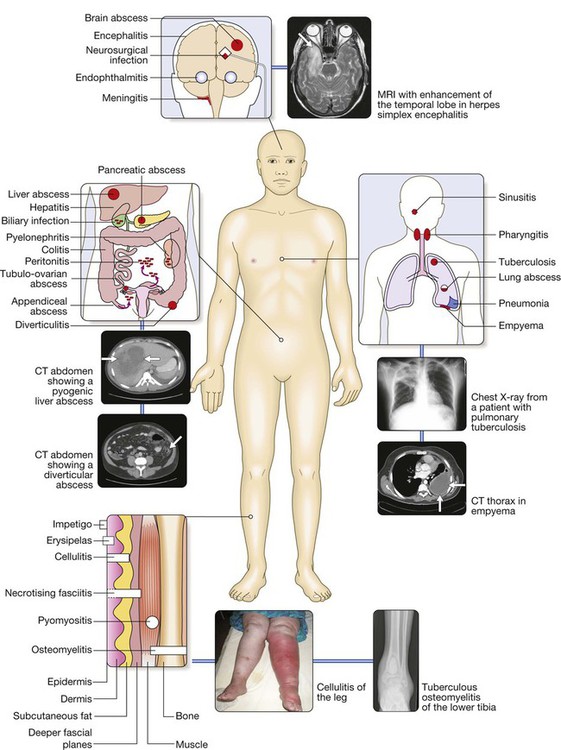

• Documentation of fever. ‘Feeling hot’ or sweaty does not necessarily signify fever. Fever is diagnosed only when a body temperature of over 38.0°C has been recorded. Axillary and aural measurement is less accurate than oral or rectal. Outpatients may be trained to keep a temperature chart. • Rigors. Shivering (followed by excessive sweating) occurs with a rapid rise in body temperature from any cause. • Night sweats. These are associated with particular infections (e.g. tuberculosis, infective endocarditis), but sweating from any cause is worse at night. • Excessive sweating. Alcohol, anxiety, thyrotoxicosis, diabetes mellitus, acromegaly, lymphoma and excessive environmental heat all cause sweating without temperature elevation. • Recurrent fever. There are various causes, e.g. Borrelia recurrentis, bacterial abscess. • Accompanying features. Headache. Severe headache and photophobia, although characteristic of meningitis, may accompany other infections. Delirium. Mental confusion during fever is more common in young children or the elderly. Muscle pain. Myalgia may occur with viral infections, such as influenza, and with septicaemia, including meningococcal sepsis. Shock. Shock may accompany severe infections and sepsis (Ch. 8). The principles of infection and its investigation and therapy are described in Chapter 6. This chapter and the following ones on human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) and sexually transmitted infection (STI) describe the approach to patients with potential infectious disease, the individual infections and the resulting syndromes. ‘Fever’ implies an elevated core body temperature of more than 38.0°C (p. 138). Fever is a response to cytokines and acute phase proteins (pp. 74 and 82) and occurs in infections and in non-infectious conditions. • a full blood count (FBC) with differential, including eosinophil count • urea and electrolytes, liver function tests (LFTs), blood glucose and muscle enzymes • inflammatory markers, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) • a test for antibodies to HIV-1 (p. 392) • autoantibodies, including antinuclear antibodies (ANA) • chest X-ray and electrocardiogram (ECG) • urinalysis and urine culture • other specimens, as indicated by history and examination, e.g. wound swab; sputum culture; stool culture, microscopy for ova and parasites, and Clostridium difficile toxin assay; if relevant, malaria films on 3 consecutive days or a malaria rapid diagnostic test (antigen detection, p. 355). Subsequent investigations in patients with HIV-related (p. 396), immune-deficient (p. 301), nosocomial or travel-related (p. 309) pyrexia and in individuals with associated symptoms or signs of involvement of the respiratory, gastrointestinal or neurological systems are described elsewhere. In most patients, the site of infection is apparent after clinical evaluation (p. 294), and the likelihood of infection is reinforced by investigation results (e.g. neutrophilia with raised ESR and CRP in bacterial infections). Not all apparently localising symptoms are reliable, however; headache, breathlessness and diarrhoea can occur in sepsis without localised infection in the central nervous system (CNS), respiratory tract or gastrointestinal tract. Careful interpretation of the clinical features is vital (e.g. severe headache associated with photophobia, rash and neck stiffness suggests meningitis, whereas moderate headache with cough and rhinorrhoea is consistent with a viral upper respiratory tract infection). Common infections that present with fever are shown in Figure 13.1. Further investigation and management are specific to the cause, but may include empirical antimicrobial therapy (p. 149) pending confirmation of the microbiological diagnosis. Major causes of PUO are outlined in Box 13.2. Rare causes, such as periodic fever syndromes (p. 85), should be considered in those with a positive family history. Children and younger adults are more likely to have infectious causes – in particular, viral infections. Older adults are more likely to have certain infectious and non-infectious causes (see Box 13.1). Detailed history and examination should be repeated at regular intervals to detect emerging features (e.g. rashes, signs of infective endocarditis (p. 625) or features of vasculitis). In men, the prostate should be considered as a potential source of infection. Clinicians should be alert to the possibility of factitious fever, in which high temperature recordings are engineered by the patient (Box 13.3). If initial investigation of fever (see above) is negative, a series of further microbiological and non-microbiological investigations should be considered (Boxes 13.4 and 13.5). These will usually include: • induced sputum or other specimens for mycobacterial stains and culture • imaging of the abdomen by ultrasonography or computed tomography (CT) Intravenous injection of recreational drugs is widespread in many parts of the world (p. 240). Infective organisms are introduced by non-sterile (often shared) injection equipment (Fig. 13.2), and infection is facilitated by immunodeficiency due to malnutrition or the toxic effects of drugs. The risks increase with prolonged drug use and injection into large veins of the groin and neck because of progressive thrombosis of superficial peripheral veins. The most common causes of fever are soft tissue or respiratory infections. The history should address the following risk factors: • Site of injection. Femoral vein injection is associated with vascular complications such as deep venous thrombosis (50% of which are septic) and accidental arterial injection with false aneurysm formation or a compartment syndrome due to swelling within the fascial sheath. Local complications include ilio-psoas abscess, and septic arthritis of the hip joint or sacroiliac joint. Injection of the jugular vein can be associated with cerebrovascular complications. Subcutaneous and intramuscular injection has been related to infection by clostridial species, the spores of which contaminate heroin. Clostridium novyi causes a local lesion with significant toxin production, leading to shock and multi-organ failure. Tetanus, wound botulism and gas gangrene also occur. • Technical details of injection. Sharing of needles and other injecting paraphernalia (including spoons and filters) greatly increases the risk of blood-borne virus infection (e.g. HIV-1, hepatitis B or C virus). Some users lubricate their needles by licking them prior to injection, thus introducing mouth organisms (e.g. anaerobic streptococci, Fusobacterium spp. and Prevotella spp). Contamination of commercially available lemon juice, used to dissolve heroin before injection, has been associated with blood-stream infection with Candida spp. • Substances injected. Injection of cocaine is associated with a variety of vascular complications. Certain formulations of heroin have been linked with particular infections, e.g. wound botulism with black tar heroin. Drugs are often mixed with other substances, e.g. talc. • Blood-borne virus status. Results of previous HIV-1 and hepatitis virus tests or vaccinations for hepatitis viruses should be recorded. • Surreptitious use of antimicrobials. Addicts may use antimicrobials to self-treat infections, masking initial blood culture results. Key findings on clinical examination are shown in Figure 13.2. It can be difficult to distinguish the effects of infection from the effects of drugs or drug withdrawal (excitement, tachycardia, sweating, marked myalgia, confusion). Stupor and delirium may result from drug administration but may also indicate meningitis or encephalitis. Non-infected venous thromboembolism is also common in this group. The initial investigations are as for any fever (see above), including a chest X-ray and blood cultures. Since blood sampling may be difficult, contamination is often a problem. Echocardiography to detect infective endocarditis should be performed in all injection drug-users with: bacteraemia due to Staphylococcus aureus or other organisms associated with endocarditis (Fig. 13.3A); thromboembolic phenomena; or a new or previously undocumented murmur. Endovascular infection should also be suspected if lung abscesses or pneumatocoeles are detected radiologically. Additional imaging should be focused on sites of injection or of localising symptoms and signs (Fig. 13.3B). Any pathological fluid collections should be sampled. Microbiological results are crucial in guiding therapy. Injection drug-users may have more than one infection. Skin and soft tissue infections are most often due to Staph. aureus or streptococci, and sometimes to Clostridium spp. or anaerobes. Pulmonary infections are most often due to the common pathogens causing community-acquired pneumonia, tuberculosis or septic emboli (Fig. 13.3C). Endocarditis with septic emboli commonly involves Staph. aureus and viridans streptococci, but Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Candida spp. are also encountered. Immunocompromised hosts include those with congenital immunodeficiency (p. 78), HIV infection (Ch. 14) and iatrogenic immunosuppression induced by chemotherapy (p. 276), transplantation (p. 95) or immunosuppressant medicines, including high-dose corticosteroids. Metabolic abnormalities, such as under-nutrition or hyperglycaemia, may also contribute. Multiple elements of the immune system are potentially compromised. A patient may have impaired neutrophil function from chemotherapy, impaired T-cell and/or B-cell responses due to underlying malignancy, T-cell and phagocytosis defects due to corticosteroids, mucositis from chemotherapy and an impaired skin barrier due to insertion of a central venous catheter. Fever may result from infectious or from non-infectious causes, including drugs, vasculitis, neoplasm, organising pneumonitis, lymphoproliferative disease, graft-versus-host disease (in recipients of haematopoietic stem cell transplants; p. 1017) or Sweet’s syndrome (reddish nodules or plaques with fever and leucocytosis, in association with haematological malignancy). The following should be addressed in the history: • Identification of the immunosuppressant factors, and nature of the immune defect. • Any past infections and their treatment. Infections may recur and antimicrobial resistance may have been acquired in response to prior therapy. • Exposure to infections, including opportunistic infections that would not cause disease in an immunocompetent host. Initial screening tests are as described above (p. 296). Immunocompromised hosts often have decreased inflammatory responses leading to attenuation of physical signs, such as neck stiffness with meningitis, radiological features and laboratory findings, such as leucocytosis. Chest CT scan should be considered in addition to chest X-ray when respiratory symptoms occur. Abdominal imaging may also be warranted, particularly if there is right lower quadrant pain, which may indicate typhlitis (inflammation of the caecum) in neutropenic patients. Blood cultures from a central venous catheter, urine cultures, and stool cultures if diarrhoea is present are also recommended. Neutropenic fever is strictly defined as a neutrophil count of less than 0.5 × 109/L (p. 1004) and a single axillary temperature above 38.5°C or three recordings above 38.0°C over a 12-hour period, although the infection risk increases progressively as the neutrophil count drops below 1.0 × 109/L. Patients with neutropenia are particularly prone to bacterial or fungal infection. Gram-positive organisms are the most common pathogens, particularly in association with in-dwelling catheters. Empirical broad-spectrum antimicrobial therapy is commenced as soon as neutropenic fever occurs and cultures have been obtained. The most common regimens for neutropenic sepsis are broad-spectrum penicillins, such as piperacillin–tazobactam IV. Although aminoglycosides are commonly used in combination, routine use is not supported by trial data (Box 13.6). If fever has not resolved after 3–5 days, empirical antifungal therapy (e.g. caspofungin) is added (p. 159). An alternative antifungal strategy is to use azole prophylaxis in high-risk patients and markers of early fungal infection, such as galactomannan antigen, to guide initiation of antifungal treatment (a ‘pre-emptive approach’). Fever in transplant recipients may be due to infection, episodes of graft rejection in solid organ transplant recipients, or graft-versus-host disease following haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT; p. 1017). Infections in solid transplant recipients are grouped according to the time of onset (Box 13.7). Those in the first month are related to the underlying condition or surgical complications. Those occurring 1–6 months after transplantation are characteristic of impaired T-cell function. Risk factors for CMV infection have been identified and patients commonly receive either prophylaxis or intensive monitoring involving regular testing for CMV DNA by PCR and early initiation of anti-CMV therapy using intravenous ganciclovir or oral valganciclovir if tests become positive.

Infectious disease

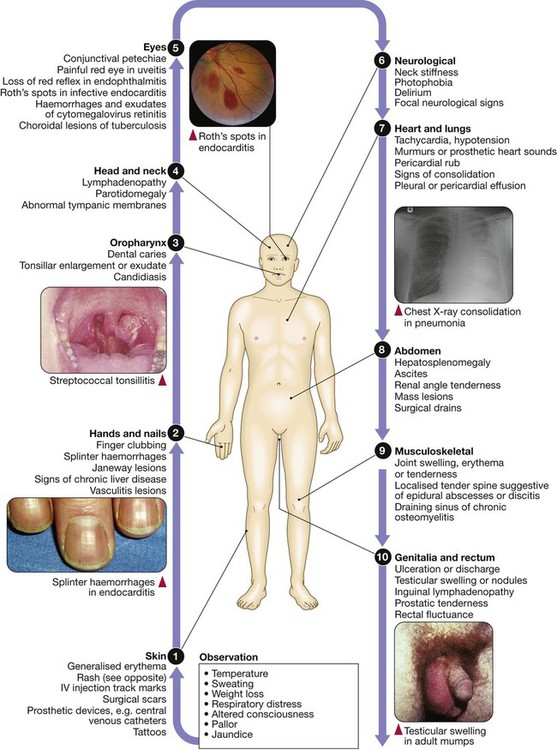

Clinical examination of patients with infectious disease

Fever

Presenting problems in infectious diseases

Fever

Investigations

Fever with localising symptoms or signs

Major causes are grouped by approximate anatomical location and include central nervous system infection; respiratory tract infections; abdominal, pelvic or urinary tract infections; and skin and soft tissue infections (SSTI) or osteomyelitis. For each site of infection, particular syndromes and their common causes are described elsewhere in the book. The causative organisms vary, depending on host factors, which include whether the patient has lived or resided in a tropical country or particular geographical location, has acquired the infection in a health-care environment or is immunocompromised.

Pyrexia of unknown origin

Clinical assessment

Investigations

Fever in the injection drug-user

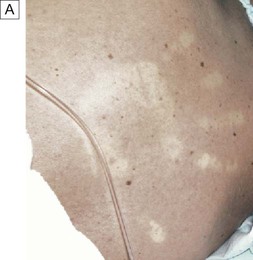

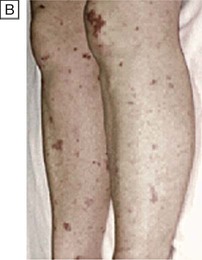

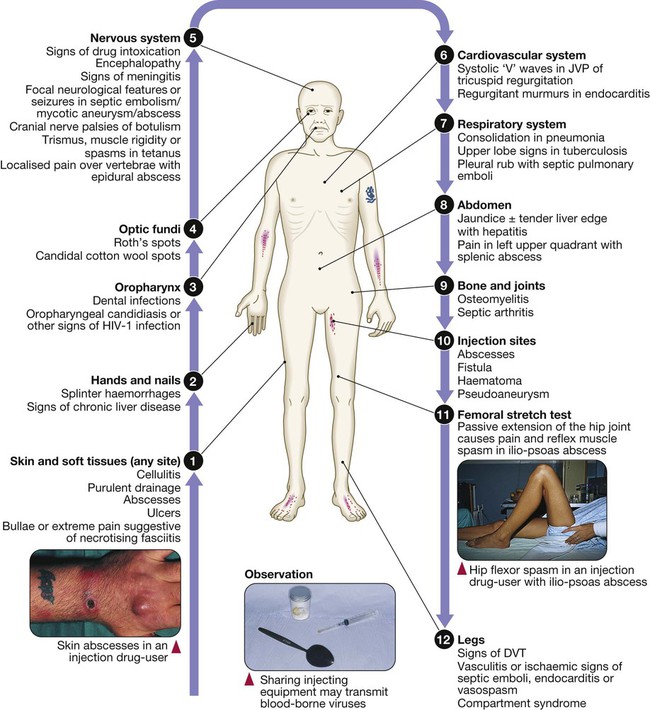

Full examination (p. 294) is required but features most common amongst injection drug-users are shown here. (DVT = deep venous thrombosis; JVP = jugular venous pulse)

Clinical assessment

Investigations

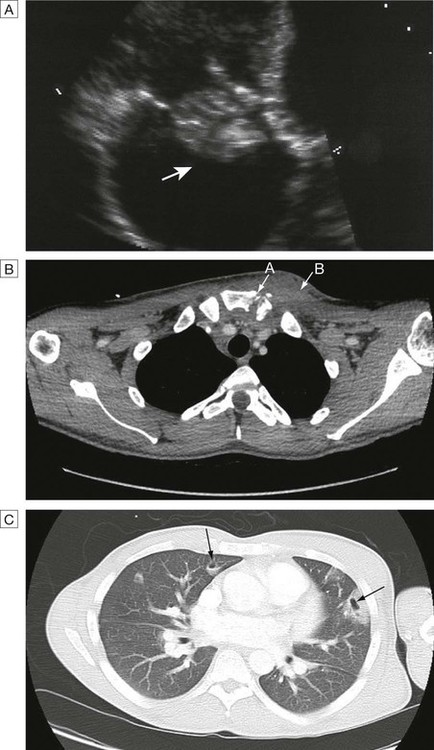

A Endocarditis: large vegetation on the tricuspid valve (arrow). B Septic arthritis of the left sternoclavicular joint (arrow A) (note the erosion of the bony surfaces at the sternoclavicular joint) with overlying soft tissue collection (arrow B). C CT of the thorax showing Staph. aureus endocarditis of the tricuspid valve and haemoptysis, showing multiple embolic lesions with cavitatlon (arrows).

Fever in the immunocompromised host

Clinical assessment

Investigations

Neutropenic fever

Post-transplantation fever