72

CHAPTER OUTLINE

■ MEDICAL CONSEQUENCES OF ALCOHOL, TOBACCO, AND OTHER DRUG USE

■ COMMON MEDICAL PROBLEMS IN PERSONS WITH SUBSTANCE USE DISORDERS

■ CONSEQUENCES IN OLDER ADULTS

Persons with substance use disorders often do not receive regular health care. As a result, their medical care for acute and chronic conditions can be fragmented and inefficient. Furthermore, they may miss opportunities to receive preventive health care. In addition to the direct effects of intoxication, overdose, and withdrawal, abused substances can affect every body system. Substance use disorders are associated with behaviors that place individuals at risk of health consequences that are not directly related to use of the substance. Regular health care can lead to improved health for persons with addictive disorders. Such care could be accessed at general medical or specialty addiction treatment delivery sites. This section addresses the wide range of health consequences of alcohol and other drug use, focusing on the most common and most serious illnesses, by organ system, substance, and route of use. This introductory chapter reviews preventive care, addiction care during medical hospitalization, the medical consequences of substance use disorders, the management of common medical problems in persons with addictive disorders, and consequences in older adults. Preventive care for healthy adults and issues specific to persons with addictive disorders are presented herein because any health care contact is an opportunity for persons with addictive disorders to obtain routine preventive care. Subsequent chapters address the epidemiology, diagnosis, and management of consequences of substance use in detail, focusing on cardiac consequences; hepatitis, cirrhosis, and other liver diseases; renal and metabolic disorders; gastrointestinal consequences; respiratory disorders; neurologic complications; human immunodeficiency virus and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS); tuberculosis and other infectious diseases; sleep disorders; injury and trauma; endocrine and reproductive consequences; pregnancy; and management of surgical patients with substance use disorders.

ROUTINE AND PREVENTIVE CARE

In the 20th century, preventive health care meant a thorough and detailed evaluation focused on examination and testing. The “executive physical,” a “one-size-fits-all” approach in which more tests were better, evolved from this approach. Despite the fact that many in the general public, including physicians, tend to believe in extensive checkups “to make sure everything is OK,” over the past several decades, preventive care expert panels carefully evaluating scientific evidence have recommended targeted evaluations based on age and other risk factors (1). The rationale for these targeted evaluations is based on the notion that time and resources are limited and, perhaps more importantly, the recognition that preventive care can result not only in benefit but in harm (such as a perforated colon from a colonoscopy). In addition, some preventive testing predicted to offer health benefit has been shown to offer no benefit in terms of length and quality of life when evaluated in controlled clinical trials (e.g., screening chest radiographs in smokers) and to result in “overdiagnosis,” identification of conditions without clinical significance that must nonetheless be addressed (e.g., early-stage prostate cancer that would never manifest clinically). The approach presented here follows a targeted strategy based on the known effectiveness of interventions. Though disagreements exist among professional and other organizations (and their guidelines) regarding some details, most recommendations are in agreement when it comes to which diseases should be identified during their preclinical stages. Ongoing updates of recommendations by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) can be accessed at http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstfix.htm.

Medical History

The medical history in a person with substance use disorders should include the categories of assessment employed for all patients, such as any current complaints and the history of that present illness, allergies, systems review (including any symptoms of conditions that could be related to substance use), medications (including over-the-counter and alternative products), and then the past medical and surgical history. Questions regarding past history should address hospitalizations and any medical conditions (e.g., cardiovascular, pulmonary, hepatic, renal, or neurologic diseases and specific illnesses such as cellulitis, pneumonia, hepatitis) that might be related to substance use and might not be volunteered by the patient without direct questions asked by the physician. The social and family history is of particular importance. Queries should be made to understand the current living, work and financial situation, support system, travel history, and immigration status. In an asymptomatic person with an addictive disorder (in addition to a thorough alcohol and other drug use history), historical items relevant to preventive care become more of the focus. These assessments should include a review of sexual practices and behaviors, including condom use; dental care, including use of floss and brushing with fluoride toothpaste; diet (fat, cholesterol, fruit, grain, vegetable, carbohydrate, protein, and overall caloric intake); physical activity; calcium intake; use of lap and shoulder belts when in vehicles; use of helmets when riding a bicycle or motorcycle; presence of a firearm and smoke detector in the household; and cardiopulmonary resuscitation knowledge in the household. These assessments are recommended because they can lead to counseling interventions, depending on the answers. For persons with addictive disorders, screening for depression and anxiety, assessment of sexual practices, intention to conceive a child, and behavior that might lead to injury (including being alert for signs of interpersonal violence) are particularly important. Such patients should be asked specifically about substance use before operating a motor vehicle, riding with intoxicated drivers, heterosexual sex without contraception, and sex while intoxicated. In addition, a thorough history must include past immunizations or chemoprophylaxis (as for tuberculosis or to prevent folate deficiency). People with alcohol use disorders are at higher risk of folate deficiency, and this is of particular importance for women of childbearing age, whose fetuses are at risk of neural tube defects. Additional history is needed to determine if the patient belongs to a high-risk group that would indicate additional preventive interventions. For example, patients should be asked about chronic medical illnesses, whether they live in an institutional setting, contact with active cases of tuberculosis, recency of immigration, cardiovascular risk factors (smoking, cholesterol elevation, family history of heart disease, and diabetes), history or family history of cancer, travel patterns, receipt of blood products, drug injection, and occupation.

Physical Examination

The physical examination may be complete and should certainly address body systems related to any reported symptoms.

Vital Signs and Measurements

In asymptomatic persons, height, weight, and blood pressure assessments should be performed. The height and weight should be used to determine the body mass index and assess nutritional status.

Skin

Skin examination can reveal signs of injection drug use, the wrinkles associated with tobacco use, or the palmar erythema of a severe alcohol use disorder.

Head, Eyes, Ears, Nose, and Throat Examination

Examination should focus on the oral cavity: Smokers and heavy alcohol users should have a thorough examination of the oral cavity to look for premalignant and malignant lesions to which they are particularly susceptible, synergistically. Tobacco-stained teeth can serve as a focus for discussion. The oral examination may also find the extreme tooth decay associated with methamphetamine use due to xerostomia, tooth grinding, and poor hygiene.

Chest/Cardiovascular Examination

Particular attention should be paid to auscultation for cardiac murmurs that may be evidence of past valvular damage from injection drug use.

Abdominal Examination

Examination of the liver is advisable, if only to draw attention to the many possible complications of drug and alcohol use. Even asymptomatic persons can have the small hard liver of cirrhosis or the enlarged liver of chronic viral or alcohol-related hepatitis.

Breast Examination

Most preventive recommendations include the breast physical examination for adult women when done with mammography for screening, although the evidence for benefit is absent until age 40, when there is less risk from misidentification of benign lesions (1). Most masses detected in young women will be benign but may require investigation once detected to rule out malignancy. The risk of breast cancer is increased by even low drinking amounts (3 to 6 drinks per week) (2).

Male Genital Examination

Testicular examination for young men as well as rectal and prostate examinations (all to screen for cancers) are recommended by some specialty organizations though their value is uncertain at best (they miss most cancers and most abnormalities detected are not cancer). The risk of prostate and colorectal cancer may be increased by even low-risk amounts of alcohol consumption (3).

Female Genital Examination

Though a pelvic examination without testing (e.g., for cervical cancer) is not routinely indicated, addicted persons are at risk of sexually transmitted diseases, and genital warts, abnormal vaginal discharge, or herpetic lesions can be found.

Lymph Node Examination

Persons with alcohol, tobacco, and other drug use disorders should have the cervical, axillary, supraclavicular, and inguinal lymph node regions examined for lymphadenopathy. Tuberculosis, chancroid, syphilis, and HIV are more common in persons with addictive disorders who present with lymphadenopathy. Supraclavicular adenopathy can be the presenting sign of lung cancer in tobacco users.

Neurologic Examination

Brief cognitive assessments can be useful particularly in veterans, returning military personnel, and the elderly, in whom mild cognitive impairment or dementia or traumatic brain injury may need management and may be complicated by alcohol and other drugs of abuse.

Tests

Because people with substance use disorders are at risk for many medical illnesses, by various mechanisms, across organ systems and because some tests are widely available and relatively inexpensive, it is reasonable for all such patients to have a complete blood count, blood glucose, serum creatinine, liver enzymes, and urinalysis at least once. Injection drug users and those with HIV risk factors in particular should have a urinalysis and serum creatinine to assess the presence of renal disease.

Routine preventive care for all includes tests for cardiovascular risk. All men aged 35 years and older and women and younger adults at increased cardiovascular risk should be screened for hypercholesterolemia by testing serum total cholesterol and high-density lipoprotein. A fasting lipid profile could identify hypertriglyceridemia, which is associated with heavy drinking and can be a cause of pancreatitis. Primary prevention—identifying patients with hyperlipidemia who have no clinically evident coronary artery disease—can decrease the risk of heart disease and death. Hematologic testing for preventive purposes includes a hemoglobin, a mean corpuscular volume (MCV), or a hemoglobin electrophoresis, which should be checked in men and women who might be contemplating parenting. The purpose of the screen is to detect the common thalassemia traits and to provide genetic counseling. An unsuspected anemia or pancytopenia can be found in persons with an alcohol use disorder or HIV.

Sexually Transmitted Diseases

Adolescent and young adult women and others at high risk should have (urine) chlamydia testing performed. Persons with addictive disorders who have been sexually active or who use injection drugs should be screened routinely for sexually transmitted diseases with a serologic test for syphilis, HIV, and chlamydia (using the ligase chain reaction in a urine or cervical specimen). The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) recommends that all pregnant women, and all people presenting to health care settings aged 13 to 64 years, be tested for HIV on an optout basis with no special consent beyond that for routine medical care and with no specific requirement for preventive counseling and that HIV testing be done in high-risk patients yearly (4). Some state laws are incongruous with these recommendations. Because of the implications and the potential to trigger relapse, the timing of HIV testing must be individualized, with input from the patient, preferably to a time when recovery is stable. The serologic test for syphilis (rapid plasma reagin or Venereal Disease Research Laboratory) frequently is falsely positive in injection drug users (as is the serum rheumatoid factor and the partial thromboplastin time), reflecting a generalized activation of the immune system. As a result, the screening test should not be used as evidence of syphilis—instead, the result should be confirmed by a treponemal test such as the microhemagglutination test for Treponema pallidum or the fluorescent treponemal antibody tests.

Other Infectious Diseases

Among other risk factors, persons with alcohol and other drug use disorders without past known tuberculosis should be screened for asymptomatic infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis, using a 5-tuberculin-unit intradermal injection read at 48 hours (provided a previous test result is not known to have been positive). A positive test result in such persons is 10 mm of induration (5 mm if immune deficiency is present); in such cases, a chest radiograph should be performed. Interferon gamma release assays (IGRAs) (that measure release in response to antigens representing M. tuberculosis) done on blood samples can be used instead of skin testing. Because returning for a second visit is not required and because the tests may be more specific for tuberculosis infection, they have advantages for testing people unlikely to return for reading skin test results and for those who received bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccination. Provided the radiograph is not consistent with active tuberculosis, prophylactic pharmacotherapy should be considered regardless of age (5). Users of injection drugs, those with an alcohol use disorder, and persons with multiple sexual partners or high-risk sexual activity should have the international normalized ratio (INR), the serum bilirubin, the transaminases (aspartate aminotransferase [AST] and alanine aminotransferase [ALT]), and the serum albumin and alkaline phosphatase checked as screening tests for chronic hepatitis and cirrhosis (and the serum albumin for nutritional status). The serum prealbumin will give a more stable view of long-term nutritional status, as it fluctuates less than the serum albumin. Abnormal liver enzymes, INR, or serum bilirubin tests should be followed by hepatitis B (surface antigen and core antibody) and C antibody testing. The CDC recommends one-time testing regardless of risk factors for persons born during 1945 to 1965 (6) and testing for all with any history of injection drug use (regardless of liver enzyme levels). The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases recommends also testing all intranasal drug users who have shared paraphernalia. Previously hepatitis B–vaccinated individuals should have the anti-surface hepatitis B antibody determined to assess current immunoprotection. Injection drug users and those who practice anal intercourse and who are not from endemic areas should be tested for immunity to hepatitis A.

Cancer Screening

Smokers are at higher risk of cervical cancer. All women who have had sexual intercourse should have a cervical cytology (Papanicolaou smears) performed every 3 years starting at age 21 to detect the premalignant lesions of cervical cancer, stopping at age 65 unless prior screening has not been adequate or the woman is at high risk. Human papillomavirus (HPV) testing has become part of cervical cancer routine testing protocols for those between 30 and 65 years who wish to extend the screening interval to every 5 years.

Biennial mammography should be offered to women, from age 50 to 74. Screening prior to age 50 should be individualized based on patient preferences and values after discussing risks and benefits. Randomized trials show small benefit below the age of 50, and almost half of the women screened will suffer a false-positive and the consequences of further testing to clarify the diagnosis (7). Breast self-examination is of no proven benefit (8) and increases the risk of a benign breast biopsy. Mortality from breast cancer can be decreased by regular physical examination and screening mammography. A family history of breast cancer can indicate the need for earlier testing or referral to a specialist for genetic testing.

Prostate cancer screening remains controversial. The serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test is recommended by some specialty organizations, but many other groups (including all generalist physician organizations) do not. The USPSTF recommends against the use of the PSA for prostate cancer screening because many men are harmed by it and few, if any, benefit. If testing is done, patients should be informed about the potential benefits as well as the harms of false-positives and unnecessary treatments and their side effects (9). The controversy is due to the current state of the science: Prostate cancer usually has a very long preclinical phase, it is not yet possible to predict accurately which cases will progress, the testing is neither sensitive nor specific, the evaluation for a positive test is invasive, and the treatment results in significant complications (including erectile dysfunction and incontinence). Only one study (of radical prostatectomy) has shown a decrease in cancer-related mortality (10). In that study, only a small fraction of the tumors were PSA detected. The Prostate Cancer Intervention Versus Observation Trial (PIVOT) study in the United States found no benefit of prostatectomy for screen-identified cancer on all-cause or prostate cancer–specific mortality (11). Patients who choose to be screened might do so because of the belief they will benefit, a belief shared by some physicians and scientists who find the trials inadequate due to contamination of control groups with PSA testing and inability to detect very small effects. Those who believe in and choose to go ahead with screening may consider risk of prostate cancer, which is higher among African Americans and those with a family history of the disease, as reason to begin screening, at age 40.

Colorectal cancer screening is not controversial. Colorectal cancer mortality can be decreased in adults aged 50 years and older (younger for those with risk factors or familial disease) by a variety of approaches. Screening is not recommended after age 85 and is of uncertain benefit between 76 and 85 years of age. Currently recommended approaches include yearly fecal occult blood testing, flexible sigmoidoscopy every 5 years, and both procedures or colonoscopy every 10 years. Positive occult blood testing or sigmoidoscopy should be followed by an examination of the complete colon.

Testing for Other Conditions

Older adults (aged 65 or older) should have thyroid function testing (serum thyroid-stimulating hormone) because abnormalities are common, difficult to recognize clinically, and easily treatable. Vision and hearing testing should be performed routinely in older adults. Bone mineral density (BMD) testing by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry or quantitative ultrasonography of the calcaneus should be done in women aged 65 and older or in women with similar risk (e.g., a 55-year-old with parental fracture history or a 50-year-old with smoking, daily alcohol use, and parental fracture history) that can be determined using a freely available online risk calculator (http://www.shef.ac.uk/FRAX/). Evidence is insufficient to make a recommendation for average-risk men. Persons with substance use disorders can have poor diets, little sun exposure, and minimal intake of milk products; screening for vitamin D deficiency with a 25-hydroxyvitamin D should be considered.

Preventive Counseling

All patients should be counseled about healthy dietary habits (limiting saturated fat and favoring fruits, vegetables, legumes, fiber, and grains) and physical activity (at least 20 minutes of aerobic exercise three times a week). All with alcohol and other drug use disorders should be counseled about safer sexual practices (abstinence and condom use), and injection drug users should be educated about sterile injection practices. Women of childbearing age and their partners should be counseled about contraceptive options. All persons should be counseled that, in addition to their addiction specialty care, they should engage in regular primary and preventive health care with a primary care physician. Linkage of patients to primary medical care and/ or integration of medical and addiction care has many potential benefits, including improved prevention, management of chronic conditions, coordination of the many health care services needed by patients with addictive disorders, and support in relapse prevention efforts (12). In addition, because psychiatric illness is so common in addicted patients, linkage to mental health care should be offered when appropriate. This linkage can be accomplished through a primary care physician. Those persons who store or carry weapons should be reminded of gun safety. All patients should be advised about seat belt and helmet use. Referrals for both regular eye and dental care should be routine. Preventive advice about safe lifting is warranted to prevent low back injury.

Immunizations

Immunizations for adults include tetanus toxoid every 10 years. (TDaP) vaccine should be given once when a tetanus booster is due or prior to having close contact with a baby or work as a health care professional (the reason for these latter indications is for prevention of pertussis). TDaP may be repeated once as a booster after age 65. Tetanus toxoid is particularly important for injection drug users, who can expose themselves to tetanus. Detailed recommendations are published by the CDC at http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/hcp/index.html. Hepatitis B vaccination (a series of three injections) is indicated for injection drug users, health care workers, persons with hepatitis C, sexually active individuals who are not involved in long-term monogamous relationships, and any adult seeking protection from infection. Hepatitis A vaccination (two injections) is indicated for travelers, those with any chronic liver disease, those who practice anal intercourse, and injection drug users, when negative for immunity (immunoglobulin G to hepatitis A). Pneumococcal vaccination should be administered to all persons aged 65 years and older and those with chronic cardiopulmonary disease (including heart disease, more common in smokers, and reactive airway diseases such as obstructive lung disease and asthma, which are more common in smokers and users of inhaled drugs). Alcoholism is a specific recognized indication for the vaccine, and many practitioners believe other drug addiction also is a reasonable indication. Other indicated vaccines include varicella vaccine for all adults without immunity; zoster vaccine for all older people (aged 60 or older), regardless of prior episodes of herpes zoster; and HPV vaccine for all young women (ages 11 to 26) and young men up to age 21 and to age 26 if they have sex with men. Military recruits and those with asplenia should receive meningococcal vaccination.

When childhood vaccinations are unknown, consideration should be given to a primary series for polio; measles, mumps, and rubella; and varicella vaccination. Many adults will have immunity to these diseases, but, if unknown, testing is warranted, given that many persons with addictive disorders may be in group living situations, sometimes with children and young adults, in which measles and varicella infections can spread easily. Influenza vaccination should be given yearly to all persons with addictive disorders. It is particularly indicated for those with cardiopulmonary disease and older adults but is cost-effective for general populations, too, and of particular utility for those living in group settings.

Chemoprophylaxis

Aspirin is recommended for the prevention of myocardial infarction in men ages 45 to 79 and for the prevention of ischemic stroke in women ages 55 to 79 when the benefit outweighs the risk of gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Trials find benefit for dosages of 75 and 100 mg daily and 100 and 325 mg every other day. A dosage of approximately 75 mg/d is as effective as higher dosages. Hemorrhage risk is elevated among older people, men, and those with upper gastrointestinal tract pain, gastrointestinal ulcers, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) use. Clinical conditions associated with substance use disorders such as end-stage liver disease and alcoholic gastritis would also clearly increase the risk. USPSTF recommendation statements provide figures and links to resources to calculate cardiovascular risks (http://hp2010.nhlbihin.net/atpiii/calculator.asp and http://www.westernstroke.org/PersonalStrokeRisk1.xls) and estimate for whom the benefits may outweigh the risks. The benefit of aspirin may not outweigh the risks of serious central nervous system or gastrointestinal bleeding in people with alcohol use disorders without symptoms (or high risk of) of coronary disease because they are at risk of gastritis, thrombocytopenia, coagulopathy, and trauma.

Women of childbearing age should take folate 0.4 to 0.8 mg daily to prevent neural tube defects. Because of the risk of thiamine, vitamin D, pyridoxine, niacin, riboflavin, zinc, and folic acid deficiency in people with alcohol use disorders and those with deficient diets, a daily multivitamin including 400-IU vitamin D, 100-mg thiamine, and 1-mg folic acid can be recommended. If serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D is low (<30 ng/mL), repletion should begin with 50,000-IU vitamin D weekly for 4 to 8 weeks. Because magnesium deficiency is common in people with alcohol use disorders, replacement by encouraging the use of foods with high magnesium content (such as peanuts) or a magnesium supplement (magnesium oxide tablets or magnesium hydroxide–containing antacids) is recommended. If the INR is known to be elevated, a trial of vitamin K is warranted, though generally the INR elevation in addicted persons will be due to liver disease and not to vitamin deficiency.

Men and women, particularly those with deficient diets, should ensure adequate calcium intake in their diets or should use supplements (1-g elemental calcium daily for all but postmenopausal women, who should receive 1.5 g). Bisphosphonates and raloxifene may be used for the prevention of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women, though the risks and benefits for addicted persons are difficult to predict. Risks for osteoporosis are higher in people with alcohol use disorders and some other addicted persons, but the interaction between estrogens and estrogen receptor modulators and alcohol on breast cancer is not clear, and the side effects of the drugs in people who drink heavily and those with liver disease are not well characterized. All adults with inadequate intake should be advised to take supplemental calcium and vitamin D (amounts vary by age and gender).

One form of chemoprophylaxis not usually considered is to prescribe intranasal or intramuscular naloxone to people with opioid dependence and their significant others to prevent overdose (the latter is less costly and the more common choice at community-based programs; the former, though higher cost, is gaining popularity in part because it does not require a needle). Evidence is growing that suggests people can be rescued from serious overdoses (13,14). In addition to prescription of naloxone, patients and their significant others are educated regarding how to use the medication and to call for emergency services.

CARE DURING HOSPITALIZATION

Because of the burden of illness carried by persons with substance use disorders, they can require transfer from addiction treatment to a general hospital, or they can be admitted there directly. During a medical hospitalization, three areas deserve particular attention: management of substance withdrawal, pain management, and common comorbidities (15). Treatment (including brief interventions, which are well suited to medical hospital settings) and withdrawal and pain management are addressed elsewhere in this textbook, but several points are relevant to medical hospitalizations specifically.

Withdrawal

When a history of alcohol use disorder and recent regular heavy use is obtained, withdrawal should be anticipated. Symptoms should be treated as they appear. Persons not yet symptomatic with withdrawal but with past alcohol-related seizures or concomitant acute medical or surgical conditions (which increase the risk of withdrawal) should be treated with a benzodiazepine (i.e., 10- to 20-mg diazepam or 1- to 2-mg lorazepam to prevent convulsions or delirium) (16). Because the symptoms of withdrawal may not be distinguishable from systemic symptoms of infection, heart disease, or neurologic conditions, treatment for withdrawal should proceed while investigations to identify other treatable medical disorders continue. Though the use of standardized withdrawal scales generally is encouraged, their lack of specificity requires that the information they provide be considered in the context of the coexisting medical illness. Nevertheless, patients hospitalized for withdrawal as well as for other medical conditions have had favorable outcomes when treated with symptom-triggered therapy. Similarly, opioid and other drug withdrawal should be identified and managed pharmacologically. Patients who already are in treatment for opioid or long-acting sedative dependence should have their treating clinician contacted when they are hospitalized, so that any prescribed ongoing treatment can be continued. Similarly, addiction treatment providers should communicate directly with hospital physicians to facilitate appropriate treatment, after obtaining permission from the patient. Doses for patients not on long-acting opioid treatment should be adequate to prevent withdrawal and should be administered to allow treatment of the underlying medical disorder (i.e., 10- to 20-mg methadone, repeated in 2 hours and then given daily or in divided doses twice a day). At hospital admission, when deciding on the best treatment for the patient, the patient’s disposition at discharge should be anticipated. If the patient plans to abstain from the substance at hospital discharge, the opioid can be tapered if symptoms allow. Alternatively, a dose sufficient to avoid withdrawal can be maintained during the hospitalization for those who intend to continue drug use or to enter a maintenance treatment program. In addition to providing comfort and helping to prevent the more serious complications of withdrawal (such as convulsions from alcohol withdrawal), specific treatment of withdrawal controls the autonomic symptoms that can worsen a patient’s medical condition (such as tachycardia during a myocardial infarction) and helps the patient cooperate with treatment for the medical condition that prompted hospitalization.

Another consideration for the management of withdrawal in hospitalized patients is the route of administration of the drug. Delirious patients should receive intravenous medications (such as diazepam or lorazepam), whereas others who cannot take medications by mouth should receive medications via a route associated with reliable absorption for the particular drug: lorazepam intramuscularly for alcohol withdrawal or methadone (40% to 50% of the oral dose in three to four divided doses) intramuscularly for opioid dependence.

Pain

Pain management often becomes an issue during medical hospitalization of patients with substance use disorders. Physicians and nurses may fear providing pain control with opioids when a patient is addicted to them, because of the fear of causing or worsening addiction. This management style generally results in inadequate pain management and frustration for patient and provider alike. Clearly, patients with substance use disorders usually are very tolerant to the substance they use.

In the case of opioid dependence, pain control can be achieved only with substantially higher doses of opioids, with careful reassessment of the dose effect and timing to make appropriate adjustments. Once a dose is determined, pain medications should be given on a regular schedule rather than as needed, to avoid making the patient demand medication to relieve uncontrolled symptoms. Similar principles apply for patients on opioid agonist treatment (17).

Comorbidities

Finally, while patients are hospitalized, several comorbidities should be considered. First, because psychiatric comorbidity is common (in particular, antisocial personality disorder, anxiety, and depression), attention to behavioral issues is important. Hospital staff members should take extra care to explain hospital procedures, while setting firm limits. Patients should be assured that their medical, psychiatric, and addiction-related symptoms and pain will be attended to. Discussing withdrawal and pain treatment regimens with the patient can help avoid later problems and disagreements and help allay the fears and preconceptions patients may have about providers. Screening for coexisting medical disorders (such as HIV, hepatitis, and tuberculosis) during a medical hospitalization should be considered because the acute care setting may provide the only medical care received by the patient. Nevertheless, when such testing is done, consideration should be given to the patient’s readiness to hear and handle the results and to arranging follow-up medical care for the condition. Most patients in detoxification centers believe HIV testing should be available during detoxification (18). Treatment for coexisting medical and psychiatric conditions should be made available.

MEDICAL CONSEQUENCES OF ALCOHOL, TOBACCO, AND OTHER DRUG USE

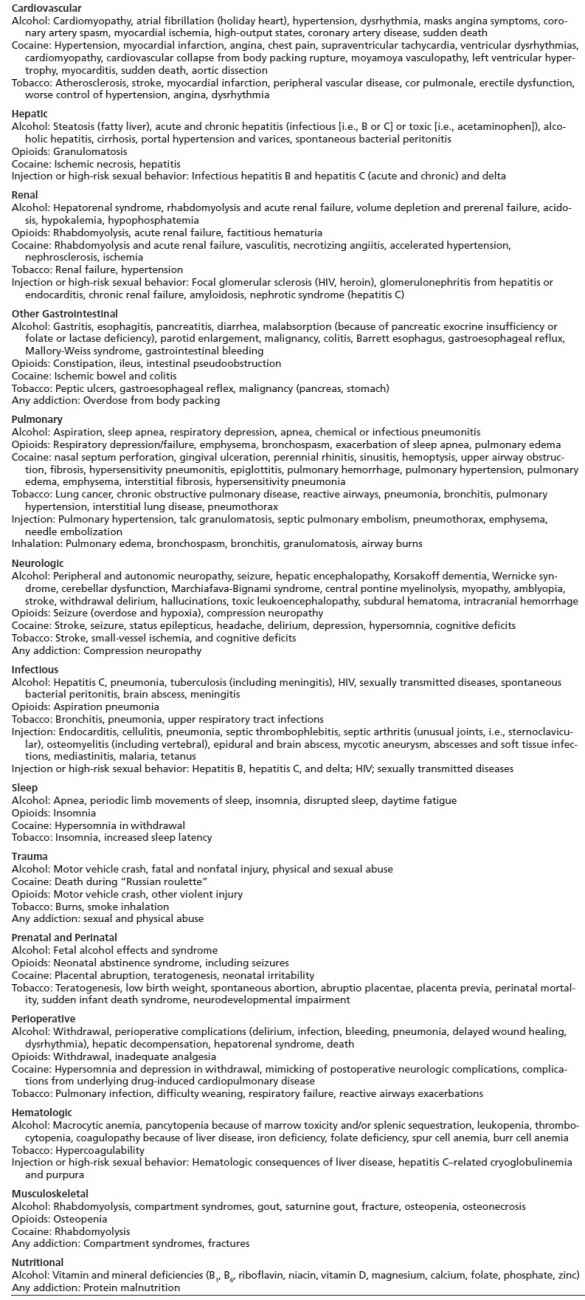

Medical consequences of addiction may be due to drug-specific effects, methods of administration, contaminants in or vehicles for drugs used, behavioral habits associated with substance use, or common comorbidities (Table 72-1). In this portion of the chapter, the medical consequences of addiction are reviewed and organized by drug and then by organ system or clinical area. More details can be found in the chapters in this section. Though some lifestyle choices and risk behaviors span more than one substance, consequences are discussed once to avoid redundancy.

TABLE 72-1 SELECTED MEDICAL DISORDERS RELATED TO ALCOHOL AND OTHER DRUG USE

Alcohol

The medical consequences of alcohol use are seen in almost every organ system of the body. Women are more susceptible to many of the effects at lower doses because of less first-pass metabolism of alcohol and lower body weights on average. Though low-risk drinking may have some beneficial effects for selected individuals, 2 drinks per day for women and 3 drinks per day for men increase the risk of death (19).

Cardiovascular Consequences

In addition to the transient hypertension seen during withdrawal, heavy drinking (about 2 or more standard drinks per day) is associated with chronic hypertension, which can lead to end-organ cardiac, retinal, renal, and vascular damage (20). Hypertension can be the result of even low levels of regular consumption. Though persons who in retrospect prove to be drinkers of low-risk amounts appear to have a lower incidence of coronary heart disease events, chronic heavy drinking can lead to alcoholic cardiomyopathy and congestive heart failure. Echocardiogram reveals diffuse hypokinesis and often four-chamber dilation. If left ventricular thrombosis is seen, patients are at higher risk of embolic stroke. Treatment consists of alcohol abstinence (which can, in some cases, lead to an increase in the left ventricular ejection fraction) and standard treatments for congestive heart failure (which include angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or antagonists, furosemide or other loop diuretics, nitrates, and sometimes digoxin). Evaluation for sustained ventricular dysrhythmias in symptomatic patients is warranted and may lead to anti-arrhythmic therapy (e.g., with amiodarone) or implantation of an automatic implantable cardioverter–defibrillator to decrease the risk of sudden death. Anticoagulation with warfarin may be indicated when there is a ventricular thrombosis, but the risk–benefit balance often is unclear, particularly when the patient is not abstinent.

Atrial fibrillation (“holiday heart”) can occur as a consequence of alcohol use or withdrawal, is not restricted to holidays, and usually resolves spontaneously. If the dysrhythmia persists after treatment for withdrawal (with benzodiazepines and, in this case, beta-blockers or calcium channel blockers) and abstinence, other etiologies (e.g., hyperthyroidism, hypertension, ischemic heart disease, and cardiomyopathy) should be evaluated, and additional treatment (electrical or chemical cardioversion and anticoagulation) should be considered. Low-risk drinking (e.g., fewer than 2 standard drinks per day) has been associated with fewer cardiovascular events and decreased mortality in men (but not in average-risk women) (21), although no randomized trials studying important clinical outcomes (e.g., myocardial infarction, mortality) have been done of this pharmacologic agent, a carcinogen with known side effects. Furthermore, heavy episodic drinking amounts have adverse cardiovascular consequences (22). The epidemiologic findings of benefit for moderate drinking can be confounded by alternative explanations, such as differences in social characteristics that remain unaccounted for (23). Studies have suggested that, if there is a benefit, it may be most pronounced in patients who have the same alcohol dehydrogenase genotype that may predispose them to alcohol dependence (24). Clearly, nondrinkers should not begin to drink for cardiovascular benefit. Further details may be found in Chapter 73.

