99

CHAPTER OUTLINE

■ FEDERAL REGULATIONS AND MARIJUANA

■ PRESCRIPTION DRUG MONITORING PROGRAMS

■ EMERGING OPIOID RISK DATA AND RELEVANT ISSUES

INTRODUCTION

The Institute of Medicine, of the U.S. National Academy of Science, in a landmark report entitled “Relieving Pain in America,” detailed the epidemic of chronic pain in the United States. Their 2011 report estimated that chronic pain affects nearly 100 million American adults (1). Concomitantly, the use of opioids to treat chronic nonmalignant pain has become commonplace, and the United States now consumes 80% of the global opioid supply (2). There has been a “perfect storm” in the United States regarding the treatment of chronic pain. The recognition of undertreated pain and the excessive use of opioids reflect seemingly contradictory public health problems, and the Centers for Disease Control has reported that prescription drug overdose, predominantly involving opioids, is the leading cause of accidental death in adults aged 25 to 64 (3,4). This challenging reality has led clinicians, regulators, and lawmakers to reevaluate the indications and use of chronic opioid therapy (COT). Accordingly, health care providers must have sound knowledge of the federal and state regulations that govern the use and allocation of controlled substances. The following chapter will highlight some of these regulations and provide a brief overview of the current legal and medical controversies regarding opioids.

FEDERAL OPIOID REGULATIONS

Historically, federal regulations governing controlled substances have been based on two major concepts: transparency or truth in labeling and the appropriate distribution/use of controlled substances. Truth in labeling protects consumers from an educational standpoint, and the appropriate use of controlled substances limits access to these substances, thereby protecting the public at large from drugs of abuse. Federal regulation of controlled substances began in the United States over 100 years ago with the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906. This statute was enacted to ensure that medications had proper labeling and were unadulterated before reaching the consumer (5). Established in 1914, the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act was developed to impede the abuse of addictive drugs and was followed by the Marijuana Tax Act of 1937 (5). Amphetamines, barbiturates, and hallucinogens were brought under regulation in 1965 under the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (5).

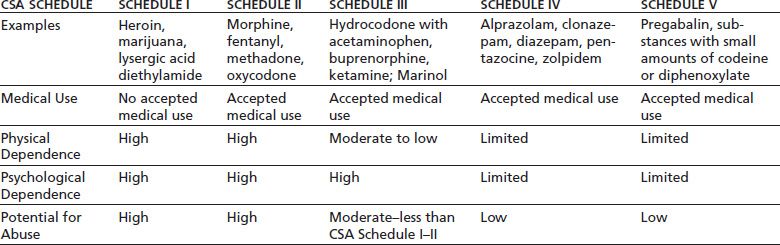

The U.S. Congress sought to consolidate the various federal regulatory statutes governing drugs of potential abuse, and in 1970, the Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act was created. Title II of this policy is the Controlled Substances Act (CSA), which is the primary set of federal regulations that govern the medical use of controlled substances in the United States. Under the CSA, controlled substances are divided into five schedules that are predicated on the following characteristics: potential for abuse, pharmacologic effects, scientific properties, pattern of abuse, public health risk, psychological or physiologic dependence, liability, and whether or not the substance is an immediate precursor of a substance already classified under a CSA schedule (6). As reflected in Table 99-1, Schedule II–IV drugs all have accepted medical use and primarily differ based on varying degrees of physical/psychological dependence and abuse potential. Each drug schedule also carries differing criminal penalties for unlawful use outside of accepted standard medical practice. The implementation and enforcement of the CSA are currently assigned to the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) in the Department of Justice.

TABLE 99-1 THE FIVE CSA SCHEDULES AND COMPARISON OF THE CRITERIA FOR SCHEDULE DETERMINATION

Drug Enforcement Administration. Drug fact sheets. Available at: http://www.justice.gov/dea/druginfo/all_fact_sheets.pdf. Accessed March 2, 2013. Ref. (7).

Federal regulations allow opioids to be prescribed for legitimate medical purposes, including both acute and chronic pain (8). Methadone and buprenorphine are used to treat pain as well as for opioid detoxification/maintenance treatment. Although no special DEA registration is required to prescribe buprenorphine for pain, when used for detoxification/maintenance therapy, methadone and buprenorphine have additional regulations and requirements for prescribers that are not required for prescribing opioids for pain (9–11). Although reviewing the special requirements for using these drugs in detoxification/maintenance therapy is beyond the scope of this chapter and is covered elsewhere in this text, the lack of such requirements for prescribing these drugs for pain should in no way imply that they are safer in such settings or that they need any less vigilance (12). In fact, the statistics may indicate just the opposite. Studies suggest that methadone is the most frequent opioid associated with unintentional overdose death (13). Although methadone accounts for less than 5% of the opioids prescribed for pain, it is associated with one-third of the overdose deaths (14,15). Buprenorphine has been classically believed to have lower abuse potential than other opioids and a much lower potential for respiratory depression. These beliefs are increasingly being challenged by new reports of rising buprenorphine abuse and toxicity, particularly when combined with other CNS-active drugs or respiratory depressants (16).

Products containing tramadol are not currently listed within any of the schedules under the CSA. Presumably, this was due to lack of substantial concern about the abuse potential for these products at the time. Tramadol is an opioid with other potential mechanisms of analgesia, and recently, concerns about abuse potential have led several states to schedule tramadol and tramadol-containing products as a Schedule IV drug under their state law [including Arkansas, Illinois, Kentucky, Mississippi, New Mexico, New York, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Tennessee, West Virginia, and Wyoming].

FEDERAL REGULATIONS AND MARIJUANA

Eighteen states and the District of Columbia have enacted laws that allow for the provisional use of marijuana to treat various medical ailments and, in 2012, two states voted to approve laws that allow for the recreational use of marijuana (17). Proponents of medical marijuana assert that it is an effective treatment for pain, appetite stimulation, glaucoma, nausea, spasticity, and movement disorders, among other ailments (18,19). Despite state laws, the federal government classifies marijuana as a Schedule I substance, signifying that it has no accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse. Under federal law, it is illegal to possess any amount of marijuana, and first-time possession carries a penalty of up to 1 year in prison and a maximum fine of $2000 (20). Thus, in some states, state and federal laws appear to be in conflict over the use of marijuana, and a debate is growing over whether or not state law can supersede federal law.

Opponents of medical marijuana cite the CSA and the Supremacy Clause, Constitutional Article VI, Clause 2, which states, “This Constitution, and the Laws of the United States which shall be made in pursuance thereof; and all treaties made, or which shall be made, under the authority of the United States, shall be the supreme law of the land; and the judges in every state shall be bound thereby, anything in the constitution or laws of any state to the contrary notwithstanding” (21–23).

Proponents of medical marijuana believe that marijuana does have legitimate medical uses with limited abuse potential and should therefore not be a Schedule I substance (24,25). The federal government does not appear to share this perspective, as some “state-legalized” medical marijuana dispensaries have been prosecuted (26).

Physicians are regulated by both state and federal regulations and are expected to comply with all regulations. In states where the use of marijuana may be legal, it is not exactly clear where state law stands on the concurrent use of marijuana and other controlled substances. Prescribing ongoing controlled substances to individuals known to be using/ abusing a Schedule I drug (i.e., a substance with no known or approved medicinal purpose) is typically inappropriate or illegal (27). The Supremacy Clause of Constitutional Article VI, as well as the doctrine known as preemption, suggests that when in conflict, the laws of the higher form of government will prevail (i.e., federal law trumps state law) (28). When regulations are in conflict, clinicians are often advised to adhere to the most conservative or restrictive regulations; however, the exact course of action for adherence to the law may not be so clear, and clinicians must refer to official counsel for legal advice on these issues (28). As more states enact legislation allowing for the use and possession of marijuana, medical or otherwise, it will be helpful if federal or state law clearly defines the prescribing limits for controlled substances as it relates to individuals who use marijuana in compliance with their state laws.

In December 2012, when President Obama was asked if he supports legalized marijuana, he replied, “It does not make sense, from a prioritization point of view, for us to focus on recreational drug users in a state that has already said that under state law, that’s legal” (29). Nonetheless, in the same news report, the U.S. Attorney for Colorado, John Walsh, indicated that regardless of the new state laws that had been passed related to the legalized use of marijuana, the U.S. Department of Justice had the responsibility to enforce the federal CSA. The U.S. Attorney John Walsh was quoted as follows, “Neither states nor the executive branch can nullify a statute passed by Congress.” He goes on to state: “Regardless of any changes in state law, including the change that will go into effect on Dec. 10 in Colorado, growing, selling or possessing any amount of marijuana remains illegal under federal law” (29).

FEDERAL AGENCIES

The Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA)

Health care providers who wish to prescribe controlled substances must be registered and obtain a provider number through the DEA. The DEA is part of the U.S. Department of Justice and does not directly regulate medical practice but does investigate practitioners who do not comply with the laws regarding distribution of controlled substances (30). These investigations can lead to revocation of the provider’s DEA registration and/or criminal prosecution.

According to the DEA, common behaviors that result in investigation include issuing prescriptions for controlled substances without a bona fide physician–patient relationship, issuing prescriptions in exchange for sex, charging fees commensurate with drug dealing rather than providing medical services, issuing prescriptions using fraudulent names, and self-abuse by practitioners (30). The DEA reported in 2006 that, in any given year, less than 0.01% of physicians in the United States lose their controlled substance registrations based on a DEA investigation, and most investigations of physicians that result in loss of DEA registration are initiated by state medical boards (30).

Federal DEA registrations are valid for 3 years, and the DEA Certificate of Registration must be kept at the registered location and be readily retrievable for inspection purposes (31). Currently, requirements to obtain a DEA number are associated with the provider meeting criteria for licensing, but there are no requirements for continuing medical education credits. In 2011, a bill was introduced in Congress that sought to require 16 hours of mandatory continuing medical education (CME) to obtain a DEA number, but the bill failed to pass (32). In light of the current state of excessive opioid prescribing and an epidemic of prescription drug abuse, it seems likely that similar bills may be introduced in the future.

In 2006, the DEA released an updated Practitioner’s Manual that summarizes the federal regulations regarding controlled substances and the CSA. The complete manual can be found at the following Internet link under “publications”: www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov (33). Also in 2006, the DEA released a statement entitled “Dispensing Controlled Substances for the Treatment of Pain” (34). Health care providers are encouraged to familiarize themselves with these two documents as they provide important information regarding the legal use of controlled substances.

In 2007, the DEA limited the amount of Schedule II controlled substances that can be prescribed to no more than a 90-day supply with a new prescription being required if continued use is deemed medically necessary beyond this period (35). Prescribers also must follow their state law that may have limits that are less than the federal 90-day period. Refills on Schedule II drugs are never allowed, but the DEA determined that practitioners may provide patients with multiple prescriptions, to be filled sequentially, for the same Schedule II controlled substance. This allows practitioners, in states where this practice is also legal, to issue multiple, incremental prescriptions to provide up to a 90-day supply of a Schedule II medication. When using such sequential prescriptions, the prescriber indicates that the prescription should not be filled until a later date that is clearly written on the prescription. However, it is required that each prescription also be dated with the date on which the prescription was written. Thus, such multiple prescriptions might each have the same date (indicating the date they were written) but different fill dates for when a pharmacist can fill the prescriptions. However, prescribers must be certain that such multiple prescribing practices are also allowed in their state. In 2010, the DEA determined that practitioners who are registered with the DEA can prescribe scheduled substances electronically through special procedures (36).

The Food and Drug Agency (FDA) and Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS)

The Food and Drug Agency (FDA) has the authority to require pharmaceutical manufactures to develop Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS) under the Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act (FDAAA) of 2007 (37). The REMS requirement is to ensure that the benefits of the substance outweigh its potential risk and to address drug class–specific education (37). Historically, the FDA has used various risk management strategies for other drugs before the REMS requirement was applied to opioids (38).

The FDA released a REMS for transmucosal immediate-release fentanyl in December of 2011. To address the growing problem of opioid overdose and misuse, the FDA requested that certain manufacturers of long-acting opioids (LAOs) develop REMS for their products. In 2011, the FDA, in collaboration with the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy, issued a directive requiring stakeholders to develop comprehensive REMS for LAOs within 120 days of receiving the directive (39). The LAO manufacturers were required to financially support the development and implementation of voluntary CME in regard to their products. The FDA released the final REMS requirements for extended-release/long-acting opioids (LAOs) in July of 2012. These include products such as extended-release morphine, extended-release oxycodone, and extended-release transdermal fentanyl. These REMS have drawn criticism due to the voluntary nature of its CME education. Some have suggested that voluntary CME education is unlikely to make a substantial difference in the epidemic of prescription drug abuse and that ineffective REMS education could be a prelude to a requirement of mandatory education for prescribers. As noted above, such a bill mandating CME education was introduced, but failed to pass, during the 2011 Congressional session (32). The FDA is continually evaluating substances, and the updated list of REMS can be found at the following Internet link: http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/ucm111350.htm. Accessed March 3, 2013. Further, the FDA has made several recent changes, including relabeling extended release opioids and re-scheduling hydrocodone compounds.

The FDA has issued several consumer warnings on the disposal of controlled substances. The transdermal fentanyl patch was recently highlighted by the FDA for its potential for serious risk to children or others who may find and use discarded patches. One can extrapolate similar concerns for any controlled substance product that leaves residual drug to be discarded following proper use. Such products would include the transdermal buprenorphine patches and possibly transmucosal fentanyl products as well as others. These warnings have highlighted the growing necessity for prescribers to educate their patients and the patient’s family or caregivers about the safe use, storage, and disposal of controlled substances. Responsible opioid prescribing necessitates that patient education about these topics be a prominent part of the provider–patient treatment agreement (40). Patient education resources can be found in many locations, and two such websites include the National Institute of Health (NIH)–NIDA Opioid Risk site (www.opi-oidrisk.org) and Opioids911-Safety (www.opioids911.org).

State Medical Boards and Regulations

State medical boards have the responsibility for licensing physicians. The regulations and requirements regarding licensing can vary significantly from state to state. State medical boards are also responsible for determining whether their licensees are practicing within or below the standards of medical practice in their state. Medical boards usually look to experts and particularly to professional groups to help determine the standard of care.

Multiple professional organizations have published guidelines regarding the use and prescribing of controlled substances. Many states have turned to these recommendations for guidance when drafting state legislation and medical policy. Originally adopted in 1998 and later revised in 2004, the Federation of State Medical Boards (FSMB), a national nonprofit organization representing 70 medical and osteopathic boards, released “Model Policy for the Use of Controlled Substances for the Treatment of Pain” (41). This policy was developed to assist medical and osteopathic medical boards when evaluating cases involving the prescribing of opioid analgesics. The FSMB announced in Nov 2013 an update to this policy (http://www.fsmb.org/pdf/pain_policy_july2013.pdf. Accessed November 22, 2013).

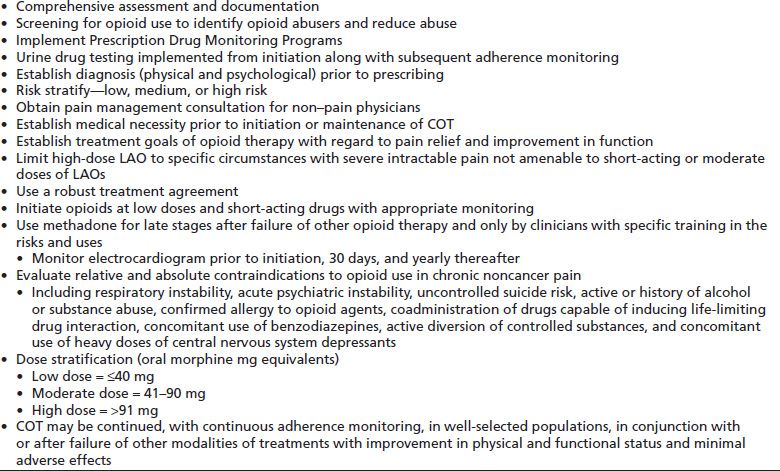

The evidence to guide decisions about the efficacy of opioid use in chronic noncancer pain (CNCP) remains weak to inadequate. The American Pain Society (APS) and the American Academy of Pain Medicine (AAPM) produced “Clinical Guidelines for the Use of Chronic Opioid Therapy (COT) in Chronic Noncancer Pain (CNCP)” in 2009 (42). In 2010, the Cochrane Collaborative released its “Long-term Opioid Management for CNCP,” which represented an interpretation of the best data available (43). The summary statement from the Cochrane review states, “The findings of this systematic review suggest that proper management of a type of strong painkiller (opioids) in well-selected patients with no history of substance addiction or abuse can lead to long-term pain relief for some patients with a very small (though not zero) risk of developing addiction, abuse, or other serious side effects. However, the evidence supporting these conclusions is weak, and longer-term studies are needed to identify the patients who are most likely to benefit from treatment.” In 2012, the American Society of Interventional Pain Physicians released its “Guidelines for Responsible Opioid Prescribing in Chronic Non-Cancer Pain.” Among the many provisions, this evidence-based guideline stressed many expectations associated with responsible opioid prescribing, which are listed in Table 99-2 (44). The most recent set of opioid prescriber recommendations was the result of the National Summit for Opioid Safety, which convened in the Fall of 2012. This summit drafted “Principles for more selective and cautious opioid prescribing,” which are summarized in Table 99-3 (45).

TABLE 99-2 MAJOR PROVISIONS OF THE 2012 AMERICAN SOCIETY OF INTERVENTIONAL PAIN PHYSICIANS GUIDELINES FOR RESPONSIBLE OPIOID PRESCRIBING IN CHRONIC NONCANCER PAIN

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree