INTERMEDIATE- TO HIGH-GRADE SPINDLE CELL TUMORS

7.2 Dermatofibrosarcoma Protuberans

7.5 Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumor

7.6 Spindle Cell/Sclerosing Rhabdomyosarcoma

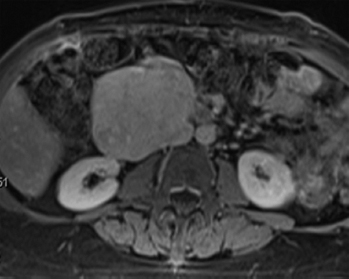

Leiomyosarcomas represent one of the most common malignancies of soft tissue; it is estimated that they comprise up to 25% of all sarcomas. Malignant smooth muscle tumors tend to occur preferentially in middle-aged and older adults, although rare cases have been documented in children. Leiomyosarcoma occurs in many locations, but is particularly common within the abdominal cavity (Figure 7.1.1). They occur in the retroperitoneum, pelvis, and in association with the large vessels, particularly the inferior vena cava. Extremity-based leiomyosarcoma is less common, with the deep soft tissues of the proximal thigh being a favored site. And finally, there are superficial leiomyosarcomas that arise in the dermal compartment of the skin.

Symptoms are related to the location of the lesion. Intra-abdominal tumors can reach very large size before they are clinically detected. More superficially based tumors tend to present earlier as mass lesions. Prognosis is directly related to tumor location, size, and histologic grade. In general, deep-seated lesions have a high incidence of recurrence and metastases. Prognosis for extremity-based lesions is somewhat more favorable.

There is a distinctive subset of malignant smooth muscle tumors that arise in immunocompromised hosts and are associated with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection. These neoplasms occur in individuals with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome as well as patients immunosuppressed in a posttransplant setting. The disease course in the EBV population appears to correlate with the immunosupression status of the host.

To date, molecular and cytogenetic analyses of leiomyosarcomas have revealed heterogeneous and complex genetic changes. Alterations of p53 and p16 are common but nonspecific findings. Recent gene expression profiling and array comparative hybridization data have demonstrated distinctive molecular subtypes that appear to have some prognostic predictive significance for patients. Targeted therapies have yet to come to fruition.

HISTOPATHOLOGY

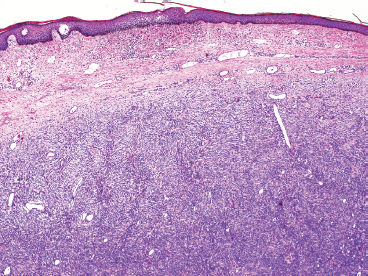

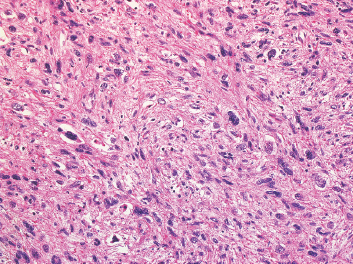

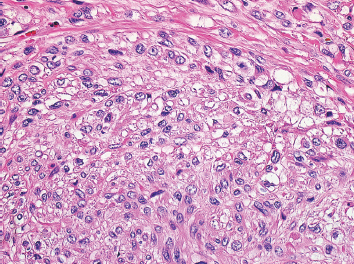

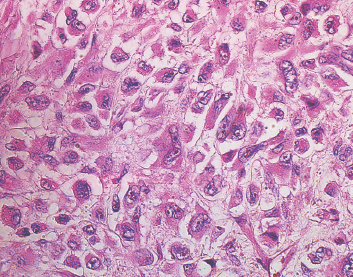

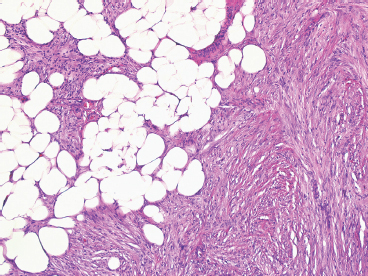

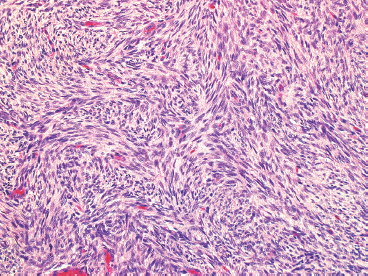

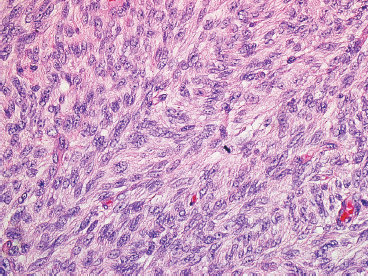

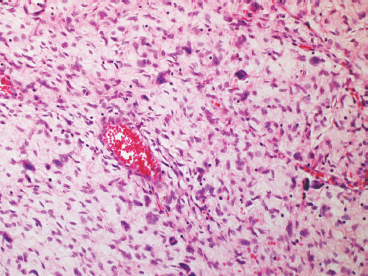

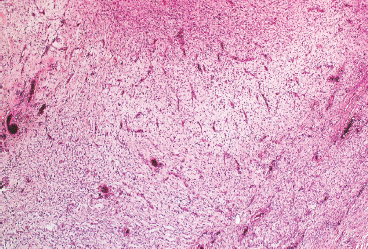

Leiomyosarcomas display a grade of histologic features that vary from minimal atypia (low-grade tumors) (Figure 7.1.2) to very high-grade, pleomorphic lesions with extensive hemorrhage and necrosis (Figure 7.1.3). Leiomyosarcomas tend to be arranged in whorls and fascicles of smooth muscle cells that appear to intersect each other at different angles. The tumors tend to be very hypercellular, but it is not unusual to have foci of hyalinization that result in hypocellular, fibrous regions. Individual tumor cells have abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and often show a distinctive perinuclear zone of clearing (Figure 7.1.4). Cytoplasmic boundaries are indistinct, and nuclei tend to be elongated with blunt nuclear ends. Mitotic figures are usually very conspicuous in leiomyosarcoma, and bizarre, atypical mitoses are frequently identified in higher-grade lesions.

The criteria for separation of benign leiomyoma and low-grade leiomyosarcoma have been described briefly in the leiomyoma section (Section 6.13). In short, criteria for malignancy will vary somewhat, depending on the location of the tumor. All lesions that display necrosis should be considered malignant. Lesions that demonstrate nuclear atypia and any mitotic activity should also probably be considered malignant. Lesions with greater than 5 mitoses per 50 high-power fields (hpf) should be considered malignant.

Some well-recognized variants of leiomyosarcoma deserve special mention. First is the so-called epithelioid type of leiomyosarcoma. This lesion is characterized by an abundance of large polygonal cells that have a more or less epithelial appearance (Figure 7.1.5). This can occasionally be a source of diagnostic confusion as leiomyosarcomas (of all types) are frequently immunohistochemically positive for broad-spectrum keratins. In addition, there is an inflammatory variant of leiomyosarcoma that tends to arise in the trunk and proximal extremities. This subtype shows heavy infiltration by chronic inflammatory cells, namely, lymphocytes. This lesion, although positive for desmin, may stain negatively for smooth muscle actin. And finally, some authors distinguish a pleomorphic type of leiomyosarcoma that tends to resemble undifferentiated high-grade sarcoma. This type is characterized by a very pleomorphic and anaplastic tumor cell population, often with an admixed spindle cell component. This lesion is discussed and illustrated in the section on pleomorphic myogenic tumors (Section 13.3).

CYTOLOGIC FINDINGS

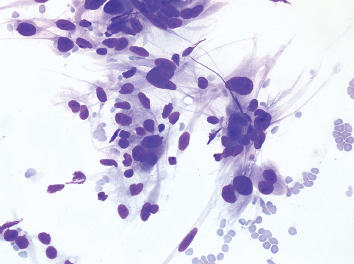

Fine needle aspiration (FNA) of leiomyosarcoma usually results in cellular aspirates. Unlike aspirates of other high-grade sarcomas, the cellular population in leiomyosarcoma tends to appear as loose aggregates with relatively few intact, detached cells in the background (Figure 7.1.6). Stripped tumor cell nuclei, on the other hand, are frequently identified. The tumor cell cytoplasm tends to be wispy in appearance and can occasionally show vacuolization. Nuclear features of leiomyosarcoma vary according to the grade of the lesion.

FIGURE 7.1.1 A large leiomyosarcoma associated with the renal vein. Leiomyosarcomas are common in the abdomen and retroperitoneum, where they arise from the large vessels.

FIGURE 7.1.2 Leiomyosarcoma is one of the few sarcomas that are subdivided into high- and low-grade lesions. This example of a low-grade leiomyosarcoma, aside from moderate nuclear atypia, resembles a leiomyoma.

FIGURE 7.1.3 A high-grade leiomyosarcoma with more obvious nuclear pleomorphism and atypia.

FIGURE 7.1.4 Leiomyosarcomas often show a distinctive perinuclear clearing. This phenomenon is often best demonstrated when fascicles are seen in both parallel and perpendicular planes.

FIGURE 7.1.5 The so-called epithelioid variant of leiomyosarcoma is characterized by cells with polyhedral shapes and abundant cytoplasm.

FIGURE 7.1.6 An aspirate from a high-grade leiomyosarcoma showing a loosely cohesive collection of pleomorphic spindle cells.

7.2 Dermatofibrosarcoma Protuberans

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP) is a locally aggressive tumor with a high risk of recurrence. DFSP arises in the dermis and tends to extend into the adjacent subcutaneous soft tissues. It occurs most frequently in younger adults, and is most often located on the extremities or trunk. Rare examples have been documented in the head and neck region. DFSP tends to be a slow-growing tumor with a long preclinical course. It often starts out as an irregular plaque-like lesion, but eventually grows into a “protuberance” composed of multiple nodules of tumor.

In its conventional form, DFSP does not metastasize. Instead, there tends to be a high rate of local recurrence, up to 40%, particularly in association with an inadequate surgical excision. A subset of DFSP exhibits “fibrosarcomatous change” (discussed in the following), the presence of which is associated with a more adverse prognosis. In this instance, there is a small but significant risk of developing metastatic disease (10%–15%).

DFSP is one of the soft tissue tumors that is associated with a specific translocation t(17;22)(q22;q13). This translocation results in the fusion of the collagen type 1 alpha 1 (COL1A) gene with the platelet-derived growth factor beta chain (PDGFB) gene. The fusion product does not have an aberrant function, but results in the overexpression of PDGFB driven by the promoter of COL1A. Although the mainstay of treatment for DFSP is largely surgical, recurrent or difficult-to-excise tumors will also respond to tyrosine kinase inhibitors such as imatinib or sunitinib.

HISTOPATHOLOGY

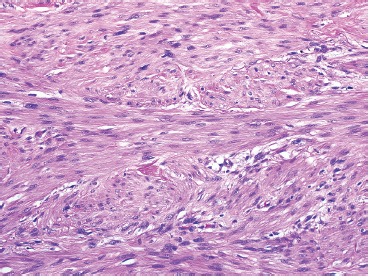

DFSP develops in the dermis, but remains separated from the overlying epidermis by a grenz zone, unless the lesion has ulcerated through the skin (Figure 7.2.1). It is poorly circumscribed and usually very infiltrative. One very useful diagnostic feature is the tendency of DFSP to infiltrate adjacent fat with thin extensions, often resulting in a “honeycomb” or “lace-like” appearance of the adjacent subcutaneous adipose tissue (Figure 7.2.2). DFSP is composed of a proliferation of small spindled cells with very poorly delineated cytoplasm. They are often arranged in a characteristic “pinwheel” or storiform type of pattern (Figure 7.2.3). The individual cells are largely monomorphic and are consistently small and spindled shaped. Mitotic activity is fairly low, with 5 or fewer mitoses per 10 high power fields (hpf).

There are several histologic variations of DFSP, which merit further discussion. The first is the presence of fibrosarcomatous-like areas within DFSP. As noted earlier, fibrosarcomatous DFSP is important to document because it is associated with more aggressive behavior. In this instance, the storiform arrangement is lost and is replaced by more of a herringbone-type configuration of tumor cells. In fibrosarcomatous foci, there may be more pronounced nuclear atypia, and the mitotic rate is high (often 10 to 20 mitoses per 10 hpf) (Figure 7.2.4). In addition, there may be foci of tumor necrosis, a finding that is not usually identified in conventional DFSP. CD34 immunohistochemical expression, which is usually strong and diffuse in DFSP, is often lost in the foci of fibrosarcomatous change.

Giant cell fibroblastoma represents an additional major histologic variant of DFSP. Once thought to be a completely separate tumor, it is now recognized as a true variant of DFSP because they share the same immunophenotype and translocation t(17;22). This subtype has a tendency to occur in children, but may occasionally occur in adults. Giant cell fibroblastoma contains large pseudovascular spaces and scattered multinucleate giant cells (Figure 7.2.5). The stroma tends to be less cellular than that of conventional DFSP, and there are often foci of marked myxoid change (Figure 7.2.6). Giant cell fibroblastomas also uniformly express CD34. Areas resembling giant cell fibroblastoma are a common finding in an otherwise conventional DFSP.

Other significant variations of DFSP include the presence of extensive myxoid stroma in the “myxoid dermatofibrosarcoma.” This pattern is rarely seen in pure form, but when present, can lead to confusion with a variety of other soft tissue lesions including myxoid liposarcoma, neurofibroma, or low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma (LGFS). Occasionally, DFSP shows prominent pigment in the form of melanin-containing dendritic cells. This form of DFSP is commonly referred to as Bednar tumor and is more common in individuals with heavily pigmented skin. Bednar tumor is cytogenetically identical to normal or conventional DFSP.

CYTOLOGIC FINDINGS

Aspirates of DFSP tend to be very cellular and are usually composed of both a cohesive population of cells as well as individual tumor cells. The cohesive fragments often involve a piece of matrix material, which is either metachromatic (on air-dried specimens) or fibrillar in appearance. The individual cell population is composed of mildly pleomorphic spindle to oval cells. Many individual cells are stripped of cytoplasm and appear as “naked nuclei.” Those that retain cytoplasm often have bipolar cytoplasmic processes. Cell nuclei tend to have smooth nuclear borders and finely dispersed chromatin.

The cytologic features of DFSP are not entirely specific, and a differential diagnosis would include many of the more cellular spindled lesions: synovial sarcoma (SS), solitary fibrous tumor, fibrosarcoma, and so on. However, in the appropriate clinical setting (a large, dermal-based protuberant mass) and positive immunohistochemical staining for CD34, a diagnosis of DFSP can be made with confidence.

FIGURE 7.2.1 Low-power view of Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP) arising in the dermis. The overlying epidermis is usually intact, and there is an uninvolved “grenz zone” between tumor and skin surface.

FIGURE 7.2.2 DFSP infiltrates widely and insidiously. It often spreads in a “lacelike” or honeycomb pattern into underlying fat.

FIGURE 7.2.3 On high power, the characteristic “pinwheel” or storiform pattern of DFSP is evident.

FIGURE 7.2.4 Fibrosarcomatous change within a DFSP is characterized by replacement of the storiform pattern with a “herringbone” type of pattern. In addition, there is an increase in mitotic activity and more nuclear atypia.

FIGURE 7.2.5 Giant cell fibroblastoma is a variant of DFSP that is distinguished by overall lower cellularity, presence of large vessels, and scattered multinucleate giant cells.

FIGURE 7.2.6 Giant cell fibroblastoma tends to have an edematous or myxoid appearance.

Infantile fibrosarcoma (IF), also known as congenital or juvenile fibrosarcoma, is a soft tissue-based fibrous proliferation that affects infants and young children exclusively. Over half of the cases are congenital, and almost all cases occur within the first 2 years of life. IF tends to occur on the extremity, but occasionally involves the chest, trunk, or head and neck region. These tumors grow rapidly and are often very large by the time the infant is seen clinically (Figure 7.3.1). They occasionally will cause surface ulceration of the overlying skin or can cause erosion of adjacent bone. If deep seated, IF can cause a number of serious and life-threatening complications including obstruction or mass effect on vital organs, bowel perforation, and meconium peritonitis.

On imaging, IF is nondescript but presents as a large soft tissue-based lesion, often with punctate calcifications. Unlike the adult form of fibrosarcoma, IF has a relatively good prognosis and tends to behave more like fibromatosis than a true fibrosarcoma. IF is considered a tumor of intermediate-grade malignancy. About one-third of cases of IF recur locally, with an increased incidence of recurrence in nonextremity-based sites. The metastasis rate is very low, estimated to be less than 5%. Treatment of IF tends to be surgical. In some instances, particularly in relatively inaccessible sites, neoadjuvant chemotherapy may be used in an effort to condense the tumor prior to definitive excision. Interestingly, there have been reports of spontaneous regression of IF.

The cytogenetic and molecular genetic features of IF are well characterized. IF is characterized by a translocation t(12;15), resulting in an ETV6-TRK3 gene fusion. This represents a diagnostically exploitable feature of IF (Figure 7.3.2). Of note, this translocation is also identified in the cellular variant of congenital mesoblastic nephroma of the kidney as well as in a handful of other tumors. In addition, the translocation is also often accompanied by gains in chromosomes 8,11,17, and 20.

HISTOPATHOLOGY

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree