Chapter Fifteen

Medication Misadventures I: Adverse Drug Reactions

Learning Objectives

After completing this chapter, the reader will be able to

• Define adverse drug reactions (ADRs).

• Discuss the impact of ADRs on health care systems and patients.

• Explain methods for determining causality and probability of an ADR.

• Identify specialty drug information resources that can be used to locate information related to ADRs.

• Classify ADRs based on type and severity.

• Explain when, where, and how to report an ADR to the United States (U.S.) Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

• Explain how to report adverse reactions related to dietary supplements and vaccines.

• Describe the use of technology in ADR monitoring and reporting.

• Use guidelines from national organizations to implement an ADR reporting program.

![]()

Key Concepts

Introduction to Adverse Drug Reactions

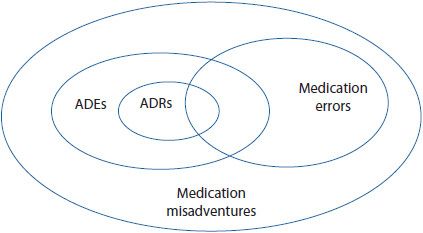

The terminology surrounding adverse drug reactions (ADRs) is often confusing. All adverse drug events (ADEs), ADRs, and medication errors fall under the umbrella of medication misadventures. Medication misadventure is a very broad term, referring to any iatrogenic hazard or incident associated with medications. An ADE is the next broadest term, and refers to any injury caused by a medicine. An ADE encompasses all ADRs, including allergic and idiosyncratic reactions, as well as medication errors that result in harm to a patient.1–5 ADRs and medication errors are the most specific terms. ![]() Adverse drug reaction refers to any unexpected, unintended, undesired, or excessive response to a medicine. A medication error is any preventable event that has the potential to lead to inappropriate medication use or patient harm.1 Figure 15–1 shows one way of graphically classifying these terms. Many of these concepts will be explored in greater depth later in this chapter and in Chapter 16. This chapter focuses on ADRs, highlighting the impact of ADRs, pertinent definitions and classifications, specialty drug information resources, ADR reporting systems, and future approaches to detecting and managing ADRs.

Adverse drug reaction refers to any unexpected, unintended, undesired, or excessive response to a medicine. A medication error is any preventable event that has the potential to lead to inappropriate medication use or patient harm.1 Figure 15–1 shows one way of graphically classifying these terms. Many of these concepts will be explored in greater depth later in this chapter and in Chapter 16. This chapter focuses on ADRs, highlighting the impact of ADRs, pertinent definitions and classifications, specialty drug information resources, ADR reporting systems, and future approaches to detecting and managing ADRs.

Figure 15–1. Relationship among medication misadventures, adverse drug events, medication errors, and adverse drug reactions. (Adapted from Bates DW, et al. Relationship between medication and errors and adverse drug events. J Gen Intern Med. 1995 Apr;10(4):199-205.)

IMPACT OF ADVERSE DRUG REACTIONS IN THE UNITED STATES

All medications, including the inactive ingredients of a product, are capable of producing adverse reactions.6 ADRs account for about 5% to 15% of all hospital admissions, cause patients to lose confidence in their health care providers, and lead to a significant increase in morbidity and mortality.7–13 In 2010, there were over 40,000 deaths due to drug-induced causes, landing ADRs among the 10 leading causes of death in the United States.9

ADRs have economic consequences as well. ADRs result in an annual cost of $5 to $7 billion to the U.S. health care system. Each hospital in the United States spends up to $5.6 million annually as a result of ADEs. After experiencing an ADR, patients spend an average of 8 to 12 days longer in the hospital, increasing the cost of their hospitalization by $16,000 to $24,000.11

The incidence of ADRs for hospitalized patients has been reported to be as high as 28%. Of course, ADRs do not affect hospitalized patients alone. Approximately 20% of the ambulatory population receiving medications suffers from ADRs.10 These outpatient events do not always result in hospitalization, but certainly affect morbidity and patient quality of life. Health care professionals agree that these estimates are somewhat conservative because many ADRs go undetected, unreported, and untreated.10 One review concluded that only 2% to 4% of all ADRs, and fewer than 10% of serious ADRs, are ever reported.11

Although not all adverse reactions can be prevented, a large proportion of them can; the World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that at least 60% of ADRs are preventable. Preventable ADRs may be caused by such factors as the wrong diagnosis of a patient’s condition, incorrect dosing or selection of a prescription medication, interactions with other drugs including dietary supplements, and patients who do not follow the instructions for taking a medication.14 This highlights the need for health care practitioners and health care facilities to engage in the process of systematically preventing and responding to ADRs. WHO terms this pharmacovigilance, or the process of preventing and detecting adverse effects from medications.12

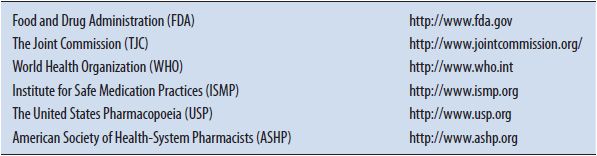

Several agencies and professional organizations across the country have an active role in pharmacovigilance, and contribute efforts to minimize the occurrence and impact of ADRs. In addition to WHO, some of the key organizations include the FDA, The Joint Commission (TJC), and the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP). See Table 15–1. Despite the numerous organizations involved, pharmacovigilance depends heavily on individual health care practitioners, including pharmacists, physicians, and nurses, to take measures to minimize ADRs and report events. Practitioners need to understand the potential for ADRs and be prepared to recognize and prevent such occurrences in order to minimize adverse outcomes.

TABLE 15–1. ORGANIZATIONS INVOLVED IN PREVENTING ADVERSE DRUG EVENTS

Pharmacists play a vital role in the medication use process. Multiple studies have highlighted the tremendous impact individual pharmacists can have on minimizing ADRs.15,16 In one study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, pharmacists began participating in patient rounds in an intensive care unit. By implementing this measure alone, the hospital significantly reduced the incidence of ADRs and saved an estimated $270,000 per year.13

DEFINITIONS

After reading this chapter, the reader should be able to evaluate ADRs and, potentially, develop and implement an ADR surveillance program at their hospital, clinic, or community pharmacy.![]() One of the first steps in establishing an ADR program is to define what each facility or organization categorizes as ADRs. There are many definitions for ADRs that have been described in the literature, including guidance from national and international organizations, as well as individual facilities and practitioners. Several of these definitions are presented below. Rather than getting bogged down in the differences between these many definitions, use this information for guidance when starting to evaluate ADRs and develop an ADR monitoring and reporting system. Remember that institutions, as well as clinicians, use different definitions depending on their practice needs.

One of the first steps in establishing an ADR program is to define what each facility or organization categorizes as ADRs. There are many definitions for ADRs that have been described in the literature, including guidance from national and international organizations, as well as individual facilities and practitioners. Several of these definitions are presented below. Rather than getting bogged down in the differences between these many definitions, use this information for guidance when starting to evaluate ADRs and develop an ADR monitoring and reporting system. Remember that institutions, as well as clinicians, use different definitions depending on their practice needs.

WHO defines an ADR as “a response to a medicine which is noxious and unintended, and which occurs at doses normally used in man.”17 WHO additionally defines the term side effect, which is “any unintended effect of a pharmaceutical product occurring at doses normally used by a patient which is related to the pharmacological properties of the drug.”17 Note that, in clinical practice, side effect is a broad term that may be used synonymously with ADR, or may even refer to an ADE.

Defined by the FDA, an ADR is any “undesirable experience” associated with the use of a drug or medical product in a patient.18 This definition is also fairly broad, and includes adverse events occurring from drug overdose as well as situations involving abuse. The FDA goes on to define an unexpected adverse reaction as one that is not listed in the current labeling for a medication as having been reported or associated with the use of the drug. This distinction is important, because unexpected ADRs are those that the FDA would like health care practitioners to report. (Reporting ADRs to the FDA will be discussed later in this chapter.) This definition focuses on reporting unusual, uncommon, or newly identified ADRs. Although common or expected ADRs are relevant and important, they do not provide the FDA with new or additional safety information. Unexpected drug reactions may be symptomatically or pathophysiologically related to an ADR listed in the current labeling, but may differ from the labeled ADR because of greater severity or specificity. For example, a medication may have abnormal liver function listed in its labeling as an adverse reaction. A health care practitioner should still report a case of hepatic necrosis following administration of the drug, because it represents an unexpected ADR of greater severity.19

Edwards and Aronson propose another definition of an ADR: “An appreciably harmful or unpleasant reaction, resulting from an intervention related to the use of a medicinal product, which predicts hazard from future administration and warrants prevention or specific treatment, or alteration of the dosage regimen, or withdrawal of the product.”20 This is a very practical definition for health care practitioners, because it highlights the need to take action in order to manage the effects of the adverse reaction.

Finally, Karch and Lasagna,21 two prominent researchers in the area of ADRs, define a drug, an ADR, and a patient drug exposure as follows:

Drug: a chemical substance or product available for an intended diagnostic, prophylactic or therapeutic purpose.

Adverse Drug Reaction: any response to a drug which is noxious and unintended and which occurs at doses used in man for prophylaxis, diagnosis or therapy, excluding therapeutic failures. (As stated by the WHO, this definition excludes intentional and accidental poisoning as well as drug abuse situations.)

Patient–Drug Exposure: a single patient receiving at least one dose of a given drug.21

Many institutions use Karch and Lasagna’s definition because it excludes accidental poisonings as well as problems with drugs of abuse.

Remember, these definitions are intended to provide guidance and food for thought; in daily practice, the differences between these descriptions may not be relevant or clinically meaningful. What is important is that individuals find or develop a definition of ADRs that works for the needs of their pharmacy, clinic, or hospital.

Causality and Probability of Adverse Drug Reactions

One of the challenges in defining and managing ADRs is determining causality. How can it be determined whether or not a drug caused a patient’s adverse reaction? Cause and effect is difficult to prove in general, and ADRs are no exception. Many investigators have dealt with this problem by developing and publishing definitions, algorithms, and questionnaires that try to determine the probability of a reaction—that is, the likelihood that an ADR was caused by a particular drug or medication. There are over 30 different published methods for assessing adverse drug reaction causality. They fall into three broad categories22:

1. Expert judgment/Global introspection: This method involves the individual assessment of the event by a health care practitioner, based on his or her clinical knowledge and experience without using any form of standardized tool.

2. Algorithm: This method uses specific questions to assign a weighted score that helps determine the probability of causality in a given reaction.

3. Probabilistic: This method uses Bayesian approaches and epidemiological data to calculate and estimate the probability of causality with advanced statistical methods.

To date, none of these attempts have been able to prove actual causality. These tools, however, are used to determine the probability that a particular drug caused an adverse event and will be described further below.

These algorithms and definitions use several important key concepts.18,23 Dechallenge and rechallenge are often discussed. Dechallenge occurs when the drug is discontinued and the patient is then monitored to determine whether the ADR abates or decreases in intensity. Rechallenge occurs when the drug is discontinued and, after the ADR abates, the same drug is administered in an attempt to elicit the response again. Dechallenge and rechallenge are effective means for establishing a strong case that the drug was responsible for the ADR. Unfortunately, in clinical practice, a rechallenge may not be practical and may actually cause further harm to the patient. Patients who suffer a serious ADR may not be thrilled about experiencing the reaction again in the name of science. Therefore, a rechallenge may not always be practical, but a dechallenge is often essential.

Another important concept to consider is the temporal relationship between the drug and the event. Does the timeframe for development of the ADR make sense? Did the patient’s exposure to the drug precede the suspected ADR? If there are previous reports of the ADR in the literature, do these reports describe a temporal relationship between the drug and the event? Case reports, specialty drug information resources, and package inserts can be helpful in noting if a drug has been known to cause a certain type of reaction in a certain timeframe in the past. Unfortunately, the literature is not likely to be helpful for rare or new ADRs, but this does not discount the fact that a reaction may have occurred.

Naranjo and colleagues23 developed the following definitions to assist in determining the probability of a suspected ADR:

Definite ADR is a reaction that: (1) follows a reasonable temporal sequence from administration of the drug, or in which the drug level has been established in body fluids or tissue; (2) follows a known response pattern to the suspected drug; (3) is confirmed by dechallenge; and (4) could not be reasonably explained by the known characteristics of the patient’s clinical state.

Conditional ADR is a reaction that: (1) follows a reasonable temporal sequence from administration of the drug; (2) does not follow a known response pattern to the suspected drug; and (3) could not be reasonably explained by the known characteristics of the patient’s clinical state.

Doubtful ADR is any reaction that does not meet the criteria above.23

USING ALGORITHMS

![]() Several algorithms have been published that try to incorporate information about an ADR into a more objective form. As described above, these algorithms each use a set of specific questions to determine the likelihood that the drug was responsible for the reaction, and establish a rational and scientific approach to what previously required strictly clinical judgment. Although algorithms are helpful in offering a systematic approach to assessing the probability of ADRs, they can be very time consuming and the results vary significantly according to the interpretation of multiple observers.

Several algorithms have been published that try to incorporate information about an ADR into a more objective form. As described above, these algorithms each use a set of specific questions to determine the likelihood that the drug was responsible for the reaction, and establish a rational and scientific approach to what previously required strictly clinical judgment. Although algorithms are helpful in offering a systematic approach to assessing the probability of ADRs, they can be very time consuming and the results vary significantly according to the interpretation of multiple observers.

In 1979, Kramer and coworkers published a questionnaire composed of 56 yes or no questions (Appendix 15–1).24 This questionnaire includes sections about the patient’s previous experience with the drug or related drugs, alternative etiologies, timing of events, drug concentrations, dechallenge, and rechallenge. Responses to each question are given a weighted value and these values are totaled. The total value then correlates to one of four categories: unlikely, possible, probable, or definite. One of the problems with the Kramer method (as well as other algorithms) is that clinicians can disagree on the weighted values because the user must make subjective judgments for some of the questions. Another problem inherent with this questionnaire is that an unexpected ADR may not score well because of lack of literature or previous experience with the ADR. If the reaction is not universally accepted or in the most recent edition of the Physicians’ Desk Reference, the suspected reaction would score a zero in this section. This makes the method devised by Kramer and associates less useful for new medications and for unexpected or emergent ADRs. Overall, however, the questionnaire provides health care professionals with the opportunity to use a standardized tool. Hutchinson and colleagues evaluated the reproducibility and validity of the Kramer questionnaire and concluded that, although the questionnaire was cumbersome to use, the method was superior to clinical judgment alone.25

Naranjo and colleagues developed an alternative algorithm in 1981 (Appendix 15–2).23 This algorithm asks 10 questions involving the following areas: temporal relationship, pattern of response, dechallenge or administration of an antagonist, rechallenge, alternative causes, placebo response, drug level in the body fluids or tissue, dose-response relationship, previous patient experience with the drug, and confirmation by any other objective evidence. Like the algorithm proposed by Kramer et al, the answer to each question is assigned a score. The score is then totaled and placed into a category from definite to doubtful. In the initial published report of this algorithm, Naranjo and colleagues tested the reproducibility and validity of the algorithm and found that their tool was a valid means of assessing ADRs. Today, the Naranjo algorithm is one of the most commonly used methods to assess adverse drug reaction causality, and has been considered a gold standard of assessing ADR causality. Compared to the method devised by Kramer et al, the Naranjo tool is much quicker to administer. However, it is not without its faults. The tool emphasizes rechallenge and dechallenge, which may pose some problems in evaluating ADRs as described previously. The Naranjo algorithm also asks about a response to placebo, which is rarely (if ever) administered in clinical practice today.

In 1982, Jones and colleagues published an algorithm that allows health care practitioners to answer a series of yes or no questions to determine the probability that an ADR occurred (Appendix 15–3).26 The Jones algorithm asks similar questions as those used in the methods described above, but uses a dichotomous key design. Like the Naranjo algorithm, the tool developed by Jones et al is shorter and quicker to complete than Kramer’s questionnaire. Unlike either Kramer or Naranjo algorithms, the Jones method does not require summation of a score. Of note, the Jones algorithm was originally designed for use in a community health setting, illustrating that the assessment of ADRs is not limited to inpatient or institutional settings only.

All of the algorithms described above possess a certain degree of observer variability. However, each can be used to help determine whether an adverse event was precipitated by a certain drug or drug–drug combination. Michel and Knodel compared the three algorithms by Kramer, Jones, and Naranjo.27 Their study found that the Naranjo algorithm was simpler and less time consuming, and compared favorably to the 56 questions asked by Kramer. Although there was agreement between the Naranjo and Jones algorithms, the study found a higher correlation between the Naranjo algorithm and the Kramer questionnaire. The authors concluded that more data were needed to support the use of the algorithm developed by Jones and colleagues.

A modern approach to assessing the causality of ADRs is being developed by researchers at Butler University College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences.28 Their algorithm, the Butler University Adverse Drug Reaction Causality Assessment Tool (BADCAT), has been proposed as an easy-to-use alternative to traditional methods, and aims to improve the interrater reliability of ADR assessment techniques. BADCAT comprises 11 questions that ask the health care provider to assess the temporal relationship, previous reports of the potential ADR, patient-specific factors such as co-morbidities, dechallenge, rechallenge, and so on. BADCAT is unique in that it also includes an item related to clinical judgment—that is, the clinician’s professional opinion of whether or not the suspected drug caused or contributed to the patient’s adverse reaction. This item is factored into the overall score, which is interpreted as either a highly likely, likely, or probable ADR. BADCAT has not yet been published in its final form, but preliminary results indicate that the tool may demonstrate higher interrater agreement than the Naranjo algorithm.

At this time, no algorithm for assessing the causality or probability of an ADR has been proven superior.29 Therefore, it is reasonable to select a method based on factors such as availability, speed and ease of completing the tool, and clinician preference.

PROBABILISTIC METHODS

A Bayesian approach to assessing adverse reactions has been developed by Lane.30 Using the Bayesian approach, relevant information is collected and a quantitative measure of the odds that a particular drug caused a particular event is calculated. The Bayesian approach has the potential to be an outstanding tool for predicting populations that may be at higher risk for ADRs. However, this method requires complex calculations, significant time investments to develop the model, and the involvement of a statistician.31 Therefore, the Bayesian approach is likely not practical for implementation in individual clinics or hospitals. But WHO is using these methods to analyze data in their international drug monitoring network.20

In addition to the methods for assessing adverse drug reaction causality and probability discussed above, there are also tools for assessing specific types of ADRs. For example, different methods exist for assessing drug-related liver toxicity.32

Case Study 15–1

A patient approaches you at the community pharmacy. She explains that she began taking a dietary supplement called ZygoControl Weight Loss about 6 weeks ago. Every time she takes the product, she feels like her heart is racing, she becomes lightheaded, and her mouth feels dry. These symptoms last about 3 hours and then go away. She asks you if you think ZygoControl Weight Loss is causing these side effects. You research the product and find out that it contains high doses of caffeine and a stimulant called synephrine that is similar to ephedrine.

• In this case, was there a dechallenge? If so, what happened when the suspected product was dechallenged?

• Was there a rechallenge? Is so, what happened?

• Was there a temporal relationship between taking this product and the reaction the patient experienced?

• Based on what you know about this product, is the reaction consistent with its known pharmacology?

• What is the likelihood of this product causing the reaction?

![]()

SPECIALTY RESOURCES FOR ADVERSE DRUG REACTIONS

Methods used to assess the causality of ADRs, including the Kramer and Naranjo algorithms as well as the BADCAT tool, rely in part on previous documentation of the reaction occurring in response to administration of the suspected drug. For common or well-known ADRs, the prescribing information (also called the package insert) and major drug information compendia can be useful. However, for other suspected ADRs, specialty resources may be necessary.

Chapter 3 introduces ADR specialty resources, including gold standards references Meyler’s Side Effects of Drugs and Side Effects of Drugs Annual. This section briefly describes a few additional specialty resources that may be useful.

FDA’s MedWatch program for voluntary reporting of ADRs is discussed later in this chapter and Chapter 16. The results of this program are disseminated through a special section of the FDA Web site dedicated to ADRs and other medication safety topics (http://www.fda.gov/Safety/Medwatch). This online reference contains the FDA’s latest safety alerts and recalls as well as resources for health care professionals. The site also provides monthly summaries of changes to drug labeling that the FDA has made in response to reports from health care providers and others involved in pharmacovigilance.33 Users can sign up to receive safety alerts by e-mail, or follow FDA MedWatch on Twitter using Internet-enabled mobile devices such as smartphones or tablet computers (http://www.twitter.com/FDAMedWatch).

Because the FDA’s Web site can be difficult to navigate, it is perhaps best used for current hot topics or news items related to ADRs. The search function is rudimentary, and searching MedWatch for previous reports of a suspected ADR can be challenging. An alternative solution is DrugCite (http://www.drugcite.com), an independent Web site that uses a series of algorithms to search and report on the FDA’s adverse events database. Although the depth of information provided by DrugCite is minimal, the site can be used to determine whether an adverse reaction has been previously reported to MedWatch in response to a particular drug and, if so, how often.34,35 A mobile DrugCite application is available for Android-based devices.36

Published case reports can also be useful in assessing and evaluating ADRs (see Chapter 5 for more information on evaluating case reports). Reactions Weekly is a weekly publication that indexes and abstracts ADR case reports and ADR-related news from around the world (see also Chapter 3). Because it pulls information from biomedical journals, scientific meetings, and the WHO International Drug Monitoring Programme, Reactions Weekly can be useful for efficiently searching the available information related to a suspected ADR.37 Clin-Alert is a similar publication that summarizes reports of adverse clinical events from more than 100 key research journals, although its focus is primarily on reports of drug–drug interactions (DDIs).38

Classification of Adverse Drug Reactions

Various definitions and terminology have been used to classify ADRs. As discussed above, algorithms such as those developed by Naranjo, Kramer, and Jones have used the definite, probable, possible, and unlikely categories to classify ADRs by their probability. Other classification systems rank ADRs by severity or by their mechanism. When developing an ADR monitoring program, these various systems can be used to determine probability (cause and effect) and severity of ADRs and help describe and quantify data. The data may help identify severity of reactions that are occurring and which medications cause the most severe reactions. Classification systems can also help health care practitioners organize and present data, and facilitate monitoring of ADR trends and potential causative agents. These trends can be used to change prescribing habits or to alert institutions and organizations to potential problems with medications.

CLASSIFYING BY SEVERITY

Karch and Lasagna21 developed a method of classifying ADRs by severity, from minor to severe, as defined below:

• Minor: No antidote, therapy or prolongation of hospitalization is required in response to the ADR.

• Moderate: The management of the ADR requires a change in drug therapy, specific treatment, or an increase in hospitalization by at least 1 day.

• Severe: The ADR is potentially life threatening, causing permanent damage, or requiring intensive medical care.

