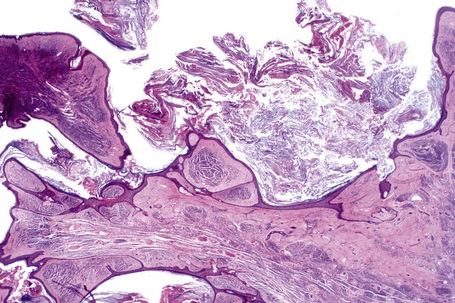

In addition to junctional activity, compound nevi show nests and strands of nevus cells within both the papillary and the superficial reticular dermis (Figs 25.40–25.43). Compound banal nevi are usually fairly well circumscribed and symmetrical. The junctional component does not typically extend beyond the dermal component, i.e. a shoulder is absent in the majority of banal nevi (compare with dysplastic nevus). It should, however, be noted that a shoulder can sometimes be present in a banal compound nevus, i.e. the presence of a shoulder of itself does not make a nevus dysplastic. Compound nevi may sometimes be associated with marked hyperkeratosis, acanthosis with keratinous pseudocyst formation, and papillomatosis (reminiscent of a seborrheic keratosis), accounting for a warty clinical appearance – so-called papillomatous (verrucous) melanocytic nevus or keratotic melanocytic nevus (Fig. 25.44).23–25 These nevi are more often found in females, and the trunk is the commonest site affected. The change may be related to estrogens as the nevus cells express pS2.25

Fig. 25.44 Verrucous compound nevus: this variant shows gross papillomatosis and very marked hyperkeratosis.

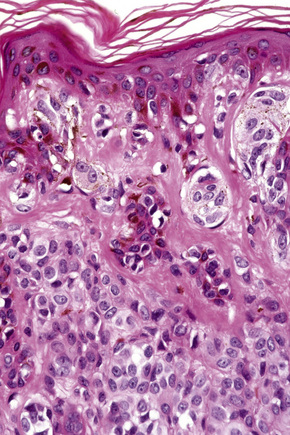

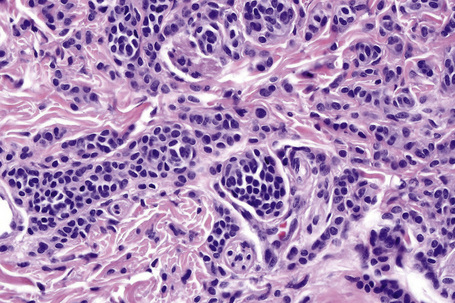

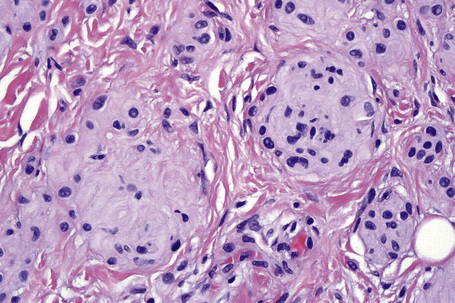

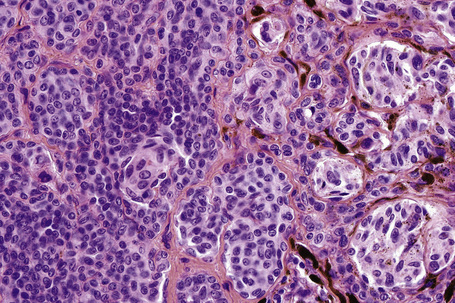

The cells of the more superficial component of the dermal lesion may retain cytological characteristics similar to the junctional nevus. The cells in the deeper aspect are much smaller with less cytoplasm and have dense, more darkly staining nuclei resembling lymphocytes (type B nevus cells) (Figs 25.45–25.47). Mitotic activity can occasionally be seen in the dermal component of an acquired melanocytic nevus (see differential diagnosis). Mitotic activity may also be increased in melanocytic nevi in pregnancy. A recent analysis of dermal mitoses in otherwise banal compound melanocytic nevi has demonstrated the mean number of 0.024 dermal mitoses per square millimeter.26 Mitoses are normal and never atypical, evenly distributed, usually located in the upper half of the dermis, and do not appear in clusters.26 Although isolated regular mitoses can also be seen in the deep dermal melanocytic component, they are about three times less frequent than mitoses in the upper half of the dermis.26 Importantly, banal nevi with dermal mitoses are significantly more common in younger age groups (e.g. between 0 and 20 years of age).26 Therefore, more than an occasional dermal mitosis in older patients should be viewed with caution.

The dermal nevus, the ‘end stage’ of the melanocytic nevus, is typified by progressively less pigmentation with atrophy (so-called nevus maturation) (Fig. 25.48). This is usually accompanied by the accumulation of loose fibrous tissue. Rarely, dense fibrosis may develop, resulting in separation of individual residual melanocytes (desmoplastic nevus) (see below). In some dermal nevi, there may be worrying nuclear pleomorphism and hyperchromatism. The latter, however, appears smudged and the nuclei are devoid of nucleoli and mitotic activity (ancient nevus, nevus with senescent atypia).27

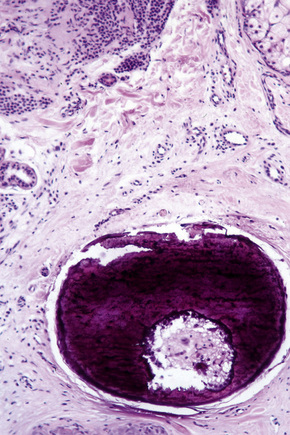

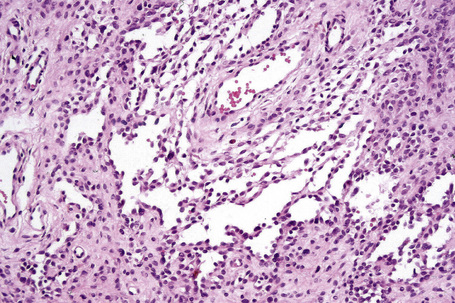

In dermal nevi the melanocytes often develop spindled cell and Schwann cell-like characteristics (neurotization), such as a fibrillar appearance with pale eosinophilic cytoplasm and wavy nuclei (type C nevus cells) (Fig. 25.49). Cholinesterase positivity may be present and often Meissner’s corpuscle-like structures are found (Figs 25.50, 25.51). The cells are nevertheless still truly melanocytic: ultrastructurally, they contain melanosomes. In addition, they are S-100 and dopa positive and do not show Schwann cell morphology, nor do they react with antibodies to myelin basic protein.27 Occasionally, intradermal nevi take on truly neurofibromatous appearances (Fig. 25.52). Other features of ‘maturation’/senescence in dermal nevi include giant cell formation, mucinous degeneration, xanthomatization, and fat accumulation (Figs 25.53–25.55).3 More rarely, changes include calcification and bone formation (usually based on a degenerate hair follicle) (Fig. 25.56). Lesions with bone formation are known as osteonevus of Nanta. A not uncommon observation is the presence of pseudovascular spaces imparting an angiomatous-like appearance (Figs 25.57, 25.58). The cause of this change is unknown although it is probably artifactual and may relate to the effect of a local anesthetic. Immunohistochemical studies using endothelial cell markers are invariably negative.28,29 The cells lining the spaces are of melanocytic derivation and label positively with S-100 protein. Amyloid may rarely be identified within a nevus.30 Exceptionally, a nevus may be accompanied by proliferation of the sweat gland epithelium; coexistence of nevus and desmoplastic trichoepithelioma is occasionally encountered.31–33 Melanocytic nevus has also been reported in association with a trichoadenoma.34

Fig. 25.57 Dermal nevus: the formation of pseudovascular spaces as shown in this example is a common artifact.

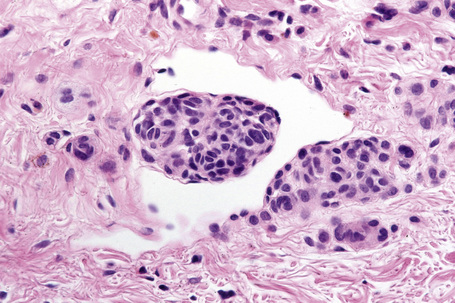

The presence of intravascular melanocytes or evidence of lymphatic involvement is a very disturbing finding and should prompt a thorough search for other features of melanoma. Herniation of a nevus nest into the lumen of a vessel should not be confused with vascular invasion. The distinction can be made by finding a layer of endothelium covering the protruding nevus cells in the benign lesion (Fig. 25.59).

Differential diagnosis

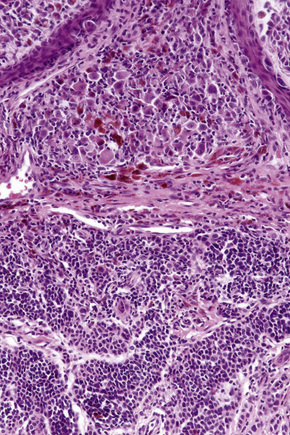

Distinction between a banal nevus and melanoma in the majority of cases is straightforward. Low-power examination of melanoma may reveal obvious intralesional transformation, i.e. the malignant cells stand out as an expansile and often circumscribed nest, nodule or plaque that is cytologically different from the adjacent nevus cells. Additional distinguishing features include the presence of dense pigmentation, lack of maturation, nuclear pleomorphism, mitotic activity, apoptosis, lymphocytic infiltration, and a deep nested growth pattern, which are commonly evident in melanoma but not in intradermal nevi. Upward, intraepidermal or pagetoid spread of melanocytes is an additional feature seen in many melanomas. Caution, however, is advised when viewing sections from neonatal and even childhood nevi when nests and occasionally single cells, sometimes showing mild or even severe cytological atypia, may be identified within the upper reaches of the epidermis (see neonatal nevus).35 Similarly pagetoid spread may be a feature of acral and genital nevi (see below). Reticulin fibers outline nests of melanoma cells whereas they tend to surround individual nevus cells.

Dermal nevus cells may rarely show mitotic activity (Fig. 25.60). Their presence should therefore be viewed with caution and other features suggestive of malignancy sought. Nevoid melanoma may be cytologically similar at a casual glance. Careful inspection, however, reveals asymmetry and lack of circumscription, multiple dermal mitoses, subtle lack of maturation, and nucleolar prominence (see nevoid melanoma).

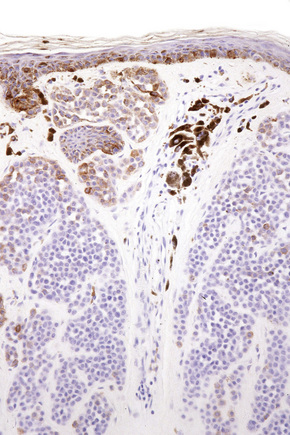

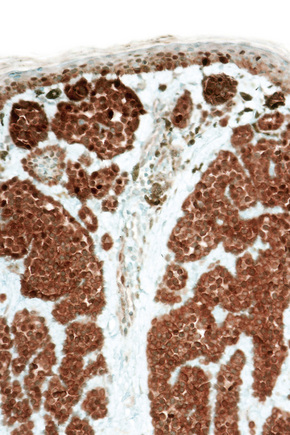

Difficulties are sometimes experienced in differentiating invasive melanoma (particularly the nevoid and small cell variants) from residual benign intradermal nevus cells. The latter is particularly important when assessing tumor thickness or the level of invasion. Immunohistochemistry may be of value in making this distinction. HMB-45 expression is often positive in superficial dermal nevus but is lost with depth (Figs 25.61, 25.62).36 In melanoma, in contrast, the tumor cells are often positive throughout the lesion. p53 protein is not expressed in banal dermal nevi. In contrast, it is frequently present in melanoma.37 In banal nevi, small numbers of Ki-67 and cyclin D1 positive cells may be seen in the more superficial dermal component (Figs 25.63, 25.64). In melanoma, they are usually much more numerous and often they are present throughout the thickness of the lesion.38

Clonal nevus

Clinical features

Many so-called clonal nevi (inverted type A nevi) are clinically unremarkable. Those that are recognized are characterized by a recent change, usually in color, in an otherwise typical banal or (less commonly) congenital nevus.1,2 Alternatively, they may exhibit darker pigmentation in the background of an otherwise uniformly pigmented nevus.3

Histological features

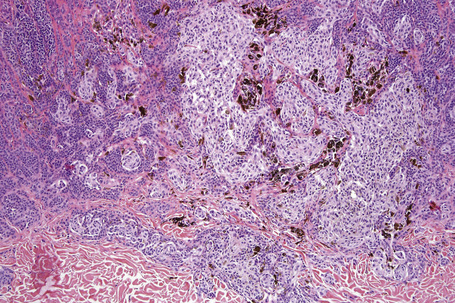

This variant of nevus is characterized by the presence of a usually circumscribed nest or collection of nests in the superficial dermis distinct from the background nevoid population (Figs 25.65–25.68). The melanocytes are typically epithelioid, with often abundant, heavily or finely pigmented cytoplasm and irregular nuclei containing small nucleoli.1,2 Melanophages are usually numerous in the adjacent dermis but a lymphocytic response is absent. Mitoses are absent or extremely rare. The nests stand out against the background population of type B nevus cells; hence the designation inverted type A nevus.

Fig. 25.67 Clonal nevus: high-power view of type A nevus cells with fine pigmentation.

By courtesy of W. Grayson, MD, National Health Laboratory Service, Johannesburg, South Africa.

Differential diagnosis

The vast majority of clonal nevi most likely represent combined or deep penetrating nevi. Melanocytic nevi with a focal atypical epithelioid component (clonal nevus) share similar age, anatomic distribution, and cytological features with the deep penetrating nevus, but lack the deep extension of melanocytes.4

Eccrine centered nevus

Clinical features

Eccrine centered nevus (spotted grouped pigmented nevus) is a rare variant of melanocytic nevus, and has been mainly described in the Japanese.1–3 Lesions, which are typically congenital, consist of a brown plaque covered by numerous dark brown to black 1–3 mm diameter papules or macules. The trunk and thigh are most commonly affected.1,3

Melanocytic nevi at special sites

Nevi on the scalp

Clinical features

Nevi on the scalp occur most frequently on the occipital region, followed by left parietal region, right parietal region, and frontal region (Fig 25.69).1 Their number is related to the number of total body nevi and are most common in the fourth decade of life (mean age 35 years).1 Nevi on the scalp show male predominance.

About 10% of nevi on the scalp show disturbing histological features.2 Such nevi are usually seen in adolescents.2 They have histological features similar to those found on lesions in the mammary line, genital area, and flexural sites.

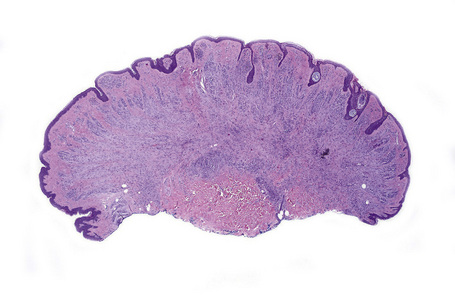

Histological features

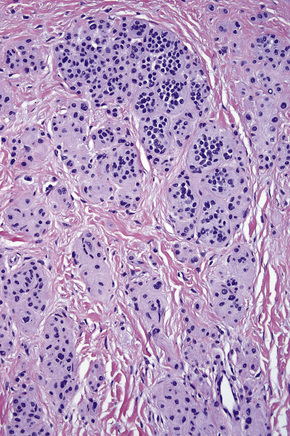

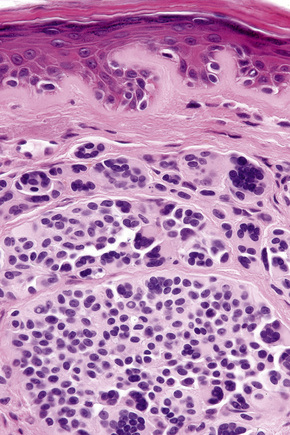

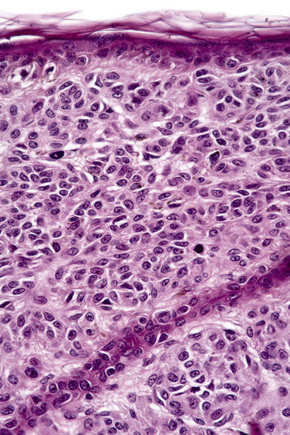

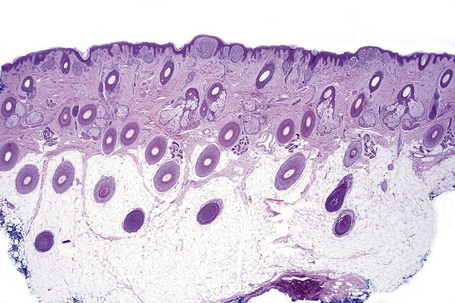

Atypical nevi on the scalp are characterized by asymmetry and poor lateral circumscription (Figs 25.70–25.74).2 The junctional component consists of large nests of melanocytes located at the tips and sides of rete ridges and randomly scattered along the dermoepidermal junction. In addition, melanocytic nests show variation in shape, with frequent bizarre forms and discohesion of tumor cells within them. Involvement of skin adnexa can be seen. Focal lentiginous proliferation along the dermoepidermal junction is frequently present. Melanocytic atypia is usually mild (although occasionally severe cytological atypia is present) and random, and consists of hyperchromatic nuclei and indistinct nucleoli. Upward migration of isolated melanocytes can sometimes be seen in the central part of the lesion. The dermal melanocytic component is unremarkable, although occasionally mitotic activity can be seen.

Fig. 25.70 Scalp nevus: even at low-power magnification, large expansile junctional nests can be appreciated.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree