Lobular Carcinoma In Situ and Atypical Lobular Hyperplasia

LOBULAR CARCINOMA IN SITU

Lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS) is a microscopic lesion that does not form a palpable tumor and is rarely detectable by mammography. It is typically discovered coincidentally in breast tissue removed for lesions that produce a mass or when processes that cause mammographic abnormalities lead to a biopsy. Calcifications are infrequently formed in LCIS (1). Mammography has not been an effective method for detecting LCIS and cannot be depended upon to assess the multicentricity or bilaterality of the disease (2,3).

In retrospective reviews, each involving several thousand breast specimens, the frequency of LCIS was 0.5% to 1.5% (4,5,6). Analysis of population based on data from 1978 to 1998 in the United States revealed an increase in the incidence rate of LCIS from 0.90/100,000 person-years to 3.19/100,000 person-years (7). Incidence rates increased continuously throughout the study period among postmenopausal women, with the highest incidence rate among women ages 50 to 59 in 1996 to 1998 (11.47/100,000 person-years). The absence of consistent pathology review creates uncertainty about the reliability of the data, but if it is correct, the increasing use of mammography leading to more frequent biopsies would probably be the most important factor responsible for this change. In particular, columnar cell duct hyperplasia, a condition predisposed to develop calcifications so often coexists with LCIS that this association is probably not coincidental. Columnar cell duct hyperplasia is a frequent benign abnormality responsible for mammographically detected calcifications in the absence of a palpable lesion.

Up to 25% of LCIS patients are postmenopausal when the lobular lesion is identified (8). LCIS occurs infrequently as an isolated lesion in women younger than age 35 or older than age 75. In a consecutive series of more than 1,000 patients treated for breast carcinoma, the mean age (53 years) of women with LCIS was not significantly different from the mean age (57 years) of patients who had infiltrating duct carcinoma (9). LCIS is associated with a high frequency of multicentric ipsilateral carcinoma, including occult invasive foci in 4% to 6% of women who undergo mastectomy (10,11). The contralateral breast is found to harbor LCIS in 40% of cases when a random biopsy is performed on the opposite breast in the absence of a clinical abnormality (12).

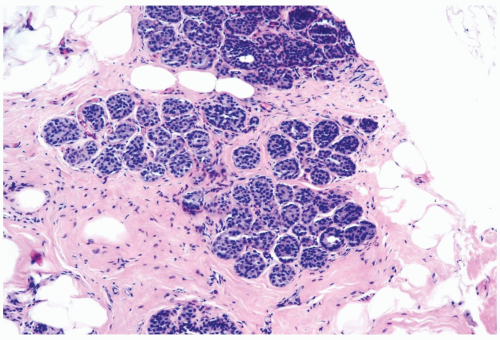

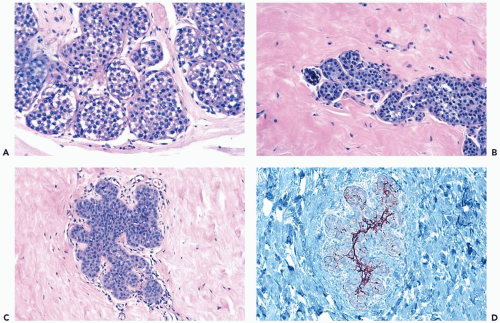

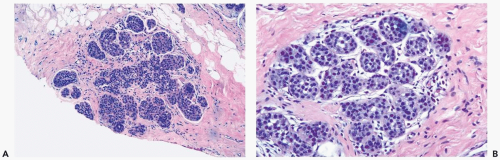

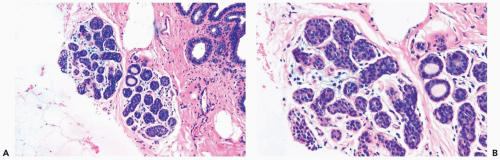

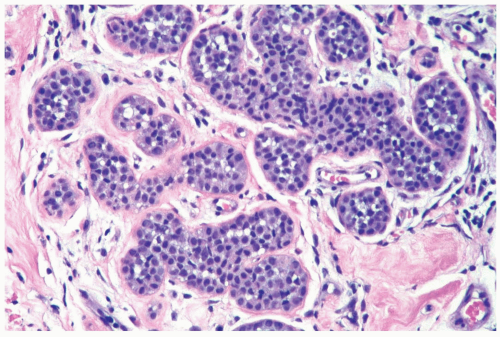

The microscopic distribution of LCIS in lobules and terminal ducts, and alterations in the morphology of these structures, influence the histopathologic appearance of LCIS in any given case. In the typical lobular form, a population of neoplastic cells replaces the normal epithelium of acini and intralobular ductules (Figs. 21.1 and 21.2). The abnormal cells must be sufficiently numerous to cause expansion of these structures. There may be enlargement of the entire lobule in comparison with uninvolved lobules in the adjacent breast, but lobular enlargement is not an absolute diagnostic criterion. The trend to lobular atrophy in postmenopausal women makes expansion of lobular glands an unreliable diagnostic feature in that patient group (Fig. 21.3). If the diagnosis of LCIS is to be meaningful because it identifies a lesion associated with a substantial risk of later carcinoma, then lobular enlargement cannot be regarded as the paramount diagnostic criterion in lesions that have reached an acceptable qualitative level of cytologic abnormality.

The issue of how much lobular involvement is necessary for the diagnosis of LCIS remains unanswered and is of questionable relevance in the diagnosis of needle core biopsy specimens that provide limited samples. Because the number of affected lobules in a biopsy specimen has not proven to be related to the risk for subsequent carcinoma among patients not treated by mastectomy (2,13), there is presently no reason for drawing a distinction between one and two or more involved lobules as a basis for the diagnosis of LCIS (2) (Fig. 21.4). In some instances, the only evidence of a neoplastic lobular proliferation is one lobule in which some, but not all, of the acini are involved. At least 75% of one lobule should be involved to establish a diagnosis of LCIS (Fig. 21.5). Specimens with lesser lesions should be included in the category of atypical lobular hyperplasia.

Loss of cohesion is a characteristic of the neoplastic cells in LCIS, although this is not always readily apparent in acini filled and expanded by the process. When loss of cohesion is prominent and the neoplastic cells have a dissociated distribution, spaces may be created between them that can be mistaken for glandular lumens (Fig. 21.6). Degenerative changes may also disrupt the cellular composition of LCIS. In these situations the neoplastic cells are not arranged in the polarized fashion that characterizes nonneoplastic cells persisting around true glandular lumina.

Loss of cohesion in lobular neoplastic lesions is probably, at least in part, attributable to genetic alterations in the E-cadherin gene that is manifested by absence of membrane E-cadherin immunoreactivity in these cells (14,15). Losses in chromosome 16q 22, the site of the E-cadherin gene, are the most common abnormality found in LCIS (16). Despite the high frequency of somatic E-cadherin mutations in LCIS, germ line E-cadherin mutations are rarely detected in these patients (16,17).

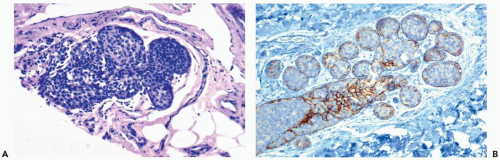

Typically, the neoplastic cells in LCIS have scant cytoplasm and small, round, cytologically bland nuclei that lack nucleoli. This cytologic pattern has been referred to as type A, or classical LCIS (Figs. 21.1, 21.2, and 21.4). When greater cytologic pleomorphism is encountered, the more varied cells have been classified as type B, or pleomorphic LCIS (Fig. 21.7). Pleomorphic LCIS cells have more abundant cytoplasm than cells of the classical type, as well as larger more pleomorphic nuclei that sometimes have nucleoli. The cytologic features of pleomorphic LCIS cells in some instances resemble those of ductal carcinoma. When the lesion is composed entirely of pleomorphic LCIS cells, the distinction between LCIS and intralobular extension of intraductal carcinoma may be difficult to establish. The E-cadherin immunostain is very useful in this situation because absence of reactivity is diagnostic of LCIS (18,19,20,21) (Fig. 21.7). Some examples of LCIS have classical and pleomorphic cell types, both of which are E-cadherin-negative (14).

Figure 21.5 Lobular carcinoma in situ. A, B. A needle core biopsy specimen with minimal diagnostic evidence. Approximately 85% of the lobular glands are involved. |

Intracytoplasmic vacuoles that contain mucinous secretion are usually present in some cells in LCIS, but the presence of mucin can be an inconspicuous feature that must be highlighted with a mucicarmine or alcian blue-PAS (periodic-acid-Schiff) stain (22,23) (Fig. 21.8). An extreme manifestation of this phenomenon is the formation of signet-ring cells having a distended cytoplasmic vacuole that causes the nucleus to be eccentric or indented. Because intracytoplasmic mucin vacuoles are uncommon in the cells of ductal carcinoma and are virtually absent in hyperplastic lesions of duct or lobular epithelium, their presence is an important but not a necessary criterion for the diagnosis of LCIS. Intracytoplasmic mucin is also present in LCIS with clear cell change.

LCIS in atrophic lobules and terminal ducts of postmenopausal women sometimes features cells with dark, eosinophilic-to-basophilic cytoplasm and deeply basophilic, eccentric nuclei (Fig. 21.9). This appearance is probably the result of cytoplasmic condensation associated with loss of cohesion and shrinkage of cells. These cells frequently have intracytoplasmic mucin. In another variant, the cells of LCIS have a mosaic appearance, which results from the presence of distinct cell borders between cells and prominent, round, centrally placed nuclei surrounded by pale cytoplasm (Fig. 21.10). Intracytoplasmic mucin vacuoles can usually be found in this type of LCIS.

Figure 21.6 Lobular carcinoma in situ. Loss of cohesion and focal cellular degeneration have resulted in the formation of spaces in some lobular glands. These are not true acinar lumina. |

Lobular carcinoma in situ typically involves intralobular and extralobular or terminal ductules as well as acinar units within the lobule. In postmenopausal patients with atrophic lobules, duct involvement may be the only manifestation of LCIS (24). The irregular configuration of ductules affected by LCIS has been described as “sawtoothed” or as resembling a cloverleaf. Pagetoid LCIS cells growing beneath the nonneoplastic ductal epithelium may be distributed continuously or discontinuously along the ductal system, undermining and, ultimately, displacing the normal ductal epithelium (Fig. 21.11). The myoepithelial layer is preserved to a variable extent, and it may require p63 and actin immunostains to confirm that it is present. Also, evidence reveals that the cloverleaf pattern sometimes arises de novo in ducts rather than by pagetoid spread (Fig. 21.12). Pagetoid spread of LCIS may also be encountered in papillomas or radial scar lesions. In its most florid form of ductal involvement, LCIS may proliferate to form a solid mass of tumor cells that fill and expand the duct lumen (Fig. 21.13). Foci such as this may develop central necrosis and calcifications that are detectable in mammograms (see Fig. 21.7

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree