Patient Story

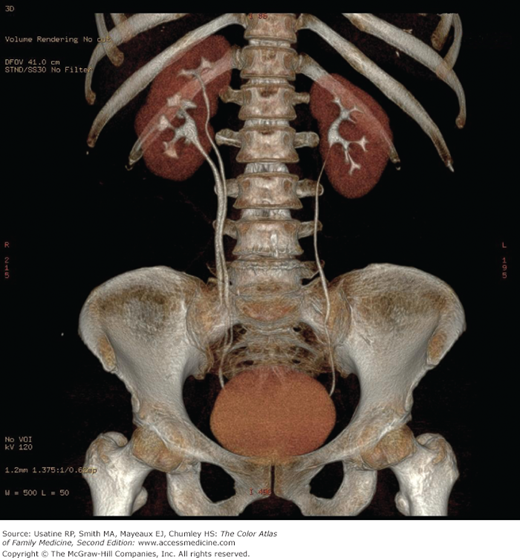

A 74-year-old man presented with a 2-day history of severe, steady pain radiating down to the lower abdomen and left testicle. He has had urinary frequency, nocturia, hesitancy, and urinary dribbling for several years with slight worsening with time. CT scan revealed left-sided hydronephrosis (Figure 69-1). In this patient, an irregular mass was seen at the left ureterovesical junction compressing the bladder. Prostate cancer was found on biopsy.

Introduction

Hydronephrosis refers to distention of the renal calyces and pelvis of one or both kidneys by urine. Hydronephrosis is not a disease but a physical result of urinary blockage that may occur at the level of the kidney, ureters, bladder, or urethra. The condition may be physiologic (e.g., occurring in up to 80% of pregnant women) or pathologic.

Epidemiology

- The most common cause of congenital bilateral hydronephrosis is posterior urethral valves (in males). Other causes include narrowing of the ureteropelvic or ureterovesicular junction.

- Using a large European database for surveillance of congenital malformations (EUROCAT), authors found a prevalence of congenital hydronephrosis of 11.5 cases per 10,000 births; the majority (72%) was in males.1

- Ureteropelvic junction obstruction is one of the most common congenital abnormalities of the urinary tract causing hydronephrosis, occurring in approximately 1 in 5000 to 8000 live births.2

- Authors of one systematic review reported a mean prevalence of 15% for postnatal primary vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) in children after prenatally detected hydronephrosis.3 Of the remaining cases, 53% had no postnatal anomalies and 29% had other anomalies (e.g., duplicate collecting systems; Figure 69-2).

- Among acquired causes in adults, pelvic tumors, renal calculi, and urethral stricture predominate.4 If renal colic is present, renal stone is likely present (90% in one study).5

- Hydronephrosis is common in pregnancy because of the compression from the enlarging uterus and functional effects of progesterone.

Etiology and Pathophysiology

- Bilateral hydronephrosis is caused by a blockage to urine flow occurring at or below the level of the bladder or urethra.

- Unilateral hydronephrosis is caused by a blockage to urine flow occurring above the level of the bladder.

- Multiple causes result in this condition including congenital (e.g., VUR), acquired intrinsic (e.g., calculi, inflammation, and trauma), and acquired extrinsic (e.g., pregnancy or uterine leiomyoma, retroperitoneal fibrosis). Within these groupings, obstruction may be a result of mechanical (e.g., benign prostatic hypertrophy) or functional (e.g., neurogenic bladder) defects.

- Urinary obstruction causes a rise in ureteral pressure leading to declines in glomerular filtration, tubular function (e.g., ability to transport sodium and potassium or adjust urine concentration), and renal blood flow.

- If obstruction persists, tubular atrophy and permanent nephron loss can occur.

Diagnosis

- In children, the diagnosis of hydronephrosis or megaureter is often made by a routine ultrasound.

- A work-up for hydronephrosis in adults is often triggered by the discovery of azotemia (caused by impaired excretory function of sodium, urea, and water). Sudden or new onset of hypertension (because of the increased renin release with unilateral obstruction) may also trigger an investigation. A first step in the evaluation is to perform bladder catheterization. If diuresis occurs, the obstruction is below the bladder neck.

- Pain is the symptom that most commonly leads an adult patient to seek medical attention. This is caused by distention of the collecting system or renal capsule. The pain is often described as severe, steady, and radiating down to the lower abdomen, testicles, or labia. Flank pain with urination is pathognomonic for VUR.

- Disturbed excretory function or difficulty in voiding: Oliguria and anuria are symptoms of complete obstruction whereas polyuria and nocturia occur with partial obstruction (impaired concentrating ability causes osmotic diuresis).

- Fever or dysuria can occur with associated urinary tract infection (UTI).

- The physical examination may reveal distention of the kidney or bladder. Rectal exam may show an enlarged prostate or rectal/pelvic mass and pelvic examination may reveal an enlarged uterus or pelvic mass.

- Urinalysis may show hematuria, pyuria, proteinuria, or bacteruria but the sediment is often normal.3

- Assess renal function (blood urea nitrogen [BUN], creatinine).

- Urodynamic testing may be indicated for patients with neurogenic bladder or other suspected bladder causes of hydronephrosis.

- Ultrasound imaging has a sensitivity and specificity of 90% for identifying the presence of hydronephrosis if no diuresis occurs following bladder catheterization.4

- If a source remains unidentified, an IV urogram (Figures 69-1 and 69-3) and/or CT scan (Figure 69-4) should be obtained to diagnose intraabdominal or retroperitoneal causes.

- One study of magnetic resonance (MR) pyelography (vs. ultrasound and urography) reported a sensitivity in detecting stones, strictures, and congenital ureteropelvic junction obstructions of 68.9%, 98.5%, and 100%, respectively, with a specificity of 98%.6 Accuracy regarding the level of obstruction was high (100%).

- Antegrade urography (percutaneous placement of ureteral catheter) or retrograde urography (cystoscopic placement of ureteral catheter) may be needed in patients with azotemia and poor excretory function or in those at high risk of acute renal failure from IV contrast (i.e., diabetes, multiple myeloma).

- A voiding cystourethrogram is useful in the diagnosis of VUR and bladder neck and urethral obstructions.

- For children identified in the prenatal period with hydronephrosis, the American Urologic Association (AUA) recommends a voiding cystourethrogram if there is high-grade hydronephrosis, hydroureter, or an abnormal bladder on ultrasound (late-term prenatal or postnatal), or for children who develop a UTI on observation.7 SOR C Given the unproven value in diagnosing and treating VUR, an observational approach without screening may be taken for children with lesser grades of prenatally detected hydronephrosis (Society for Fetal Urology [SFU] grade 1 or 2).

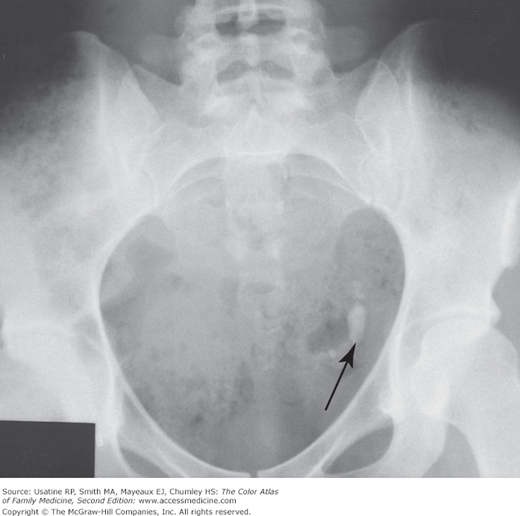

Figure 69-3

Large irregular calcification (arrow) representing ureterolithiasis in the left side of the pelvis in the patient in Figure 69-1. (From Schwartz DT, Reisdorff EJ. Emergency Radiology. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2000:539, Fig. 19-43. Copyright 2000.)