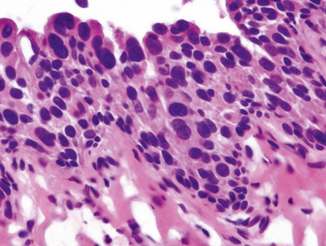

Fig. 19.1

Frozen section of a ureteral margin showing urothelium with reactive atypia associated with subepithelial edema and mild chronic inflammation. Slight, but uniform, nuclear enlargement is seen, but the nuclear polarity is maintained. Original magnification × 100

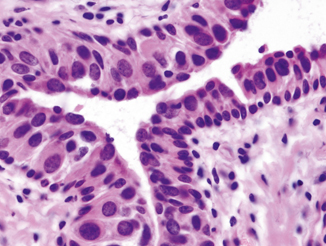

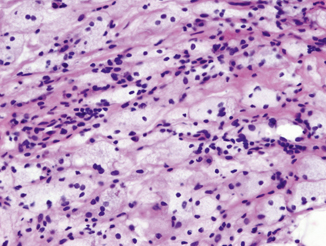

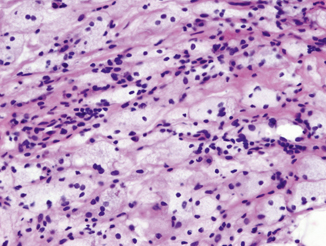

Fig. 19.2

Frozen section of a ureteral margin positive for urothelial carcinoma in-situ ( CIS). On frozen section, the most reliable criteria for diagnosis of urothelial CIS is marked cytologic atypia with nuclear enlargement, increased nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio, hyperchromasia, and frequent mitoses. Original magnification × 400

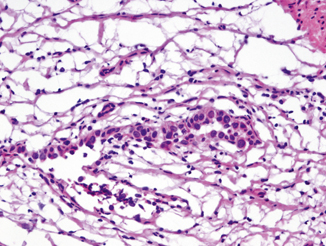

Fig. 19.3

Frozen section of the ureter showing largely denuded and attenuated urothelium with scattered in-situ carcinoma cells. Original magnification × 200

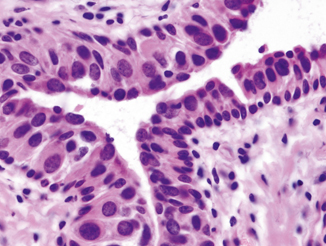

Because of retraction of the urethral mucosa, multiple levels of the specimen for intraoperative FSA may be necessary to identify the mucosa. The urothelium is often denuded due to intravesical therapy or intubation, special attention should be paid to the periurethral glands or ducts; pagetoid spread with a few high-grade malignant cells is sufficient for the diagnosis of urothelial CIS (Fig. 19.4).

Fig. 19.4

Frozen section of the urethra showing a prominent pagetoid spread of urothelial CIS characterized by individual large atypical tumor cells peculating in the urothelium. Notice the marked nuclear enlargement of tumor cells compared with the adjacent normal basal cells. Original magnification × 400

A biopsy of perivesical fat may be submitted for FSA to determine if there is extravesical extension or invasion of the tumor. Fat necrosis with associated fibrosis is not uncommonly seen, which is usually not too difficult to distinguish from carcinoma (Fig. 19.5). Reactive endothelial cells can sometimes be problematic, especially when they show cautery artifact. Thus, familiarity of preoperative diagnosis, intraoperative findings, and careful assessment of cytologic details are necessary for an accurate diagnosis.

Fig. 19.5

Frozen section of a nodule on the peritoneal surface of the bladder showing fat necrosis and plump endothelial cells which may mimic infiltrating carcinoma. Original magnification × 200

Assessment of Surgical Margins During Partial Cystectomy

Partial cystectomy , without a separate urinary diversion, is reserved for localized tumors, including solitary, primary urothelial carcinoma that does not involve specific regions of the bladder (e.g., trigone, bladder neck) and that can be resected with adequate (i.e., 1–2 cm) surgical margins. The classically described indication for partial cystectomy included carcinoma arising in a bladder diverticulum and urachal adenocarcinoma [4]. Partial cystectomy is also adequate for some high-risk patients and palliative situations. If it is done in properly selected patients, it has some advantages over radical cystectomy, such as the preservation of a functionally continent native urinary bladder and sexual potency in men.

The diagnosis of the bladder tumor is almost always established prior to cystectomy, and the purpose of intraoperative consultation is generally to evaluate surgical margins. This is an example that surgeon’s help in orientation of specimen is particularly critical. The margins should be inked, often with different colors when entire partial cystectomy specimen is submitted for FSA. How the sections are taken (i.e., parallel or perpendicular to the margins) is dependent on the gross findings. If a visible lesion is seen within 0.5 cm of the margin, it is advisable to take multiple serial sections perpendicular to that margin. Otherwise, sections may be taken parallel to the margin. Before taking sections parallel to the margin, tissue layers should be lined up so that all the layers could be visible in frozen section slides.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree