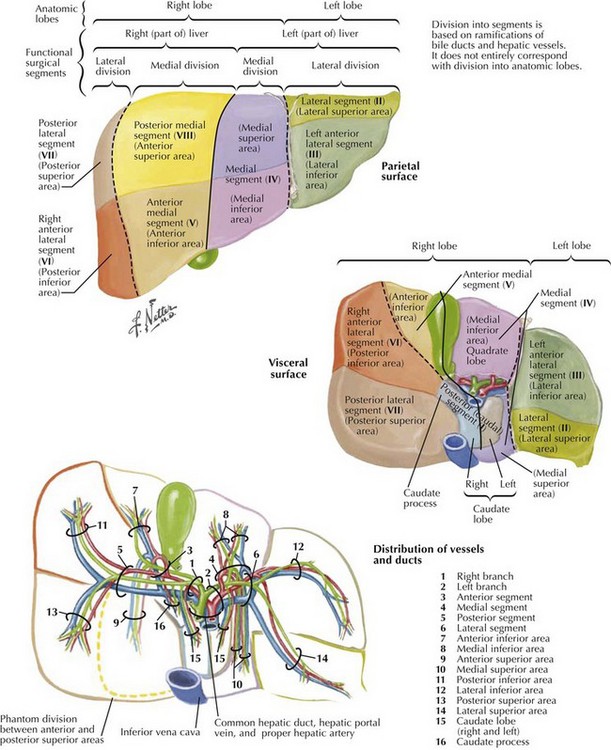

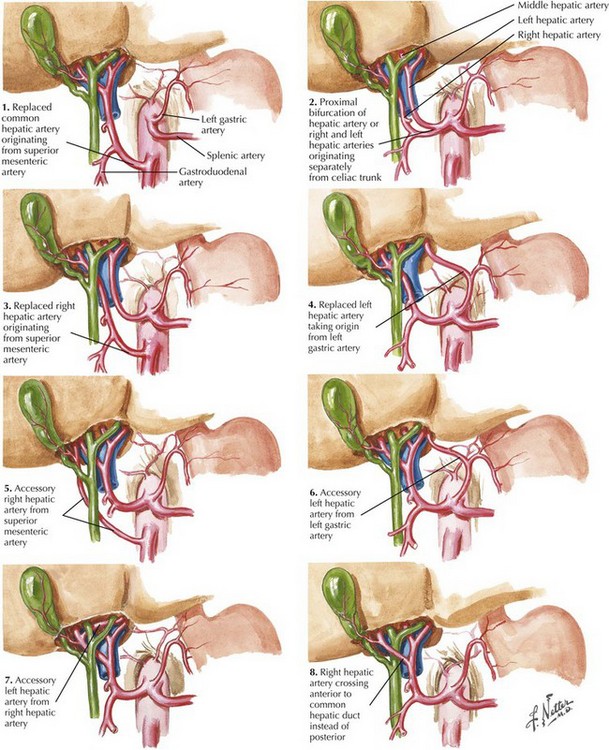

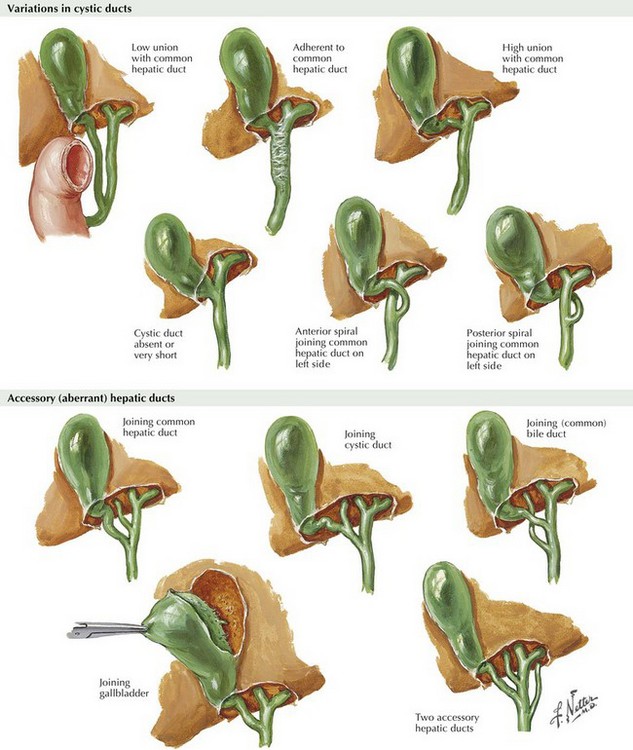

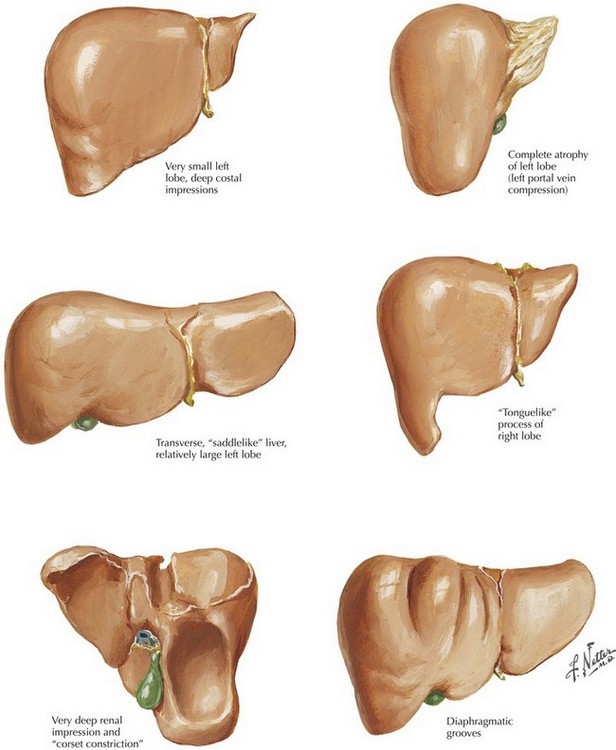

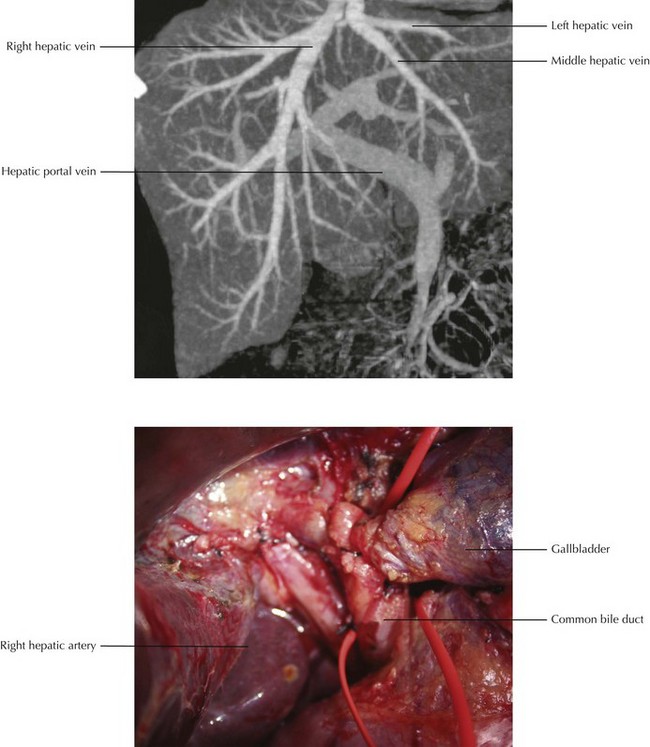

Chapter 14 The liver is composed of eight segments based on the portal inflow into the organ (Fig. 14-1). Segments I to IV constitute the left lobe (colored purple, blue, and green on illustration) and segments V to VIII, the right lobe. Preoperative understanding of the patient’s underlying liver anatomy is critical when planning a liver resection. Because of the wide variability in all the hepatic vascular and biliary structures, as well as a considerable amount of variability in the relative sizes of the right and left lobes, imaging is performed to delineate the key structures that may be encountered during the resection (Fig. 14-2). The most useful studies are triple-phase computed tomography or a high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging with contrast (Fig. 14-3). FIGURE 14–3 Hepatic artery: magnetic resonance image and surgical view. Arterial supply to the liver is through the hepatic artery, which supplies branches to the right and left lobes. Variations in the arterial supply to the liver include an additional, accessory, or replaced right or left hepatic artery and an aberrant origin of the common hepatic artery (Fig. 14-4). The most common variants of the arterial blood supply to the liver include an additional or replaced right hepatic artery from the superior mesenteric artery. This vessel is usually one of the first branches off the superior mesenteric and courses behind the head of the pancreas, posterior to the portal vein and common bile duct, traveling directly into the right lobe of the liver. Considerable variations exist in the relative size of the right and left lobes of the liver (Fig. 14-5). In addition to the size of each lobe, the underlying health of the liver parenchyma must also be factored into the decision regarding the minimum amount of liver that must remain for the patient to avoid liver insufficiency. Patients with cirrhosis or hepatic steatosis may need larger residual volumes after resection to maintain adequate function (Fig. 14-6).

Hepatectomy

Surgical Principles

(CT image from Kamel IR, Liapi E, Fishman E. Liver and biliary system: evaluation by multidetector CT. Radiol Clin North Am 2005;43(6):977-97.)

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Basicmedical Key

Fastest Basicmedical Insight Engine