Chapter 28 Constipation has many causes, ranging from inadequate fiber to colon cancer. Medications are an important cause (Table 28-1). Systemic disease may cause constipation through neurologic gut dysfunction, myopathies, and electrolyte imbalances. Diabetic patients may have autonomic nerve dysfunction. Structural causes can be the result of a congenital defect or the structural obstruction of a mass, which may be cancerous. Any sudden change in bowel habits warrants a thorough investigation. The primary cause is a disturbance in motility; secondary causes include medications, malignancy, and non-GI disease. TABLE 28-1 Medications and Other Agents That Contribute to Constipation • American College of Gastroenterology guidelines for diagnosis and management of chronic constipation and irritable bowel syndrome: Chronic Constipation Task Force, Am J Gastroenterol 100(Suppl 1):S1-S22, 2005. • Psyllium is likely to be beneficial. • Polyethylene glycols are effective. • Lactulose is likely to be beneficial. • First-line treatment with unproven benefit: lifestyle changes, paraffin, seed oils, magnesium salts, phosphate enemas, sodium citrate enemas, bisacodyl, docusate, glycerol/glycerin suppositories, and senna • Nonpharmacologic treatment fluids and fiber (Table 28-2) TABLE 28-2 Drugs of Choice in the Treatment of Constipation • Treat the underlying cause of constipation first if possible. Start treatment for constipation immediately if it is causing significant discomfort. By understanding the underlying cause of the constipation, the clinician will be better prepared to choose the class of laxative that is most likely to be successful. For example, constipation caused by diseases such as hypothyroidism should be resolved with treatment for hypothyroidism. • First, adequate fluids are crucial both for laxatives to work and to prevent constipation, with 1500 ml/day minimum essential for maintaining normal bowel activity. Adequate fluids act by keeping fluid in the feces as it passes through the colon. This maintains the bulk of the feces and allows for normal transit. Fluids that are diuretics, such as those that contain caffeine, do not work as well to keep water in the feces. Flavored waters are often an acceptable substitute for plain water. However, data are lacking to support that an increase in fluids to greater than 1500 ml/day is effective in alleviating constipation. • Second, a high-fiber diet is important. An adult should have a daily intake of 20 to 35 g of fiber; a child should receive 1 g per year of age plus 5 g/day after 2 years of age. This fiber is best obtained from high-roughage foods like bran or vegetables and fruits. See Table 28-3 for a list of foods that are high in fiber. Bran is the outer coating of various grains. The two most commonly found grains are wheat bran and oat bran, which have large amounts of fiber. Other whole grain, unpolished grains, and rice have the outer coating still on, have good amounts of fiber, and may be easier to tolerate than concentrated bran. Sudden increases in fiber in the diet can cause bloating and gas. A high-fiber diet is better tolerated if the change is made gradually. Enough fiber can also be obtained through the regular use of bran slurry (see Box 28-1 for ingredients). Start with 1 tablespoon a day and work up to 3 tablespoons twice a day as needed. It can be mixed with cereal or other foods. Make sure the patient continues to drink enough fluids. TABLE 28-3 • Third, patients should establish and maintain a regular exercise schedule. Any type of activity is helpful. Simply walking briskly every day facilitates digestion and keeps muscles of the body better toned. • Fourth, a regular toileting schedule should be established. This includes going to the toilet at the same time each day, 15 to 45 minutes after a meal. Patient should allow for 10 to 15 minutes on the toilet without interruption, stress, or the need to hurry. Patients should not ignore or postpone the urge to defecate. • Fluids, fiber, and exercise, which help most people, are not applicable to the very aged, the frail elderly, and those wheelchair- or bed-bound. Other individuals with CHF are unable to tolerate these mechanisms. It is essential for clinicians to know their patients and assess what is reasonable for them to do. Pharmacologic treatment may be added if nonpharmacologic treatment is not sufficient, or when immediate or thorough cleansing is indicated. Selection is based on matching the patient characteristics to the effects of the different categories of laxatives. Important factors that should be considered include the cause of constipation, long- or short-term use, severity of constipation, age of the patient, oral food and fluid intake, and prior laxative use (see Table 28-2). Polyethylene glycol and lactulose are recognized as highly effective. • Short-term constipation, whether occasional or caused by external factors, is treated with a short-acting laxative. Another short-term use for laxatives involves preparation for surgery or another procedure. • Mild short-term constipation can be treated with bulk laxatives or a saline agent such as Milk of Magnesia. • If the patient is severely constipated or has not responded to increased fiber intake, he might need an enema or one of the more potent laxatives. Saline laxatives such as Milk of Magnesia are suggested as second-line treatment by the AGA. Enemas are useful when the patient has stool in the rectum but is unable to push it out. If the patient is impacted, he must be manually disimpacted before any laxative is used. Stimulant laxatives are used for constipation that occurs higher in the colon and should be considered third-line agents. • If the patient has chronic constipation with a short-term exacerbation, long-term management will be necessary.

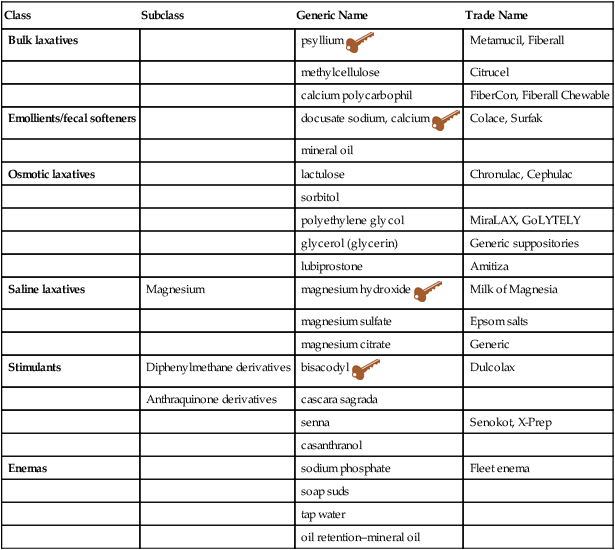

Laxatives

Class

Subclass

Generic Name

Trade Name

Bulk laxatives

psyllium ![]()

Metamucil, Fiberall

methylcellulose

Citrucel

calcium polycarbophil

FiberCon, Fiberall Chewable

Emollients/fecal softeners

docusate sodium, calcium ![]()

Colace, Surfak

mineral oil

Osmotic laxatives

lactulose

Chronulac, Cephulac

sorbitol

polyethylene glycol

MiraLAX, GoLYTELY

glycerol (glycerin)

Generic suppositories

lubiprostone

Amitiza

Saline laxatives

Magnesium

magnesium hydroxide ![]()

Milk of Magnesia

magnesium sulfate

Epsom salts

magnesium citrate

Generic

Stimulants

Diphenylmethane derivatives

bisacodyl ![]()

Dulcolax

Anthraquinone derivatives

cascara sagrada

senna

Senokot, X-Prep

casanthranol

Enemas

sodium phosphate

Fleet enema

soap suds

tap water

oil retention–mineral oil

Therapeutic Overview

Anatomy and Physiology

Disease Process

Agents

Example

Analgesics

codeine

morphine

Prostaglandin inhibitors

Antacids

Aluminum hydroxide

Calcium carbonate

Anticholinergics

Antidepressants

Antihistamines

Antiparkinson drugs

Antipsychotics

Antispasmodics

Anxiolytics

Other

Anticonvulsants

Antihypertensives

Barium sulfate

Iron

Lead

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors

Polystyrene resins verapamil

Treatment Principles

Standardized Guidelines

Evidence-Based Recommendations

Cardinal Points of Treatment

Short Term

Long Term

First line

Mild: bulk

Bulk

Second line

Severe: enema

Osmotic (saline class)

Third line

Stimulants

Stimulants

Nonpharmacologic Treatment

Type of Food

Examples

Fruits (most fruits contain fiber, especially those listed)

Apples

Blackberries

Peaches

Pears

Raspberries

Strawberries

Grains

Bran cereals

Brown rice

Popcorn

Rye bread

Whole wheat bread

Vegetables (most vegetables have fiber; the ones listed are especially high in fiber content)

Beans

Broccoli

Cabbage

Carrots

Cauliflower

Celery

Corn

Peas

Potatoes

Squash

Pharmacologic Treatment

Management

Short Term

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Laxatives

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue