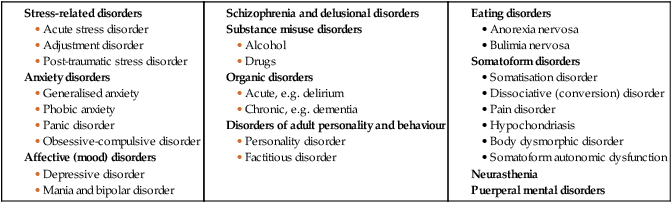

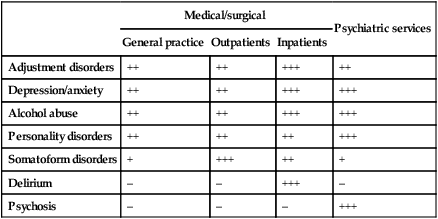

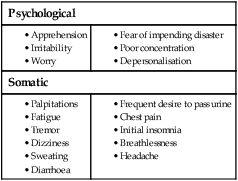

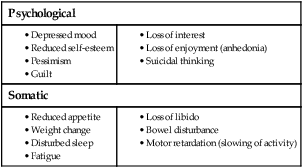

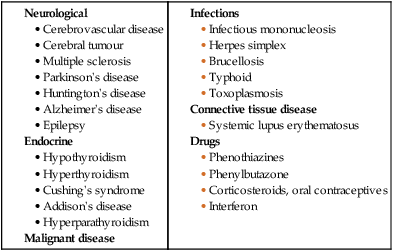

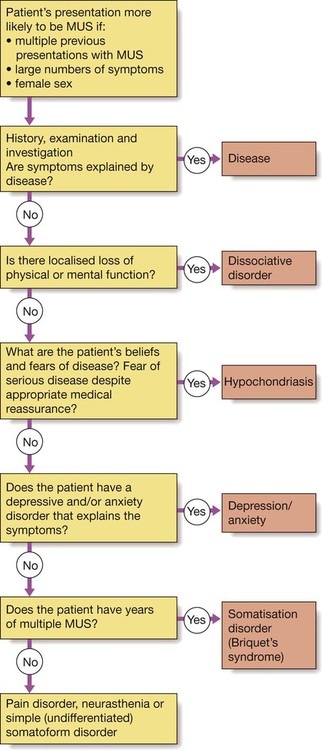

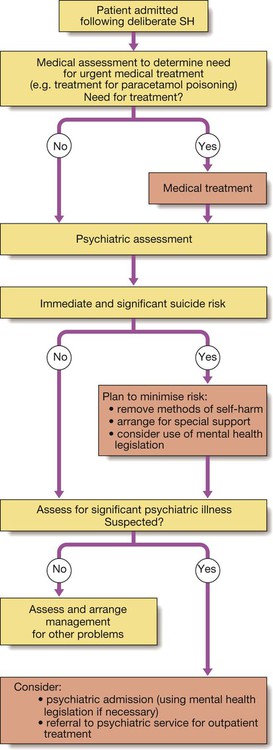

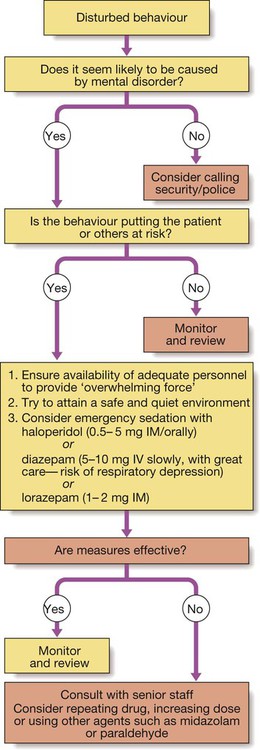

There are two main classifications of psychiatric disorders in current use: • the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (4th edition), or DSM-IV • the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Disease (10th edition), known as ICD-10. The two systems are similar; here we use the ICD-10 classification (Box 10.1). Psychiatric disorders are amongst the most common of all human illnesses. The relative frequency of each varies with the setting (Box 10.2). In the general population, depression, anxiety disorders and adjustment disorders are most common (10%) and psychosis is rare (1–2%); in acute medical wards of general hospitals, organic disorders such as delirium (20–30%) are prevalent; in specialist general psychiatric services, psychoses are the most common disorders. The aetiology of psychiatric disorders is multifactorial, with a combination of biological, psychological and social causes. Each of these factors may play a role in predisposing to, precipitating or perpetuating the disorder (Box 10.3). Psychiatric assessment differs from a standard medical assessment in the following ways: • There is greater emphasis on the history. • It includes a systematic examination of the patient’s thinking, emotion and behaviour (mental state). • It commonly includes the routine interviewing of an informant (usually a relative or friend who knows the patient), especially when the illness affects the patient’s ability to give an accurate history. Because of its greater complexity, a full psychiatric history (Box 10.4) and detailed mental state examination (MSE) may take an hour or more. However, a brief mental state examination, usually taking no more than a few minutes (see below), should be part of the assessment of all patients, not merely those deemed to be ‘psychiatric’. The form of thinking may also be abnormal. In schizophrenia, patients may display loosened associations between ideas, making it difficult to follow their train of thought. There may also be abnormalities of thought possession, when patients experience the intrusion of alien thoughts into their mind or the broadcasting of their own thoughts to other people (p. 247). • Memory. Registration of memories is tested by asking the patient to repeat simple new information, such as a name and address, immediately after hearing it. Short-term memory is assessed by asking him or her to repeat it after an interval of 1–2 minutes, during which time the patient’s attention should be diverted elsewhere. Long-term memory is assessed by gauging the recall of previous events. • Concentration. Serial 7s is a test in which the patient is asked to subtract 7 from 100 and then 7 from the answer, and so on. • Orientation. This is assessed by asking the patient about place – his or her exact location; time – what day, date, month and year it is now; and person – details of personal identity, such as name, date of birth, marital status and address. • Intellectual ability. This can be gauged from the history of the patient’s educational background and attainments but can also be assessed during the interview from the patient’s speech, vocabulary and grasp of the interviewer’s questions. Anxiety may be transient, persistent, episodic or limited to specific situations. The symptoms of anxiety are both psychological and somatic (Box 10.5). The differential diagnosis of anxiety is shown in Box 10.6. Most anxiety is part of a transient adjustment to stressful events: adjustment disorders (p. 242). Other more