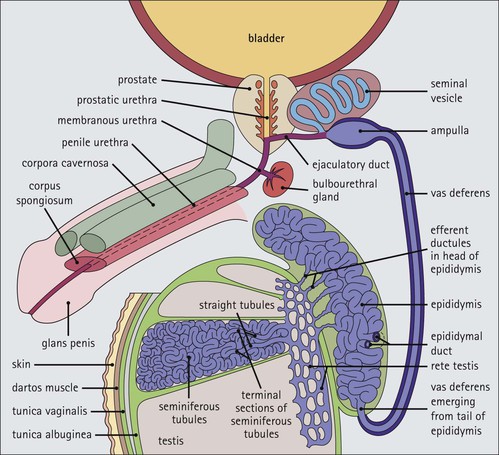

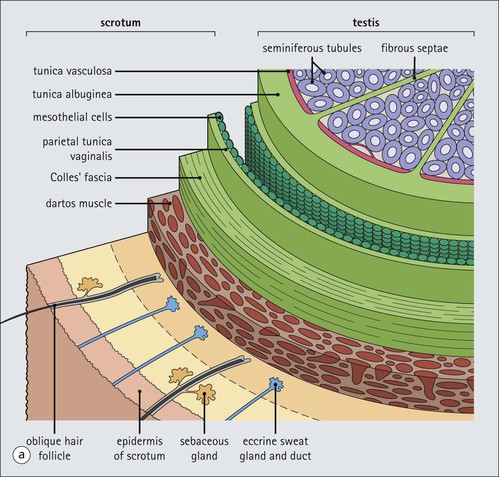

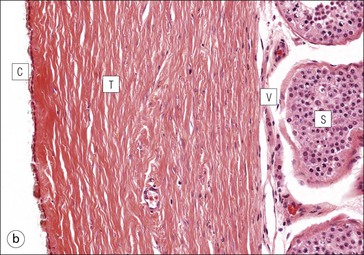

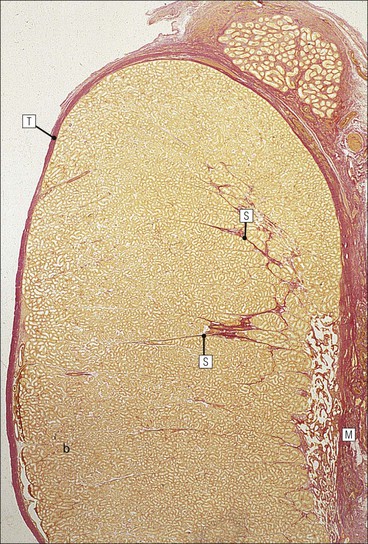

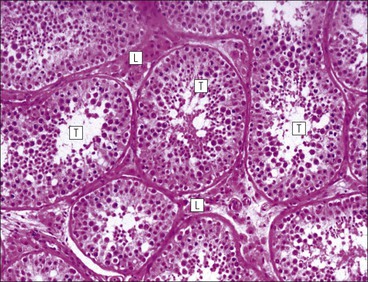

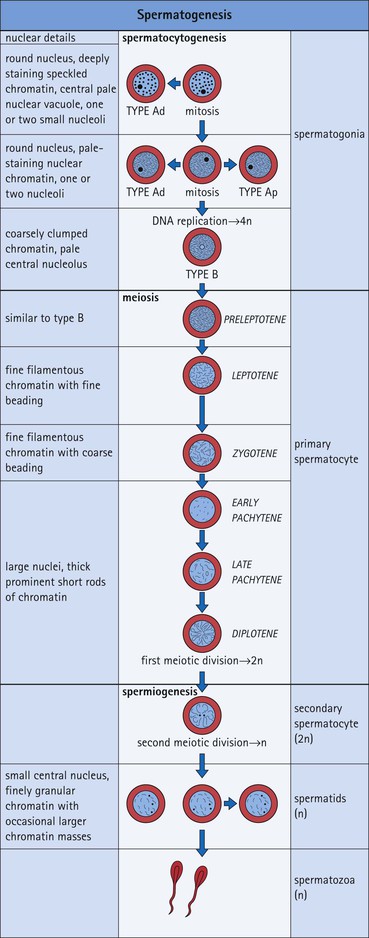

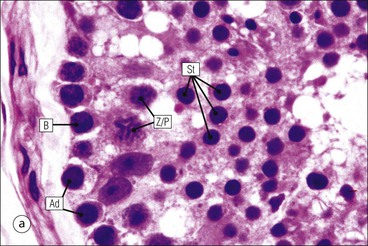

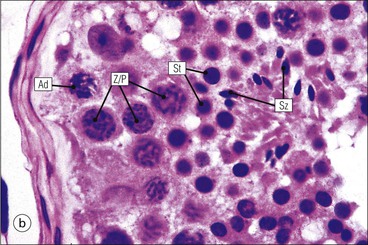

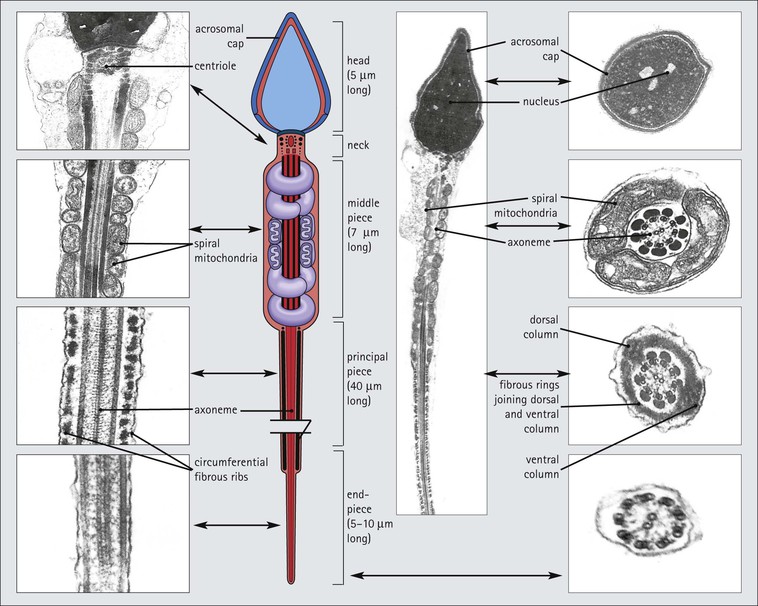

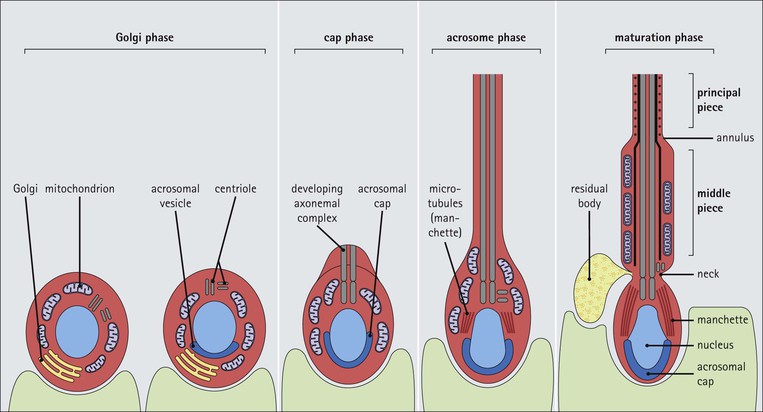

The male reproductive system is responsible for: • Production, nourishment and temporary storage of the haploid male gametes (spermatozoa) • Intromission of a suspension of spermatozoa (semen) into the female genital system Whereas the first two functions are important only during the years of sexual maturity, hormone production is required throughout life, even in-utero. The male genital system (Fig. 16.1) comprises: The testes, epididymis and vas deferens are located in the scrotal sac (Fig. 16.2), which is a skin-covered pouch enclosing a mesothelium-lined cavity continuous with the peritoneal cavity at the inguinal canal. The testes are paired organs located outside the body cavity in the scrotum The location of the testes in the scrotum means that they are maintained at a temperature approximately 2–3°C below body temperature; this is essential for normal spermatogenesis. Embryologically, the testes develop high on the posterior abdominal wall and migrate to the scrotum, usually arriving there in the 7th month of intrauterine life. Sometimes a testis fails to migrate from the posterior abdominal wall and does not arrive in the scrotum. It may stay on the posterior abdominal wall at its site of original development, or it may become stuck on its way down to the scrotum, the common site being within the inguinal canal. This is called ‘undescended testis’ or ‘mal descent of the testis’. Because the testis does not arrive in the cooler environment of the scrotal sac, the germ cells in the seminiferous tubules degenerate and die, without ever producing spermatozoa. This is called cryptorchidism, and the testis remains small and non-functional throughout life, although the testosterone-producing Leydig cells (see p. 325) remain undamaged and functional. Undescended testes have a high risk of developing malignant tumours. Each mature adult testis is a solid ovoid organ approximately 4–5 cm long, 3 cm deep and 2.5 cm wide, and usually weighs 11–17 g. The right testis is commonly slightly larger and heavier than the left. Each testis has an epididymis (see p. 328) attached to its posterior surface and is suspended in the scrotal sac by the spermatic cord containing the vas deferens (see p. 328), the arterial supply and the venous and lymphatic drainage. The testis is completely enclosed by the tunica albuginea, which is thickened posteriorly to form the mediastinum of the testis, projecting some way into the body of the testis (Fig. 16.3). Blood and lymphatic vessels, and the channels carrying spermatozoa, pass through this area (rete testis, see p. 326). Fibrous septa from the mediastinum divide the body of the testis into 250–350 lobules, each lobule containing one to four seminiferous tubules. A seminiferous tubule is a coiled, non-branching closed loop, both ends of which open into the rete testis The rete testis is a system of channels located at the posterior hilum of the testis, close to the mediastinum. Each seminiferous tubule is approximately 150 µm in diameter and 80 cm long. It has been calculated that the combined total length of all the seminiferous tubules in each testis is 300–900 m. In a sexually mature adult, each seminiferous tubule has a central lumen lined by an actively replicating epithelium, the seminiferous or germinal epithelium, mixed with a population of supporting (sustentacular) cells, the Sertoli cells. The lining cells sit on a well-defined basement membrane lying inside a collagenous layer containing fibroblasts and other spindle-shaped cells. These are contractile myoid cells containing intermediate filaments and desmin, like smooth muscle cells. In some animals, these myoid cells form a continuous peritubular layer and contract rhythmically, possibly propelling the non-motile spermatozoa towards the rete testis (spermatozoa only acquire their motility after they have passed through the epididymis). In human testis, the myoid cells form a less distinct layer and are not usually circumferential. The outer wall of the tubule, comprising basal lamina, collagen layer and myoid cell layer, is sometimes called the ‘tunica propria’. Blood vessels and clusters of hormone-producing interstitial (Leydig) cells are found between adjacent seminiferous tubules (Fig. 16.4). Germinal epithelium and spermatogenesis The germinal epithelium lining the seminiferous tubules produces the haploid male gametes (spermatozoa) by a series of steps called, in sequence, ‘spermatocytogenesis, meiosis and spermiogenesis’ (Fig. 16.5). In spermatocytogenesis, the stem cells (spermatogonia) undergo mitosis This mitotic division (see Fig. 2.26) produces not only more spermatogonia but also cells that differentiate into primary spermatocytes (Fig. 16.6). In man, spermatogonia can be divided into three groups according to their nuclear appearances: type A-dark (Ad) cells, type A-pale (Ap) cells, and type B cells. It is thought that type Ad spermatogonia are the stem cells of the system, their mitotic division producing more type Ad cells and some type Ap cells, which further replicate by mitosis to form clusters of daughter cells linked to each other by cytoplasmic bridges. These type Ap spermatogonia mature into type B cells, which divide mitotically to produce further type B cells; these cells then mature in a cluster to produce primary spermatocytes. Primary spermatocytes replicate their DNA shortly after their formation (i.e. they are 4n). Primary spermatocyte formation marks the end of spermatocytogenesis. Meiotic division occurs at the spermatocyte stages Primary spermatocytes pass through a long prophase lasting about 22 days, during which changing patterns of nuclear chromatin enable preleptotene, leptotene, zygotene, pachytene and diplotene stages to be identified (see Fig. 16.5). Meiosis is described on page 33. The first meiotic division occurs after the late pachytene/diplotene stages, with the formation of diploid secondary spermatocytes which rapidly (i.e. within a few hours) undergo the second meiotic division to produce haploid spermatids. Spermiogenesis is the process by which haploid spermatids are transformed into spermatozoa Spermiogenesis can be divided into four phases, all of which occur while the spermatids are embedded in small hollows in the free luminal surface of the Sertoli cells (see p. 327). These four phases are: The details of these phases are shown diagrammatically in Figure 16.7. Mature spermatozoon. The mature spermatozoon comprises a head and a tail region, the latter being composed of a neck, a middle piece, a principal piece and an end-piece (Fig. 16.8). The head of a mature spermatozoon is composed of the nucleus covered by the acrosomal cap The spermatozoon head is flattened and pointed, and the chromatin of the nucleus is condensed and broken only by occasional clear nuclear vacuoles. The acrosomal cap covers the anterior two-thirds to three-quarters of the nucleus; it is a glycoprotein containing numerous enzymes, including a protease, acid phosphatase, neuraminidase and hyaluronidase, and can be regarded as a specialized giant lysosome. The acrosomal enzymes are released when the spermatozoon contacts the ovum; they facilitate penetration of the corona radiata and zona pellucida of the ovum (see Chapter 17

