The environment contains thousands of pathogenic microorganisms. Normally, our host defense system protects us from these harmful invaders. When this network of safeguards breaks down, however, the result is an altered immune response or immune system failure. Disorders of the immune system discussed in this chapter include acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, allergic rhinitis, anaphylaxis, atopic dermatitis, latex allergy, lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, urticaria and angioedema, and vasculitis.

ACQUIRED IMMUNODEFICIENCY SYNDROME

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection may cause acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). Although it’s characterized by gradual destruction of cell-mediated (T cell) immunity, it also affects humoral immunity and even autoimmunity because of the central role of the CD4+ (helper) T lymphocyte in immune reactions. The resulting immunodeficiency makes the patient susceptible to opportunistic infections, cancers, and other abnormalities that characterize AIDS. (See Common infections and neoplasms in HIV and AIDS.)

AIDS was first described by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in 1981. Because transmission is similar, AIDS shares epidemiologic patterns with hepatitis B and sexually transmitted diseases.

The CDC estimates that more than 1 million people in the United States are infected with

HIV, one-quarter of whom are unaware of their infection. The AIDS epidemic is growing most rapidly among homosexual and bisexual men of all races, Blacks, and Hispanic groups in the United States. It’s the leading killer of Black men ages 25 to 44, and it affects nearly seven times more Blacks and three times more Hispanics than Whites.

Depending on individual variations and the presence of cofactors that influence disease progression, the time from acute HIV infection to the appearance of symptoms (mild to severe) to the diagnosis of AIDS and, eventually, to death varies greatly. Combination drug therapy in conjunction with treatment and prophylaxis of common opportunistic infections can delay the natural progression and prolong survival.

Causes

The HIV-1 retrovirus is the primary cause. Transmission occurs by contact with infected blood or body fluids and is associated with identifiable high-risk behaviors. It’s disproportionately represented in:

♦ homosexual and bisexual men

♦ I.V. drug users

♦ recipients of contaminated blood or blood products (dramatically decreased since mid-1985)

♦ heterosexual partners of persons in the former groups

♦ neonates of infected women.

Pathophysiology

The natural history of AIDS begins with infection by the HIV retrovirus, which is detectable only by laboratory tests, and ends with death. Twenty years of data strongly suggests that HIV isn’t transmitted by casual household or social contact. The HIV virus may enter the body by any of several routes involving the transmission of blood or body fluids, for example:

♦ direct inoculation during intimate sexual contact, especially associated with the mucosal trauma of receptive rectal intercourse

♦ transfusion of blood or clotting factors used from 1978 to 1985

♦ sharing of contaminated needles

♦ transplacental or postpartum transmission from infected mother to fetus (by cervical or blood contact at delivery and in breast milk).

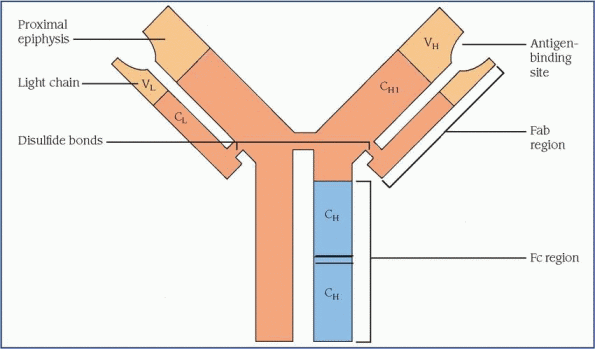

HIV strikes helper T cells bearing the CD4+ antigen. Normally a receptor for major histocompatibility complex molecules, the antigen serves as a receptor for the retrovirus and allows it to enter the cell. Viral binding also requires the presence of a coreceptor (believed to be the chemokine receptor CCR5) on the cell surface. The virus also may infect CD4+ antigen-bearing cells of the GI tract, uterine cervix, and neuroglia.

Like other retroviruses, HIV copies its genetic material in a reverse manner compared with other viruses and cells. Through the action of reverse transcriptase, HIV produces DNA from its viral RNA. Transcription is typically poor, leading to mutations, some of which make HIV resistant to antivirals. The viral DNA enters the nucleus of the cell and is incorporated into the host cell’s DNA, where it’s transcribed into more viral RNA. If the host cell reproduces, it duplicates the HIV DNA along with its own and passes it on to the daughter cells. Thus, if activated, the host cell carries this information and, if activated, replicates the virus. Viral enzymes, proteases, arrange the structural components and RNA into viral particles that move out to the periphery of the host cell, where the virus buds and emerges from the host cell. Thus, the virus is now free to travel and infect other cells.

HIV replication may lead to cell death or it may become latent. HIV infection leads to profound pathology, either directly through destruction of CD4+ cells, other immune cells, and neuroglial cells, or indirectly through the secondary effects of CD4+ T-cell dysfunction and resulting immunosuppression.

The HIV infectious process takes three forms:

♦ immunodeficiency (opportunistic infections and unusual cancers)

♦ autoimmunity (lymphoid interstitial pneumonitis, arthritis, hypergammaglobulinemia, and production of autoimmune antibodies)

♦ neurologic dysfunction (AIDS dementia complex, HIV encephalopathy, and peripheral neuropathies).

Signs and symptoms

HIV infection manifests in many ways. After a high-risk exposure and inoculation, the infected person usually experiences a mononucleosislike syndrome, which may be attributed to flu or another virus and then may remain asymptomatic for years. In this latent stage, the only sign of HIV infection is laboratory evidence of seroconversion.

When signs and symptoms appear, they may take many forms, including:

♦ persistent generalized lymphadenopathy secondary to impaired function of CD4+ cells

♦ nonspecific signs and symptoms, including rapid weight loss; profound, unexplained fatigue; night sweats; fevers related to altered function of CD4+ cells; immunodeficiency; infection of other CD4+ antigen-bearing cells; persistent yeast infections (oral or vaginal); dry cough;

diarrhea lasting more than a week; and pneumonia

♦ neurologic symptoms resulting from HIV encephalopathy and infection of neuroglial cells, including memory loss and depression

♦ opportunistic infection or cancer related to immunodeficiency.

In children, HIV infection has a mean incubation time of 17 months. Signs and symptoms resemble those in adults, except for findings related to sexually transmitted diseases. Children have a high incidence of opportunistic bacterial infections: otitis media, sepsis, chronic salivary gland enlargement, lymphoid interstitial pneumonia,

In children, HIV infection has a mean incubation time of 17 months. Signs and symptoms resemble those in adults, except for findings related to sexually transmitted diseases. Children have a high incidence of opportunistic bacterial infections: otitis media, sepsis, chronic salivary gland enlargement, lymphoid interstitial pneumonia, Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare

complex function, and pneumonias, including Pneumocystis carinii.

Complications

♦ Opportunistic infections

♦ Certain cancers

Diagnosis

Signs and symptoms may occur at any time after infection with HIV, but AIDS is not officially diagnosed until the patient’s CD4+ T cell count is less than 200 cells/µl. AIDS is the final stage of HIV infection, and it may take years for HIV infection to reach this stage, even without treatment.

The CDC recommends testing for HIV 1 month after a possible exposure—the approximate length of time before antibodies can be detected in the blood. However, because people produce detectable levels of antibodies at different rates, the time can vary from a few weeks to as long as 35 months, so an HIV-infected person can test negative for HIV antibodies. Antibody tests in neonates may also be unreliable because transferred maternal antibodies persist for up to 10 months, causing a false-positive result. Standard HIV testing typically consists of the enzyme-linked immunoassay. If the results are positive, the test should be repeated, then confirmed by the Western blot or immunofluorescence assay.

Other blood tests support the diagnosis and are used to evaluate the severity of immunosuppression. They include CD4+ and CD8+ cell (killer T cell) subset counts, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), complete blood count, serum beta (sub 2) microglobulin, p24 antigen, neopterin levels, and anergy testing.

Many opportunistic infections in AIDS patients are reactivations of previous infections. Therefore, patients may also be tested for syphilis, hepatitis B, tuberculosis, toxoplasmosis, and histoplasmosis.

Treatment

Although no cure for AIDS exists, antiretrovirals are used to control the reproduction of HIV and slow the progression of HIV-related disease. Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy, commonly referred to as HAART, is the recommended treatment for HIV infection. HAART combines three or more antiretrovirals in a daily regimen:

♦ nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors to bind to and disable reverse transcriptase proteins

♦ nucleoside analogues or reverse transcriptase inhibitors to halt reproduction of the virus by interfering with viral reverse transcriptase, which impairs HIV’s ability to turn its RNA into DNA for insertion into the host cell

♦ protease inhibitors to disable protease, a protein that HIV needs to replicate virons, the viral particles that spread the virus to other cells.

Additional treatment

♦ An immunomodulator to boost the immune system weakened by AIDS and retroviral therapy

♦ Human granulocyte colony-stimulating growth factor to stimulate neutrophil production (retroviral therapy causes anemia, so patients may receive epoetin alfa)

♦ An anti-infective and an antineoplastic to combat opportunistic infections and associated cancers (some prophylactically to help resist opportunistic infections)

♦ Supportive therapy, including nutritional support, fluid and electrolyte replacement therapy, pain relief, and psychological support

Special considerations

♦ Advise health care workers and the public to use precautions in all situations that risk exposure to blood, body fluids, and secretions. Diligent practice of standard precautions can prevent the inadvertent transmission of AIDS and other infectious diseases transmitted by similar routes.

♦ Recognize that a diagnosis of AIDS is profoundly distressing because of the disease’s social impact and discouraging prognosis. The patient may lose his job and financial security as well as the support of family and friends. Do your best to help the patient cope with an altered body image, the emotional burden of serious illness, and the threat of death. Encourage and assist the patient in learning about AIDS societies and support programs. (See

Preventing AIDS transmission,

page 442.)

The immune system’s ability to fight off infections and other immune system disorders decreases with age.

The immune system’s ability to fight off infections and other immune system disorders decreases with age. At age 2, a child’s immune system is fully functioning. Infants between ages 6 and 9 months are particularly vulnerable to disease because they’re no longer supported by maternal antibodies and their own immune system isn’t yet established.

At age 2, a child’s immune system is fully functioning. Infants between ages 6 and 9 months are particularly vulnerable to disease because they’re no longer supported by maternal antibodies and their own immune system isn’t yet established.

In children, HIV infection has a mean incubation time of 17 months. Signs and symptoms resemble those in adults, except for findings related to sexually transmitted diseases. Children have a high incidence of opportunistic bacterial infections: otitis media, sepsis, chronic salivary gland enlargement, lymphoid interstitial pneumonia, Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex function, and pneumonias, including Pneumocystis carinii.

In children, HIV infection has a mean incubation time of 17 months. Signs and symptoms resemble those in adults, except for findings related to sexually transmitted diseases. Children have a high incidence of opportunistic bacterial infections: otitis media, sepsis, chronic salivary gland enlargement, lymphoid interstitial pneumonia, Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex function, and pneumonias, including Pneumocystis carinii.