persistent forms of anxiety are described in detail on page 242. Anxiety may occasionally be a manifestation of a medical condition such as thyrotoxicosis (see Box 10.6). Depressive disorder is common, with a prevalence of approximately 5% in the general population. Depression is at least twice as common in the medically ill. It is important to note that depression has physical as well as mental symptoms (Box 10.7). The diagnosis of depression in the medically ill, who may have physical symptoms of disease, relies on detection of the core psychological symptoms of low mood and anhedonia. Depressive disorder must be differentiated from an adjustment disorder with depressed mood (p. 242). Adjustment disorders are common, self-limiting reactions to adversity, including physical illness, which are transient and require only general support. Depressive disorders (p. 243) are characterised by a more severe and persistent disturbance of mood and require specific treatment. In some cases, depression may occur as a result of a direct effect of a medical condition or its treatment on the brain, when it is referred to as an ‘organic mood disorder’ (Box 10.8). Depression is the major risk factor for suicide. Other risk factors are shown in Box 10.9. When depression is suspected, tactful enquiry should always be made into suicidal thoughts and plans. Asking about suicide does not increase the risk of it occurring, whereas failure to enquire denies the opportunity to prevent it. Elation, or euphoria, is the converse of depression and is characteristic of mania. It may manifest as infectious joviality, over-activity, lack of sleep and appetite, undue optimism, over-talkativeness, irritability, and recklessness in spending and sexual behaviour. When elated mood is severe, psychotic symptoms are often evident, such as delusions of grandeur (e.g. believing erroneously that one is royalty). Elevated mood is much less common than depressed mood, and in medical settings is often secondary to drug or alcohol misuse, an organic disorder or medical treatment. Where none of these applies, the patient may have a bipolar disorder (p. 244). Patients with MUS may receive a medical diagnosis of a so-called functional somatic syndrome, such as irritable bowel syndrome (Box 10.10), and may also merit a psychiatric diagnosis on the basis of the same symptoms. The most frequent psychiatric diagnoses associated with MUS are anxiety or depressive disorders. When these are absent, a diagnosis of somatoform disorder may be appropriate (Box 10.11). The main medical differential diagnosis for MUS is from symptoms of a medical disease. Diagnostic difficulties are most likely with unusual presentations of common diseases and with rare diseases. MUS are commonly an expression of depression and anxiety. A medical and psychiatric assessment should be completed in all cases (Fig. 10.1). Various types of delusion are identified on the basis of their content. They may be: • persecutory, such as a conviction that others are out to get me • hypochondriacal, such as an unfounded conviction that one has cancer • grandiose, such as a belief that one has special powers or status • nihilistic, e.g. ‘My head is missing’, ‘I have no body’, ‘I am dead’. Delusions should be differentiated from over-valued ideas, which are strongly held but not fixed. Where hallucinations and delusions arise within disturbed consciousness and impaired cognition, the diagnosis is usually an organic disorder, most commonly delirium and/or dementia (p. 244). This differential diagnosis is made by assessing the nature, extent and time course of any cognitive disturbances, and by investigating for underlying causes. Disturbed and aggressive behaviour is common in general hospitals, especially in emergency departments. Most behavioural disturbance arises not from medical or psychiatric illness, but from alcohol intoxication, reaction to the situation and personality characteristics. The key principles of management are, first, to establish control of the situation rapidly and thereby ensure the safety of the patient and others, and, second, to assess the cause of the disturbance in order to remedy it. Establishing control requires the presence of an adequate number of trained staff, an appropriate physical environment and sometimes sedation (Fig. 10.2). Hospital security staff and sometimes the assistance of the police may be required. In all cases, the staff approach is important; a calm, non-threatening manner expressing understanding of the patient’s concerns is often all that is required to defuse potential aggression (Box 10.12). If sedating drugs are required, antipsychotic drugs, such as haloperidol, and benzodiazepines, such as diazepam, are commonly used. The choice of drug, dose, route and rate of administration will depend on the patient’s age, sex and physical health, as well as the likely cause of the disturbed behaviour. The benefits of sedation must be balanced against the associated risks, however. Haloperidol can cause acute dystonias, including oculogyric crises, while the benzodiazepines can precipitate respiratory depression in patients with lung disease, and encephalopathy in those with liver disease. Thus, for a frail elderly woman with emphysema and delirium, sedation may be achieved with a low dose (0.5 mg) of oral haloperidol, while for a strong young man with an acute psychotic episode, at least 10 mg of intravenous diazepam and a similar dose of haloperidol may be needed. A parenterally administered anticholinergic agent, such as procyclidine, should be available to treat extrapyramidal effects arising from haloperidol, and flumazenil (p. 217) to reverse respiratory depression if large doses of benzodiazepines are used. • psychiatric, medical (especially neurological) and criminal history • current psychiatric and medical treatment • the time course and accompaniments of the current episode in terms of mood, belief and behaviour. Measures such as restraint, sedation, the investigation and treatment of medical problems, and psychiatric transfer all raise legal as well as medical issues (p. 257). In most countries, including the UK, common law confers upon doctors the right, and indeed the duty, to intervene against a patient’s wishes in cases of acute behavioural disturbance, if this is necessary to protect the patient or other people. Many countries, such as the UK, also have specific mental health legislation that may be used to detain patients. This is a vague term used to describe a range of primarily cognitive problems, including disturbances in perception, belief and behaviour. ‘Confusion’ usually presents as a problem when it becomes clear that the patient cannot comply with medical care; they may repeatedly wander off the ward, pull out essential cannulae and catheters, and hit nurses. The methods of assessment of cognitive function range from simple screening questions to detailed psychometric testing. All doctors should be able to undertake a brief cognitive assessment, as outlined above (p. 233). • organic disorders such as delirium, dementia, and focal deficits secondary to brain lesions • psychiatric disorders such as depressive pseudo-dementia and dissociative disorder Further investigation will usually be needed to identify the specific causes of any cognitive impairment identified (see Box 10.32, p. 250, and p. 209). Self-harm (SH) is a common reason for presentation to medical services. The term ‘attempted suicide’ is potentially misleading, as most such patients are not unequivocally trying to kill themselves. Most cases of SH involve overdose, of either prescribed or non-prescribed drugs (Ch. 9). Less common methods include asphyxiation, drowning, hanging, jumping from a height or in front of a moving vehicle, and the use of firearms. Methods that carry a high chance of being fatal are more likely to be associated with serious psychiatric disorder. Self-cutting is common and often repetitive, but rarely leads to contact with medical services. The incidence of SH varies over time and between countries. In the UK, the lifetime prevalence of suicidal ideation is 15% and that of acts of SH is 4%. SH is more common in women than men, and in young adults than the elderly. (In contrast, completed suicide is more common in men and the elderly (see Box 10.9).) There is a higher incidence of self-harm among lower socioeconomic groups, particularly those living in crowded, socially deprived urban areas. There is also an association with alcohol misuse, child abuse, unemployment and recently broken relationships. A thorough psychiatric and social assessment should be attempted in all cases (Fig. 10.3), although some patients will discharge themselves before this can take place. The need for psychiatric assessment should not, however, delay urgent medical or surgical treatment, and may need to be deferred until the patient is well enough for interview. The purpose of the psychiatric assessment is to: • establish the short-term risk of suicide • identify potentially treatable problems, whether medical, psychiatric or social. Topics to be covered when assessing a patient are listed in Box 10.14. The history should include events occurring immediately before and after the act, and especially any evidence of planning. The nature and severity of any current psychiatric symptoms must be assessed, along with the personal and social supports available to the patient outside hospital. Approximately 20% of SH patients make a repeat attempt during the following year and 1–2% kill themselves. Factors associated with suicide after an episode of SH are listed in Box 10.9. Misuse of alcohol is a major problem worldwide. It presents in a multitude of ways, which are discussed further on page 252 and in Box 10.35 (p. 253). In many cases, the link to alcohol will be all too obvious; in others, it may not be. Denial and concealment of alcohol intake are common. In the assessment of alcohol intake, the patient should be asked to describe a typical week’s drinking, quantified in terms of units of alcohol (1 unit contains approximately 8 g alcohol and is the equivalent of half a pint of beer, a single measure of spirits or a small glass of wine). Drinking becomes hazardous at levels above 21 units weekly for men and 14 units weekly for women. The history from the patient may need corroboration by the GP, earlier medical records and family members. The mean cell volume (MCV) and γ-glutamyl transferase (GGT) may be raised, but are abnormal in only half of problem drinkers; consequently, normal results on these tests do not exclude an alcohol problem. When abnormal, these measures may be helpful in challenging denial and monitoring treatment response. The prevention and management of alcohol-related problems are discussed on page 253.

Medical psychiatry

Classification of psychiatric disorders

Epidemiology of psychiatric disorders

Aetiology of psychiatric disorders

Diagnosing psychiatric disorders

Mental state examination

Thoughts

Cognitive function

Presenting problems in psychiatric illness

Anxiety symptoms

Depressed mood

Differential diagnosis

Suicide

Elated mood

Medically unexplained somatic symptoms

Differential diagnosis

Delusions and hallucinations

Delusions

Differential diagnosis

Disturbed and aggressive behaviour

Differential diagnosis

Confusion

Differential diagnosis

Self-harm

Initial management

Alcohol misuse

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Basicmedical Key

Fastest Basicmedical Insight Engine