Male Reproductive System

Introduction

Testes

Anatomy and Development

Seminiferous Tubules

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Male Reproductive System

Chapter 16

FIGURE 16.7 Spermiogenesis. In the Golgi phase, PAS-positive granules (pre-acrosomal granules) appear in the Golgi apparatus and fuse to form a membrane-bound acrosomal vesicle close to the nuclear membrane. This vesicle enlarges and its location marks what will be the anterior pole of the spermatozoon. The two centrioles migrate to the opposite (posterior) pole of the spermatid, the distal centriole becoming aligned at right-angles to the cell membrane. It then begins the formation of the axoneme complex of the sperm tail. In the cap phase, the acrosomal vesicle changes shape to enclose the anterior half of the nucleus and become the acrosomal cap. The nuclear membrane beneath the acrosomal cap thickens and loses its pores and the nuclear chromatin becomes more condensed. In the acrosome phase, the increasingly dense nucleus flattens and elongates; an anterior pole, capped by the acrosomal cap, and a posterior pole closely related to the developing axonemal complex can be identified. With the changed shape of the nucleus, the cytoplasm between the acrosomal cap and the anterior cell membrane migrates to the posterior part of the cell. The entire cell orients itself so that the anterior pole is embedded in the luminal surface of the Sertoli cell, pointing down toward the base of the seminiferous tubule; the cytoplasm-rich posterior pole of the spermatid protrudes into the tubule lumen. At the same time, a sheath of microtubules, called the ‘manchette’, extends from the posterior part of the acrosomal cap toward the developing tail. The centrioles (see Fig. 2.22), have migrated posteriorly from the neck of the developing spermatozoon, which is the connecting piece between the head (containing the nucleus and acrosomal cap) and the developing tail. One centriole continues to synthesize the axonemal complex of the sperm tail, producing a regular tubular complex comprising two central microtubules surrounded by a ring of nine peripheral doublets. In the neck region, nine coarse fibres are produced which extend down into the tail around the microtubules of the axonemal complex. Prominent mitochondria aggregate in and below the neck to surround the nine coarse fibres; this forms the segment known as the ‘middle piece’. The mitochondria finish abruptly at a ring (annulus) demarcating the middle piece from the main parts of the tail (the principal piece and end-piece). The maturation phase is characterized by the pinching-off of surplus cytoplasm, particularly from the neck and middle piece regions, and its phagocytosis by Sertoli cells. The immature spermatozoa then become disconnected from the Sertoli cell surface and lie free in the seminiferous tubule lumen, marking the end of spermiogenesis. The immature male gametes are later modified in the ductular systems leading to the penis. The duration of spermatocytogenesis from spermatogonium type Ad to released immature spermatozoon is about 70 days.