http://evolve.elsevier.com/McCuistion/pharmacology

Drugs for Pain Control During Labor

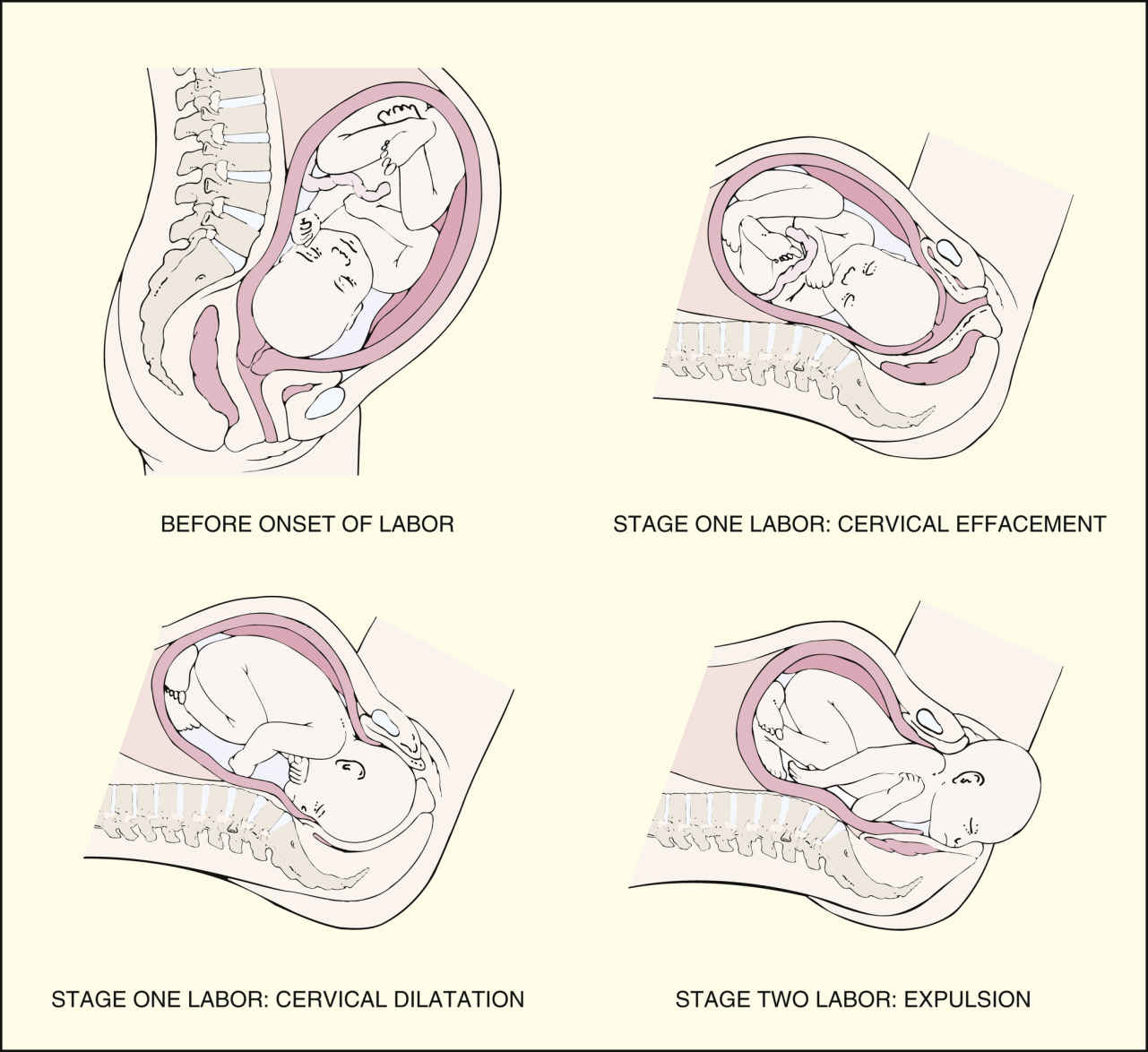

Labor and delivery are divided into four stages. During the first stage, the dilating stage, cervical effacement and dilation occur; the cervix thins and becomes fully dilated at 10 cm. The first stage consists of three phases categorized by cervical dilation: the latent phase (0 to 4 cm), the active phase (4 to 7 cm), and the transition phase (8 to 10 cm). The second stage of labor, the pelvic stage, begins with complete cervical dilation and ends with delivery of the newborn (Fig. 50.1). During the third stage of labor, placental separation and expulsion, the placenta separates from the uterine wall and is delivered. The fourth stage of labor, early postpartum, comprises the first 4 hours after the delivery of the placenta, and is a period of physiologic stabilization for the mother and initiation of familial attachment.

During the first stage of labor, uterine contractions produce progressive cervical effacement and dilation. As the first stage of labor progresses, uterine contractions become stronger, longer, and more frequent, and discomfort increases. Pain and discomfort in labor are caused by uterine contraction, cervical dilation and effacement, hypoxia of the contracting myometrium, and perineal pressure from the presenting part. Pain perception is influenced by physiologic, psychological, social, and cultural factors—in particular, the woman’s past experiences with pain, anticipation of pain, fear and anxiety, knowledge deficit of the labor and delivery process, and involvement of support persons.

Before administering pharmacologic treatment, nonpharmacologic measures should be initiated. Nonpharmacologic measures for pain relief during labor include (1) ambulation, (2) effleurage and counterpressure, (3) touch and massage, (4) changing positions and rocking, (5) engaging support persons, (6) breathing and relaxation techniques, (7) transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, (8) application of heat and cold, (9) aromatherapy, and (10) hydrotherapy (warm-water baths or showers).

Other nonpharmacologic measures include alternative and complementary drugs. Of particular concern is the use of herbal supplements by the pregnant patient later in pregnancy to stimulate labor. For example, some women ingest pregnancy toner tea, which includes raspberry, nettle, dandelion, alfalfa, and peppermint leaf. Other herbal supplements used include blue cohosh, castor oil, and evening primrose oil. Pregnant patients may self-administer, or the practice may be part of their traditional beliefs and framework of health. Concerns with herbal supplements are related to the often numerous physiologically active components of the herbs, adulterants, inconsistent dosing, and lack of proven efficacy. Herbs taken in late pregnancy may contribute to preterm labor or increased bleeding during delivery. Nurses must be culturally sensitive to the use of herbal supplements and health practices during pregnancy, specifically in the later gestational weeks.

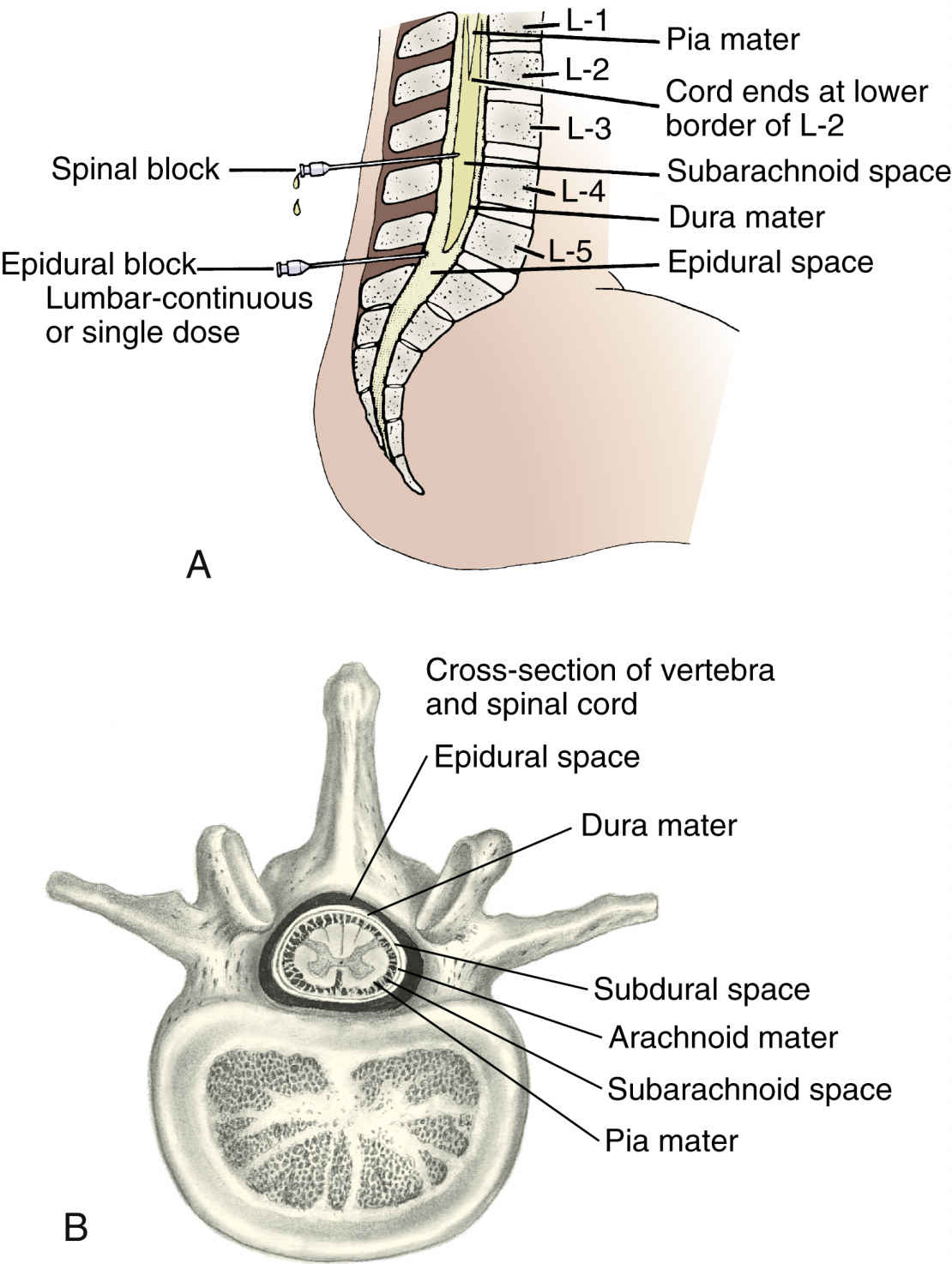

When pharmacologic intervention is needed for pain relief, drugs are used as an adjunct to nonpharmacologic measures. Drugs should be selected not only to decrease the patient’s pain but also to minimize side effects for the patient and the fetus or neonate. Pain relief in labor can be obtained with systemic analgesics and regional anesthesia, injection of drug near the nerves or spinal canal to numb a specific area of the body (Fig. 50.2). Analgesics alter the patient’s perception and sensation of pain without producing unconsciousness.

Analgesia and Sedation

Systemic drugs used during labor include sedative-hypnotics, narcotic agonists, and mixed narcotic agonist-antagonists. Secobarbital, a sedative-hypnotic, is administered orally, whereas hydroxyzine is administered orally or intramuscularly. Intravenous (IV) use is considered contraindicated because hydroxyzine is a vesicant. Because of variable response and blood levels with intramuscular (IM) administration, pentobarbital is primarily given intravenously. These drugs should be administered at the onset of the uterine contraction because parenteral administration at the onset decreases neonatal drug exposure because blood flow is decreased to the uterus and fetus.

Table 50.1 lists the analgesics and sedatives commonly used during labor, delivery, and postpartum and their dosages, uses, and considerations.

The sedative-tranquilizer drugs are most commonly given for false or latent labor or with ruptured membranes without true labor. These drugs may also be administered to minimize maternal anxiety and fear, and although they promote rest and relaxation, they do not provide pain relief. The sedative drugs most commonly used are barbiturates or hypnotics (e.g., secobarbital sodium and pentobarbital sodium). Other drugs, such as hydroxyzine, can be given alone during early labor or in combination with narcotic agonists when the patient is in active labor. In addition to decreasing anxiety and apprehension, hydroxyzine potentiates the analgesic action of the opioids and minimizes emesis. Promethazine, also a phenothiazine derivative, has been noted in studies to impair the analgesic efficacy of opioids and is now only labeled for nausea and vomiting.

The second group of drugs given for active labor is the narcotic agonists. These drugs may be administered parenterally or via regional blocks. When administered with neuraxial anesthesia, a lower dose of anesthetic is required for effective pain relief, thereby minimizing side effects. These drugs interfere with pain impulses at the subcortical level of the brain. To effect pain relief, opioids interact with mu and kappa receptors; for example, morphine sulfate activates both mu and kappa receptors.

Of the narcotic agonists, meperidine is the most commonly prescribed synthetic opioid for pain control during labor. A second narcotic agonist used for pain relief during labor is fentanyl, a short-acting synthetic opioid best administered intravenously because of its short duration of action. Morphine sulfate may also be used for pain control in active labor, but it is less frequently used. High doses of opioids are required for effective labor analgesia when administered parenterally. Opioids are further discussed in Chapter 25.

The third group of systemic drugs used for pain relief in labor is opioids with mixed narcotic agonist-antagonist effects. These drugs exert their effects at more than one site and are often an agonist at one site and an antagonist at another. The two most commonly used narcotic agonist-antagonist drugs are butorphanol tartrate and nalbuphine. A primary advantage of these drugs is their dose-ceiling effect. This means additional doses do not increase the degree of maternal or neonatal respiratory depression, so there is less respiratory depression with these drugs than with opioids. The respiratory depression ceiling effect is believed to result from activation of kappa agonists and weak mu antagonists.

Adverse Reactions

Adverse effects of sedative-hypnotic drugs (secobarbital, pentobarbital) include paradoxically increased pain and excitability, lethargy, subdued mood, decreased sensory perception, and hypotension. Fetal and neonatal side effects include decreased fetal heart rate (FHR) variability and neonatal respiratory depression, sleepiness, hypotonia, and delayed breastfeeding with poor sucking response for up to 4 days.

Side effects of phenothiazine derivatives and antiemetic antihistamines (e.g., promethazine, hydroxyzine) include confusion, disorientation, excess sedation, dizziness, hypotension, tachycardia, blurred vision, headache, restlessness, weakness, and urinary retention with promethazine; drowsiness, dry mouth, dizziness, headache, blurred vision, dysuria, urinary retention, and constipation with hydroxyzine. Decreased FHR variability can occur, and the neonate can experience moderate central nervous system (CNS) depression, hypotonia, lethargy, poor feeding, and hypothermia.

The adverse effects of opioids depend on the responses activated by the mu and kappa receptors. Activation of mu receptors results in analgesia, sedation, euphoria, decreased gastrointestinal (GI) motility, respiratory depression, and physiologic dependence. Activation of kappa receptors results in analgesia, decreased GI motility, miosis, and sedation. When parenterally administered, the side effects of opioids include nausea, vomiting, sedation, orthostatic hypotension, pruritus, and maternal and neonatal respiratory depression. The associated nausea and vomiting result from stimulation of the chemoreceptor trigger zone in the medulla. Motor block is another concern; mothers may not walk after delivery until they are able to maintain a straight leg raise against downward pressure applied by the practitioner. Fetal and neonatal effects include decreased FHR variability, depression of neonatal respirations, and depression of neonatal neurobehavior. For example, neonatal respiratory depression occurs within 2 to 3 hours after administering meperidine and may require reversal by administration of naloxone. Through inhibition of both mu and kappa receptors, naloxone may reverse the effects of opioids. It is important to note that with maternal administration of naloxone, there will be a subsequent increase in pain.

Narcotic agonist drugs (e.g., morphine, fentanyl) can cause orthostatic hypotension, nausea, vomiting, headache, sedation, hypotension, and confusion. Decreased FHR variability and neonatal CNS depression can occur with meperidine.

Mixed narcotic agonist-antagonist drugs (e.g., butorphanol tartrate, nalbuphine) can cause nausea, clamminess, sweating, sedation, respiratory depression, vertigo, lethargy, headache, and flush. Side effects in the fetus and neonate include decreased FHR variability, moderate CNS depression, hypotonia at birth, and mild behavioral depression.

Anesthesia

Anesthesia in labor and delivery represents the loss of painful sensations with or without loss of consciousness. Two types of pain are experienced in childbirth, visceral and somatic. Visceral pain from the cervix and uterus is carried by sympathetic fibers and enters the neuraxis at the thoracic (T10-T12) and lumbar (L1) spinal levels, and early labor pain is transmitted to T11 and T12 with later progression to T10 and L1. Somatic pain is caused by pressure of the presenting part and by stretching of the perineum and vagina. This is the pain of the transition phase and the second stage of labor, and it is transmitted to the sacral (S2-S4) areas by the pudendal nerve. Table 50.2 lists the anesthetics used during labor and delivery and their dosages, uses, and considerations.

Regional Anesthesia

Regional anesthesia achieves pain relief during labor and delivery without loss of consciousness. Injected local anesthetic agents temporarily block conduction of painful impulses along sensory nerve pathways to the brain. Regional anesthesia allows the patient to experience labor and childbirth with relief from discomfort in the blocked area while maintaining consciousness. The two primary types of anesthesia are local anesthetics for local infiltration (e.g., episiotomy) and regional blocks (e.g., epidural, spinal). The most common types of peridural anesthesia are spinal, epidural, and combined spinal-epidural blocks. Other less commonly administered regional blocks include caudal, paracervical, and pudendal blocks. The anesthesiologist or nurse anesthetist is responsible for administering regional anesthesia. Nurses may assist with administration of anesthesia, and they monitor the patient for drug effectiveness and side effects during and after administration.

TABLE 50.2

Anesthetic Used in Obstetrics†

| Drug | Route and Dosage | Uses and Considerations |

| Chloroprocaine | Lumbar epidural block: 2% or 3%, 2 to 2.5 mL per segment; usual start volume is 15-25 mL; max: single dose (with epinephrine 1:200,000), 14 mg/kg; total dose, 750 mg | An ester-type local anesthetic that stabilizes the neuronal membranes and prevents initiation and transmission of nerve impulses, affecting local anesthetic actions (local or pudendal block) Duration: Up to 60 min. Pregnancy category C∗; PB: UK; t½: 21-25 sec |

| Tetracaine 0.2%, 0.3% | Spinal anesthesia: Lower abd: 9-12 mg of 0.3% Perineum: 3-6 mg of 0.3% Saddle block: 2-4 mg of 0.2%; max: 15 mg Other anesthesia dosages available. | An ester-type local anesthetic that blocks both initiation and conduction of nerve impulses by decreasing neuronal membrane permeability to sodium ions; a low spinal block or spinal anesthesia for cesarean delivery Pregnancy category C∗; PB: UK; t½: UK |

| Lidocaine injectable | 50-75 mg of 5% solution; max: 4 mg/kg/dose or 300 mg per procedure when used without epinephrine | Suppresses automaticity of conduction tissue by increasing the electrical stimulation threshold of the ventricle; blocks both initiation and conduction of nerve impulses by decreasing neuronal membrane permeability to sodium ions Onset: 45-90 s; duration: 10-20 min. Pregnancy category B∗; PB 60%-80%; t½: 1.5-2 h |

| Bupivacaine | Epidural block: 3-4 mL increments IV or intrathecal administration of 10-20 mL of 0.25% or 0.5% The 0.75% concentration is not recommended for obstetric anesthesia; reports of cardiac arrest with difficult resuscitation and death have been reported. | Epidural or spinal for labor and cesarean delivery; blocks both initiation and conduction of nerve impulses by decreasing neuronal membrane permeability to sodium ions Onset: Up to 17 min; duration: epidural, 2-7.7 h; spinal, 1.5-2.5 h. Pregnancy category C∗; PB: 84%-95%; t½: 2.7 h |

| Ropivacaine | Lumbar epidural block for cesarean section: 20-30 mL dose of 0.5% solution or 15-20 mL of 0.75% solution in incremental doses Doses available for vaginal obstetric anesthesia as incremental administration or continuous infusion. | Epidural for cesarean delivery; blocks both initiation and conduction of nerve impulses by decreasing neuronal membrane permeability to sodium ions Onset: 3-15 min; duration: 3-15 h. Pregnancy category C∗; PB: UK; t½: 5-7 h |

Women receiving parenteral analgesic for labor and delivery may require more focused anesthesia for episiotomies and repair of perineal lacerations. Local anesthetic drugs may be administered alone, and the anesthetic drug primarily administered is lidocaine. Burning at the site of injection is the most common side effect.

Spinal anesthesia, also known as a saddle block, is injected in the subarachnoid space at the T10 to S5 dermatome. This anesthesia may be administered as a single dose or as a combined spinal-epidural block. Spinal anesthesia is administered immediately before delivery or late in the second stage, when the fetal head is on the perineal floor. Drugs frequently administered either alone or in combination with the local anesthetic for a vaginal delivery include bupivacaine with fentanyl. Dosages vary depending on whether administration of the anesthetic agent is plain or with epinephrine. Bupivacaine 0.75% concentration is not recommended for obstetric anesthesia due to reports of cardiac arrest with difficult resuscitation or death. Spinal anesthesia has a rapid onset, requires less local anesthetic, and may be used with high-risk patients. Postdural puncture headache is a primary concern and occurs 6 to 48 hours after dural puncture; it may also occur after accidental dural puncture with epidural anesthesia. Treatment for postdural headache includes analgesics, increased fluids, and bed rest. An epidural blood patch is the most effective means to treat postdural headache.

Lumbar epidurals may be administered as a single injection, by intermittent injection, as continuous patient-controlled epidural anesthesia (PCEA), or as a combined spinal-epidural block. Epidurals may be administered as a single anesthetic drug or with opioids or epinephrine. Most frequently, patients now receive a continuous epidural infusion, which provides more consistent drug levels and more effective pain relief. Rescue doses are given as necessary to achieve pain relief.

Opioids are administered with the local anesthetic to more effectively control the somatic pain of transition and second-stage labor. The opioids most frequently used in combination with the local anesthetic (bupivacaine, ropivacaine) are fentanyl or sufentanil, lipophilic opioids commonly used with continuous or patient-controlled epidural; these opioids offer rapid analgesia and fewer side effects than hydrophilic opioids. In contrast, morphine sulfate and hydromorphone are hydrophilic opioids, which have a slower onset of action, variable duration, and increased side effects, specifically respiratory depression (Table 50.2).

Another additive to the local anesthetic is epinephrine, which increases the duration of the local anesthetic, decreases its uptake and clearance from the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and enhances the intensity of the neural blockade. Single and intermittent injections have wide variations in drug levels and provide less effective control of pain. A continuous lumbar epidural allows a more evenly spaced drug level; less anesthetic is required to provide more effective pain control. Continuous-infusion PCEA gives the patient better control of her anesthesia Often single and intermittent injections and PCEA will require rescue doses to improve analgesia.

Lastly, combined spinal-epidural analgesia couples the rapid analgesia and specificity of catheter placement of spinal anesthesia with the continuous infusion via catheter of epidural anesthesia, providing pain relief for later labor.

Controversy exists regarding the effect of regional analgesia, specifically epidurals, on the progress of labor. Some studies indicate no significant effect on labor, whereas other research has demonstrated a decreased maternal urge to push and increased length of labor.

Anesthesia for cesarean delivery may be general, spinal, or epidural. General anesthesia, although rarely used, may be necessary for emergency deliveries, when spinal or epidural anesthesia are contraindicated. It allows for rapid anesthesia induction and control of the airway. Before the administration of general anesthesia, antacids or other drugs that reduce gastric secretions are given to decrease gastric acidity. See Unit XIII: Gastrointestinal Drugs for more information on acid reducers. More commonly, spinal or epidural anesthesia is administered for cesarean births. Spinal anesthesia is the more common choice for cesarean delivery because of rapid onset, increased reliability, and improvement in spinal needle design (smaller gauge and shape [Sprotte needle]) with subsequent reduction in postdural headaches. With spinal anesthesia, the local anesthetic most commonly administered is bupivacaine with fentanyl; pain relief begins in 5 minutes and lasts for approximately 2 hours. Sufentanil or morphine may also be administered. With the additives, spinal anesthesia provides 18 to 24 hours of pain relief. For epidural inductions, the test dose of lidocaine with epinephrine—followed by administration of local anesthetics—is given. This is followed by a bolus or maintenance infusion with anesthetics with or without opioids and/or epinephrine to maintain maternal comfort. The nurse should assess the level of analgesia and motor block at least hourly. Monitor for complications, such as cardiovascular or central nervous system toxicity, postdural puncture headache, fetal bradycardia, or respiratory depression.