Lymphoid and Hematopoietic Tumors

NON-HODGKIN LYMPHOMA

The diagnosis of primary mammary lymphoma is limited to patients without evidence of systemic lymphoma or leukemia at the time that the breast lesion is detected (1). Clinically, the disease should involve only the breast or the breast and ipsilateral lymph nodes. Fewer than 1% of all non-Hodgkin lymphomas and about 2% of extra nodal lymphomas involve the breast (2). The occurrence of synchronous and metachronous lymphoma and breast carcinoma has been described (3). Mammary involvement by lymphoma occurs in some but not all of these patients. In one instance, occult low grade non-Hodgkin lymphoma was found in a mastectomy specimen after the operation was performed for intraductal carcinoma (4).

With rare exceptions, patients described in the literature have been women ranging in ages 13 to 90 at diagnosis, averaging about age 55. Bilateral disease is present in about 10% of patients at the time of diagnosis.

The presenting symptom in virtually all cases is a mass located most often in the upper outer quadrant of the breast. However, nonpalpable non-Hodgkin lymphoma, especially when low grade may be detected by mammography in the absence of a mass (4). A history of recent onset and rapid growth is not unusual. The tumor is often solitary, but patients with multiple lesions and diffuse infiltration have been described. Enlarged axillary lymph nodes have been present clinically in 30% to 50% of patients (5,6,7).

Mammographically, the tumor may be well defined and circumscribed or irregular and thus difficult to distinguish from other lesions (8,9,10). As suggested, diffuse infiltration and multiple ill-defined lesions are radiologic clues to the diagnosis of lymphoma. There is no association between specific subtypes of lymphoma and radiologic findings on mammography (11,12). Mammary lymphomas may be hypoechoic when studied by ultrasonography (12).

The tumors have measured 1 to 12 cm, averaging about 3.0 cm. Histologic examination often reveals that the lymphomatous infiltrate extends into the breast parenchyma beyond the grossly evident mass.

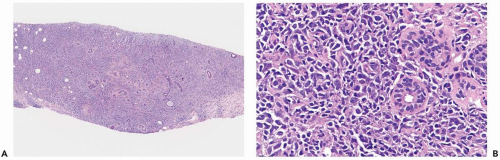

The largest subgroup of primary mammary lymphomas has been described as diffuse histiocytic when classified by the Rappaport system (1,5,6,8) or as diffuse large cell (13) (Fig. 24.1). Poorly differentiated lymphocytic lymphomas, the majority of which are diffuse, and mixed lymphomas, equally nodular and diffuse, are the second and third most common types, respectively (6) (Fig. 24.2). Well-differentiated lymphocytic, lymphoblastic, undifferentiated, Burkitt’s and MALT lymphomas account for 10% to 15% of mammary lymphomas in most series (Fig. 24.3). Diffuse, large cleaved; diffuse, small cleaved; and diffuse or follicular mixed cell lymphomas are the three most common cell types, according to the Working Formulation (6). The majority of mammary lymphomas are of the B-cell type, with infrequent examples of T-cell and histiocytic lymphoma described (10,13,14,15,16,17,18). The recently updated World Health Organization (WHO) classification of lymphomas includes cytogenetic, molecular, and immunophenotypic characteristics of these tumors (19).

Lymphoma in the breast typically consists of a dense population of tumor cells that diffusely infiltrate the mammary parenchyma. Ducts and lobules in the central portion of the lesion are usually obliterated and, in some cases, the stroma develops a dense sclerotic reaction that tends to be associated with blood vessels (Fig. 24.4). Ducts and lobules are better preserved away from the center of the lesion where there is a tendency for the lymphomatous infiltrate to concentrate in and around these structures (Fig. 24.5). A reactive lymphoid infiltrate composed of small lymphocytes is very commonly present at the periphery of the tumor, often localized around epithelial elements and blood vessels. Germinal centers may be formed in these reactive infiltrates (Fig. 24.6). Calcifications are not usually an intrinsic feature of mammary lymphoma, but they may occur coincidentally in epithelial lesions or in fat necrosis.

Extension of lymphoma cells into the glandular epithelium of ducts and lobules may mimic in situ carcinoma or pagetoid spread of carcinoma. Signet ring cell lymphoma bears a striking resemblance to signet ring cell lobular carcinoma, and it may require immunostains for lymphoid and epithelial markers to distinguish between these entities. The appearance of lymphoma involving mammary stroma that is altered by pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia may also be mistaken for invasive carcinoma (13,14). This growth pattern arises when lymphoma cells insinuate themselves into the interstices of pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia (Fig. 24.7). Distinguishing large cell lymphoma from poorly differentiated carcinoma is sometimes difficult, especially when the tumor lacks an in situ carcinoma component (15). Large cell lymphoma may assume solid, diffuse, and sometimes alveolar growth patterns that resemble carcinoma. The limited samples of needle core biopsy specimens provide a setting where there is a risk of mistaking lymphoma for carcinoma. This is one of the many reasons why frozen section examination of needle core biopsy specimens is not recommended.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree