Patient Story

A 60-year-old woman presents with a solid, nontender, movable mass on her upper chest that’s been there for 6 months. It began as a dime-size mass and has been growing more rapidly over the past month (Figure 58-1A). She has lost 10 pounds over the last year without dieting. She has smoked 1 pack of cigarettes per day since age 18 years and gets short of breath easily. Her “smoker’s cough” has gotten worse in the last few months and occasionally she coughs up some blood-tinged sputum. Her family physician excised the mass in the office and sent it to pathology (Figure 58-1B). When the result demonstrated squamous cell carcinoma of the lung, a chest x-ray (CXR) was ordered (Figure 58-2A). The radiologist suggested a CT to confirm the diagnosis (Figure 58-2B). The patient chose to have no treatment and passed away in 10 months of her lung cancer.

Figure 58-1

A. Growing chest nodule in a 60-year-old woman who smoked tobacco her whole adult life. The pathology demonstrated metastatic squamous cell carcinoma from the lung. B. The resected nodule was surgically removed by the family physician in the office. (Courtesy of Leonard Chow, MD, and Ross Lawler, MD.)

Introduction

Epidemiology

- In 2007, lung cancer was diagnosed in 203,546 people in the United States (109,643 men and 93,893 women).1 Both incidence and mortality rates have been decreasing since 1999 for men, but remain level for women.

- Black men have the highest age-adjusted incidence rates (99.8/100,000) followed by white men (75.3/100,000), and then black women (54.7/100,000) and white women (54.6/100,000); Hispanic men (41.5/100,000) and women (26.1/100,000) have the lowest incidence rates.2

- Risk increases with age; at age 60 years, 2.29% of men will develop lung cancer in 10 years and 5.64% in 20 years.1 Among women at age 60 years, 1.74% will develop lung cancer in 10 years and 4.27% in 20 years. Median age at diagnosis is 71 years.2

- In 2007, lung cancer was the leading cause of cancer deaths, accounting for 14% of all cancer diagnoses and 28% of all cancer deaths.3

- The 2011 estimate for new cases of lung cancer in the United States was 221,130 with 156,940 deaths from the disease.4

Etiology and Pathophysiology

- Lung cancer begins in the lungs spreading to regional lymph nodes and regional structures (e.g., trachea, esophagus). Extrathoracic metastases are common (found at autopsy in 50% to 95%) and sites include brain, bone, and liver.5

- Likely caused by a multistep process involving both carcinogens and tumor promoters; a number of genetic mutations (e.g., epidermal growth factor receptor [EGFR] mutations) are present in lung cancer cells, including activation of dominant oncogenes and inactivation of tumor-suppressor oncogenes.5

- There are two main groupings of lung cancer: non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC; most common) and small cell lung cancer (SCLC). The four major cell types responsible for 88% of cases5 are:

- Adenocarcinoma (including bronchoalveolar)—32% of cases.

- Squamous or epidermoid carcinoma—29% of cases.

- Small cell (or oat cell) carcinoma—18% of cases.

- Large cell (or large cell anaplastic)—9% of cases.

- Adenocarcinoma (including bronchoalveolar)—32% of cases.

- Adenocarcinoma, squamous carcinoma, and large cell are classified together under NSCLC because of similar diagnostic, staging, and treatment approaches.4

- Adenocarcinoma and squamous carcinoma have defined premalignant precursor lesions with lung tissue morphology ranging from hyperplasia to dysplasia and carcinoma in situ.3

Risk Factors

- Smoking is the major risk factor; a smoking history (current or former) is present in 90%, with a relative risk ratio of 13 (passive smoke exposure has a risk ratio of 1.5).3 Currently, 28% of men, 25% of women, and 38% of high school seniors smoke in the United States. Women have a higher susceptibility to the carcinogens in tobacco (Chapter 236, Tobacco Addiction).

- Occupations and exposures that increase risk of lung cancer include asbestos mining and processing, welding, pesticide manufacturing (arsenic), metallurgy (chromium), polycyclic hydrocarbons (through coke oven emissions), iron oxide, vinyl chloride, and uranium.3 Home exposure to asbestos or radon and diesel exhaust also increase risk.2,6

- Radiation therapy to the breast or chest.4

- Family history of lung cancer.

- Beta-carotene supplementation in current smokers (small increased risk).

- Hormone therapy (women). In the Women’s Health Initiative, although incidence of lung cancer was not significantly increased, death from lung cancer (primarily NSCLC) was increased (73 vs. 40 deaths; 0.11% vs. 0.06%).7

Diagnosis

Signs and symptoms depend on location, tumor size and type, and the presence of local or distant spread.

- Five percent to 15% of patients are asymptomatic—The cancer is found on chest imaging performed for another reason.5

- Systemic symptoms (e.g., anorexia, cachexia, weight loss [seen in 30% of patients]) may be seen, but the cause is unknown.

The diagnosis of lung cancer requires tissue confirmation through the safest and least-invasive procedure. Procedures include sputum cytology, bronchoscopy, lymph node biopsy, operative specimen, needle aspiration (e.g., endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial approach for mediastinal or hilar lymph nodes or CT-guided transthoracic approach for peripheral tumors), biopsy under CT guidance, or cell block from pleural effusion.5,8

- Immunohistochemistry (e.g., thyroid transcription factor 1 for adenocarcinoma or P63 for squamous carcinoma) is now being used to help differentiate between cell types when morphologic criteria used in resections are not apparent.8 Differentiation is important as different cell types respond differently to treatment.

- For suspicious central lung lesions, sputum cytology (at least three specimens) is a reasonable first step followed by bronchoscopy if needed.5 SOR B

- In patients with a suspicious peripheral lung lesion (especially <2 cm), if sputum cytology fails to confirm the diagnosis, transthoracic needle aspiration has a higher sensitivity than bronchoscopy.5 SOR A

- In patients with a lesion that is moderately suspicious for lung cancer who appear to have limited disease, excisional biopsy and subsequent lobectomy if a lung cancer is confirmed is recommended.5 SOR B

- The most common symptoms at diagnosis are worsening cough or chest pain.4 Symptoms may occur in the following situations:5

- Central or endobronchial growth of the tumor may produce cough, hemoptysis, wheezing, stridor, and dyspnea.

- Collapse of airways from tumor obstruction may cause postobstructive pneumonitis.

- Involvement of the pleura or chest wall may cause pleuritic chest pain, dyspnea on a restrictive basis, or lung abscess from tumor cavitation.

- Regional spread of the tumor may cause tracheal obstruction; dysphagia from esophageal spread; hoarseness from recurrent laryngeal nerve paralysis; dyspnea and elevated hemidiaphragm from phrenic nerve paralysis; and Horner syndrome (enophthalmos, ptosis, miosis, ipsilateral loss of sweating from sympathetic nerve paralysis).

- Spread to lymph nodes may be detected as firm masses in the supraclavicular area, axilla, or groin.

- Extrathoracic metastases are common (found at autopsy in 50% to 95%) and may cause neurologic symptoms with brain metastases; pain and fracture with bone metastases; cytopenias or leukoerythroblastosis from bone marrow involvement; and liver dysfunction from metastases to the liver.

- Paraneoplastic syndromes are common in SCLC and include endocrine syndromes (seen in 12%), such as hypercalcemia and hypophosphatemia from elevated parathyroid hormone or parathyroid-hormone related peptide; hyponatremia from secretion of antidiuretic hormone; electrolyte disturbances as seen with secretion of adrenocorticotropic hormone; and Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome (primarily proximal muscle weakness, abnormal gait, fatigue, autonomic dysfunction, paresthesias). The most common paraneoplastic syndromes in SCLC are the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuresis (15% to 40% of patients with SCLC) and Cushing syndrome (2% to 5% of patients with SCLC).8

- Skeletal and connective tissue syndromes including clubbing (seen in 30%, especially with non–small cell carcinoma) and hypertrophic pulmonary osteoarthropathy with pain and swelling from periostitis (1% to 10%, especially with adenocarcinoma).

- Skin nodules from lung cancer metastases may not be painful but are a poor prognostic sign (Figures 58-1 and 58-2).

- Central or endobronchial growth of the tumor may produce cough, hemoptysis, wheezing, stridor, and dyspnea.

- Molecular testing for mutational profiles is becoming more common for NSCLC with the rapid development of targeted therapies. Specifically, identification of activating EGFR mutations is the best predictor for response to EGFR-tyrosine kinase inhibitors.9 In one multicenter study in Spain, EGFR mutations were found in 16.6% (350 of 2105) of patients and were more frequent in women (69.7%), in never smokers (66.6%), and in those with adenocarcinomas (80.9%).10

- For an incidental lung nodule not believed to be lung cancer, the American College of Radiology (ACR) recommends either percutaneous lung biopsy or whole-body fluorine-18-2-fluoro-2-deoxy-d-glucose-positron emission tomography (FDG-PET), the latter if the patient has lung cancer risk factors.11 Follow-up imaging only is recommended for selected patients with no lung cancer risk factors.

- If a tumor is associated with mediastinal adenopathy, endoscopic/bronchoscopic mediastinal biopsy is recommended.11 In one study, endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration was found to be comparable to mediastinoscopy for mediastinal staging in patients with potentially resectable NSCLC.12

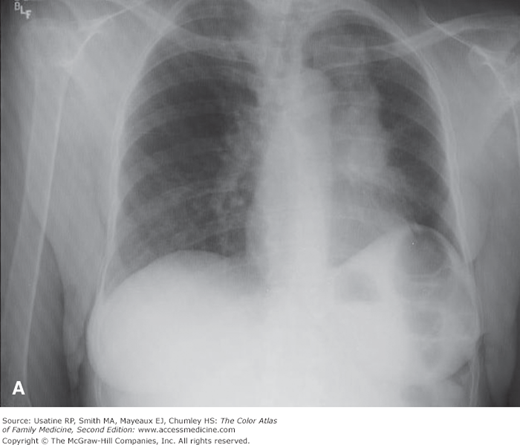

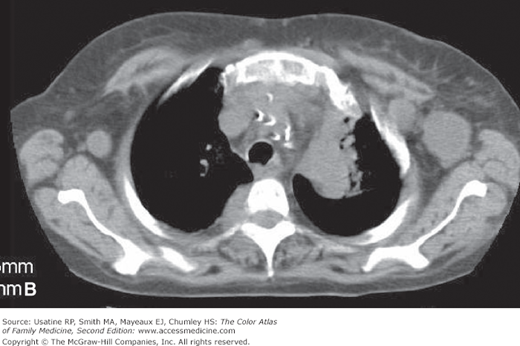

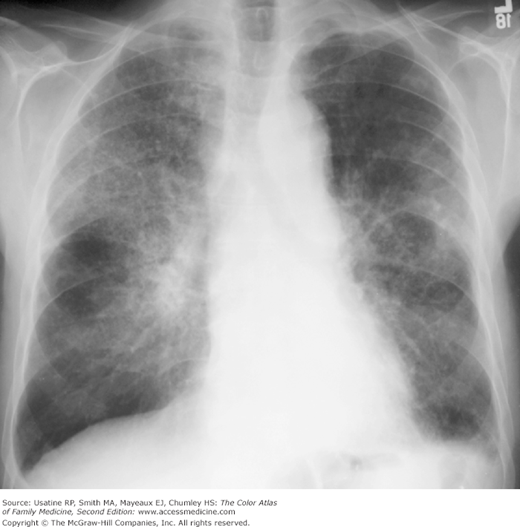

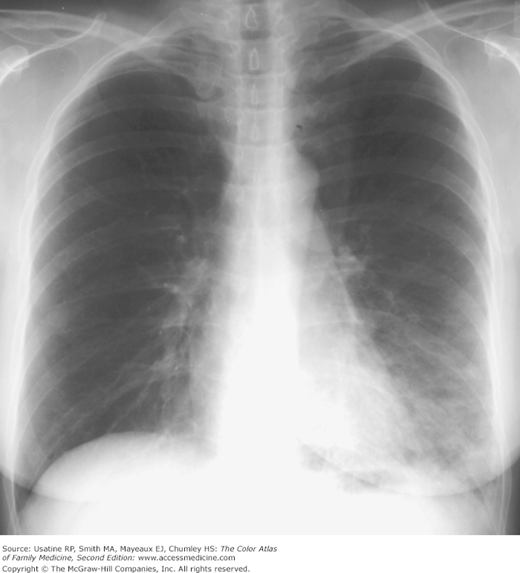

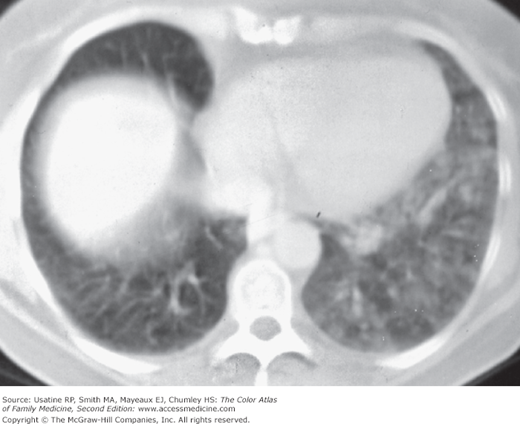

- CXR may be useful as baseline if not already performed and a chest CT scan should be performed; these tests may show a nodule (Figures 58-3 and 58-4) or diffuse lung abnormalities often confused with pneumonia (Figures 58-5, 58-6, 58-7).

Figure 58-4

CT scan of the patient in Figure 58-3 shows a spiculated mass confirmed at surgery to be an adenocarcinoma. (From Diagnostic Thoracic Imaging Courtesy of Miller, W. Diagnostic Thoracic Imaging. New York. McGraw-Hill. 2006.)

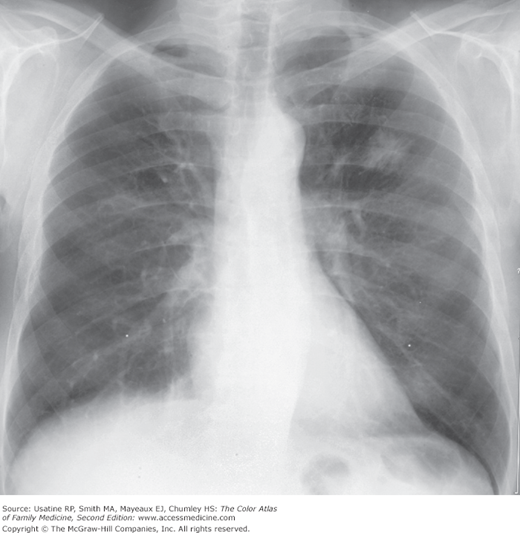

Figure 58-5

Diffuse lung abnormality seen on chest x-ray best characterized as ground-glass opacity, slightly worse in the right upper lobe. Open biopsy demonstrated bronchoalveolar carcinoma. (From Diagnostic Thoracic Imaging Courtesy of Miller, W. Diagnostic Thoracic Imaging. New York. McGraw-Hill. 2006.)

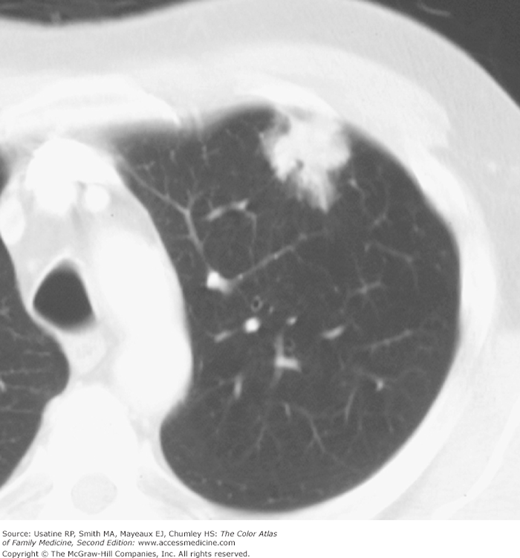

Figure 58-6

Chest x-ray showing local area of consolidation in the left lower lobe. Worsening consolidation for the subsequent 2 months despite antibiotic treatment lead to a surgical biopsy, which confirmed bronchoalveolar carcinoma. (From Diagnostic Thoracic Imaging Courtesy of Miller, W. Diagnostic Thoracic Imaging. New York. McGraw-Hill. 2006.)

Figure 58-7

CT at the level of the bases in the patient in Figure 58-6 showing areas of ground-glass opacification in the left lower lobe and lingula. (From Diagnostic Thoracic Imaging Courtesy of Miller, W. Diagnostic Thoracic Imaging. New York. McGraw-Hill. 2006.)

- Squamous and small cell carcinoma tend to present as central masses with endobronchial growth.

- Adeno- and large cell carcinoma tend to present as peripheral masses, frequently with pleural involvement.