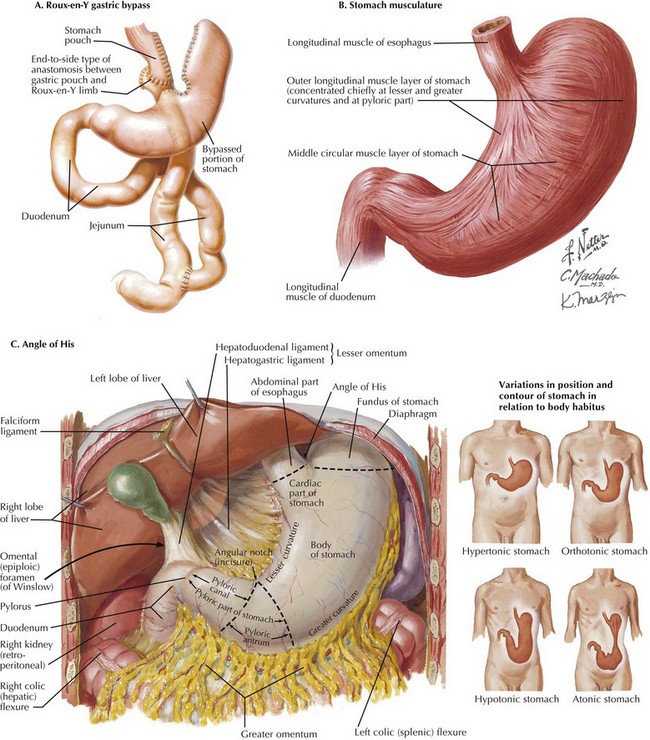

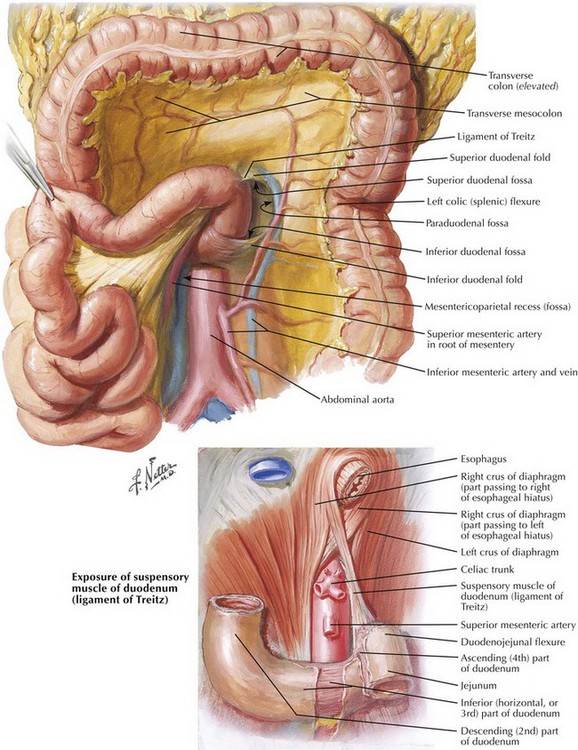

Chapter 11 Gastric bypass is the most common bariatric procedure. It has two components, restrictive and malabsorptive, which are both demonstrated in the depiction of a Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (Fig. 11-1, A). Because these patients are by definition morbidly obese, the excessive intraabdominal fat can make identification of the anatomy difficult. This chapter describes the anatomic landmarks during Roux-en-Y gastric bypass procedure. The restrictive component of gastric bypass depends on manufacture of a constricted, vertically oriented 20-mL gastric pouch, based on the lesser curvature of the stomach. The lesser curvature musculature is thick and less likely to distend than the fundus of the stomach (Fig. 11-1, B). Identification and dissection of the angle of His (the angle between the fundus and abdominal esophagus) is a crucial step during construction of the gastric pouch. The angle of His is just to the left of the midline and the gastroesophageal fat pad of Belsey. Transection of the stomach at the angle of His will separate the gastric fundus from the gastric pouch, because the gastric fundus can distend, with resultant weight gain (Fig. 11-1, C). This approach also avoids stapling of the esophagus. The ligament of Treitz is identified to the left of midline, with the inferior mesenteric vein to its left (Fig. 11-2). On creating a retrocolic path for the Roux limb, a defect in the transverse mesocolon must be anterior and to the left of ligament of Treitz to avoid injury to the middle colic vessels and to the pancreas.

Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass

Surgical Anatomy

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Basicmedical Key

Fastest Basicmedical Insight Engine