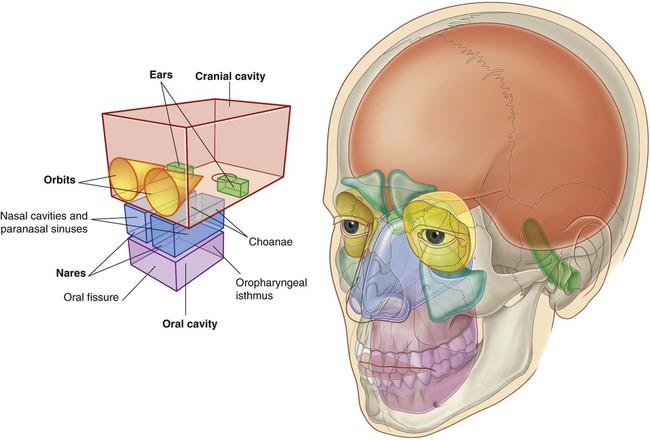

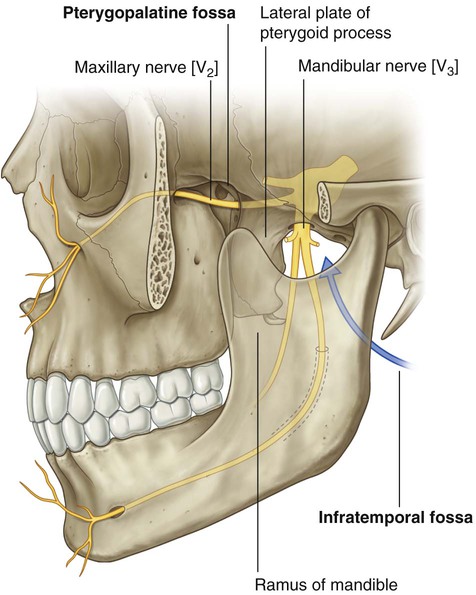

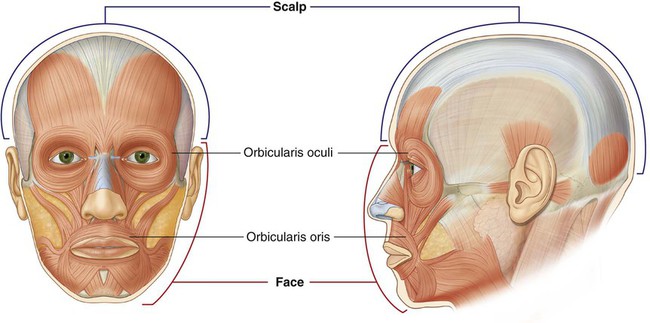

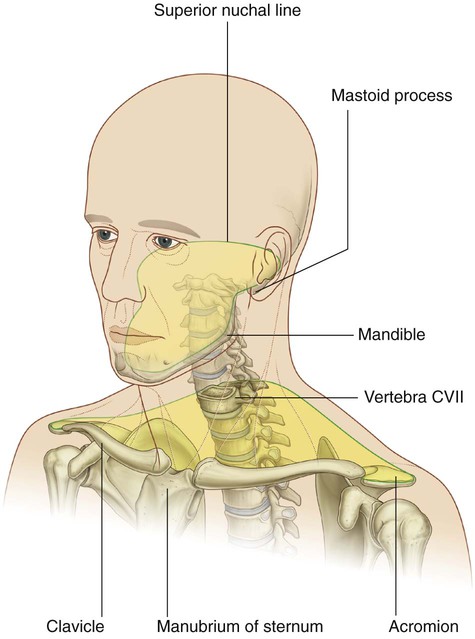

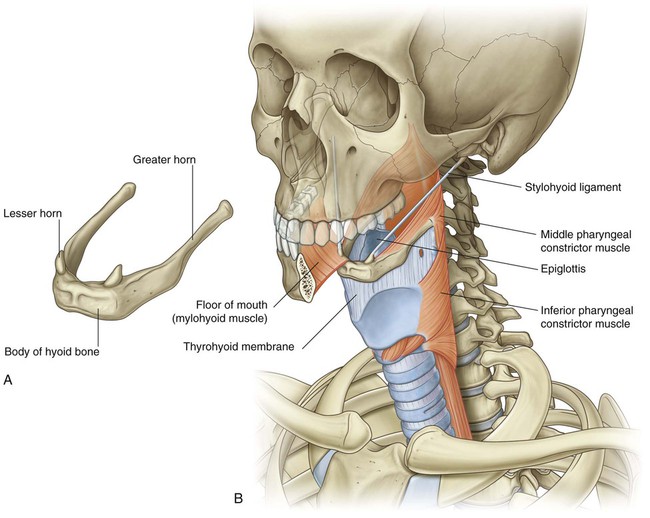

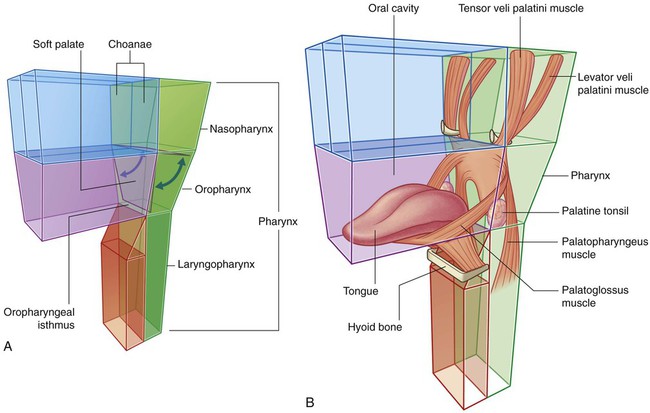

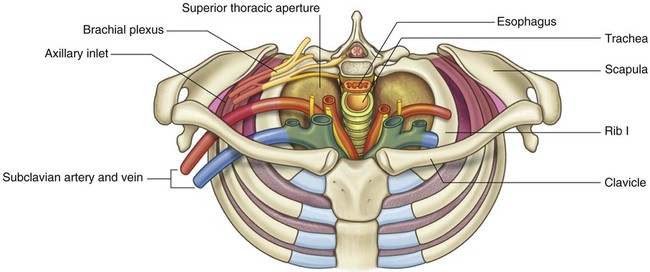

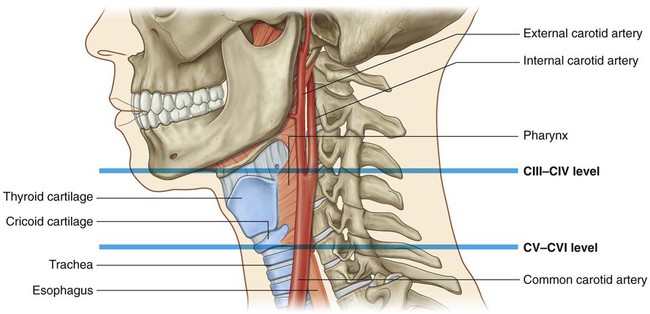

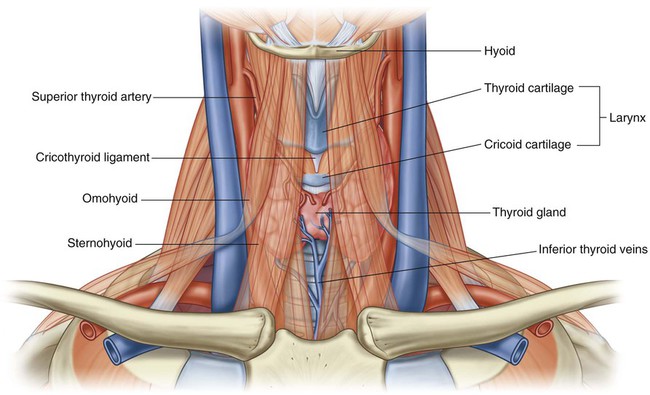

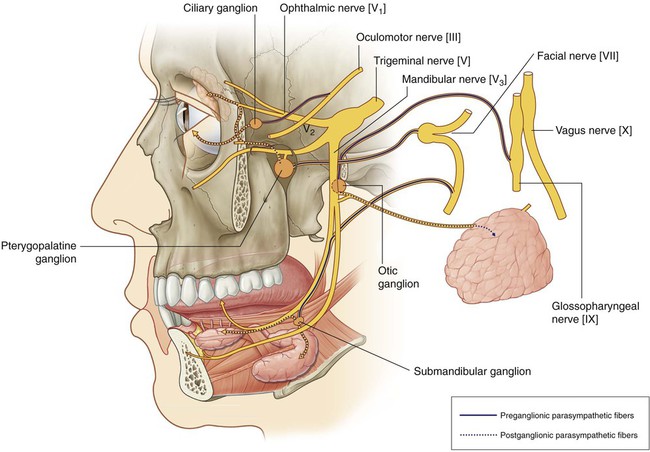

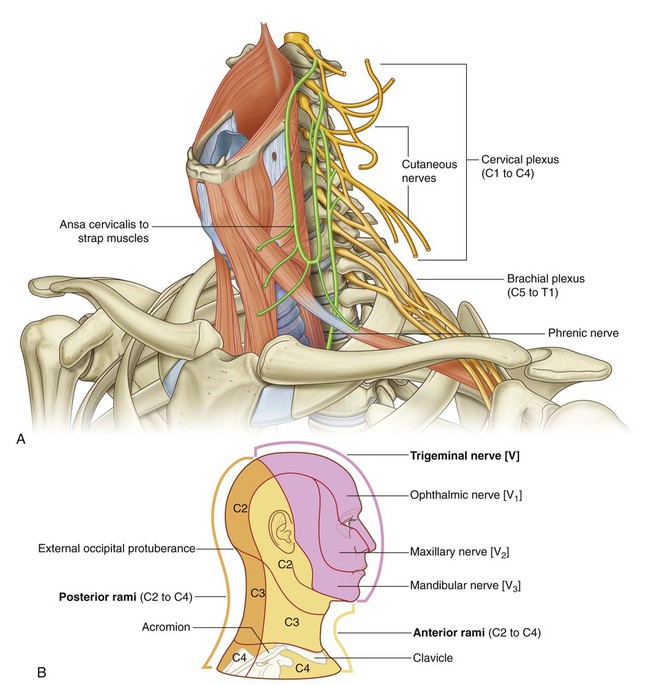

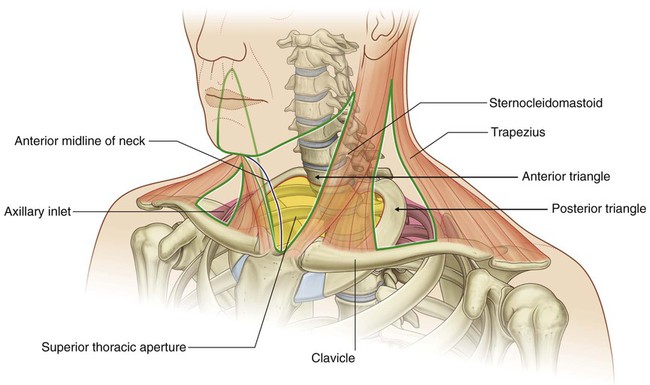

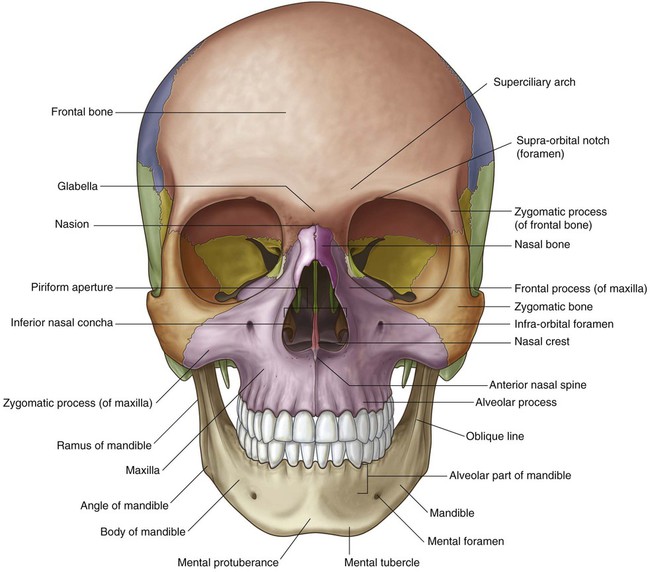

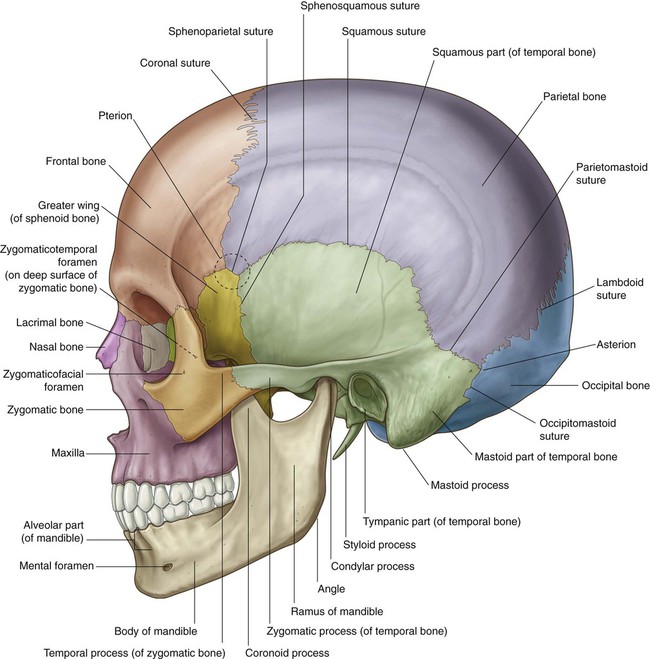

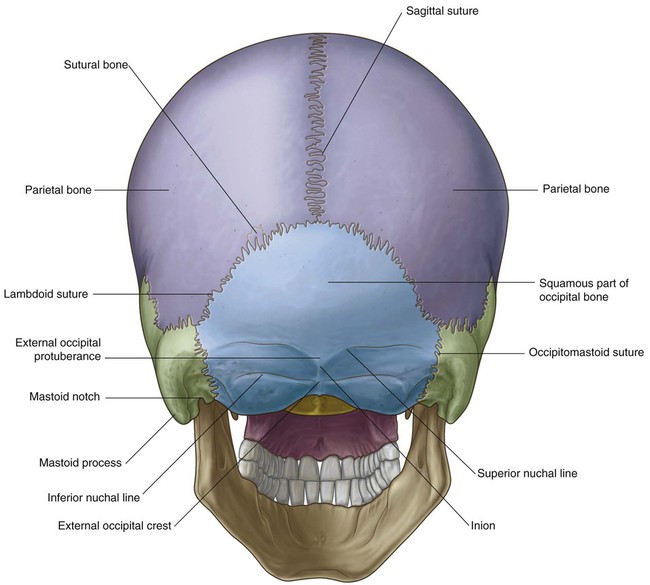

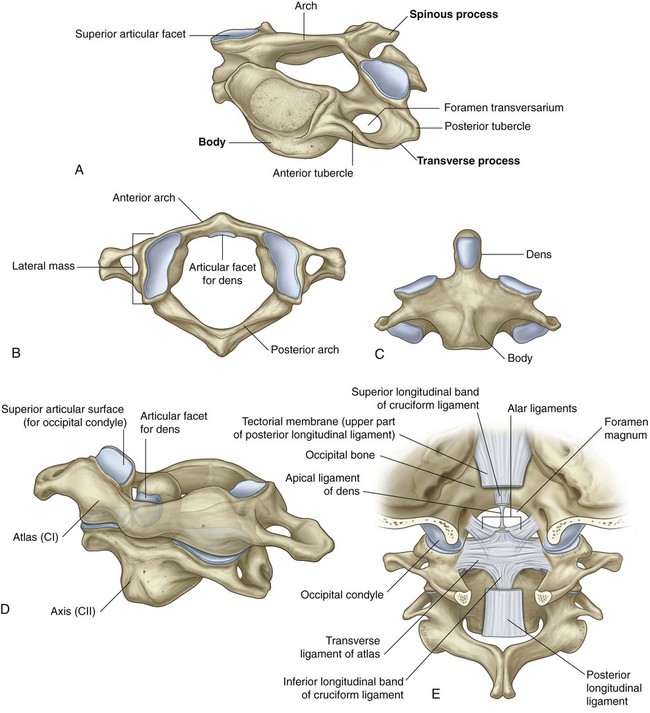

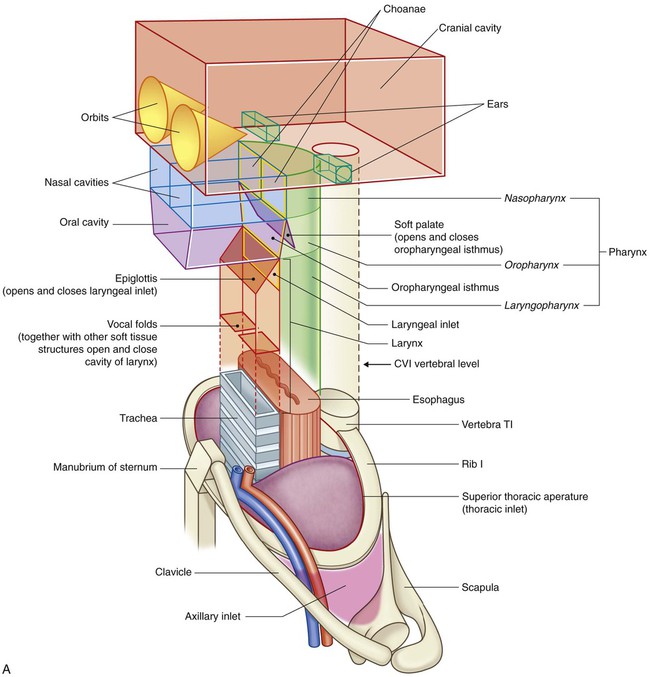

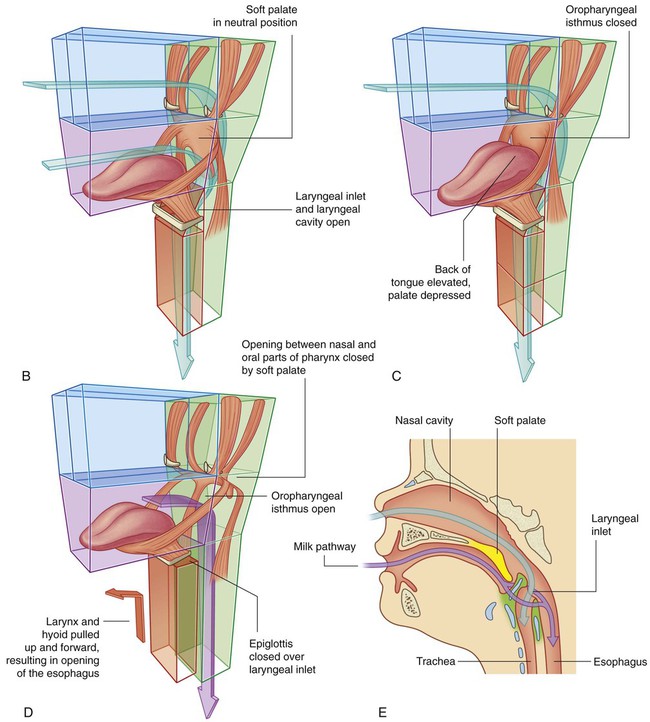

8 ADDITIONAL LEARNING RESOURCES for Chapter 8, Head and Neck, on STUDENT CONSULT (www.studentconsult.com): The head and neck are anatomically complex areas of the body. In addition to the major compartments of the head, two other anatomically defined regions (infratemporal fossa and pterygopalatine fossa) of the head on each side are areas of transition from one compartment of the head to another (Fig. 8.2). The face and scalp also are anatomically defined areas of the head and are related to external surfaces. The face is the anterior aspect of the head and contains a unique group of muscles that move the skin relative to underlying bone and control the anterior openings to the orbits and oral cavity (Fig. 8.3). The scalp covers the superior, posterior, and lateral regions of the head (Fig. 8.3). The neck extends from the head above to the shoulders and thorax below (Fig. 8.4). Its superior boundary is along the inferior margins of the mandible and bone features on the posterior aspect of the skull. The posterior neck is higher than the anterior neck to connect cervical viscera with the posterior openings of the nasal and oral cavities. The neck has four major compartments (Fig. 8.5), which are enclosed by an outer musculofascial collar: The larynx (Fig. 8.6) is the upper part of the lower airway and is attached below to the top of the trachea and above, by a flexible membrane, to the hyoid bone, which in turn is attached to the floor of the oral cavity. A number of cartilages form a supportive framework for the larynx, which has a hollow central channel. The dimensions of this central channel can be adjusted by soft tissue structures associated with the laryngeal wall. The most important of these are two lateral vocal folds, which project toward each other from adjacent sides of the laryngeal cavity. The upper opening of the larynx (laryngeal inlet) is tilted posteriorly, and is continuous with the pharynx. The pharynx (Fig. 8.6) is a chamber in the shape of a half-cylinder with walls formed by muscles and fascia. Above, the walls are attached to the base of the skull, and below to the margins of the esophagus. On each side, the walls are attached to the lateral margins of the nasal cavities, the oral cavity, and the larynx. The two nasal cavities, the oral cavity, and the larynx therefore open into the anterior aspect of the pharynx, and the esophagus opens inferiorly. The many bones of the head collectively form the skull (Fig. 8.7A). Most of these bones are interconnected by sutures, which are immovable fibrous joints (Fig. 8.7B). In the fetus and newborn, large membranous and unossified gaps (fontanelles) between the bones of the skull, particularly between the large flat bones that cover the top of the cranial cavity (Fig. 8.7C), allow: The seven cervical vertebrae form the bony framework of the neck. Cervical vertebrae (Fig. 8.8A) are characterized by: The upper two cervical vertebrae (CI and CII) are modified for moving the head (Fig. 8.8B–E; see also Chapter 2). The hyoid bone is a small U-shaped bone (Fig. 8.9A) oriented in the horizontal plane just superior to the larynx, where it can be palpated and moved from side to side. The hyoid bone does not articulate directly with any other skeletal elements in the head and neck. The muscle groups in the head include: In the neck, major muscle groups include: The superior thoracic aperture (thoracic inlet) opens directly into the base of the neck (Fig. 8.11). Structures passing between the head and thorax pass up and down through the superior thoracic aperture and the visceral compartment of the neck. At the base of the neck, the trachea is immediately anterior to the esophagus, which is directly anterior to the vertebral column. There are major veins, arteries, and nerves anterior and lateral to the trachea. In the neck, the two important vertebral levels (Fig. 8.12) are: The internal carotid artery has no branches in the neck and ascends into the skull to supply much of the brain. It also supplies the eye and orbit. Other regions of the head and neck are supplied by branches of the external carotid artery. The larynx (Fig. 8.13) and the trachea are anterior to the digestive tract in the neck, and can be accessed directly when upper parts of the system are blocked. A cricothyrotomy makes use of the easiest route of access through the cricothyroid ligament (cricovocal membrane, cricothyroid membrane) between the cricoid and thyroid cartilages of the larynx. The ligament can be palpated in the midline, and usually there are only small blood vessels, connective tissue, and skin (though occasionally, a small lobe of the thyroid gland—pyramidal lobe) overlying it. At a lower level, the airway can be accessed surgically through the anterior wall of the trachea by tracheostomy. This route of entry is complicated because large veins and part of the thyroid gland overlie this region. Parasympathetic fibers in the head are carried out of the brain as part of four cranial nerves—the oculomotor nerve [III], the facial nerve [VII], the glossopharyngeal nerve [IX], and the vagus nerve [X] (Fig. 8.14). Parasympathetic fibers in the oculomotor nerve [III], the facial nerve [VII], and the glossopharyngeal nerve [IX] destined for target tissues in the head leave these nerves, and are distributed with branches of the trigeminal nerve [V]. There are eight cervical nerves (C1 to C8): The anterior rami of C1 to C4 form the cervical plexus. The major branches from this plexus supply the strap muscles, the diaphragm (phrenic nerve), skin on the anterior and lateral parts of the neck, skin on the upper anterior thoracic wall, and skin on the inferior parts of the head (Fig. 8.15B). Normally, the soft palate, epiglottis, and soft tissue structures within the larynx act as valves to prevent food and liquid from entering lower parts of the respiratory tract (Fig. 8.16A). During normal breathing, the airway is open and air passes freely through the nasal cavities (or oral cavity), pharynx, larynx, and trachea (Fig. 8.16A). The lumen of the esophagus is normally closed because, unlike the airway, it has no skeletal support structures to hold it open. When the oral cavity is full of liquid or food, the soft palate is swung down (depressed) to close the oropharyngeal isthmus, thereby allowing manipulation of food and fluid in the oral cavity while breathing (Fig. 8.16C). When swallowing, the soft palate and parts of the larynx act as valves to ensure proper movement of food from the oral cavity into the esophagus (Fig. 8.16D). In newborns, the larynx is high in the neck and the epiglottis is above the level of the soft palate (Fig. 8.16E). Babies can therefore suckle and breathe at the same time. Liquid flows around the larynx without any danger of entering the airway. During the second year of life, the larynx descends into the low cervical position characteristic of adults. The two muscles (trapezius and sternocleidomastoid) that form part of the outer cervical collar divide the neck into anterior and posterior triangles on each side (Fig. 8.17). The boundaries of each anterior triangle are: The posterior triangle is bounded by: The cranium can be subdivided into: The mandible is not part of the cranium nor part of the facial skeleton. The anterior view of the skull includes the forehead superiorly, and, inferiorly, the orbits, the nasal region, the part of the face between the orbit and the upper jaw, the upper jaw, and the lower jaw (Fig. 8.18). The forehead consists of the frontal bone, which also forms the superior part of the rim of each orbit (Fig. 8.18). Clearly visible in the medial part of the superior rim of each orbit is the supra-orbital foramen (supra-orbital notch; Table 8.1). Table 8.1 External foramina of the skull Medially, the frontal bone projects inferiorly forming a part of the medial rim of the orbit. The body of the mandible is arbitrarily divided into two parts: Laterally, a mental foramen (Table 8.1) is visible halfway between the upper border of the alveolar part of the mandible and the lower border of the base of the mandible. Continuing past this foramen is a ridge (the oblique line) passing from the front of the ramus onto the body of the mandible. The oblique line is a point of attachment for muscles that depress the lower lip. The lateral view of the skull consists of the lateral wall of the cranium, which includes lateral portions of the calvaria and the facial skeleton, and half of the lower jaw (Fig. 8.19): In lower parts of the lateral portion of the calvaria, the frontal bone articulates with the greater wing of the sphenoid bone (Fig. 8.19), which then articulates with the parietal bone at the sphenoparietal suture, and with the anterior edge of the temporal bone at the sphenosquamous suture. A major contributor to the lower portion of the lateral wall of the cranium is the temporal bone (Fig. 8.19), which consists of several parts: The bones of the viscerocranium visible in a lateral view of the skull include the nasal, maxilla, and zygomatic bones (Fig. 8.19) as follows: Usually a small foramen (the zygomaticofacial foramen; Table 8.1) is visible on the lateral surface of the zygomatic bone. A zygomaticotemporal foramen is present on the medial deep surface of the bone. The final bony structure visible in a lateral view of the skull is the mandible. Inferiorly in the anterior part of this view, it consists of the anterior body of the mandible, a posterior ramus of the mandible, and the angle of the mandible where the inferior margin of the mandible meets the posterior margin of the ramus (Fig. 8.19). The occipital, parietal, and temporal bones are seen in the posterior view of the skull. Centrally the flat or squamous part of the occipital bone is the main structure in this view of the skull (Fig. 8.20). It articulates superiorly with the paired parietal bones at the lambdoid suture and laterally with each temporal bone at the occipitomastoid sutures. Along the lambdoid suture small islands of bone (sutural bones or wormian bones) may be observed.

Head and Neck

Conceptual overview

General description

Head

Other anatomically defined regions

Neck

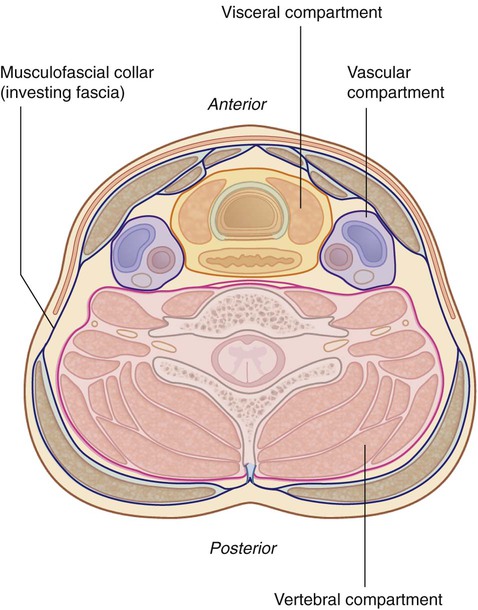

Compartments

The vertebral compartment contains the cervical vertebrae and associated postural muscles.

The vertebral compartment contains the cervical vertebrae and associated postural muscles.

The visceral compartment contains important glands (thyroid, parathyroid, and thymus), and parts of the respiratory and digestive tracts that pass between the head and thorax.

The visceral compartment contains important glands (thyroid, parathyroid, and thymus), and parts of the respiratory and digestive tracts that pass between the head and thorax.

The two vascular compartments, one on each side, contain the major blood vessels and the vagus nerve.

The two vascular compartments, one on each side, contain the major blood vessels and the vagus nerve.

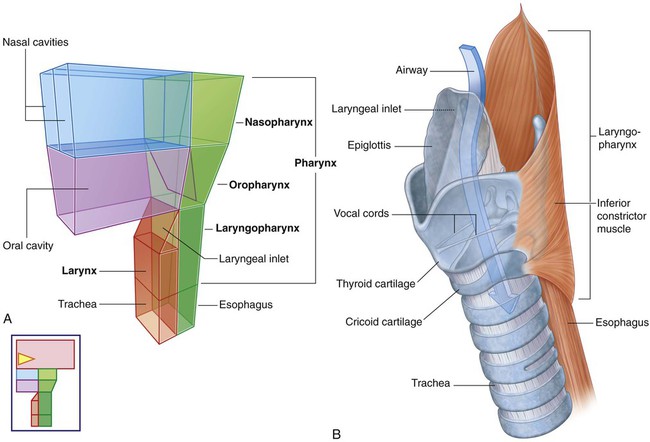

Larynx and pharynx

Component parts

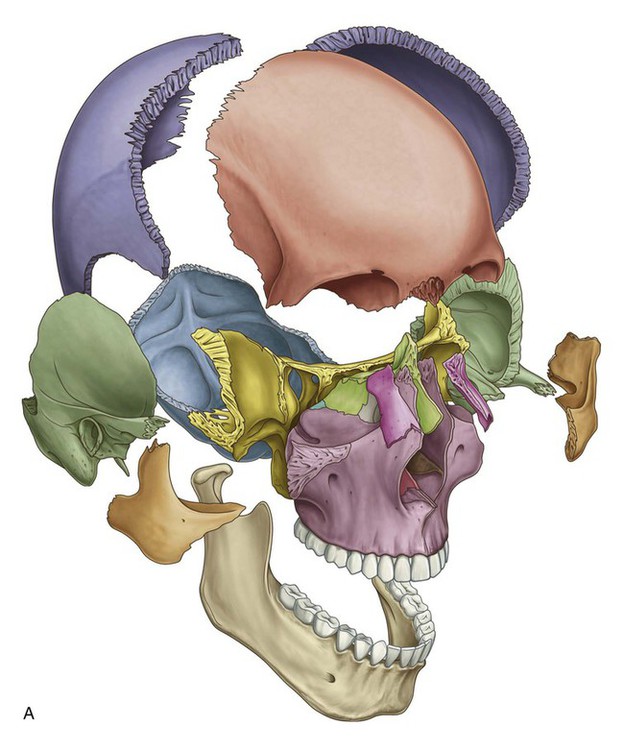

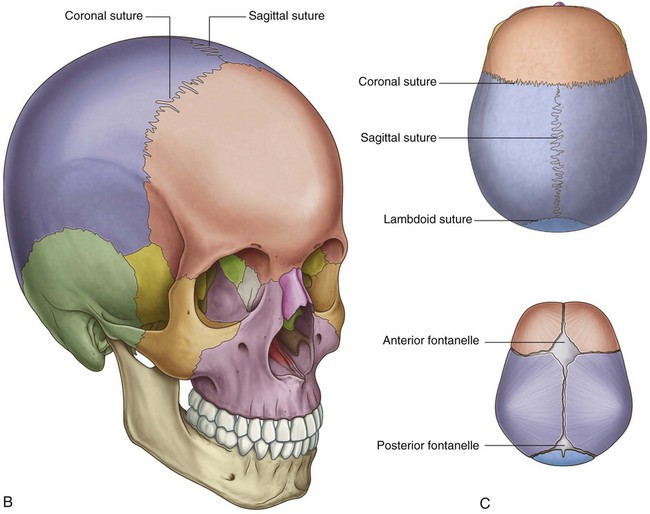

Skull

Cervical vertebrae

Hyoid bone

The body of the hyoid bone is anterior and forms the base of the U.

The body of the hyoid bone is anterior and forms the base of the U.

The two arms of the U (greater horns) project posteriorly from the lateral ends of the body.

The two arms of the U (greater horns) project posteriorly from the lateral ends of the body.

Muscles

In the head

the extra-ocular muscles (move the eyeball and open the upper eyelid),

the extra-ocular muscles (move the eyeball and open the upper eyelid),

muscles of the middle ear (adjust the movement of the middle ear bones),

muscles of the middle ear (adjust the movement of the middle ear bones),

muscles of facial expression (move the face),

muscles of facial expression (move the face),

muscles of mastication (move the jaw—temporomandibular joint),

muscles of mastication (move the jaw—temporomandibular joint),

muscles of the soft palate (elevate and depress the palate), and

muscles of the soft palate (elevate and depress the palate), and

muscles of the tongue (move and change the contour of the tongue).

muscles of the tongue (move and change the contour of the tongue).

In the neck

muscles of the pharynx (constrict and elevate the pharynx),

muscles of the pharynx (constrict and elevate the pharynx),

muscles of the larynx (adjust the dimensions of the air pathway),

muscles of the larynx (adjust the dimensions of the air pathway),

strap muscles (position the larynx and hyoid bone in the neck),

strap muscles (position the larynx and hyoid bone in the neck),

muscles of the outer cervical collar (move the head and upper limb), and

muscles of the outer cervical collar (move the head and upper limb), and

postural muscles in the muscular compartment of the neck (position the neck and head).

postural muscles in the muscular compartment of the neck (position the neck and head).

Relationship to other regions

Thorax

Key features

Vertebral levels CIII/IV and CV/VI

between CIII and CIV, at approximately the superior border of the thyroid cartilage of the larynx (which can be palpated) and where the major artery on each side of the neck (the common carotid artery) bifurcates into internal and external carotid arteries; and

between CIII and CIV, at approximately the superior border of the thyroid cartilage of the larynx (which can be palpated) and where the major artery on each side of the neck (the common carotid artery) bifurcates into internal and external carotid arteries; and

between CV and CVI, which marks the lower limit of the pharynx and larynx, and the superior limit of the trachea and esophagus—the indentation between the cricoid cartilage of the larynx and the first tracheal ring can be palpated.

between CV and CVI, which marks the lower limit of the pharynx and larynx, and the superior limit of the trachea and esophagus—the indentation between the cricoid cartilage of the larynx and the first tracheal ring can be palpated.

Airway in the neck

Cranial nerves

Cervical nerves

C1 to C7 emerge from the vertebral canal above their respective vertebrae.

C1 to C7 emerge from the vertebral canal above their respective vertebrae.

C8 emerges between vertebrae CVII and TI (Fig. 8.15A).

C8 emerges between vertebrae CVII and TI (Fig. 8.15A).

Functional separation of the digestive and respiratory passages

The lower airway can be accessed through the oral cavity by intubation.

The lower airway can be accessed through the oral cavity by intubation.

The digestive tract (esophagus) can be accessed through the nasal cavity by feeding tubes.

The digestive tract (esophagus) can be accessed through the nasal cavity by feeding tubes.

Triangles of the neck

Regional anatomy

Skull

an upper domed part (the calvaria), which covers the cranial cavity containing the brain,

an upper domed part (the calvaria), which covers the cranial cavity containing the brain,

a base that consists of the floor of the cranial cavity, and

a base that consists of the floor of the cranial cavity, and

Anterior view

Frontal bone

Foramen

Structures passing through foramen

ANTERIOR VIEW

Supra-orbital foramen

Supra-orbital nerve and vessels

Infra-orbital foramen

Infra-orbital nerve and vessels

Mental foramen

Mental nerve and vessels

LATERAL VIEW

Zygomaticofacial foramen

Zygomaticofacial nerve

SUPERIOR VIEW

Parietal foramen

Emissary veins

INFERIOR VIEW

Incisive foramen

Nasopalatine nerve; sphenopalatine vessels

Greater palatine foramen

Greater palatine nerve and vessels

Lesser palatine foramen

Lesser palatine nerves and vessels

Pterygoid canal

Pterygoid nerve and vessels

Foramen ovale

Mandibular nerve [V3]; lesser petrosal nerve

Foramen spinosum

Middle meningeal artery

Foramen lacerum

Filled with cartilage

Carotid canal

Internal carotid artery and nerve plexus

Foramen magnum

Continuation of brain and spinal cord; vertebral arteries and nerve plexuses; anterior spinal artery; posterior spinal arteries; roots of accessory nerve [XI]; meninges

Condylar canal

Emissary veins

Hypoglossal canal

Hypoglossal nerve [XII] and vessels

Jugular foramen

Internal jugular vein; inferior petrosal sinus; glossopharyngeal nerve [IX]; vagus nerve [X]; accessory nerve [XI]

Stylomastoid foramen

Facial nerve [VII]

Mandible

Lateral view

Bones forming the lateral portion of the calvaria include the frontal, parietal, occipital, sphenoid, and temporal bones.

Bones forming the lateral portion of the calvaria include the frontal, parietal, occipital, sphenoid, and temporal bones.

Bones forming the visible part of the facial skeleton include the nasal, maxilla, and zygomatic bones.

Bones forming the visible part of the facial skeleton include the nasal, maxilla, and zygomatic bones.

Lateral portion of the calvaria

Temporal bone

The squamous part has the appearance of a large flat plate, forms the anterior and superior parts of the temporal bone, contributes to the lateral wall of the cranium, and articulates anteriorly with the greater wing of the sphenoid bone at the sphenosquamous suture, and with the parietal bone superiorly at the squamous suture.

The squamous part has the appearance of a large flat plate, forms the anterior and superior parts of the temporal bone, contributes to the lateral wall of the cranium, and articulates anteriorly with the greater wing of the sphenoid bone at the sphenosquamous suture, and with the parietal bone superiorly at the squamous suture.

The zygomatic process is an anterior bony projection from the lower surface of the squamous part of the temporal bone that initially projects laterally and then curves anteriorly to articulate with the temporal process of the zygomatic bone to form the zygomatic arch.

The zygomatic process is an anterior bony projection from the lower surface of the squamous part of the temporal bone that initially projects laterally and then curves anteriorly to articulate with the temporal process of the zygomatic bone to form the zygomatic arch.

Immediately below the origin of the zygomatic process from the squamous part of the temporal bone is the tympanic part of the temporal bone, and clearly visible on the surface of this part is the external acoustic opening leading to the external acoustic meatus (ear canal).

Immediately below the origin of the zygomatic process from the squamous part of the temporal bone is the tympanic part of the temporal bone, and clearly visible on the surface of this part is the external acoustic opening leading to the external acoustic meatus (ear canal).

The petromastoid part, which is usually separated into a petrous part and a mastoid part for descriptive purposes.

The petromastoid part, which is usually separated into a petrous part and a mastoid part for descriptive purposes.

Visible part of the facial skeleton

The maxilla with its alveolar process containing teeth forming the upper jaw; anteriorly, it articulates with the nasal bone; superiorly, it contributes to the formation of the inferior and medial borders of the orbit; medially, its frontal process articulates with the frontal bone; laterally, its zygomatic process articulates with the zygomatic bone.

The maxilla with its alveolar process containing teeth forming the upper jaw; anteriorly, it articulates with the nasal bone; superiorly, it contributes to the formation of the inferior and medial borders of the orbit; medially, its frontal process articulates with the frontal bone; laterally, its zygomatic process articulates with the zygomatic bone.

The zygomatic bone, an irregularly shaped bone with a rounded lateral surface that forms the prominence of the cheek, is a visual centerpiece in this view— medially, it assists in the formation of the inferior rim of the orbit through its articulation with the zygomatic process of the maxilla; superiorly, its frontal process articulates with the zygomatic process of the frontal bone assisting in the formation of the lateral rim of the orbit; laterally, seen prominently in this view of the skull, the horizontal temporal process of the zygomatic bone projects backward to articulate with the zygomatic process of the temporal bone and so form the zygomatic arch.

The zygomatic bone, an irregularly shaped bone with a rounded lateral surface that forms the prominence of the cheek, is a visual centerpiece in this view— medially, it assists in the formation of the inferior rim of the orbit through its articulation with the zygomatic process of the maxilla; superiorly, its frontal process articulates with the zygomatic process of the frontal bone assisting in the formation of the lateral rim of the orbit; laterally, seen prominently in this view of the skull, the horizontal temporal process of the zygomatic bone projects backward to articulate with the zygomatic process of the temporal bone and so form the zygomatic arch.

Mandible

Posterior view

Occipital bone

Head and Neck