Liver Disorders

Hepatitis ranges in severity from an asymptomatic elevation of the hepatic transaminases to critical illness with hepatic failure. In alcoholic hepatitis, AST usually is higher than ALT. A higher ALT concentration suggests another or a concomitant etiology, such as hepatitis C, for which alcohol abuse is a risk factor. Heavy alcohol use accelerates the progression to cirrhosis in hepatitis C and interferes with the success of treatment. Hepatic steatosis can cause elevations in serum transaminases, and it can be related to alcohol use or not. Though steatohepatitis is best diagnosed by liver biopsy, clinically, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis is often diagnosed when serology for hepatitis B and hepatitis C is negative, the abnormality persists with abstinence, and an ultrasound examination is consistent with the diagnosis.

Classic alcoholic hepatitis presents with fever, leukocytosis, right upper quadrant pain and tenderness, and elevations of the AST concentration out of proportion to ALT elevations. Management consists of abstinence from alcohol as well as supportive care, with attention to fluid and electrolyte balance, vitamin K for coagulopathy, clotting factor replacement when there is active bleeding and coagulopathy, and attention to volume and mental status. Patients with coagulopathy, hyperbilirubinemia, and hepatic encephalopathy are at high risk of death. Corticosteroids have been shown to decrease mortality in selected severe cases of alcoholic hepatitis (hepatic encephalopathy or when 4.6 times the prothrombin time above control in seconds plus the bilirubin is greater than 32) (25). In general, before giving steroids (prednisolone 40 mg a day for 4 weeks followed by a taper), active infection should be excluded. In addition, efficacy is not known for patients with concomitant pancreatitis, gastrointestinal bleeding, or renal failure. Propylthiouracil, colchicine, oxandrolone, and pentoxifylline have shown promising results in some studies (even for mortality in the case of the latter two), though because of limited and conflicting data to date, they are not yet standard treatments.

Cirrhosis can develop in chronic alcohol users either as a consequence of hepatitis C, recurrent alcoholic hepatitis, or, simply, chronic heavy use. An increase in the incidence of cirrhosis can be detected in populations drinking 2 to 3 standard drinks per day compared with nondrinkers (19,21), though heavier amounts are more commonly associated with the condition (i.e., 40 to 60 g/d of ethanol for men and less [20 g] for women) (26). Cirrhosis leads to hypoalbuminemia, coagulopathy, and hyperbilirubinemia. Hepatocellular carcinoma can occur, particularly when hepatitis C is present. Some recommend screening by ultrasound and/or serum alpha-fetoprotein though others have suggested the incidence is not high enough to justify it and studies to date suggest the strategy would not decrease mortality. On the other hand, it can be cured surgically if detected early enough. Complications of cirrhosis portend a poor prognosis. These complications include hepatic encephalopathy, esophageal or gastric variceal bleeding, ascites and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, volume overload and edema, and hepatorenal syndrome. When cirrhosis and alcoholic hepatitis coexist, the prognosis is poor (35% to 50% for 4- to 5-year survival), particularly when drinking continues. End-stage liver disease of many etiologies can be addressed with liver transplantation. Patients transplanted because of alcoholic liver disease have similar survival to those transplanted for other causes of liver failure (27). Many liver transplantation programs have required defined periods of abstinence—often 3 to 12 months— before patients will be evaluated for this extensive surgery and scarce resource, though assessing relapse risk without requiring an arbitrary period of abstinence is an alternative approach (28). Furthermore, most transplant recipients do not return to drinking (22% in the 1st year), and few return to heavy drinking (5% to frequent heavy use in 1 year, 20% at 5 years) (29). There are few predictors of relapse (other drug use, having needed alcohol rehabilitation, depression, length of pretransplant sobriety, and having a family history of alcohol dependence) (29). Chronic alcohol use increases the risk of acetaminophen toxicity, even at doses of 4 g daily, particularly when the patient has been fasting; cases of fulminant hepatic failure have been reported (30). Further details may be found in Chapter 74.

Renal and Metabolic Consequences

Renal and metabolic consequences of alcohol use often are seen in acute care settings. Hepatitis C can lead to nephrotic syndrome and glomerulonephritis with or without cryoglobulinemia and purpura. Cirrhosis can be complicated by the almost always fatal renal ischemic disorder, hepatorenal syndrome. Chronic renal insufficiency may be seen in persons who ingest home-distilled alcohol made with lead equipment. Acute renal failure from rhabdomyolysis can occur after alcohol intoxication. Fluid and electrolyte abnormalities are very common and often are minimized and overlooked in people with heavy alcohol use who present for medical care. Many patients with heavy alcohol use who present for medical treatment will be volume depleted from vomiting, diarrhea, and diuresis. Volume repletion is best accomplished orally, when possible, and with intravenous normal saline, at least until the patient no longer manifests postural changes in blood pressure and heart rate and excess losses are not continuing. Acidosis can be a medical emergency. The first step is to distinguish between a non-anion gap and an anion gap acidosis. If an anion gap is not present, diarrhea is the most common cause in people with heavy alcohol use. If an anion gap is present, the differential diagnosis is broad, but, in the people with heavy alcohol use, lactic acidosis (from sepsis, injury, severe pancreatitis, or after convulsion), ketoacidosis, and ingestion should be considered first. To rule out ingestion, in addition to the history (which may be unreliable), the measured serum osmolality should be compared with the calculated osmolality (accounting for the serum ethanol in the calculation). If no osmolar gap is present, ethylene glycol and methanol ingestions are unlikely. If a gap is present, testing for these ingestions should be done though levels are usually not available in time to assist with acute management. These ingestions require prompt treatment with fomepizole, hemodialysis, or both to prevent blindness or death.

Alcoholic ketoacidosis can also occur in people with alcohol use disorders. The glucose concentration can be high, normal, or low, and the urine ketones can be negative (although serum ketones should be positive). The treatment is volume expansion, and the substrate is given as 5% dextrose in normal saline (preceded by thiamine). In the absence of ketones or an osmolar gap, lactic acidosis is the next most serious diagnosis to consider, mainly because it can be the only clue to an unrecognized etiology (such as myocardial infarction or recent convulsion).

Alkalemia is not uncommon in people with heavy alcohol use, either from respiratory alkalosis related to liver disease and hyperventilation or metabolic alkalosis from vomiting. Treatment for withdrawal (holding diuretics if the patient is on them, control of vomiting with antiemetics, and abstinence from alcohol, combined with volume repletion) can help speed the resolution of the alkalemia, which is important because alkalemia can be associated with hypokalemia and hypomagnesemia from secondary hyperaldosteronism. When dextrose is given to malnourished people with heavy alcohol use, severe hypophosphatemia can be unmasked and require treatment. Hypomagnesemia is common in people with heavy alcohol use, as a result of diuretic use, hypokalemia, and reversible hypoparathyroidism resulting from impaired parathyroid hormone release when the magnesium cofactor is deficient. The latter condition also leads to hypocalcemia, which does not respond to calcium replacement; rather, it responds to magnesium repletion. The hypokalemia often seen in people with heavy alcohol use with hyper-aldosteronism from volume depletion and diuretic use will not correct until magnesium is replaced. Serum levels do not reflect total body magnesium stores, so empiric replacement is the best approach. Oral replacement of magnesium and phosphate is possible with magnesium-containing antacids and milk, but this approach often is limited by an inability to take food by mouth or by diarrhea (which worsens the deficiencies). Intravenous replacement, with cardiac monitoring in the case of severe hypophosphatemia, may be necessary. Hyperglycemia or hypoglycemia can be seen in people with alcohol use disorders as a result of pancreatic insufficiency or, in the case of end-stage cirrhosis, as a result of depleted glycogen stores, which is a very poor prognostic sign. Further details may be found in Chapter 75.

Gastrointestinal Consequences

Gastrointestinal problems are very common in the patient with moderate to severe alcohol use disorder. Alcohol is directly toxic to the gastric mucosa and can lead to gastritis. Gastritis can be asymptomatic or can present as epigastric burning, nausea, vomiting, anemia, or hematemesis (coffee-grounds emesis). Vomiting can lead to a Mallory-Weiss tear and hematemesis. Alcohol can lead to stomatitis, esophagitis, duodenitis, esophageal cancer, and gastric cancer. Endoscopy is warranted for persistent reflux symptoms or epigastric pain, particularly if weight loss is present or if patients are aged 40 years and older. Liver and pancreatic consequences of alcohol use are among the most well known. Pancreatitis often presents as epigastric pain, sometimes radiating to the back, in chronic heavy alcohol users. The other common cause in the United States is gallstones. The serum amylase often is elevated unless there has been chronic pancreatic damage. The amylase is neither sensitive nor specific for pancreatitis. In people with moderate to severe alcohol use disorder, amylase often is elevated because of chronic parotitis. Abdominal computed tomography is the most sensitive and specific test, but it is not indicated unless the presentation is atypical, fever is present, or the patient does not improve as expected. Severity can range from mild epigastric pain after eating, with some nausea, to a mortal condition complicated by acidosis, adult respiratory distress syndrome, and hypovolemia. Predictors of death include hyperglycemia, anemia, hypoxemia, acidosis, older age, leukocytosis, elevated blood urea nitrogen, lactate dehydrogenase or AST, hypocalcemia, or hypovolemia (31). The only treatment proven to decrease mortality is volume repletion, best accomplished with intravenous normal saline (32). Standard therapy includes nothing by mouth, volume repletion, and pain control by using opiates parenterally. Antibiotics should be considered in the presence of unexplained fever. Surgical consultation should be obtained when other diagnoses are being considered and when consideration is given to necrotizing pancreatitis. When acute episodes resolve, a return to drinking can lead to recurrent episodes and ultimately to constant pain and chronic pancreatitis, loss of pancreatic exocrine function with greasy stools and malabsorption, and even loss of pancreatic endocrine function manifested by hyperglycemia and diabetes. The prognosis is markedly worse with any ongoing alcohol consumption. Oral pancreatic enzyme supplementation with meals then is indicated, although pain management is difficult and often requires opioids. Serum amylase and lipase often are normal, although calcifications may be seen on abdominal radiographs. Further details may be found in Chapter 76.

Respiratory Consequences

Alcohol intoxication can lead to respiratory depression and aspiration, leading to a chemical or infectious pneumonia. Tachypnea can be the result of pulmonary infection, respiratory alkalosis of liver disease, alcohol withdrawal, or compensation for a metabolic acidosis. Further details may be found in Chapter 77.

Neurologic Consequences

Neurologic complications are perhaps some of the most well known. Alcohol intoxication can lead to head trauma. The signs and symptoms of intracranial hemorrhage—particularly subdural hematoma—can be confused with intoxication. Imaging of the brain is indicated when there are signs of significant head trauma and abnormal mental status, focal neurologic deficits are present, or when neurologic symptoms do not resolve with declining alcohol levels. People with alcohol use disorder are at higher risk of tuberculosis, which can manifest as tuberculous meningitis. Delirium tremens (DTs) are the diagnosis of exclusion (by lumbar puncture) when fever and delirium are present in a person with moderate to severe alcohol use disorder. In addition to withdrawal seizures, alcohol can lower the seizure threshold in epileptics, and seizures may be the presenting sign of an intracranial hemorrhage. Low-risk drinking may decrease the risk for ischemic stroke (33), but heavy drinking (even at 1 to 2 or more drinks a day) (34) increases the risk for ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke, related to an interplay with smoking, trauma, hypertension, folic acid deficiency and hyperhomocysteinemia, and cardiomyopathy (35). The overall risk of stroke in women is increased in those who consume just more than 1 standard drink per day (36).

Cognitive impairment may be caused acutely by Wernicke-Korsakoff disease because of thiamine deficiency, presenting with confusion, ataxia, or nystagmus. Parenteral thiamine, 100 mg administered before glucose, is the initial treatment. Chronically, Wernicke-Korsakoff disease can develop into Korsakoff syndrome, a memory impairment classically characterized by confabulation. More commonly, chronic alcohol use disorder is associated with a nonspecific dementia and volume loss on head computed tomography. Toxic leukoencephalopathy, or damage of cerebral white matter, can contribute to the dementia seen with alcohol dependence (37). Marchiafava-Bignami disease, caused by lesions in the corpus callosum, is rare. Also rare is central pontine myelinolysis, which is seen in conjunction with alcohol use disorder and too rapid correction of hyponatremia. Alcoholic cerebellar dysfunction is not so rare; it results in ataxia and incoordination and often is irreversible. People with alcohol use disorder can suffer from peripheral neuropathy, usually from vitamin deficiency, pressure on a nerve, or ethanol toxicity. The classic presentation of alcoholic poly-neuropathy is of sensory disturbance, including burning, pain, and numbness in a stocking–glove distribution.

Withdrawal, seizures, and DTs are major and well-known neurologic consequences of moderate to severe alcohol use disorder. Though these direct medical consequences of alcohol withdrawal (hyperautonomic states, seizures, and delirium) are covered in detail elsewhere in this book, mention is made here because they are common, often are managed in acute care general medical hospitals, and can lead to death. Many patients in withdrawal can be managed as outpatients with or without medication, provided symptoms are minimal and there is little comorbidity that would complicate outpatient management or place patients at higher risk of complications of withdrawal. Alcohol withdrawal symptoms, such as diaphoresis and tremor, begin 6 to 48 hours after the last drink (38). Such withdrawal symptoms may resolve spontaneously or require treatment with benzodiazepines. Benzodiazepines are the only medications proven, compared with placebo, to ameliorate symptoms of withdrawal, to decrease the risk of seizures and delirium, and, compared with paraldehyde (39), to speed achievement of a calm but awake state in patients experiencing delirium (16,38). Signs found on physical examination include tremor, moist warm skin, agitation, tachycardia, or hypertension, though these signs may be absent. The tachycardia can complicate underlying medical conditions such as coronary artery disease by precipitating angina or myocardial infarction.

Pharmacologic treatment is indicated for asymptomatic patients at higher risk of complications (acute medical, surgical, or psychiatric comorbidity; past seizures; and past delirium) and for those with significant symptoms (on the Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol, Revised, a score of more than 8 to 15) to prevent progression to seizures or delirium and for patient comfort (16). Seizures, when they occur, almost always resolve spontaneously. They can recur and generally do so within 6 hours of the first seizure. Benzodiazepines prevent further seizures and progression to DTs. Phenytoin and other anticonvulsants are not indicated unless there is another cause or suspected cause for the seizures in addition to alcohol. DTs (hyperautonomia and disorientation/confusion) should be managed in a setting where frequent and intensive monitoring is possible because of the risk of death from the condition and its treatment.

Other medications besides the benzodiazepines can be used as adjunctive therapies, provided the patient receives benzodiazepines. These include beta-blockers for tachycardia determined to be the result of withdrawal, clonidine for hypertension, and haloperidol for psychosis or agitation, when these signs and symptoms fail to respond to benzodiazepines. Other drugs (such as gabapentin and carbamazepine) that can alleviate symptoms, and may even appear to be preferable (for outpatients or to allow earlier participation in counseling) because of less central nervous system depression, should not be used as monotherapy for withdrawal in patients for whom treatment is indicated to prevent complications. Barbiturates are reasonable alternatives to the benzodiazepines but have a lower margin of safety and no placebo-controlled evidence for efficacy. Further details may be found in Chapter 78.

Infectious Diseases

Alcohol can lead to infectious consequences by various mechanisms. People with alcohol use disorder can have impaired defenses because of undernutrition, splenic dysfunction, leukopenia, and impaired granulocyte function as well as suppression of the gag reflex during intoxication and overdose. Because of these risks, fever in people with alcohol use disorders must not be attributed to a minor viral syndrome or withdrawal unless other causes have been reasonably excluded. For example, though fever and confusion might be attributable to a postictal state or DTs, cerebrospinal fluid examination is warranted to exclude the possibility of meningitis. Though the treatment is the same as for non-addicted persons, pneumonia is more common in people with alcohol use disorders, alcoholism increases the risk of mortality, and hospital treatment is more costly because it takes longer. Concomitant smoking increases the risk by impairing the mucociliary elevator. Causes include aspiration (commonly of anaerobic organisms), Streptococcus pneumoniae, atypical organisms, viruses, Haemophilus influenzae, and Klebsiella pneumoniae.

Tuberculosis is a consideration, particularly when the symptoms are more chronic, weight loss is present, and upper lobe infiltrates appear on the chest x-ray in people with alcohol use disorders who are homeless, have immigrated from a country where the disease is endemic, are known to have a previous positive tuberculin skin test, or have had contact with an active case. Because HIV is more common in people with alcohol use disorders than in the general population, Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia and other opportunistic infections must be considered when pneumonia is diagnosed. Treatment for all of these conditions involves hospitalization in severe cases and antimicrobial therapy directed at the known or likely etiologies, along with observation and treatment for withdrawal symptoms. Other infectious diseases seen in people with alcohol use disorders include sexually transmitted diseases, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, brain abscess, and meningitis. Meningitis in people with alcohol use disorders has a broader differential diagnosis than in the general population. It can be due to S. pneumoniae, Listeria monocytogenes, Gram-negative bacilli, and, in younger persons, Neisseria meningitidis. Brain abscess can result from poor dentition, leading to transient bacteremia and local infection, for example, in a preexisting subdural hematoma. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis occurs in patients with cirrhosis and ascites. Symptoms can include only fever or abdominal discomfort or encephalopathy, with any one of these symptoms absent. Abdominal tenderness may be minimal or absent. Diagnosis is made by paracentesis, which should be done when there is any clinical suspicion. Spontaneous bacterial empyema can occur when pleural effusion is present. Sexually transmitted diseases, including HIV, are more common in people who drink heavily, in part because of sexual risk-taking behavior. Treatment for all of these conditions is guided by local epidemiology, frequently updated resources (e.g., The Medical Letter or handbooks of antimicrobial therapy), and national treatment guidelines for targeted and empiric antimicrobial therapy. Further details may be found in Chapter 79.

Sleep

Though alcohol can help people fall asleep, it also can be stimulating and lead to disrupted sleep and daytime fatigue. In people with alcohol use disorders, a drink may be required to sleep, but sleep is quite disrupted. This situation also is true of the person with an alcohol use disorder in recovery, who may relapse because of intolerable insomnia. Alcohol increases the risk of obstructive sleep apnea and worsens the disease because of its depressant effects on respiration and relaxation of the upper airway. Alcohol can increase the risk of periodic limb movements of sleep. Treatment of insomnia in the person with an alcohol use disorder involves attention to sleep hygiene as well as pharmacotherapy with medications with a low or no risk of dependence, such as trazodone. Further details may be found in Chapter 80.

Trauma

Injury is a common consequence of both alcohol and drug intoxication but may be more likely in people with heavy drinking (40). Trauma, including physical and sexual abuse, can lead to poorer addiction treatment outcomes. Alcohol can interfere with balance and coordination, thus predisposing to injury. It also interferes with judgment, and some heavy drinkers already have a predisposition to risk taking. Heavy episodic (sometimes called binge) drinking (i.e., exceeding 4 standard drinks on an occasion for men, three for women) poses a particular risk of injury and accidents. Patients who present to emergency departments and trauma centers with serious injuries are far more likely than others to have used alcohol recently. Although the evidence from randomized trials is limited and mixed at best, the high frequency of injury in persons with heavy alcohol use suggests that facilities where such persons are seen for health care (i.e., emergency departments and trauma centers) should routinely identify patients with heavy drinking and refer patients with alcohol-related disorders for treatment in order to prevent additional injury. Moreover, addiction specialists should be attuned to the high rates of injury (both past trauma and the risk of future injury) when counseling people with alcohol use disorders. Injury can be a motivating factor for discontinuing alcohol use or a focus of counseling to prevent future injuries. Further details may be found in Chapter 81.

Endocrinologic Consequences

Alcohol causes sexual dysfunction and hypogonadism in men, both through direct effects on the testes and through secondary effects in chronic liver disease, in which gynecomastia may be seen. Alcohol delays menopause and is associated with menstrual disorders such as dysmenorrhea and metrorrhagia. Amounts as little as 1 drink per week have been associated with decreased fertility in women (41). Alcohol increases the high-density lipoprotein fraction of cholesterol, which, in part, may explain observed decreases in coronary artery disease in low-risk drinkers; however, it also increases serum triglycerides, which can lead to heart disease, hepatic steatosis, and pancreatitis. Low-risk drinking can decrease the incidence of diabetes mellitus, but more than 3 drinks a day increase the risk (42). Further details may be found in Chapter 82.

Fetal, Neonatal, and Infant Consequences

Use of alcohol during pregnancy, even in amounts considered to be low risk in nonpregnant adults, can lead to mental retardation and neurobehavioral deficits in children. The fetal alcohol syndrome involves craniofacial abnormalities, neurologic abnormalities, and growth retardation. Affected individuals may have some or all of the manifestations of the syndrome. The neurologic disabilities persist into adulthood. Because no safe amount of alcohol during pregnancy has been identified and there is no treatment for the effects of alcohol on the fetus, abstinence is recommended during pregnancy. Further details may be found in Chapter 83.

Hematologic Consequences

In addition to the iron deficiency anemia that can result from gastrointestinal hemorrhage or chronic blood loss (from variceal bleeding, gastritis, Mallory-Weiss tears, coexisting ulcers, esophagitis, or gastrointestinal cancers), people with alcohol use disorders can develop a pancytopenia (leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, and anemia) from alcohol’s direct toxic effects on the bone marrow. The leukopenia can increase the risk of infections. Splenic sequestration as a result of the splenomegaly associated with cirrhosis and portal hypertension can cause a pancytopenia. People with alcohol use disorders often have not only leukopenia but an impaired quantitative and qualitative white blood cell response to infection. The thrombocytopenia can lead to serious bleeding (e.g., as a result of trauma or varices), when the platelet count is below 50,000. The anemia can be severe. People with alcohol use disorders can be folate deficient, with a megaloblastic anemia. Thus, the MCV, often used to assist in the differential diagnosis of anemia, can be misleadingly normal, with iron deficiency lowering the MCV and hemolytic anemias related to liver disease with reticulocytosis or megaloblastic processes simultaneously increasing it. In these cases, the red cell distribution width should be elevated. The treatment for bone marrow suppression is abstinence; for iron deficiency, it is identification of the cause and iron replacement, and for folate deficiency, it is folate (after testing for concomitant vitamin B12 deficiency and giving treatment, as needed). A reticulocytosis should be seen within 1 to 2 weeks of instituting appropriate treatment. A significant thrombocytosis often develops within days of abstinence. Coagulopathy (manifested as easy bleeding and ecchymoses), confirmed by elevation of the INR and prolongation of the partial thromboplastin time, usually is a result of chronic liver disease, though a trial of vitamin K replacement is warranted at least once. Anemias can be the result of abnormal red blood cell membranes in patients with cirrhosis (i.e., spur and burr cell anemia).

Oncologic Risks

Alcohol is a known carcinogen and increases risk for a number of cancers. These include malignancies of the lip, oral cavity, pharynx, larynx, esophagus, stomach, breast, liver, intrahepatic bile ducts, prostate, and colon (3). Though most of these cancers are associated with heavy alcohol use, often in association with smoking, the increased risk of the cancers often is detectable in large populations at lower levels (19,21). For example, breast cancer risk increases with consumption of less than 1 to 2 standard drinks per day on average (2).

Musculoskeletal Consequences

Musculoskeletal consequences can occur from the chronic heavy use of alcohol. Intoxication to the point of overdose may result in the individual’s remaining in one position for prolonged periods of time. In addition to compression nerve palsies, rhabdomyolysis (with hyperphosphatemia, hyperkalemia, hypocalcemia, and acute renal failure) can develop and cause a compartment syndrome—a surgical emergency that requires release of the pressure by incision of the skin and fascia along with débridement of necrotic tissue. Diagnosis is made when there is a tense edematous limb, often with evidence of trauma, initially with severe pain and later with anesthesia. Because physical signs and symptoms are variable and unreliable, the diagnosis often is pursued with intracompartmental pressures; near-infrared spectroscopy shows promise for early diagnosis, potentially avoiding delays in treatment. Surgical consultation is required. Hyperuricemia and gout are more common in alcohol use disorders. Gout classically presents as podagra, an edematous, exquisitely painful, erythematous great toe. Treatment is with colchicine, using caution in renal or hepatic insufficiency, or indomethacin, using caution in the presence of gastritis or renal insufficiency. The cyclooxygenase-2– specific nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents can be effective in gout and have the advantage that they are safer in patients who are at risk of gastrointestinal bleeding, though they have deleterious renal effects. A brief course of corticosteroids or a single injection of adrenocorticotropic hormone may be safer choices for the person with an alcohol use disorder. Chronic treatment in the setting of renal disease, tophaceous gout, or polyarticular gout should be with allopurinol or probenecid. Saturnine gout is diagnosed when the hyperuricemia is associated with past “moonshine” use. Hyperuricemia can lead to renal insufficiency. Excessive alcohol use (more than 1 drink a day for women, two for men, and heavy episodic drinking) increases the risk of skeletal fracture. What component of this increased risk is due to a higher risk of trauma and what is attributable to alcohol-related osteopenia is unclear. Though low-risk alcohol use can be associated with an increase in BMD (either because of alcohol’s effect on estrogens or other hormones or because of a lifestyle factor associated with increased BMD), excessive consumption leads to osteopenia. Heavy alcohol use can lead to osteonecrosis of bone, such as that at the femoral head.

Vitamin Deficiencies

People with alcohol use disorders are prone to vitamin deficiency because of malabsorption and poor dietary intake. Alcohol has been associated with deficiencies of fat-soluble vitamins when there is malabsorption because of pancreatic disease and also with deficiencies of thiamine, pyridoxine, niacin, riboflavin, vitamin D, and zinc. Symptoms commonly seen in people with alcohol use disorders may not be due to intoxication or withdrawal. For example, thiamine deficiency can cause confusion and ataxia, whereas diarrhea, abdominal discomfort, amnesia, anxiety, insomnia, nausea, seizure, and ataxia may be the result of pellagra. A clue to this diagnosis is the coexistence of glossitis and rash in sun-exposed areas, but these more specific features may be absent. It may even present as alcohol withdrawal (43). Vitamin replacement is safe and should be done empirically.

Consequences in the Perioperative Patient

Heavy alcohol consumption is a risk factor for postoperative complications. In the perioperative period, attention must be given to identifying a risk of withdrawal, managing the withdrawal, and managing the pain. Elective surgery can be an opportune time to try to achieve abstinence, both as treatment for alcohol use disorder and to prevent perioperative morbidity. This approach can reduce morbidity, as has been demonstrated in at least one randomized trial (44). Further details may be found in Chapter 84.

Tobacco

Tobacco use increases the risk of death. In addition, it causes cosmetic effects such as stained teeth, stained fingers, wrinkles, and many medical illnesses.

Cardiovascular Consequences

Smoking can lead to poorer control of hypertension (45) and causes atherosclerosis. Smokers thus are at higher risk of myocardial infarction and sudden death. Moreover, smoking appears to potentiate the risks of heart attack conferred by hyperlipidemia and diabetes. Smoking can precipitate angina by causing vasospasm and hypercoagulability, and it can precipitate dysrhythmia. Smokers are at higher risk of cerebrovascular disease and stroke and peripheral vascular disease, which leads to intermittent claudication, pain, and loss of limb. Smoking lowers the beneficial serum high-density lipoprotein subfraction of cholesterol. The risk of heart disease (46) and peripheral vascular disease and stroke morbidity and mortality decrease soon after smoking cessation. Further details may be found in Chapter 73.

Renal Consequences

The renal consequences of tobacco use disorder are limited primarily to the effects of atherosclerosis of the renal arteries, which can lead to ischemic renal failure and hypertension from renal artery stenosis. Further details may be found in Chapter 75.

Gastrointestinal Consequences

Smoking is a cause of gastric and duodenal ulcers. Smoking can cause and exacerbate gastroesophageal reflux disease. Smoking interferes with ulcer healing. These diseases can require pharmacotherapy in addition to smoking cessation, as with histamine type 2 receptor antagonists, proton pump inhibitors, or antibiotics for Helicobacter pylori. Further details may be found in Chapter 76.

Respiratory Consequences

Smoking leads to chronic bronchitis and emphysema, collectively referred to as “chronic obstructive pulmonary disease” (COPD). Smoking is the leading cause of both COPD and bronchogenic carcinoma. The risks of both of these mortal diagnoses can be lowered with smoking cessation. Smoking cessation can slow the steady decline in pulmonary function seen in COPD (47). Smoking leads to pulmonary hypertension, interstitial lung disease, and pneumothorax. Though some lung cancers can be treated surgically if detected early, chemotherapeutic approaches have been disappointing. Treatment for COPD is somewhat disappointing, particularly when the patient continues to smoke. Effective treatments include bronchodilators, oxygen for hypoxemia, and, less commonly, corticosteroids. Further details may be found in Chapter 77.

Neurologic Consequences

Tobacco use is associated with atherosclerosis, peripheral vascular disease, and, therefore, cerebrovascular disease and ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke. Atherosclerotic disease can involve small vessels and result in cognitive deficits.

Though nicotine withdrawal is not life threatening, the craving can complicate treatment for other medical illnesses. Nicotine replacement should be provided for medically ill patients who are hospitalized. Bupropion and varenicline are alternatives. Nicotine replacement can precipitate myocardial ischemia, but the alternative, smoking a cigarette, also can do so. Therefore, in general, even smokers with coronary artery disease can use nicotine replacement, unless they are experiencing unstable angina or myocardial infarction. Varenicline may also increase cardiovascular risks, but again, smoking cigarettes appears to confer a greater risk. Further details may be found in Chapter 78.

Infectious Consequences

Because of its pulmonary effects, smoking increases the risk of acute and chronic bronchitis and pneumonia. Smokers have more frequent upper respiratory infections. These risks decrease with cessation. Further details may be found in Chapter 79.

Sleep

Nicotine increases the time it takes to fall asleep (sleep latency). Abstinence in tobacco-dependent individuals (i.e., withdrawal) increases daytime sleepiness. Further details may be found in Chapter 80.

Injury

Though smoking does not increase the level of risk associated with risk-taking behavior, tobacco dependence can lead to house fires, smoke inhalation, and death, as well as other accidental death. Anecdotally, smoking in medically ill patients using oxygen has resulted in facial and airway burns and fires. Further details may be found in Chapter 81.

Endocrinologic Consequences

Tobacco use is known to increase the risk of Graves disease (hyperthyroidism) and hypothyroidism. Smoking and nicotine itself can increase insulin resistance (including detrimental effects on lipids and glucose) and risk of diabetes. Estrogen is decreased in male and female smokers, as is sperm number and function in men. Smoking is one of the leading causes of erectile dysfunction, mainly because of atherosclerosis. Cigarette use is associated with decreased BMD, osteoporosis, and fractures. Further details may be found in Chapter 82.

Fetal, Neonatal, and Infant Consequences

Tobacco use during pregnancy causes low birth weight, spontaneous abortion, and perinatal mortality, among other consequences. The risks of sudden infant death syndrome and neurodevelopmental impairment are increased, though studies have had difficulty separating the effects of tobacco, alcohol, nutrition, and social situations. Further details may be found in Chapter 83.

Hematologic Consequences

Though data are conflicting, smoking is known to have hypercoagulable effects, and it can be a risk factor for deep vein thrombosis.

Oncologic Risks

Smoking has been associated with the following cancers: oral cavity, larynx, lung, esophagus, bladder, kidney, pancreas, stomach, and cervix. In addition, smokers with one smoking-related cancer are at higher risk for a second one. These risks decrease with cessation.

Consequences in the Perioperative Patient

Smoking increases the risk of postoperative pulmonary complications, including pneumonia, atelectasis, reactive airways exacerbations, and respiratory failure. Smoking cessation before elective surgery is advisable, though it should be done at least 2 months before surgery (48). Current smokers should pay particular attention to pulmonary toilet perioperatively. Incentive spirometry should be used, along with use of bronchodilators. Further details may be found in Chapter 84.

Opioids, Cocaine, and Other Drugs

The complications of other drugs often are related to route of administration. Injection and inhalation of drugs have particular consequences. In addition to route of administration, drugs have unique organ systems complications.

Injection Drug Use