• Lethal: The ADR directly or indirectly contributes to the death of the patient.

The FDA and WHO also use severity to classify ADRs. According to the these organizations, an ADR is serious when it results in death, is life threatening, causes or prolongs hospitalization, causes a significant persistent disability, results in a congenital anomaly, or requires intervention to prevent permanent damage.14,39

CLASSIFYING BY MECHANISM

Karch and Lasagna also described various mechanisms by which ADRs occur.21 These mechanisms are related to the pharmacologic or pharmacodynamic properties of drugs, and can be used to classify the type of reaction that occurs:

• Idiosyncrasy: an uncharacteristic response of a patient to a drug, usually not occurring on administration.

• Hypersensitivity: a reaction, not explained by the pharmacologic effects of the drug, caused by altered reactivity of the patient and generally considered to be an allergic manifestation.

• Intolerance: a characteristic pharmacologic effect of a drug produced by an unusually small dose, so that the usual dose tends to induce a massive overaction.

• Drug interaction: an unusual pharmacologic response that could not be explained by the action of a single drug, but was caused by two or more drugs.

• Pharmacologic: a known, inherent pharmacologic effect of a drug, directly related to dose.

Classifying the ADR by its mechanism may aid in identifying similar drugs that can be expected to cause a reaction, or may help explain patient-specific reactions to medications.

Implementing a Program

Well-designed programs that monitor and identify ADRs, as well as broadcast information to the medical community, are essential. A later section of this chapter will discuss the importance of reporting suspected ADRs to the FDA and other stakeholders. But before ADRs can be reported, a program for detecting and capturing these reactions must be implemented at a facility or institution.

Prior to implementing an ADR program, the health care facility must educate its staff on the importance and significance of the program. The pharmacy department is in an excellent position to provide this education because of its involvement in the pharmacy and therapeutics (P&T) committee, pharmacokinetic dosing, drug utilization evaluation (DUE), and drug distribution. The pharmacy department can be an excellent resource for developing an ADR program, as well as providing data about ADRs to the P&T committee.

STEPS FOR IMPLEMENTING A PROGRAM

Accrediting bodies like TJC40 require that hospitals and health care organizations have an ADR reporting program. These programs are generally a function of the P&T committee (or other medical staff committee) and the department of pharmacy. ASHP also encourages pharmacists and health care practitioners to take an active role in monitoring adverse events. ASHP has published very specific guidelines on ADR monitoring and reporting as part of its practice standards.41 TJC and ASHP standards can be used as a basis for starting an ADR monitoring program. In addition to the standards, the pharmacy and medical literature are rich with examples of successful programs, some of which will be reviewed in this chapter.

Steps for implementing an ADR monitoring program include the following:

1. Develop definitions and classifications of ADRs that work for the institution. The definitions and classifications in this chapter provide a good starting point for discussion.

2. Assign responsibility for the ADR program within the pharmacy and throughout other key departments. A multidisciplinary approach is an essential factor. This will improve awareness of the monitoring program and increase ADR reporting at all levels of patient care.

3. Develop a program with approval from the pharmacy department, medical staff and nursing department, as well as other appropriate areas within the facility. Cooperation is essential in initiation of a successful program.

4. Promote awareness of the program. Newsletters, e-mails, in-services, grand rounds presentations, and other educational programs are opportunities to increase awareness and garner support for the program.

5. Promote awareness of ADRs and the importance of reporting such events in order to increase patient safety. Again, newsletters, e-mails, in-services, grand rounds presentations, and other educations programs can be utilized to increase awareness of specific ADRs.

6. Establish mechanisms for screening ADRs continuously. These mechanisms should include retrospective reviews and concurrent monitoring, as well as prospective planning for high-risk groups. It is worthwhile to educate pharmacists to check for ADRs when they see orders for certain indicator drugs that are often used in treating an ADR (see Table 15–2), orders to discontinue or hold drugs, and orders to decrease the dose or frequency of a drug.42

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree