28

CHAPTER OUTLINE

Persons with substance use problems are at substantial risk for coexisting medical and mental health problems (see chapters on Medical Disorders and Complications of Addiction and Section Co-Occurring Addictions and Psychiatric Disorders in this text) and often present to medical and mental health settings. Similarly, patients in addictive disorder treatment commonly experience medical and psychiatric problems, which can distract from recovery and increase relapse risk (1–3). In both medical and addictive disorder treatment settings, the provision of comprehensive care for individuals with alcohol and other drug use disorders presents challenges to clinicians who traditionally have been concerned only with issues reflecting their own training and perspectives. For example, medical practitioners typically address the toxic effects of a particular substance, such as seizures or cirrhosis, or the health consequences of a high-risk lifestyle, such as viral hepatitis or HIV. Psychiatrists and other mental health professionals focus on the mental health issues that are prevalent among substance-using patients. Meanwhile, addiction medicine specialists may focus on the individual’s destructive preoccupation with obtaining and consuming a psychoactive chemical substance and the negative consequences of such actions. For the patient, these problems are inseparable, yet the providers operate in distinct systems of care, each with its own—often exclusive—focus. For example, the medical literature contains instances of medical practitioners not attending to the addictive disorders of their patients by failing to screen, intervene, or refer (4–6). Similarly, patients in addictive disorder treatment programs report unmet psychological and medical needs (7,8). It is as if substance-using patients with psychiatric or medical illnesses sometimes are bounced between systems—told that they must be abstinent before they can receive treatment for their psychiatric and medical problems or that they are too sick (medically or psychiatrically) to get into an addiction treatment program—resulting in a clinical “Catch-22.”

Patients who present with complex, interrelated, comorbid problems make apparent the disconnection between these parallel yet typically separate systems of care. The growth of the training of addiction medicine and addiction psychiatry physicians will help to close these gaps. However, for most systems that lack access to certified addiction physicians (9), linkages across the separate medical, mental health, and addictive disorder disciplines will be needed to improve the quality of care delivered to patients with addictive disorders. This chapter briefly reviews the potential benefits to linkages between primary medical care, mental health, and addictive disorder services; identifies the potential barriers to such linkages; and describes published linkage models.

POTENTIAL BENEFITS OF LINKED SERVICES

Effective linkage may benefit individuals with substance use problems in the following common scenarios: when issues related to addictive disorders are not addressed in primary care and mental health settings, when medical and mental health issues are not addressed in addictive disorder treatment, and when the patient is seen in two or more of these settings but no effective communication between or within the systems occurs.

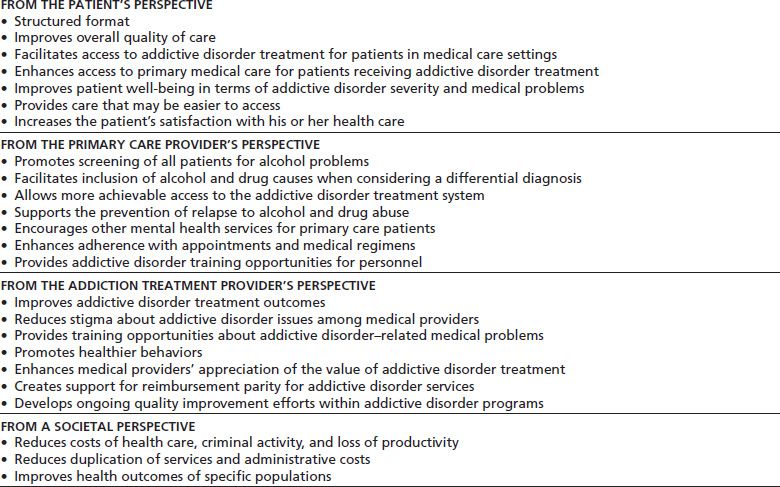

From a patient’s perspective, the potential for improved overall care is the motivating force for linkage of systems (Table 28-1). For example, a patient receiving methadone maintenance who is prescribed efavirenz, which can decrease methadone blood levels, without coordination of care might experience withdrawal symptoms, toxicity, provider unease about possible methadone diversion, or relapse. Other possible benefits from such linkages include the potential for improved pain control in a patient receiving substance abuse treatment services, proper attribution of side effects of medications (vs. substance use or withdrawal), and better access to detoxification and treatment for patients in the medical system. A profound potential benefit of linked systems is the improved well-being of individual patients in terms of addictive disorder severity, medical and psychiatric problems, and overall quality of life (10,11). A pragmatic benefit is the provision of convenient, comprehensive, and coordinated care to patients. As this would likely result in increased service utilization, as noted in the broader spectrum of patients presenting to primary care–based buprenorphine treatment programs (12), careful assessment of its appropriateness would be necessary. Finally, linking services might also decrease stigma, as all providers would acknowledge and support the patient’s recovery efforts, and all medical and psychiatric conditions would be addressed in the same location.

TABLE 28-1 POTENTIAL BENEFITS OF LINKING ADDICTION TREATMENT WITH OTHER MEDICAL AND PSYCHIATRIC SERVICES

From the perspective of the primary care provider and the mental health clinician, possible benefits of linkage include early identification of and relapse prevention for substance use disorders (13), increased consideration of alcohol and drug problems in the formulation of differential diagnoses, better access to addictive disorder treatment services, enhanced patient adherence to appointments and medications, and improved addictive disorder training and experience for personnel. From an addiction treatment provider’s perspective, stronger linkages could yield improved outcomes of addictive disorder treatment, similar to that demonstrated with the addition of needed psychosocial services (14,15). Ready availability of needed medical and mental health services also would allow addictive disorder professionals to do what they do best: focus on the core substance use issues. Exposure to examples of successful treatment could reduce stigma on the part of medical and mental health professionals toward addictive disorders and enhance their appreciation of the value of addictive disorder treatment. Bringing addictive disorder treatment closer to mainstream medical care and exposing its similarities to the care of other chronic illnesses could support the effort to achieve reimbursement parity for addictive disorders. Addictive disorder providers could learn about the medical and mental health complications of addictions and enhance their appreciation of the client’s conditions, health care needs, and prevention approaches. Conceivably, the linkage of services could provide an opportunity to affect other behavior-related issues, such as sexually transmitted diseases (including human immunodeficiency virus) and smoking. Finally, linkage of services could enhance quality improvement efforts within addictive disorder treatment systems—as articulated in an accreditation requirement from the Joint Commission (that accredits health care organizations) (http://www.jointcommission.org/AccreditationPrograms/BehavioralHealthCare/) and by the focus of an Institute of Medicine (IOM) report (16)—by taking lessons from medical settings that have grappled with these issues as part of the restructuring of medical care systems.

From a societal perspective, stronger linkages might lower long-term costs, including savings from reduced HIV incidence and other health-related sequelae of averted substance use, reduced incarceration and other criminal justice expenditures, and increased productivity (17,18). Other benefits include reduced duplication of services across these systems. Finally, a potential public health achievement would be improved health outcomes for specific populations burdened with the substantial morbidity associated with alcohol or drug use disorders.

Medical Training

Many barriers impede better linkage of services. One well-documented problem has been the perspective of many medical practitioners that addressing alcohol and drug abuse issues is not providing medical care and thus is outside his or her purview (19). This viewpoint is slowly changing. Medical education about substance dependence has been sorely deficient in past years (20). In the mid-1980s, medical students’ suboptimal knowledge, perceived responsibility for caring for patients with alcohol use disorders, and confidence in clinical skills were related to reported screening and referral practices; resident physicians perceived even less of a responsibility for care, had less confidence in their skills, and had more negative attitudes (21). These reports suggested that curricula needed improvement and that education, though necessary, may not be sufficient to maintain appropriate attitudes and practices on the part of physicians. Efforts to rectify that situation have been under way, most notably in the past decade, with development of appropriate standards, curricula, and effective addictive disorder educators within many disciplines. Past efforts by the Health Resources and Services Administration and the Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (CSAT) include addiction educators in place in every health professional school in the United States (22–27) and more recently CSAT support for resident physician training in Screening Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment and the creation of the Coalition On Physician Education in Substance Use Disorders (http:// www.cope-assn.org/). Progress requires time, dedicated resources, attention to continuing medical education, and maintenance of high-quality care.

Medical clinicians in practice generally report having received minimal training in substance use disorders, and they screen inadequately for preclinical cases (25,28). Because they neither find patients with less severe addictive disorders nor follow up those who have had success in treatment, most physicians have experienced few successes. This latter product of poor linkages biases the spectrum of medical providers’ clinical experience and further discourages physician involvement. In effect, only patients who do poorly and develop severe medical and psychosocial problems are “ visible” (29). In such an environment, it is difficult to convince even well-meaning providers that the diagnosis and management of these disorders are worthwhile; however, training can help overcome these barriers (30–32).

Payment and Service Linkage Issues

In our current health care system, payment for addiction treatment and mental health care has been limited, compared with payments for other medical services (33,34). Although in recent years, there have been successes in the effort to achieve parity for health care benefits; nonetheless, parity as yet is not the norm.

In 1950, the Uniform Accident and Sickness Policy Provision Law (UPPL) stating insurers are not liable for any loss sustained or contracted while the insured is intoxicated or under the influence of any narcotics was passed. The refusal of reimbursement serves as a disincentive for physicians to screen and document alcohol use, and the opportunity for intervention is missed despite an estimated health savings of 3.81 U.S. dollars for every 1.00 US dollar spent on screening and intervention (35). Since 2001, numerous organizations including the National Association of Insurance Commissioners (the organization that in 1947 adopted the UPPL and encouraged states to implement it as state policy), the American College of Surgeons, and the American Medical Association (AMA) have supported the repeal of the UPPL. In 2010, several states took steps to repeal their UPPLs; for example, in New York, Governor David Paterson (D) signed the No Fault Intoxicated Driver Bill (S.B. 7485) into law, which requires insurance companies to compensate health care providers for emergency services provided regardless of whether the injury was the result of driving while intoxicated. As of 2010, 17 states (WA, OR, CA, NV, CO, SD, IA, IL, IN, OH, ME, CT, RI, MD, DC, NC, SC) had repealed their UPPL.

Moreover, many managed behavioral health plans have “carved out” addictive disorder benefits, separating the financing of care for mental and addictive disorders from that for the rest of the patient’s ailments (36–39a). Such plans have reduced the utilization of services for addictive disorders, and the effect they have had on clinical outcomes, quality of care, integration of care, and physician attitudes remains unclear. Separate systems have frequently fostered the delivery of episodic, poorly coordinated care for substance-using patients.

However, in March 2008, the House of Representatives passed Mental Health and Addiction Equity Act of 2007 (HR 1424), which seeks to improve health for all Americans by granting greater access to mental health and addiction treatment and prohibiting health insurers from placing discriminatory restrictions on treatment. HR 1424 goes beyond the 1996 Mental Health Parity Act, which required equity only for annual and lifetime limits by requiring equity across the terms of the health plan. President Bush signed this bill into law on October 3, 2008, as part of the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008. The Mental Health and Addiction Equity Act became effective in January 2010, and, in February 2010, the Federal Departments of Health and Human Services, Labor, and Treasury issued regulations to implement the federal parity law, and those regulations became effective for most health plans on January 2011. The Mental Health and Addiction Equity Act applies only to group health plans with greater than 50 employees and does not apply to the individual insurance market or group health plans for companies with ≤50 employees, the latter of whom are subject to current state mental health parity requirements. Currently, federal agencies are addressing implementing the Mental Health and Addiction Equity Act while navigating health care reform under the Affordable Care Act, which advocates for equal and quality benefits and mandates inclusion of substance abuse treatment in minimum benefits packages for all Americans (40).

Current systems of payment often do not cover addictive disorder services provided by primary care physicians. Financial reimbursements to medical and behavioral health clinicians generally are taken from separate budgets, and the financial benefits of averted medical complications occur late. Consequently, the cost of treatment for an addictive disorder that prevents subsequent HIV infection may be appreciated as a treatment expense, rather than as a savings of future medical care costs. Another financial disincentive to linked services is the perception that costs of such care may be limitless. The fear of the cost of appropriate addictive disorder services persists, despite analyses that document the limited effect even a worst case scenario would have on health care expenditures (41). In January 2001, the Office of Personnel Management required parity of mental health and substance abuse coverage for all federal employees. A 2006 study comparing seven Federal Employee Health Benefit Plans with a matched set of plans that did not have parity of mental health and substance abuse benefits found that implementation of parity was associated with an increase in service utilization in one of the seven federal plans (+0.78%; p < 0.05), decrease utilization in one of the seven plans (−0.96%; <0.05), and no significant difference in the five other plans (range, −0.38% to +0.23%; p > 0.05 for each comparison). Additionally, they found that there was a statistically significant decrease in spending attributable to parity in three plans (range, −$201.99 to −$68.97; p < 0.05 for each comparison) and no significant change in spending attributable to the implementation of parity in the remaining four plans (range, −$42.13 to +$27.11; p > 0.05 for each comparison). The authors concluded that implementation of parity in insurance benefits for mental health and substance dependence coupled with management of care can improve insurance protection without increasing total costs (42).

In October 2007, the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy announced new health care codes for substance abuse screening and brief intervention. The AMA’s Level I Current Procedural terminology codes (99408 and 99409) went into effect on January 1, 2008, and allow health care providers to report and be reimbursed for structured screening and brief intervention. Now that these codes exist, their success is largely dependent on their uptake and utilization by health care providers. A 2011 study by Harris et al. (43) demonstrated that identifying substance use disorder treatment and diagnosis and procedure codes has a high concordance with chart review, which is a positive indication the codes are being used and are being used appropriately.

Concerns about Confidentiality and Stigma

Well-meaning concerns about patient confidentiality can be barriers to effectively linked medical, mental health, and addiction care. Practical difficulties interfere with obtaining timely two-way written releases of information. Substance dependence programs are required to comply with both the federal confidentiality regulations (42 Code of Federal Regulations [CFR] Part 2) and with the “Standards for Privacy of Individually Identifiable Health Information” final rule (Privacy Rule), pursuant to the Administrative Simplification provisions of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA), 45 CFR Parts 160 and 164, Subparts A and E (http://www.hipaa.samhsa.gov/download2/SAMHSA’sPart2-HIPAAComparisonClearedWordVersion.doc). Addictive disorder information must be specified in information releases to be shared and is often kept separate from the standard medical record. Though the protection of patient confidentiality is noble, in some cases, it can impede integrated care.

The dissemination of electronic health records promises a major revolution in information sharing across systems. Electronic health records create the potential for real-time data-sharing networks, information sharing protocols among the health sector and treatment organizations, central warehousing of health information, and cross-organizational data management. In the United States, projects such as Agency for Health Research and Quality’s State and Regional Demonstration in Health Information Technology Project are working toward interoperability and sharing of patient data between hospitals, physician offices, labs, and other health care providers. However, regulatory barriers, such as patient optin provisions (where patients must give written permission to have their data included in a local or regional registry), will need to be addressed to maximize utility of these systems. Uptake of Internet-based systems in the addiction treatment sector will need an influx of resources, as occurred in the health care sector with the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2008.

Nonetheless, the integration of addictive disorder information into electronic medical records will continue to be challenging. Regulators and clinicians will continue to struggle to balance protections against discrimination with the need for information sharing among health care providers in integrated systems of care. Such integration of care is encouraged by the Affordable Care Act, with central involvement of patient-centered medical homes in treating and managing substance use, with the benefit of electronic medical records and electronic data exchanges (for more information, see http://lac.org/index.php/lac/webinar_archive).

Stigma remains a fundamental barrier in the treatment of any patient with alcohol or drug abuse. In addition to effects on patient behavior, such as limiting recognition of needs and readiness to accept services, stigma might result in medical clinicians’ disinclination toward spending time addressing drug and alcohol issues or a perception of diminished stature of substance abuse treatment providers. Both outgrowths of stigma impede the overall progress.

Medical and mental health providers often inadequately appreciate the efficacy of treatment for addictive disorders despite an overwhelmingly supportive body of research. For example, physicians do not appreciate the comparable therapeutic value of treatment for alcohol or opioid dependence relative to standard treatment for other chronic disorders, such as diabetes mellitus or asthma (44–46).

In summary, the barriers to an integrated system of care for patients with substance use disorders are manifold. Barriers include issues of professional responsibility, education among providers, financial disincentives, concerns about confidentiality, and stigma, among others. Though the barriers can appear to be extensive, they are not insurmountable. At the “macro” level, addressing systems linkages would go a long way toward improving integrated care. Examples of system approaches include implementation of the following: linkage models of care, payment systems that encourage linkage, and quality measures that value coordinated care. Parity of health care benefits for mental health, addictive disorders, and medical problems (as part of legislative efforts in Connecticut and Minnesota) can help to reduce stigma and improve care coordination, but impediments to the care of addictive disorders in primary care settings exist even in states where parity legislation has been enacted. These impediments include the arbitrary health insurance practice of discounting or denying primary care reimbursement for visits in which the provider indicates a mental or addictive disorder as the primary diagnosis (47).

Confidentiality issues can be addressed at the system level by having all care occur under the umbrella of one health system facilitating records availability and at an individual patient–clinician level by having office systems that prompt clinicians and staff to obtain patient information releases to allow health care providers to communicate. Recently published and future studies demonstrating the feasibility and effectiveness of these models should help to convince payers and practitioners of the need to move in this direction.

The growth of office-based opioid agonist treatment has enhanced communication between some primary medical care providers and opioid treatment staff members and provides models for the opportunity of integrated medical and/or psychiatric care with addiction treatment. At the clinician level, various approaches can be taken simultaneously to help overcome the barriers to integration. Physician attitudes, skills, and practices can be changed by active learning educational programs (30,31). Convincing theoretical and empirically proven benefits of linked services also will lead clinicians to favor better-integrated care (48–50).

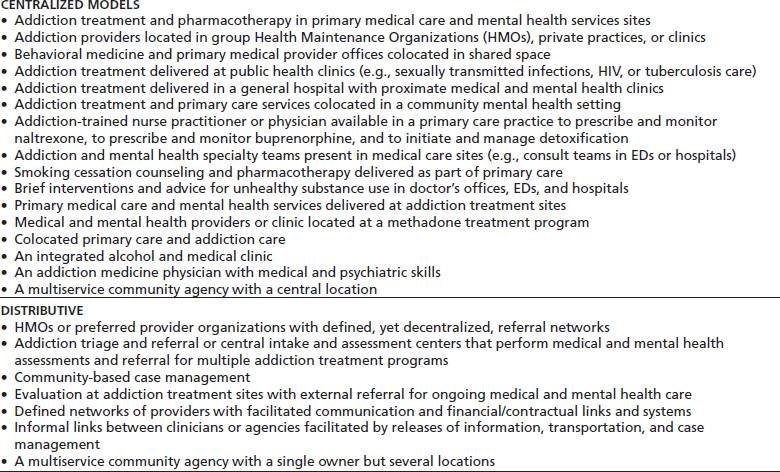

Alcohol and drug-abusing patients use services in “inefficient” ways (e.g., emergency department [ED] presentations rather than outpatient clinic visits), and they do not receive care in the continuous, longitudinal, and comprehensive manner that is often essential for the high-quality management of any chronic disease (51–54). Two basic models have been proposed to bring the system of care for patients with substance use disorders closer to a primary care or chronic disease management (CDM) model (Table 28-2). One model uses a centralized approach in which treatment of addictive disorders, primary medical care, and mental health services are colocated at a single site. A second model uses a distributive approach to facilitate effective patient referrals to services at different sites. This section describes these models of linked primary medical, mental health, and addictive disorder services and reviews the available evidence of their success in facilitating the multidisciplinary care of addicted patients (16).

TABLE 28-2 FEATURES OF CENTRALIZED AND DISTRIBUTIVE INTEGRATED SERVICE MODELS

Centralized Models

Centralized or onsite models bring primary care, mental health, and/or addictive disorder services together at a single site. This fully integrated, “one-stop-shopping” model has been best described in primary care medical clinics and in addictive disorder treatment programs. In addition to overcoming the substantial political, bureaucratic, attitudinal, and financial barriers that separate addicted persons from needed services (55,56), centralized delivery overcomes the problems of geographic separation, patient disorganization, and poor motivation that inhibit patients with addictive disorders from keeping outside appointments (56,57).

Willenbring and Olson (58) reported favorable results for a model of integrated medical and alcohol treatment in a specialty clinic, so-called “backward integration” for poorly motivated, medically ill individuals with alcohol dependence. Their model included at least monthly visits (30), outreach to patients who missed appointments (22), clinic notes that cued the primary care provider to monitor alcohol intake at each visit (59), provider-delivered brief advice that emphasized reducing the harm from alcohol use and cutting down rather than strict abstinence (60), verbal and graphic feedback of improvement and deterioration in biologic markers such as gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT) (61), and onsite mental health services as needed (62,63). In a randomized design, medically ill alcohol-dependent patients in the integrated clinic were compared with similar patients referred to traditional alcohol dependence treatment and ambulatory medical care. During 2 years of follow-up, patients in the integrated clinic had improved alcohol treatment outcomes (including greater abstinence), improved outpatient visit adherence, and lower mortality. Though this model may prove too elaborate for many primary care settings, it serves as a starting point for a disease management system for substance use disorders similar to those used for asthma, diabetes mellitus, and congestive heart failure (51,64). With further study, this model may prove cost-effective for recalcitrant alcohol-dependent patients or for other poorly motivated or complicated substance-abusing patients. Less resource-intensive intervention models developed for problem drinkers in primary care also have proved feasible. The cost analysis of project Trial for Early Alcohol Treatment, a randomized study of physician-delivered brief interventions, showed substantial improvements in drinking outcomes and substantial savings for society and health systems (65

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree