Chapter 4 Infectious diseases, tropical medicine and sexually transmitted infections

Infection and infectious disease

In the developing world successes such as the eradication of smallpox have been balanced or outweighed by the new plagues. Infectious diseases cause nearly 25% of all human deaths (Table 4.1), rising to more than 50% in low income countries. Two billion people – one-third of the world’s population – are infected with tuberculosis (TB), up to 400 million people catch malaria every year and 200 million are infected with schistosomiasis. Some 500 million people are chronically infected with a hepatitis virus (either HBV or HCV) and 34 million people are living with HIV/AIDS, with 2.6 million new HIV infections in 2008 (65% in sub-Saharan Africa). Infections are often multiple and there is synergy both between different infections and between infection and other factors such as malnutrition. Many of the infectious diseases affecting developing countries are preventable or treatable, but continue to thrive owing to lack of money and political will.

Table 4.1 Worldwide mortality from infectious diseases

| Disease | Estimated deaths (annual) |

|---|---|

Acute lower respiratory infection | 3.5 million |

HIV/AIDS | 2 million |

Tuberculosis | 2 million |

Diarrhoeal disease | 1.8 million |

Malaria | 1 million |

Measles | 350 000 |

Whooping cough | 301 000 |

Tetanus | 292 000 |

Meningitis | 175 000 |

Leishmaniasis | 51 000 |

Trypanosomiasis | 10 000 |

Infectious agents

The causative agents of infectious diseases can be divided into four groups:

Other higher classes, notably the insects and the arachnids, also contain species which can parasitize man and cause disease: these are discussed in more detail on page 160.

Host–organism interactions

The symptoms and signs of infection are a result of the interaction between host and pathogen. In some cases, such as the early stages of influenza, symptoms are almost entirely due to killing of host cells by the invading organism. Usually, however, the harmful effects of infection are due to a combination of direct microbial pathogenicity and the body’s response to infection. In meningococcal septicaemia, for example, much of the tissue damage is caused by cytokines released in an attempt to fight the bacteria. The molecular mechanisms underlying host-pathogen interactions are discussed in more detail on page 78.

Sources of infection

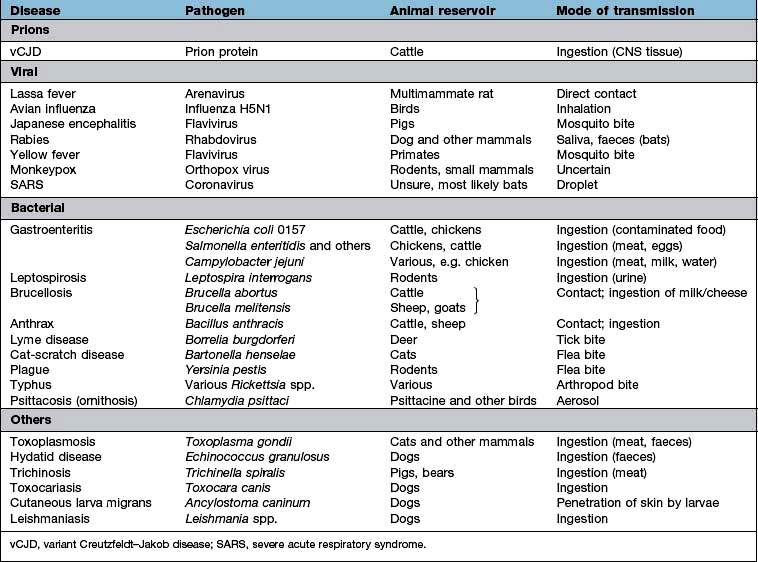

Zoonoses are infections that can be transmitted from wild or domestic animals to man. Infection can be acquired in a number of ways: direct contact with the animal, ingestion of meat or animal products, contact with animal urine or faeces, aerosol inhalation, via an arthropod vector or by inoculation of saliva in a bite wound. Many zoonoses can also be transmitted from person to person. Some zoonoses are listed in Table 4.2.

Most microorganisms do not have a vertebrate or arthropod host but are free-living in the environment. The vast majority of these environmental organisms are non-pathogenic, but a few can cause human disease (Table 4.3). Person-to-person transmission of these infections is rare. Some parasites may have a stage of their life cycle which is environmental (e.g. the free-living larval stage of Strongyloides stercoralis and the hookworms), even though the adult worm requires a vertebrate host. Other pathogens can survive for periods in water or soil and be transmitted from host to host via this route (see below): these should not be confused with true environmental organisms.

Table 4.3 Environmental organisms which can cause human infection

| Organism | Disease (most common presentations) |

|---|---|

Bacteria |

|

Burkholderia pseudomallei | Melioidosis |

Burkholderia cepacia | Lung infection in cystic fibrosis |

Pseudomonas spp. | Various |

Legionella pneumophila | Legionnaires’ disease (pneumonia) |

Bacillus cereus | Gastroenteritis |

Listeria monocytogenes | Various |

Clostridium tetani | Tetanus |

Clostridium perfringens | Gangrene, septicaemia |

Mycobacteria other than tuberculosis (MOTT) | Pulmonary infections |

Fungi |

|

Candida spp. | Local and disseminated infection |

Cryptococcus neoformans | Meningitis, pulmonary infection |

Histoplasma capsulatum | Pulmonary infection |

Coccidioides immitis | Pulmonary infection |

Mucor spp. | Mucormycosis (rhinocerebral, cutaneous) |

Sporothrix schenckii | Lymphocutaneous sporotrichosis |

Blastomyces dermatitidis | Pulmonary infection |

Aspergillus fumigatus | Pulmonary infections |

Routes of transmission

Many tropical infections, including malaria, are spread from person to person or from animal to person by an arthropod vector. Vector-borne diseases are also found in temperate climates, but are relatively uncommon. In most cases part of the parasite life cycle takes place within the body of the arthropod and each parasite species requires a specific vector. Simple mechanical transfer of infective organisms from one host to another can occur, but is rare. Some vector-borne diseases are shown in Table 4.4.

Table 4.4 Infections transmitted by arthropod vectors

| Vector | Disease | Microorganism |

|---|---|---|

Mosquito | Malaria | Plasmodium spp. |

Lymphatic filariasis | Wuchereria bancrofti, Brugia malayi | |

Yellow fever | Flavivirus | |

West Nile fever | Flavivirus | |

Dengue | Flavivirus | |

Sandfly | Leishmaniasis | Leishmania spp. |

Blackfly | Onchocerciasis | Onchocerca volvulus |

Tsetse fly | Sleeping sickness | Trypanosoma brucei |

Flea | Plague | Yersinia pestis |

Endemic typhus | Rickettsia typhi | |

Carrion’s disease | Bartonella bacilliformis | |

Reduviid bug | Chagas’ disease | Trypanosoma cruzi |

Louse | Epidemic typhus | Rickettsia prowazekii |

Louse-borne relapsing fever | Borrelia recurrentis | |

Hard tick | Lyme disease | Borrelia burgdorferi |

Typhus (spotted fever group) | Rickettsia spp. | |

Babesiosis | Babesia spp. | |

Tick-borne relapsing fever | Borrelia duttonii | |

Tick-borne encephalitis | Flavivirus | |

Congo-Crimean haemorrhagic fever | Nairovirus (Bunyavirus) |

Direct person-to-person spread

Organisms can be passed on directly in a number of ways. Sexually transmitted infections are dealt with on page 160. Skin infections such as ringworm, and ectoparasites such as scabies and head lice, can be spread by simple skin-to-skin contact. Other organisms are passed on by blood- (or occasionally other body fluid) to-blood transmission. Blood-to-blood transmission can occur during sexual contact, from mother to infant either transplacentally or in the peripartum, between intravenous drug users sharing any part of their injecting equipment, when infected medical or other (e.g. tattoo needles) equipment is reused, if contaminated blood or blood products are transfused, or in any sporting or accidental contact when blood is spilled. Ingestion of infected breast milk is another route of person-to-person spread for some infections (e.g. HIV).

Prevention and control

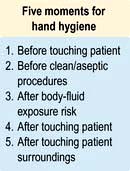

Infection control measures. Poor infection control practice in hospitals and other healthcare environments can cause the transfer of infection from person to person. This may be air-borne, via fomites or a direct contact route. It is essential that all healthcare workers wash or clean their hands before and after patient contact and whenever necessary they should wear gloves, aprons and other protective equipment. This is particularly necessary when performing invasive procedures, or manipulating indwelling devices such as cannulae.

Infection control measures. Poor infection control practice in hospitals and other healthcare environments can cause the transfer of infection from person to person. This may be air-borne, via fomites or a direct contact route. It is essential that all healthcare workers wash or clean their hands before and after patient contact and whenever necessary they should wear gloves, aprons and other protective equipment. This is particularly necessary when performing invasive procedures, or manipulating indwelling devices such as cannulae.

Eradication of reservoir. In a few diseases, for which man is the only natural reservoir of infection, it may be possible to eliminate disease by an intensive programme of case finding, treatment and immunization. This has been achieved in the case of smallpox. If there is an animal or environmental reservoir, complete eradication is unlikely, but local control methods may decrease the risk of human infection (e.g. killing of rodents to control plague, leptospirosis and other diseases).

Eradication of reservoir. In a few diseases, for which man is the only natural reservoir of infection, it may be possible to eliminate disease by an intensive programme of case finding, treatment and immunization. This has been achieved in the case of smallpox. If there is an animal or environmental reservoir, complete eradication is unlikely, but local control methods may decrease the risk of human infection (e.g. killing of rodents to control plague, leptospirosis and other diseases).

Classification of outbreaks

Person to person where infection is passed from one infected individual to another and outbreaks of infection are separated by the incubation period.

Person to person where infection is passed from one infected individual to another and outbreaks of infection are separated by the incubation period.

‘Point source’ is where there is a single source of infection, e.g. food eaten at a social function. All those infected will develop symptoms at the same time, around the expected incubation period.

‘Point source’ is where there is a single source of infection, e.g. food eaten at a social function. All those infected will develop symptoms at the same time, around the expected incubation period.

Common source where there is a single source of infection but over a period of time, e.g. a symptomatic carrier of infection working with food preparation. Many people will be exposed over a long period of time.

Common source where there is a single source of infection but over a period of time, e.g. a symptomatic carrier of infection working with food preparation. Many people will be exposed over a long period of time.

Epidemic. An increased unusual widespread infection in the community, causing waves of infection. These spread through communities and affect all people who have no active immunity to that infection.

Epidemic. An increased unusual widespread infection in the community, causing waves of infection. These spread through communities and affect all people who have no active immunity to that infection.

Cases of some infectious diseases should be notified to the public health authorities so that they are aware of cases and outbreaks. Diseases that are notifiable in England and Wales are listed in Table 4.5.

Table 4.5 Diseases notifiable (to Local Authority Proper Officers) in England and Wales, under the Health Protection (Notification) Regulations 2010

FURTHER READING

Cardo D, Dennehy PH, Halverson P et al. Moving toward elimination of healthcare-associated infections: a call to action. Am J Infect Control 2010; 38:671–675.

Chomel B, Belotto A, Meslin FX. Wildlife, exotic pets and emerging zoonoses. Emerg Infect Dis 2007; 13:6–11.

Horton R, Das P. Indian health: the path from crisis to progress. Lancet 2011; 377:181–183.

Relman DA. Microbial genomics and infectious diseases. N Engl J Med 2011; 365: 347–357.

Shurman EK. Global climate change and infectious disease. N Engl J Med 2010; 282:1061–1063.

Principles and basic mechanisms

Specificity

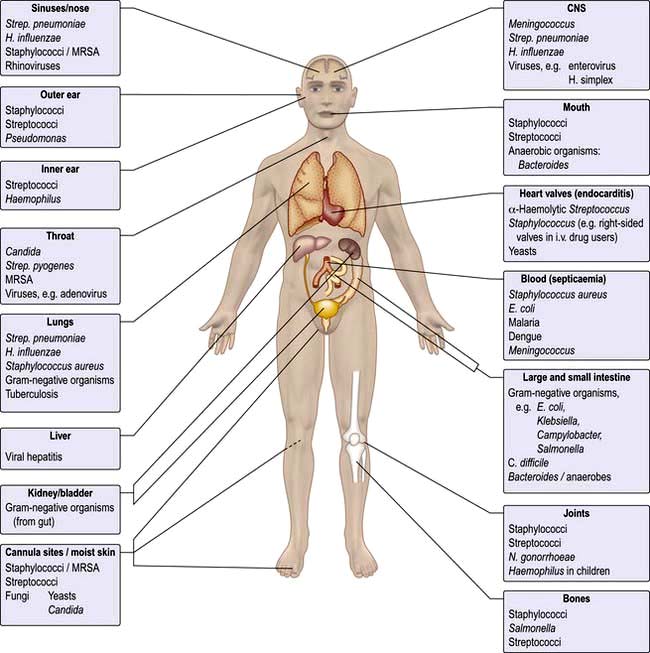

Microorganisms are often highly specific with respect to the organ or tissue they infect (Fig. 4.1). For example, a number of viruses are hepatotropic, such as those responsible for hepatitis A, B, C and E and yellow fever. This predilection for specific sites in the body relates partly to the presence of appropriate receptors on different cell types and partly to the immediate environment in which the organism finds itself; e.g. anaerobic organisms colonize the anaerobic colon, whereas aerobic organisms are generally found in the mouth, pharynx and proximal intestinal tract. Other organisms that show selectivity include:

Even within a species of bacterium such as E. coli, there are clear differences between strains with regard to their ability to cause gastrointestinal disease (see p. 110), which in turn differ from uropathogenic E. coli responsible for urinary tract infection.

Within an organ a pathogen may show selectivity for a particular cell type. In the intestine, for example, rotavirus predominantly invades and destroys intestinal epithelial cells on the upper portion of the villus, whereas reovirus selectively enters the body through the specialized epithelial cells, known as M cells that cover the Peyer’s patches (see p. 262).

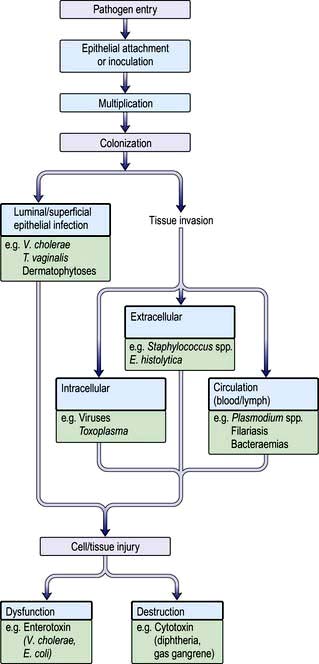

Pathogenesis

Figure 4.2 summarizes some of the steps that occur during the pathogenesis of infection. In addition, pathogens have developed a variety of mechanisms to evade host defences. For example, some pathogens produce toxins directed at phagocytes: Staphylococcus aureus (α-toxin), Streptococcus pyogenes (streptolysin) and Clostridium perfringens (α-toxin), while others such as Salmonella spp. and Listeria monocytogenes can survive within macrophages. Several pathogens possess a capsule that protects against complement activation (e.g. Strep. pneumoniae). Antigenic variation is an additional mechanism for evading host defences that is recognized in viruses (antigenic shift and drift in influenza), bacteria (flagella of salmonella and gonococcal pili) and protozoa (surface glycoprotein changes in Trypanosoma).

Epithelial attachment

Many bacteria attach to the epithelial substratum by specific organelles called pili (or fimbriae) that contain a surface lectin(s) – a protein or glycoprotein that recognizes specific sugar residues on the host cell. This family of molecules is known as adhesins (see p. 23). Following attachment, some bacteria, such as species of coagulase-negative staphylococci, produce an extracellular slime layer and recruit additional bacteria, which cluster together to form a biofilm. These biofilms can be difficult to eradicate and are a frequent cause of medical device-associated infections which affect prosthetic joints and heart valves as well as indwelling catheters. Many viruses and protozoa (e.g. Plasmodium spp., Entamoeba histolytica) attach to specific epithelial target-cell receptors. Other parasites such as hookworm have specific attachment organs (buccal plates) that firmly grip the intestinal epithelium.

Colonization

an intracellular location for the pathogen (e.g. viruses, Mycobacterium spp., Toxoplasma gondii, Plasmodium spp.)

an intracellular location for the pathogen (e.g. viruses, Mycobacterium spp., Toxoplasma gondii, Plasmodium spp.)

an extracellular location for the pathogen (e.g. pneumococci, E. coli, Entamoeba histolytica)

an extracellular location for the pathogen (e.g. pneumococci, E. coli, Entamoeba histolytica)

invasion directly into the blood or lymph circulation (e.g. schistosome schistosomula and trypanosomes).

invasion directly into the blood or lymph circulation (e.g. schistosome schistosomula and trypanosomes).

Tissue dysfunction or damage

Microorganisms produce disease by a number of well-defined mechanisms:

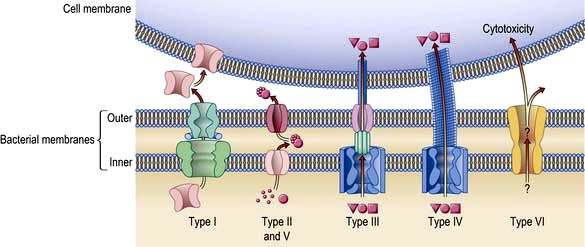

Exotoxins have many diverse activities including inhibition of protein synthesis (diphtheria toxin), neurotoxicity (Clostridium tetani and C. botulinum) and enterotoxicity, which results in intestinal secretion of water and electrolytes (E. coli, Vibrio cholerae). Colonization and secretion in many classical diarrhoeal diseases is the result of virulence-associated genes which encode protein secretion systems (Fig. 4.3).

Exotoxins have many diverse activities including inhibition of protein synthesis (diphtheria toxin), neurotoxicity (Clostridium tetani and C. botulinum) and enterotoxicity, which results in intestinal secretion of water and electrolytes (E. coli, Vibrio cholerae). Colonization and secretion in many classical diarrhoeal diseases is the result of virulence-associated genes which encode protein secretion systems (Fig. 4.3).

Endotoxin is a lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in the cell wall of Gram-negative bacteria. It is responsible for many of the features of septic shock (see p. 881), namely hypotension, fever, intravascular coagulation and, at high doses, death. The effects of endotoxin are mediated predominantly by release of tumour necrosis factor.

Endotoxin is a lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in the cell wall of Gram-negative bacteria. It is responsible for many of the features of septic shock (see p. 881), namely hypotension, fever, intravascular coagulation and, at high doses, death. The effects of endotoxin are mediated predominantly by release of tumour necrosis factor.

Staphylococcus aureus presents an excellent example of the repertoire of microbial virulence. The clinical expression of disease varies according to site, invasion and toxin production and is summarized in Table 4.6. Furthermore, host susceptibility to infection may be linked to genetic or acquired defects in host immunity that may complicate intercurrent infection, injury, ageing and metabolic disturbances (Table 4.7).

Table 4.6 Clinical conditions produced by Staphylococcus aureus

Table 4.7 Examples of host factors that increase susceptibility to staphylococcal infections (predominantly Staphylococcus aureus)

Host response to infection

Antibody and cell-mediated immune mechanisms play a vital role in combating infection. All organisms can initiate secondary immunological mechanisms, such as complement activation, immune complex formation and antibody-mediated cytolysis of cells. The immunological response to infection is described in Chapter 3.

Metabolic and immunological consequences of infection

Body temperature is controlled by the thermoregulatory centre in the anterior hypothalamus in the floor of the third ventricle. Body temperature is maintained at 36.8°C in health, with a diurnal variation of ±0.5°C. Gram-negative bacteria contain lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and peptidoglycan, which is also a component of Gram-positive bacterial cell walls. Toll-like receptors (TLR, see p. 55) on monocytes and dendritic cells recognize these lipopolysaccharides and generate signals leading to formation of inflammatory cytokines, e.g. IL-1, -6, -12, TNF-α and many others. These cytokines act on the thermoregulatory centre by increasing prostaglandin (PGE2) synthesis. The antipyretic effect of salicylates is brought about, at least in part, through its inhibitory effects on prostaglandin synthase.

The biological behaviour of the pathogen and the consequent host response are responsible for the clinical expression of disease that often allows clinical recognition. The incubation period following exposure can be helpful (e.g. chickenpox 14–21 days). The site and distribution of a rash may be diagnostic (e.g. shingles), while symptoms of cough, sputum and pleuritic pain point to lobar pneumonia. Fever and meningismus characterize classical meningitis. Infection may remain localized or become disseminated and give rise to the sepsis syndrome and disturbances of protein metabolism and acid–base balance (see Ch. 16). Many infections are self-limiting and immune and non-immune host defence mechanisms will eventually clear the pathogens. This is generally followed by tissue repair, which may result in complete resolution or leave residual damage.

FURTHER READING

Eltzschig HK, Carmeliet P. Hypoxia and inflammation. N Engl J Med 2011; 364:656–665.

Fey PD, Olson ME. Current concepts in biofilm formation of Staphylococcus epidermidis. Future Microbiol 2010; 5:917–933.

Lemichez E, Lecuit M, Nassif X et al. Breaking the wall: targeting of the endothelium by pathogenic bacteria. Nat Rev Microbiol 2010; 8:93–104.

Yahr TL. A critical new pathway for toxin secretion? N Engl J Med 2006; 355:1171–1172.

Approach to the patient with a suspected infection

History

Travel history: some diseases are more prevalent in certain geographical locations and many infections common in the tropics are seen rarely, if at all, in the UK.

Travel history: some diseases are more prevalent in certain geographical locations and many infections common in the tropics are seen rarely, if at all, in the UK.

Food and water history: systemic as well as gastroenteric infections can be caught via this route.

Food and water history: systemic as well as gastroenteric infections can be caught via this route.

Animal contact: domestic, farm and wild animals can all be responsible for zoonotic infection.

Animal contact: domestic, farm and wild animals can all be responsible for zoonotic infection.

Sexual activity: as well as the traditional sexually transmitted diseases, HIV, hepatitis B and occasionally other blood-borne infections can be transmitted sexually. Some enteric infections are more common among men who have sex with men.

Sexual activity: as well as the traditional sexually transmitted diseases, HIV, hepatitis B and occasionally other blood-borne infections can be transmitted sexually. Some enteric infections are more common among men who have sex with men.

Intravenous drug use: as well as blood-borne viruses, drug injectors are susceptible to a variety of bacterial and fungal infections due to inoculation. Other needle exposures, such as tattooing and body piercing and receipt of blood products (especially outside the UK), are also risk factors for blood-borne viruses.

Intravenous drug use: as well as blood-borne viruses, drug injectors are susceptible to a variety of bacterial and fungal infections due to inoculation. Other needle exposures, such as tattooing and body piercing and receipt of blood products (especially outside the UK), are also risk factors for blood-borne viruses.

Leisure activities: certain pastimes may predispose to water-borne infections or zoonoses.

Leisure activities: certain pastimes may predispose to water-borne infections or zoonoses.

Clinical examination

A thorough examination covering all systems is required. Skin rashes and lymphadenopathy are common features of infectious diseases and the ears, eyes, mouth and throat should also be inspected. Infections commonly associated with a rash are listed in Box 4.1. Rectal, vaginal and penile examination is required in sexually transmitted infections. The fever pattern may occasionally be helpful, e.g. the tertian fever of falciparum malaria, but too much weight should not be placed on the pattern or degree.